Change initiatives are often launched with great fanfare. The CEO joins an earnings call and speaks passionately about how the effort will enable the organization to explore emerging frontiers or reimagine the way it does business. Top management rallies around the new vision of the future. But the excitement starts to dwindle as the news travels down the hierarchy. By the time it reaches the company’s rank-and-file workers in a town hall or email, it lands with a thud—generating apathy and anxiety. It’s no wonder that roughly 75% of change efforts fail to capture long-term value.

People closer to the decision making feel more favorably toward change than those further away.

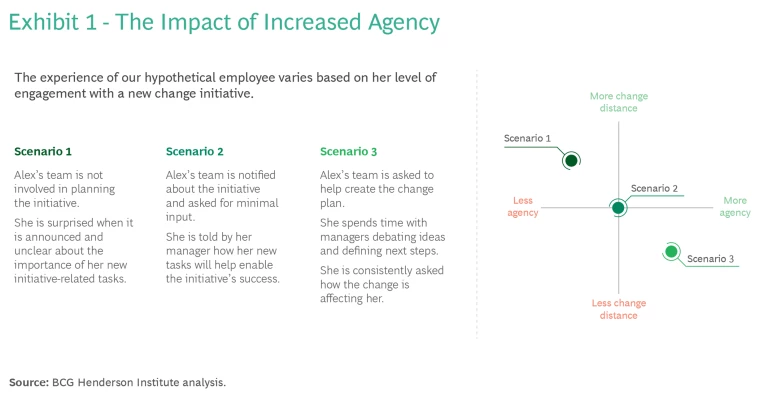

This scenario reveals a critical phenomenon that can be observed in many organizations. We call it “change distance”: People closer to the decision making (often senior leaders) feel more favorably toward change than those further away (often rank-and-file employees). This finding builds on our research on change aversion—the idea that people inherently view change as negative, and that emotion overwhelms their ability to consider the potential benefits of change. The more space that exists between people and the initiative’s center of gravity, the more pronounced this effect becomes.

Change distance is a powerful force, and likely underlies many failed transformations. It is also logical: Change initiatives originate at the top, where CEOs brainstorm with their closest lieutenants, weigh options, create a roadmap, and give the green light for implementation. Because they are deeply engaged with decisions from the start, this group has less change distance. They’ve bought in. In contrast, a lower-level employee might only receive that companywide email where everything feels set in stone. Without agency, they experience more change distance—and their aversion starts to rise. (See Exhibit 1.)

The Drivers of Change Distance

We’ve identified a number of factors that contribute to change distance in organizations. Some reflect roles and business trends; others result from troubling disconnects between leaders and the people they lead.

Leaders have built a tolerance to change. During their climb up the corporate leader, leaders are exposed to multiple change initiatives. Over time, such exposure often “numbs” leaders into developing the ability to maintain a steady state. We can liken this to a psychological form of hedonic adaptation: To maintain a constant level of happiness, people subconsciously accept that both good and bad things will happen, limiting the impact of these events on their emotional well-being. It’s all just “normal life.” For leaders, change is normal life—and it becomes more and more normal the farther up the ladder they’ve climbed.

A selection effect influences leaders. Leaders aren’t just tolerant of change; they see it as a way to advance their careers. As they look to rise through the ranks, leaders often find that the fastest path is to pursue roles that involve leading change programs. This selection effect is compounded as individuals are rewarded when the changes they manage are successful. In our research, we’ve found time and again that leaders at the highest levels of organizations are the most bullish toward change programs—and that they often point to their past oversight of such programs as a core component of their professional success.

Change is the currency of leadership. Among the top 10 performing companies in the S&P 500 in the first half of 2023, five announced significant changes (such as a large repurchase program, an introduction of a next-generation AI product, and so on) in the last three months, either in their corporate announcements or quarterly earnings reports. These companies’ stock prices soared more than 45% in the last ~12 months on average, yet their leadership still seeks to pursue additional changes. Leaders aren’t complacent and neither are the contextual forces at play: shareholders’ expectations, the pursuit of competitive advantage, executive compensation packages that contain incentives to be bolder, bigger, and different than before. Leaders are playing to their audience.

Deciding and doing are very different experiences. Leaders are the decision makers, but the implementers are the ones whose routines are being disrupted and who are being asked to take on new tasks. We’ve found that this phenomenon can cause an empathy gap between leaders and employees. When we hear leaders make comments like “it is not that complicated,” this is a sure warning sign for failed change.

Leaders don’t try to understand why some people resist change. Leaders acknowledge that some people within their organizations are change resistors. However, they often consider them all together as a group of hard-stuck naysayers that need to be persuaded or otherwise dealt with to move initiatives forward.

The reality is much more nuanced. Some employees are true conscientious objectors to change; they are not simply expressing aversion to change, but instead are thoughtfully opposed to some or all of the change agenda. They express their objection through resistance, likely because speaking up in the workplace is difficult: In fact, researchers Frances Milliken, Elizabeth Morrison, and Patricia Hewlin found that more than 50% of employees will not voice their opinions at work, especially on a contested issue.

