CEOs need to identify new sources of value creation, one of which has been hiding in plain sight: the value that comes from changes in the supply and demand of capital, goods, and services. Most companies don’t know how to extract that value, and these opportunity losses add up.

Imagine a steel manufacturer that neglects to benefit from short-term price hikes by reselling already-procured power. Or a semiconductor manufacturer that fails to redirect production to serve an industry in which a competitor is struggling to meet demand. In such cases, traditional companies can neither reorient and fully optimize their complex supply chains amid changing market prices nor react swiftly to external shocks. This leaves money on the table.

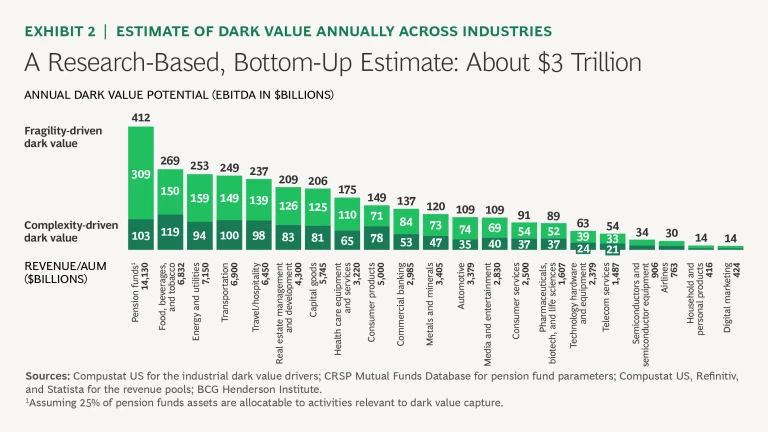

We refer to this cumulative opportunity for industrial companies as “dark value,” because, as with dark matter in physics, we can see the effects of this value (in trading profits and lost opportunities) but can’t measure it directly. But by analyzing these effects, we’ve quantified the value across multiple industries. A handful of industries are already adept at capturing dark value, but most are still in early stages or have yet to start. Companies in these industries are missing out on $10 billion to $280 billion annually. (See Exhibit 1.)

