In Aesop’s fable “The Ant and the Grasshopper,” the diligent ant uses the summer to prepare for the winter ahead, while the carefree grasshopper lazes away the sunny days. When winter arrives, the grasshopper finds itself cold and hungry, while the ant thrives—sustained by its discipline and foresight.

For management teams in cyclical sectors, with large swings in cash flow over time, it can be difficult to avoid behaving like the carefree grasshopper. The environment is turbulent, so when cyclical peaks bring high earnings, easy credit, and smiles in the boardroom, people spend more aggressively. And when the cycle turns down unexpectedly (it’s so hard to time the cycle), earnings dissipate, credit tightens, and often there isn’t the capacity to do even high-return, low-risk investments. This pattern of “pro-cyclical” investing leads to the corporate equivalent of some hungry, cold, and unhappy grasshoppers.

However, one subset of high-performing cyclical companies does things differently. These high performers deliver sector-leading shareholder value over decades-long holding periods. Across the eight sectors we reviewed, the high performers showed a pattern of managing differently in three key areas.

First, they improve decision making by using a stabilized through-cycle approach—that is, they use tools and processes that “see through the cycle.” Second, they provide a financial buffer by limiting peak debt to levels sustainable with stress-case (or trough) cash flows. Third, they allocate capital consistently through the cycle, using dividends to stabilize the return of cash and using a steadier “always-on” M&A approach to conduct acquisitions.

Today, as geopolitical volatility extends to traditionally stable sectors, the disciplined strategies employed by cyclical-sector leaders offer valuable lessons for executives across all industries to build resilience and drive sustained value creation.

“Tilt” Differentiates Cyclicals: Profit Highs Equal Valuation Lows

Cyclical sectors—including oil and gas, commodity chemicals, mining and metals, agriculture, pulp and paper, and building materials—experience pronounced and recurring swings in profitability caused by inelastic supply and demand. Supply responsiveness is limited by the capital-intensive investments and lengthy lead times required to add new capacity, such as building pipelines or opening mines, while demand often remains relatively stable because of limited substitutes and high switching costs.

These structural dynamics make cyclical sectors especially vulnerable to supply disruptions or geopolitical shocks. Within a single cycle, the resulting market price movements regularly trigger EBITDA fluctuations of 50% or more from peak to trough. Such volatility introduces distinct challenges for investors and management teams.

