Meet Ashley, a single mom with four children ages 3, 5, 8, and 10, who works at a manufacturing plant in the Midwest. Each weekday morning at 5:30 a.m., Ashley awakens her two oldest children to watch their younger siblings. She then heads to work for an 11-hour shift that begins at 6 a.m. and ends at 5 p.m. After working on the line for two hours, she slips out at 8 a.m., risking her job, so she can drive her two oldest children to school, her 5-year-old to pre-K, and her youngest child to a full-day childcare center. When pre-K and the childcare center let out at 3 p.m., she uses a combination of family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) care and “sibling care” until her shift finishes. That often means leaving her children alone for two or three hours.

Ashley is not an outlier. Her story demonstrates the hoops through which millions of working parents and other caregivers must jump. About 15.4 million children below age 6—representing 62% of the US population of children that age—are placed in some type of non-parental childcare. This number is expected to grow as labor-market participation increases in high-demand female-led industries, such as health care and educational services. The challenges of finding childcare are well documented: care is generally too expensive for many families, is offered at times and in locations that are inconvenient or inaccessible, and is staffed with childcare providers who are underpaid.

About 62% of US children below age 6 are placed in some type of non-parental childcare.

Every caregiver in the United States must weave together a different patchwork of solutions often based on family-specific factors, such as geography, income, the number and ages of their children, along with the availability of grandparents, other relatives, and neighbors. Workplace dynamics also play a major role. Industries like health care, retail trade, or manufacturing—which often require people to be present at specified times—place more constraints on caregiver decisions. Furthermore, with new ways of working emerging in a world influenced by COVID-19, harmonization of the workplace and childcare is critical to meet the needs of families and employers.

The result is a childcare supply shortage verging on crisis that impacts the US economy, employees with caregiver responsibilities, their employers, their schools and communities, the people who provide childcare, and, most important, the children. As the Bipartisan Policy Center noted in a comprehensive 2023 report, “Despite wide acknowledgment of the importance of high-quality care and learning opportunities for young children…available resources still fall far short of the need.”

Solving this crisis requires appropriate investment in the supply side of childcare from multiple sources: federal, state, and local governments; philanthropies and nonprofits; and the private sector. It also requires consensus around standards to ensure that high-quality solutions are propagated and scaled. In addition, players within the childcare ecosystem must coordinate to develop innovative and agile solutions, such as employer subsidies, onsite care, and extended hours, to meet the needs of working families.

Only with improvements in all these areas can working caregivers, children, and the broader US economy thrive. Fortunately, there are ways to encourage collaboration and coordination, and to reconfigure the childcare industry in a way that better serves caregivers and, in turn, employers.

To understand the dynamics of the industry and articulate a way forward, BCG surveyed more than 2,500 working caregivers with children below age 5 in March 2023. We asked them, “What would it look like if the childcare system was built in a way that felt customized to your needs?” They revealed their preferences across core aspects of childcare, including type of care, location, and hours.

The recommendations detailed in this report are based on the results of this in-depth survey, reflecting the needs, experiences, and observations of working parents and other caregivers. Our goal is for this research to serve as an input into conversations around transforming childcare, empowering key stakeholders, including state- and local-level policymakers and employers, to develop a childcare ecosystem that is built around their population’s specific needs.

Childcare Matters Across All Industries

Studies by the US Census Bureau and the US Bureau of Labor Statistics have found that 5.5 million caregivers report being underemployed because of childcare constraints. This is a drain on their current income and long-term career prospects. Meanwhile, across industries, employers are challenged to recruit quality staff members. In many situations, affordable childcare can help solve both problems at once.