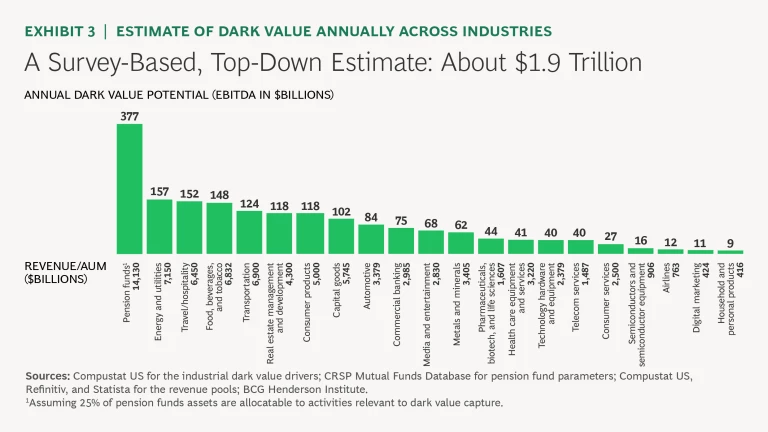

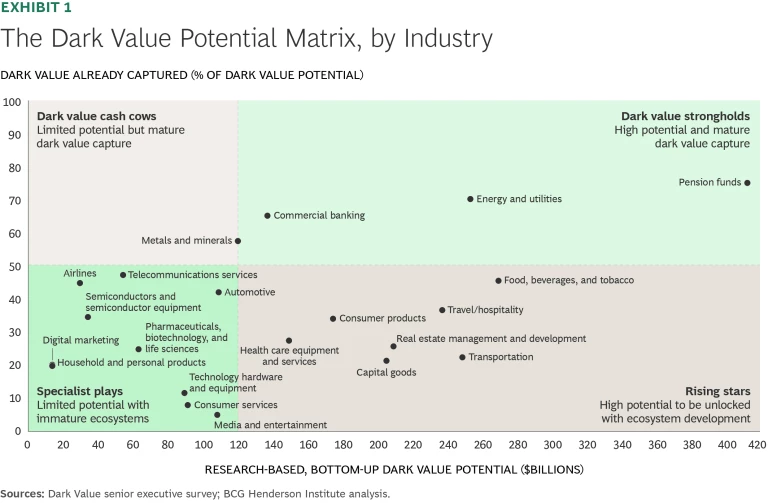

Based on our research, we believe the total pool of dark value in the economy is $3 trillion—a figure that represents 2% to 3% of global GDP. (See “Methodology.”) To complement our quantitative analysis, we surveyed approximately 500 industry C-suite executives on their perception of dark value. Our results revealed widespread belief in the existence of dark value and the upside it brings—on average, a 1% to 3% of EBITDA uplift from trading and commercial management. This is well in line with our estimates of the potential dark value left per industry.

Exhibits 2 and 3, respectively, show our research-based, bottom-up projections and our survey-based, top-down projections.

Why Dark Value Is Having a Moment

We believe that part—about $1.2 trillion—of the total pool of dark value is already being captured by dark value “specialists” such as traders and hedge funds. This makes sense when we expand the definition: dark value materializes in arbitrage, when prices diverge enough to create low-risk trades, and through volatility, which creates value for real option holders or those with the ability to carry risk when the reward for carrying it is high.

But there’s no reason why companies cannot compete for that $1.2 trillion. Further, our analysis also reveals that about $1.8 trillion is up for grabs. By quantifying dark value and gleaning insights from industries that have been able to successfully tap into it, we’re peeling back the curtain at a critical moment. As market data gets more transparent, pricing data more readily available, IT systems more proficient, and marketplaces increasingly easy to set up, the barrier to entry for dark value extraction is lower than ever. The competition will be fierce.

The barrier to entry for dark value extraction is lower than ever. The competition will be fierce.

Moreover, traditional industries won’t be competing just with specialists. Although they may not realize it, some digital-native players have already identified pockets of dark value. For example, aggregation platforms such as Booking.com bring transparency to a complex and geographically diverse mix of hotels and facilitate risk taking by buying parts of hotel room inventory for reselling purposes. These platforms release dark value by connecting buyers and sellers (lowering search cost), provide pricing transparency on equal terms, and act as a security measure against fraudulent behavior.

Over time, these platforms will direct a portion of total pool of dark value to consumers, but shocks and uncertainties are expected to increase the size of that pool.

BCG Henderson Institute: Discover new thinking shaping the business landscape

The Origins of Dark Value

Dark value remains underexploited in industries that have complex and fragile trading environments. These two core characteristics each encompasses a set of drivers that contribute to dark value creation.

Complexity Drives Pricing Inefficiencies and Arbitrage

Here are the three drivers of complexity.

Fragility Drives Volatility and the Need for Cushioning

Trading opportunities emerge following large shocks to industry supply and demand balance. An important driver of dark value is the frequency of shocks that affect prices, producers’ finances, and inventories. How much these shocks lead to trading opportunities that are not quickly arbitraged away depends on industry’s ability to heal from the shocks—that is, its fragility.

Assessing the Archetypes Across Industries

By considering the interplay of complexity and fragility, we can assess opportunity across industries, as shown in Exhibit 1.

Dark Value Strongholds

Certain industries—such as oil and gas, electricity, and financial markets—have so much dark value that, since the 1980s, specialists have traded in these opportunities. By managing complexity, risk, and capital, these specialists (hedge funds and merchant traders) have captured large amounts of dark value where industrial players would have left the value on the table; in oil, upwards of $70 billion of profits per year; in finance, up to $400 billion. What’s more, these traders have the tools not only to capture most of the remaining dark value but to keep finding new sources of dark value.

Not all industrial players have stood still, however. Many oil and gas companies have set up trading units to go after the same dark value as traders. Players in this quadrant should place dark value capture at the center of their value creation strategy.