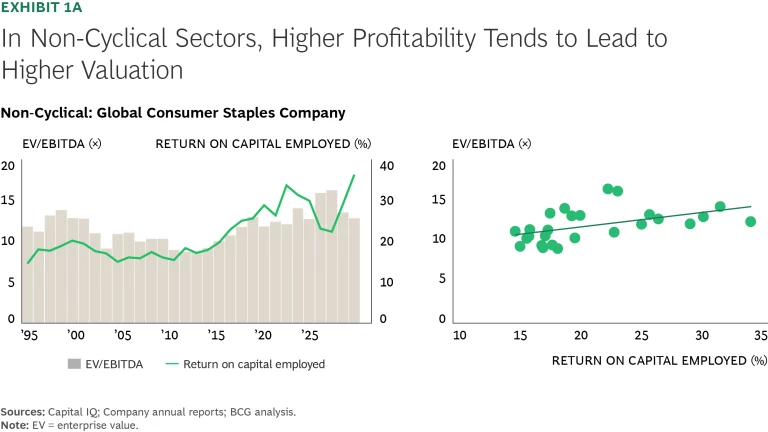

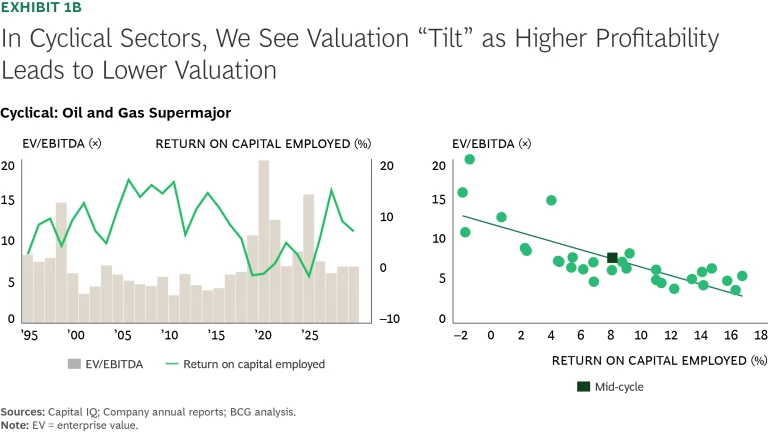

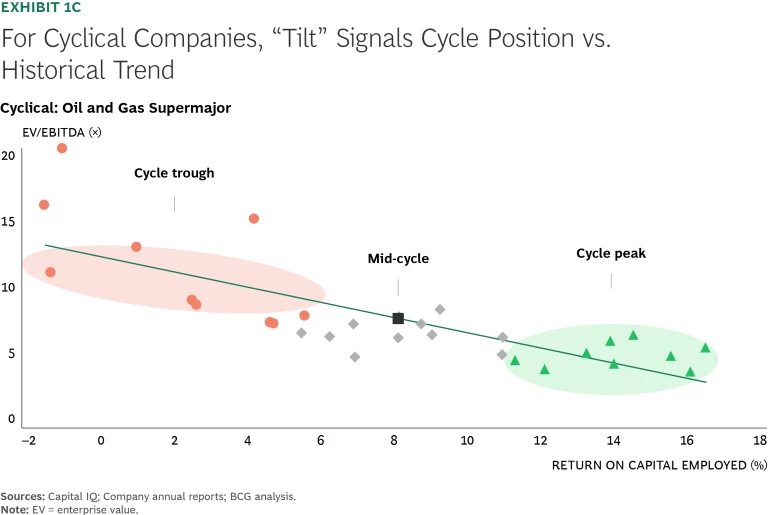

Another defining—and somewhat counterintuitive—feature of cyclical sectors is the inverse relationship between current profitability and valuation multiples, referred to as “tilt.” (See exhibits 1a, 1b, and 1c below.)

In non-cyclical sectors, higher returns typically correspond with higher valuations. Cyclical sectors exhibit the opposite phenomenon. Because investors value companies based on stabilized, through-cycle profitability rather than temporary earnings spikes or dips, valuation multiples compress during profit upswings and expand during profit downswings. This dynamic often frustrates management teams, who point to low enterprise value/EBITDA multiples during periods of peak earnings as signs of undervaluation, when in practice, owners are pricing in mean reversion.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on corporate finance and strategy

Shorter-Term Investors, Longer-Term Investments: A Strategic Mismatch

Cash flow variability poses a distinctive challenge for management teams in cyclical sectors, especially when current performance deviates significantly from mid-cycle norms. These pronounced financial swings from bullish to bearish extremes can be disorienting for leadership teams, making it hard to adopt disciplined through-cycle behavior.

Compounding this challenge is a fundamental disconnect between management and investors. A recent BCG survey of 150 investors who focus on cyclical companies revealed that fewer than 20% are genuine long-term “owners”—holding their investments through full market cycles (five years or more). In contrast, approximately 80% approach cyclical stocks primarily as short-term trading vehicles, with median holding periods of only two to three years (shorter than for non-cyclicals). To underscore the point, approximately two-thirds of investors in cyclical sectors seek short-term “torque” from commodity price fluctuations—treating stocks as trades, not long-term investments.

Investors’ short-term perspective contrasts sharply with management’s multi-decade asset commitments, further exacerbating executives’ difficulty in maintaining discipline across economic cycles.

Beating the Cycle: What the Best Get Right

Given cyclical-sector volatility, distinguishing management skill from luck can be difficult. To draw practical lessons for managers, we analyzed the performance of 240 cyclical companies over 30 years. Our analysis identified 42 companies that reliably outperformed their peers throughout multiple economic cycles. (See “About the Study.”) Over the time period, these companies delivered an average ten-year TSR of approximately 18%, outperforming their subsector median by an average of approximately ten percentage points. Simply put, a dollar invested in these high performers three decades ago would today be worth approximately $140, compared with approximately $10 if invested at their peers’ median levels.