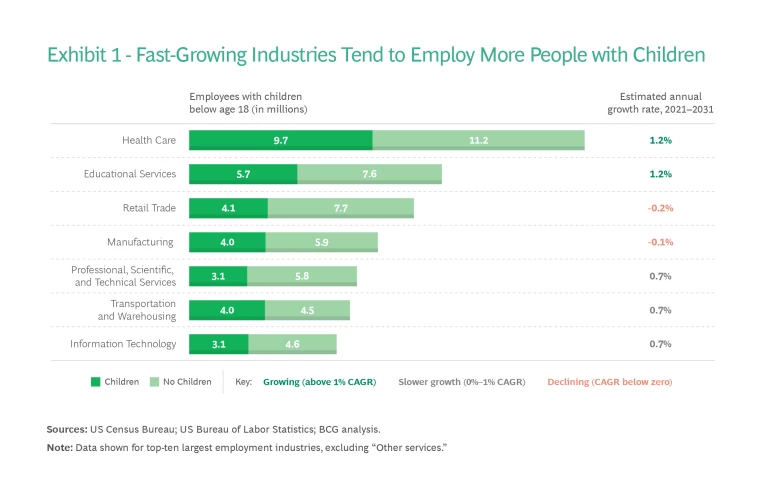

Childcare matters across all industries, but is particularly relevant to the seven industries with the largest number of employees––health care, educational services, retail trade, manufacturing, transportation and warehousing, information technology (IT), and construction. Together, they employ 79.8 million people. Workers in these industries, except for IT, tend to be “deskless workers”; they have limited options for remote work, are typically required to be present in person, and include a larger proportion of lower-paid workers.

Notably, the two fastest-growing industries, health care and educational services, predominantly employ women: 73% and 69%, respectively. They tend to have the highest share of employees seeking childcare, as more than half of their combined 30 million employees have children below age 18 (see Exhibit 1).

The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the childcare crisis and demonstrated to industry leaders the stresses that finding reliable childcare placed on the workforce, especially for deskless workers who could not complete their work from home. This lack of childcare led to employee shortages across industries, including health care and educational services. The pandemic also accelerated innovation in work design, forcing many families to change their routines and, in turn, creating the need for more flexible childcare. Now, with many workplaces gravitating toward a “new normal,” additional childcare providers and innovative childcare solutions are needed more than ever. These solutions should be designed to meet the varying preferences and constraints of caregivers in the largest US industries.

Childcare Supply and Childcare Deserts

The spectrum of childcare options can be divided into three categories that differ in terms of flexibility and formality:

- Formal care (center based) – group childcare, or center-based care, provided in a building other than a person’s home. This category includes federally funded programs such as Early Head Start and Head Start; state and locally funded pre-kindergarten (pre-K) programs; and privately funded care such as daycare centers, nursery schools, faith-based childcare, and preschools.

- Informal care (home based) – small-group or individual care taking place in private homes. This category includes in-home daycare (sometimes known as family childcare), where childcare providers stay in their homes and charge a fee. That might mean one adult hosting a few non-related children during the workday. This category also includes au pair or nanny care, where the caregiver comes to the child’s home each day.

- “No fee” care – also known as family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) care, this category involves individual or sibling care provided at home without explicit fees, by a family member, friend, or neighbor. For example, a grandmother might care daily for her grandchildren. Parental care, where full-time care is provided by a parent or legal guardian, is also included in this category.

Throughout the US, all three categories are stressed by lack of supply. According to current US census data, 51% of Americans live in a “childcare desert.” These are census tracts with more than 50 children below age 5 (out of a total population under 8,000), where there are more than three times as many children as slots with licensed childcare providers. These deserts are disproportionally located in low-income urban and rural communities, and many of these communities have no licensed childcare. Caregivers who find suitable childcare providers are often then confronted with years-long waiting lists that may require sign-up before a child is even born.

One caregiver we spoke with, a schoolteacher from rural West Virginia, stated that there are no licensed childcare providers within 50 miles. The family utilizes FFN care, relying on the child’s retired grandmother and aunt for consistent childcare. “We do not know what we would do if family was not around,” he says. “There is no alternative or safe place to take our daughter during the day.”

70% of caregivers—regardless of industry, job type, geography, or income—are unhappy with their current childcare situation.

The survey found that 70% of caregivers—regardless of industry, job type, geography, or income—are unhappy with their current childcare situation. This dissatisfaction is greater for workers living in rural areas and for those employed in several of the largest industries: health care, manufacturing, construction, and transportation and warehousing.

The cost of care further exacerbates the supply problem. Regardless of their income levels, American families pay, on average, more than $10,000 per year for childcare for each child below age 6. About 2.9 million households pay childcare costs greater than 20% of their annual household income.

“There’s a childcare provider around the corner from me,” says a health care worker who lives in a suburb near a major city, “but it’s $1,300 a month for one kid, and I have three. When I saw that, I had to ask myself, ‘Why am I even working?’ My salary can barely cover that cost.”

What Caregivers Want

When asked about their ideal options, 75% of survey respondents ranked “parental care” as the most preferred option for childcare. This sentiment is even stronger in some industries, such as health care, educational services, retail trade, manufacturing, and transportation and warehousing. However, like Ashley, most respondents recognize that parental care is not feasible for them.