Dark Value Cash Cows

Certain industries, such as metals and minerals, exhibit characteristics that make extraction of dark value simple—they have easily transactable commodities, relative bulk (low complexity in terms of characteristics and are easy to store, such as iron ore), and relatively little fragility to supply and demand changes. But given the size of these industries, they have limited pools of value to begin with.

Moreover, given the somewhat more straightforward nature of their products (for example, many metals, such as aluminum, are easy to store), a lot of the value has already been captured by industrial players. To ensure they don’t give away the existing value, players in this field should compete with the dark value specialists.

Specialist Players

Among this group, the overall size of the dark value pool is limited because businesses are simple or small. The capture rate is also small given a lack of adoption. These are often markets that operate well under normal circumstances but experience an efficiency breakdown in times of shocks.

For instance, semiconductor production works relatively well with long lead times, but during COVID, it broke down when supply and demand shock hit. In industries like this, dark value strategies could be considered as an insurance policy; that is, if companies prepare for the next shock, they can monetize the momentary opportunities that emerge (often when the sector is otherwise in a weak condition).

Rising Stars

These are industries that we believe have a large dark value opportunity but currently have limited capture activities because of a lack of suitable business models or markets in which to optimize the activities.

Take real estate management and development. It is rife with quality differences, slow-moving capital, and slow reconfigurability. But with recent innovations, we are seeing movement to capture some of the dark value through, for example, tokenization platforms and transparency websites. In this quadrant, players should consider how technology can help create value creation opportunities by finding new ways to transact and optimize.

What’s Holding C-Suite Executives Back?

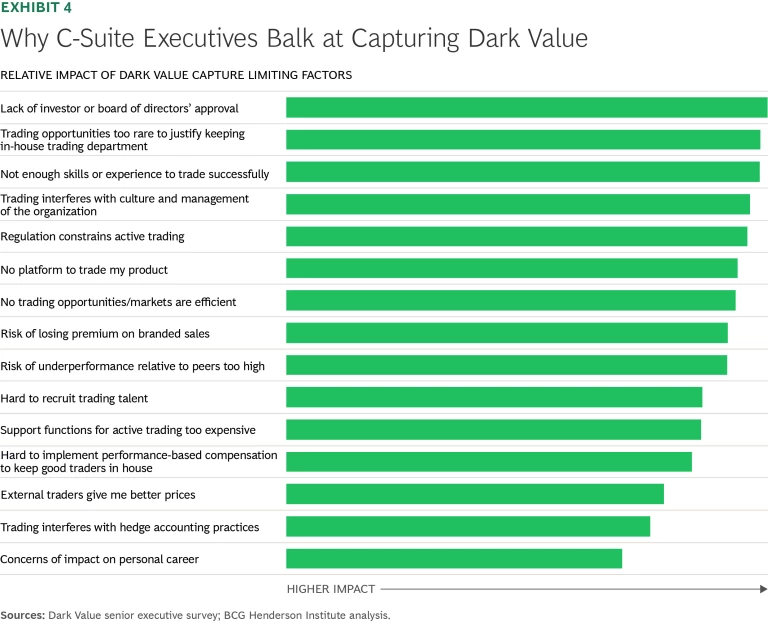

C-suite respondents to our survey noted two key obstacles. The first is the unwillingness of investors or boards to engage in trading activities; investors and boards often don’t understand trading and commercial optimization, are unwilling to engage in noncore activities, and lack the appetite for controlled risk taking. The second is the complexity and cost of the setup required to perform the activities, including the lack of and the cost of talent. (See Exhibit 4.)

These findings align closely with our experience working with company leaders. Dark value capture requires a very different skillset and a focus on, for example, incentives, organization, and risk culture. Because it depends on volatility, dark value capture is by nature difficult to predict; there are peaks and valleys in terms of the amount of value present. Management and boards are often measured on the relative performance of peers and internal KPIs, and the unpredictability of dark value activities doesn’t align with these metrics. For example, most pension funds are measured against relative performance on index, not on absolute returns (in contrast to hedge funds).

Because it depends on volatility, dark value capture is by nature difficult to predict; there are peaks and valleys in terms of the amount of value present.