Four Steps to Build Employee Agency

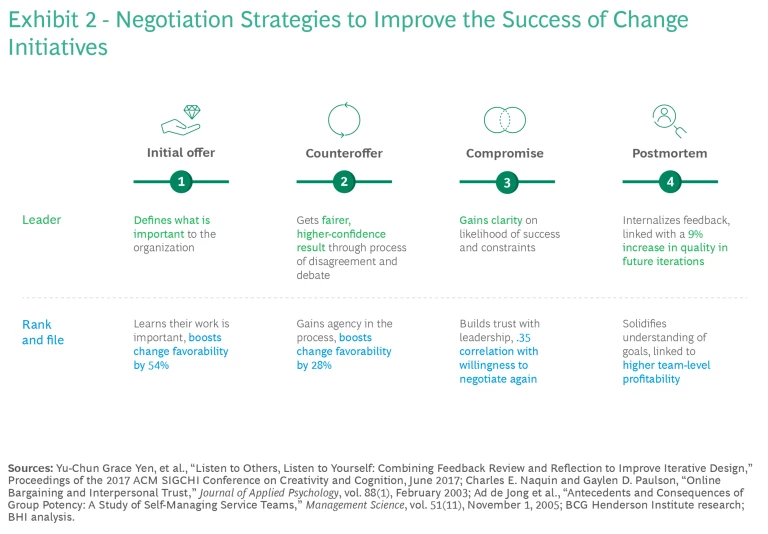

In our work, we’ve found that leaders can mitigate the effects of change distance if they actively increase employee agency. Using negotiation techniques as a framework can help. (See Exhibit 2.)

Step 1: The Initial Offer. Negotiation strategy teaches us that we need to state our intentions up front, so that both parties have a clear understanding of the “what.” But leaders often fail at communicating, in straightforward terms, what the change is, why it’s important to the organization, and how employees will contribute. Simply saying, “Our company will be better off in the future” is not enough to inspire employees.

We found that when employees were explicitly told why their role in a change initiative is important to the company, they were 54% more likely to support the change. Agency is built through recognition of the value one brings, and when leaders articulate that value to employees at the earliest stages of a change program, they establish a foundation that increases the likelihood of success.

Step 2: The Counteroffer. It is important in negotiation to consider the must-have items as well as the context of what the counterparty has to offer—both parties want something, and the initial offer rarely concludes the negotiation.

During transformations, initiative-related tasks are typically added to employees’ current workload. Listen to lower-level employees and try to understand their wants, needs, and frustrations. Use this counteroffer and subsequent negotiating time to assess what can reasonably be added, but also to consider what can be subtracted from their daily work to make room for new, critical tasks. Engaging in this back-and-forth allows leaders and employees to clarify what is most important to them and to advocate for these things. This process builds agency by giving employees direct input on outcomes.

The bargaining process and the pain of disagreement are critical. UC Berkeley psychology professor Charlan Nemeth found that jury verdicts were considered significantly more just and that jurors felt more confident in their verdicts when one or more of the jurors did not agree with the majority at the start of deliberations.

Step 3: The Compromise. Although leaders of organizations are in a position of power, they must understand that the outcome of a negotiation tends to move both parties toward a compromise. In some cases, the counterparty may not be able to provide what you want. This learning is important, given that most change initiatives fail. By understanding what will not work, leaders and employees can refine strategies to make them more likely to succeed or decide that a change is not worth pursuing. Think of this “failed negotiation” like preventative care that obviates the need for serious medical intervention.

The trust built between parties through negotiation and mutual understanding is also valuable irrespective of negotiated outcomes. In fact, researchers Charles E. Naquin and Gaylen D. Paulson found that satisfaction with an outcome has no measured effect on willingness to work with the same counterparties in the future; however, mutual respect and trust have a significant positive impact on this willingness. This is important to consider for both future transformations and employee retention. Employees who feel heard and have a better understanding of company management are more likely to stay put.

When employees are treated as thought partners, change enablers, and as the initial customers of the idea, it boosts their buy-in and improves the chances of an initiative’s success.

Step 4: Postmortem and Reflection. Whether the parties reach a compromise or scrap an initiative, it is important for leaders to gather feedback from their counterparties and reflect on what they learned during their negotiation. Research supports the need for this step. For example, researcher Yu-Chun Grace Yen and her colleagues found that in iterative design projects, designers who routinely received feedback and then reflected on their project were consistently rated by experts roughly 10% more positively on future projects.

Leaders of change initiatives should consider: What did your employees tell you was important to them? What were your employees happy with or dissatisfied with?

By acknowledging feedback, leaders can learn about their company culture, develop new initiatives better suited for success, and design job listings that speak to prospective employees and address company needs.

Leaders often say, “our people are our greatest asset,” yet when it comes to transformation, these same people are often ignored. But when employees are perceived—and treated—as thought partners, change enablers, and as the initial customers of the idea, it boosts their buy-in and improves the chances of an initiative’s success. Change distance may be powerful, but agency is an even greater force.

The authors thank Philip Jameson for his help finalizing this article.