The second most preferred option—across all major industries, geographies, and income levels—is formal care, utilizing licensed childcare providers. However, when considering gaps in supply and additional types of care that should be built, preferences vary across industries. Health care and IT employees want more home-based care options, while construction and manufacturing workers want more formal center-based care options. Many caregivers, regardless of industry, want to reduce their reliance on FFN care, shifting to more formal paid options. Furthermore, educational services and retail trade employees tend to want more of all types of care. There is an opportunity to build childcare supply based on industry-specific needs.

Only 29% of caregivers surveyed had childcare available for all the hours they needed to spend at work.

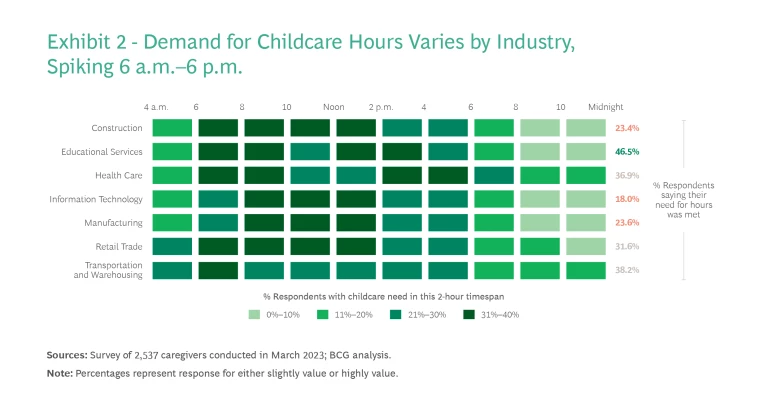

Another critical pain point relates to the time childcare is available. Only 29% of caregivers surveyed had childcare available for all the hours they needed. In industries such as IT, construction, and manufacturing, that percentage was below 25%. As shown in Exhibit 2, the hours in demand spike between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., but can vary by industry. For instance, transportation and warehousing workers often require care starting at 4 a.m., while health care workers require childcare up until 8 p.m. Across the board, the ideal time for childcare generally starts at 6 a.m., but many providers do not open until 7 a.m. or 8 a.m. Caregivers must therefore find supplemental forms of care, including family members or even siblings, as noted in Ashley’s story. Some caregivers are forced to reduce their own working hours.

Employees with caregiving responsibilities also express strong preferences when it comes to the location of care. When asked to define the ideal situation, caregivers want childcare providers very close to home (37%) or at home (28%), with at-home preferences higher for children below age 2. Manufacturing caregivers broke with this trend, as 30% prefer a location on their commuting route, between home and work. Only 7% of caregivers surveyed report a location preference of care very close to work, and 2% cite a preference for care at work.

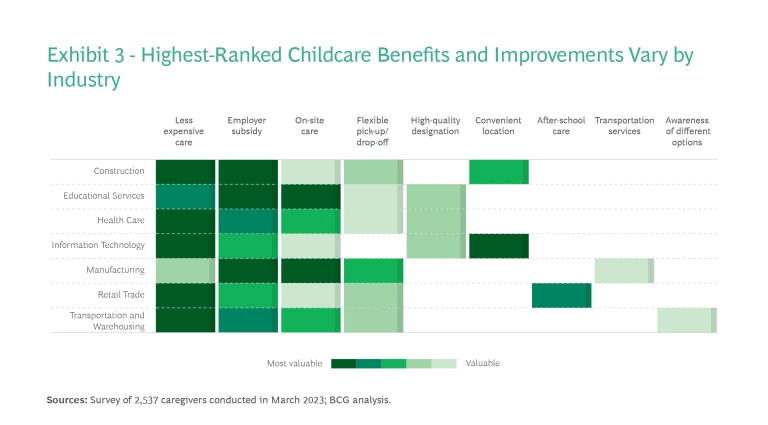

When asked about benefits and add-ons that would most improve their current childcare situation, caregivers, regardless of industry, cite a reduction in cost. Financial-related benefits, such as a direct childcare subsidy or support for less expensive site-based care, would be the most valuable improvements to caregivers’ current situation.

Notably, while relatively few caregivers say they would independently prefer childcare sites located near work, most are open to onsite care established by employers at the workplace itself. Manufacturing and educational services employees rate this as their highest-valued benefit, while employees of health care and transportation and warehousing organizations place it among their top three. The advantage is that employers can often reduce the cost of onsite childcare and align care with the hours employees are at work.