However, we believe dark value capture is critical today. External shocks are increasing, leading to increased opportunities. This will expand the current $3 trillion market and open it up in a new way to participants. In many industries, ecosystem fragility is creating additional dark value, and traders are already responding. Traders are emerging in industries that don’t typically have traders, for example, generic pharmaceuticals and semiconductors.

Also, with technology speeding up ecosystem development, we are seeing more and more industries subject to dark value capture from nontraditional players. And with market data becoming more and more transparent, the ready availability of pricing data, and the relative ease of setting up new markets, the barrier to dark value extraction is lower than ever.

Technology can create completely new ways to extract dark value. For example, Dubai has launched a tokenization project for its real estate development, bringing more liquidity into the market. Another example is restaurant bookings. An individual can now resell a booking to another individual through an electronic platform; there is dark value in many people wanting to book a restaurant on short notice but not previously having had the option to express the monetary value.

Getting Started: A Roadmap for CEOs

Given the value at stake, the moves some companies and industries are already making, and the challenges others will face in entering this space, CEOs need a clear path forward. Companies that have found ways to extract dark value share some common approaches and best practices that can help others get started (including shifts in culture, processes, incentives, and mandates from the board) and can change the return distribution of the business.

The Right Tools to Monetize Dark Value Opportunities

Dark value opportunities, as described above, include complexity and fragility as components—but they are not created equal. Complexity is relatively stable, whereas fragility will depend on uncertainty in the world economy. CEOs need a toolkit that not only manages the continuous opportunities arising from complexity but also gives them the flexibility to capture value that emerges from industry fragility.

If we look at the European power-trading market, for example, we find that the complexity value (the stable component) is limited to €2 billion a year, but the fragility component drives massive dark value opportunities in times of uncertainty (up to €40 billion). (See Exhibit 5.)

Complexity management is key to sustained dark value profits: the ability to price products in different geographies, to blend different product qualities, to store products, and to acquire financing. This requires careful management of P&L at the transaction level, risk management, and sophisticated pricing and modeling of market fundamentals.

Many traditional companies employ ERP systems to maintain a strong grasp of their supply chain and costs, but most lack the market view: What is the optimal product to buy from the market to blend with mine? Should I supply some of my customers with third-party products and use my own products somewhere else? Will this product be worth more in three months than it’s valued at today?

For example, airline tickets are often “backwardated”—they cost more for short-term deliveries. Could an airline offer to buy back some tickets sold in the past and then sell them at a higher price closer to the actual flight?

Meanwhile, fragility management requires building optionality and flexibility into the supply chain. This flexibility does have a cost, and in some years will create negative cash flow, but it might pay off handsomely in other years. Many industries focus on optimizing their business two to ten years into the future and will deliver that plan accordingly, but market volatility often happens in the near term. The closer to delivery you get, the more uncertainty there actually is—making the short- to medium-term management of business extremely valuable.

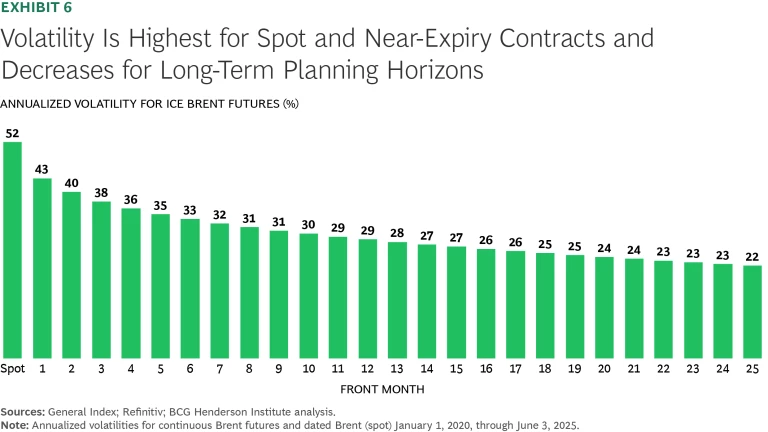

As we see in Exhibit 6, the immediate physical delivery of cargoes (spot rate) is more than twice as volatile as the price for 24 months forward from today, making optionality in the short term extremely valuable. To capture this short-term volatility, leaders must adopt a more opportunistic approach: reconfiguring the supply chain on the basis of short-term signals, securing inventories along the value chain, capturing opportunities that arise, and taking calculated and well-managed risks.