As shown in Exhibit 3, additional preferred benefits tend to vary by industry. Construction and IT workers want childcare providers that are in more convenient locations, such as highly trafficked areas. Manufacturing, construction, retail trade, and transportation and warehousing employees value care that better accommodates their schedules, with flexible pick-up and drop-off options. Furthermore, educational services, health care, and IT workers emphasize the need for designated high-quality childcare providers.

Given these differences, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for childcare. It is critical to pay attention to the differences in caregiver experiences, look for gaps in care specific to each industry, and develop customized solutions that better meet those employees’ needs.

On a broader scale, the childcare crisis can only be addressed if all stakeholders come together to adopt a multi-pronged approach to building and expanding supply. This includes employers, city planners and developers, childcare operators, school districts, faith-based organizations, philanthropies and nonprofits, and state and local government officials.

Stakeholders with a Central Role

While everyone can play a role, five actors are central to building the childcare ecosystem. State and local governments, employers, city planners and developers, childcare operators, and philanthropies and nonprofits can all take steps toward improvement.

State and Local Governments

Policymakers and government officials have a unique opportunity to build out the supply side of the childcare ecosystem by providing public funding, developing supportive policies, and coordinating across agencies. While Biden recently signed executive actions aimed at expanded federal funding for childcare and pre-K, there are also some things that can happen closer to home. The actions of state and local government officials can catalyze other stakeholders, accelerating and broadening their impact.

At the state level, policymakers have many ways to improve the affordability, availability, and quality of childcare. All states should support the building of additional childcare programs. As state governments put together their childcare plans, they should better understand their workforce landscape to make the most of their resources. The first step is to assess the current childcare ecosystem—population dynamics, predominant industries, workforce trends, and other factors that affect childcare; then develop and implement an array of solutions and incentives tailored to their unique situation.

Using this tailored approach will result in solutions that differ among states. For example, Michigan has 10 million residents, with 25.4% living in rural areas and 44% in childcare deserts. It has a high percentage of its workforce (14.2%) in the manufacturing sector. This suggests the need for policies that encourage employers to develop onsite care facilities and provide subsidies for flexible and extended hour childcare. These policies would help alleviate the last-minute schedule changes that are typical of the manufacturing sector, which would be highly valuable in Michigan.

Washington State, by comparison, has 7.8 million residents with 16% living in rural areas, and a much larger percentage (63%) living in childcare deserts. It has relatively few manufacturing employees, but 8.7% of its workforce is in IT and 7.3% in construction. The state government could help incentivize the construction of childcare centers near high-population areas, given the high percentage of childcare deserts there. Moreover, to cater to the health care and IT sectors, Washington State could incentivize and support the growth of home-based care options.

All 50 states have two imperatives in common: build infrastructure and support collaboration.

The specifics may vary, but all 50 states have two imperatives in common. They need to build the infrastructure to create childcare opportunities, and they need to support collaboration among the diverse stakeholders who can take part in expanding and improving childcare in their states.

Furthermore, local government officials can support land-use policies that streamline building approvals for childcare facilities and incentivize new programs via tax credits. They can also use their relationships with other policymakers to advocate for policies that promote childcare.

Employers

Employer subsidies are ranked the number one childcare benefit by construction, educational services, and manufacturing employees. Health care, retail trade, transportation and warehousing, and IT workers all chose “less expensive care” as the number one benefit, with employer subsidy as a top-three benefit. This finding shows that, regardless of industry, employer subsidies are highly valued.

“An employer subsidy would greatly improve my childcare situation,” says one caregiver working in educational services. “My family does not qualify for state vouchers, but we also do not make enough money to afford childcare. An employer subsidy would allow my family to afford childcare and also increase my commitment to my employer.”

An employer subsidy would allow my family to afford childcare and also increase my commitment to my employer.

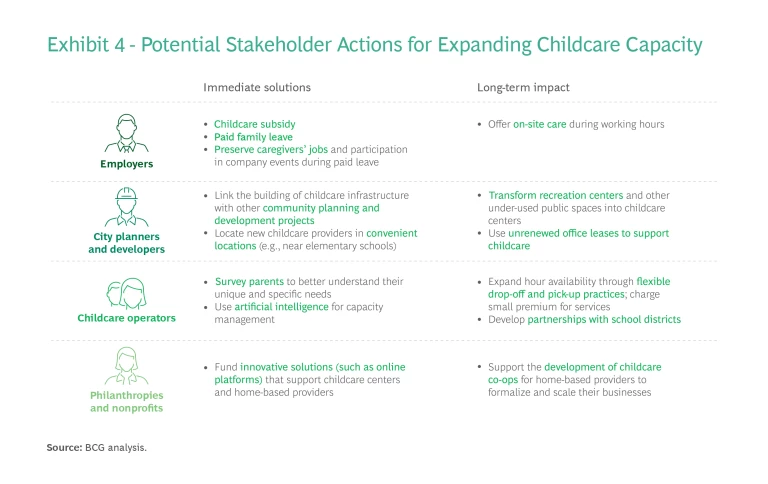

Beyond subsidizing childcare, employers can improve supports for caregivers in a variety of ways. They can add paid family leave, so employees with caregiver responsibilities can focus on parental care—the most highly prized form of childcare, especially when children are below age 1. Employers can maintain caregivers’ employee status during this period, allowing them to participate in company events to keep them located in the community and invested in the company. Additionally, as previously stated, employers can offer onsite care programs aligned to caregivers’ working hours. One viable path to offering a high-quality program is for employers to provide the space, and then partner with a childcare provider to build and operate the program.

City planners and developers

The design of a community—including its open space and zoning restrictions—can foster more and better childcare options. To create this community and link the building of childcare locations with other community development projects or facilities, city planners and developers can take a leading role. First and foremost, they need to support building up quality supply. They can do this by rezoning or adapting high-density neighborhoods so that additional childcare providers will grow there. As noted, more convenient childcare locations would be especially valuable to communities with a high number of construction and IT workers.

Furthermore, they can transform recreation centers into places where home-based and FFN providers can take children during the day. This is especially advantageous for health care and IT workers who want more home-based care options. It also allows more children to play together, and will help develop a larger ecosystem of care, one that enables childcare providers to learn from one another and leverage additional resources and supports.

Childcare operators

It is critical for childcare providers to better understand caregivers’ needs. Given the disparity between the hours caregivers need care and the hours care is offered, operators can conduct a caregiver survey, asking specifically about the hours where care is needed. Based on the survey responses, and if possible, operators can look to align their hours to the times when childcare is most needed.

Additionally, operators should look for ways to accommodate schedule changes by providing flexible drop-off and pick-up options, or one additional hour of care either in the morning or evening. This might involve a caregiver premium or an opt-in after-hours service shared with other childcare providers. Communities with a larger number of manufacturing, construction, retail trade, and transportation and warehousing workers would most benefit from this optionality.

These changes may be difficult, given employee shortages at childcare operators, and will likely require additional investments to attract enough educators to allow operators to expand their hours.

Philanthropies and nonprofits

Philanthropies and nonprofits have an opportunity to help build childcare supply by funding innovative solutions that support both formal childcare providers and home-based providers. These solutions might include shared services platforms that streamline and consolidate support functions, and thereby allow childcare providers to focus solely on what matters most: high-quality care. They can also support the development of childcare co-ops, enabling home-based providers to formalize and scale their businesses.

One Key Action Item for Each Stakeholder

One Key Action Item for Each Stakeholder

City planners and developers – link the building of childcare infrastructure with other community development projects.

Childcare operators – survey parents to better understand unique and specific childcare needs.

Philanthropies and nonprofits – fund innovative solutions (such as online platforms).

Exhibit 4 shows some of the potential contributions that non-government stakeholder groups can make.

A Call to Action

Most stakeholders are aware of the need for better childcare. Companies are struggling to hire and retain skilled workers, and childcare is one of the largest barriers. Through this survey, caregivers have provided input on solutions that could help transform the industry in a way that meets their needs. This gives us a clearer understanding of the variety of challenges that caregivers face, the tradeoffs they are forced to make, and the opportunities that exist for stakeholder-generated solutions that are tailored to caregivers’ needs.

Funding has modestly increased as federal policies, such as the 2022 US CHIPS and Science Act, include subsidies for childcare, and some states are eager to kick-start their local economies. The stars may be finally aligning around the importance of sufficient childcare supply. It is time for stakeholders to act.

During the next few years, as solutions are implemented, it is essential for stakeholders to build supply, learn from experience, and continue to iterate. With many efforts to revamp the supply side of the childcare market, some will have unexpected impact. It is crucial to tailor approaches to the wide range of American communities and find out what works best.

The US needs an agile, innovative approach to childcare. This should include the infrastructure for sharing knowledge, where a broad base of stakeholders can listen to caregivers, compare notes with one another, test and iterate through experimentation, track the results, and scale up the ideas that work. With this vision and with each stakeholder doing their part to make this system a reality, we could soon have a high-quality childcare system that is affordable, accessible, and flexible—one that not only meets the needs of caregivers, but also does its part to solve the workforce crisis.