The Right Operating Model to Ensure Success

Beyond the tools themselves, CEOs need an operating model that enables their companies to capture dark value.

Classic Business Model with Dark Value Infusion. Classic business models in manufacturing or services often revolve around annual financial planning, the predictability of returns, and the fine-tuning of operational parameters. But such practices are in opposition to dark value capture principles. Most volatility in supply and demand happens in the next six months of production, with the highest volatility in the near term, creating opportunities for optimization and dark value capture. Many businesses miss this because of long planning horizons and an inability (or unwillingness) to reconfigure their supply chains.

However, some industries have found ways to infuse some dark value thinking into their strategy for their main business. For instance, in the forestry industry, some players actively engage in the optimization of the heat generation of their process by switching between a gas boiler and an electric boiler, based on the energy cost of the day. This requires active management of the industrial process, not only based on maximizing throughput but also considering the opportunity losses incurred if the company doesn’t constantly optimize. To enable this, operators and sales departments need visibility into prices and price movements as well as mandates to make changes to production and sales plans to optimize for maximum impact.

Dual Model. Oil companies and utilities have a long tradition of building specific commercial and trading units in parallel with their main business (sometimes called “markets,” “trading and shipping,” or “commercial optimization”). Some players have made this approach work well, but all face similar challenges: the ability to create and maintain a parallel culture and to pay staff healthy bonuses based on the profit and loss they create, and the creation of a separate IT infrastructure with customized solutions and a thorough risk management culture and processes. However, the recent development of lighter weight or flexible trading IT solutions has sparked discussion on this model in new industries.

These challenges often create tension between the core business and the dark value business. The former believes the latter is eating its lunch, and the latter believes the former is leaving value on the table by not being flexible enough.

Pure-Play Dark Value Model. In this model, the whole business is geared toward capturing value from complexity and fragility. This means that the whole business is constantly optimized against price signals coming from the markets. This requires a high level of transparency and well-functioning processes and mandates, as well as skilled commercial operators who can do tradeoffs in a live environment.

The incentives required are often out of reach for classical industry players, as the commercial operators often need a high share of returns to have the necessary hunger, and requirements from public listing and regulations prohibit these aggressive activities. For these reasons, most players operating with a pure-play model are privately owned physical traders and hedge funds, whose staff own the company and can manage the risk-return tradeoffs.

Dark value presents a significant opportunity across industries. In our increasingly volatile world, creating value from flexibility and reactivity will be a key tool for all CEOs. It’s well worth the challenge.

Methodology

- Our measure of industry size is the aggregated revenue (from Compustat).

- We created a dark value “index” as a function of complexity and fragility measures of the industry. This index represents our estimate of the percentage of dark value of the revenue of the industry.

- We estimated complexity and fragility using six factors (below), which we verified by regression analysis against the identified potential in our dark value survey.

- The dark value index (% of dark value of revenues), multiplied by the industry revenue, became the total dollar dark value estimate.

- To measure the percentage of dark value captured, we created an industry maturity index driven by the ecosystem maturity of each industry. This is calibrated using our industry survey and known trading profits.

The index comprises both complexity and fragility drivers.

Complexity drivers:

- Geography. Low HHI (Herfindahl–Hirschman index, which measures a company’s average market share in an industry) -> low concentration -> higher dark value potential

- Quality. High cross-sectional profit margin variability -> high quality variation -> higher dark value potential

- Time. Low inventory turnover -> more inventories to be optimized -> higher dark value

Fragility drivers:

- Reconfigurability Required. High ROIC (return on invested capital) volatility -> higher dark value potential

- Immediate Buffers. High inventory turnover volatility -> higher dark value potential

- Capital Flow. Slow capital flow -> momentum in stock returns -> higher dark value potential

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maurice Berns and Eric Boudier for their contributions to this article.