About the Study

Additionally, in April and May 2025, we surveyed 150 institutional investors and interviewed investors, C-level executives, and former members of boards of directors in cyclical sectors.

What distinguishes these consistently successful companies is their ability to maintain robust performance across multiple market cycles—evidence that their success reflects deliberate strategic choices rather than luck. By examining their long-term track records across cyclical sectors (instead of within a given sector), we identified common behaviors that other management teams might emulate to achieve through-cycle outperformance.

Disciplined Capital Allocation: Winning Without Timing the Market

“CEOs today are portfolio managers—their job is to allocate capital. They’re constantly remaking the business by recycling the capital invested in the business every five years,” explained one investor. While capital allocation is relevant for all businesses, it is particularly important in capital-intensive cyclical sectors where management will reinvest 70% to 100% of the total company value over a typical five-year period (versus approximately 50% in non-cyclical sectors). Unsurprisingly, through-cycle TSR outperformance in cyclical industries is predicated on superior capital allocation.

“CEOs today are portfolio managers—their job is to allocate capital.”

— Investor

Winners distinguish themselves by using disciplined processes to see through economic cycles—even when this results in moves that appear inconsistent with immediate short-term interests. Critically, we found that consistent high performers do not outperform by repeatedly timing the market (a task that is notoriously difficult to do). Instead, they’re defined by more stable capital allocation through the cycle. This stability is reflected in their higher dividends, more consistent M&A and buybacks with reduced cyclical swings, and more conservative through-cycle debt levels.

Successful companies’ methodical allocation is supported by three complementary processes described below.

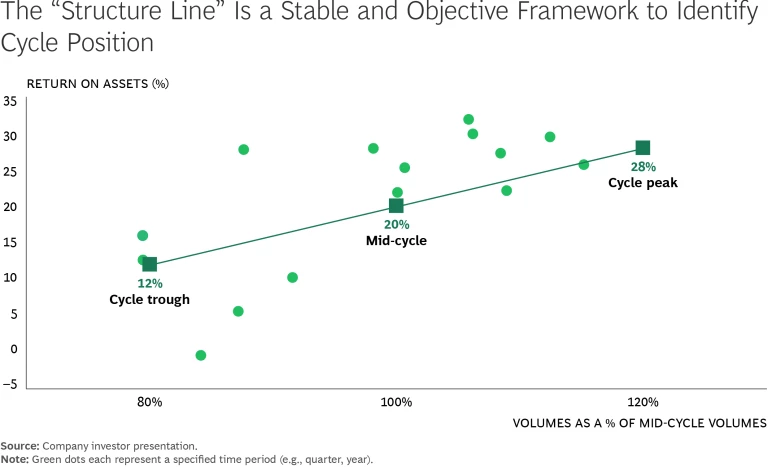

Improve decision making by using a stabilized through-cycle approach. High-performing companies consistently ground their decisions in a stabilized through-cycle approach that is anchored in long-term market data. Rather than attempting to predict the market cycle, such an approach objectively measures current conditions relative to a normalized mid-cycle benchmark. This analytical clarity and institutional memory help set realistic expectations regarding profit margins and returns on assets, enabling informed, disciplined decisions across all market environments.

“In cyclical sectors, you need conviction in your long-term fundamentals to avoid overreacting during short-term downturns.”

— Executive at major oil and gas company

As one experienced agriculture CFO explained, “We use an analytical set of tools that gives us rigorous and robust language for understanding our industry position versus a mid-cycle normal.” Echoing this perspective, an executive at a major oil and gas company emphasized, “In cyclical sectors, you need conviction in your long-term fundamentals to avoid overreacting during short-term downturns.” This rigorous long-term perspective empowers management teams to secure board alignment and resist short-term pressures or impulsive reactions during market swings. (See “An Agriculture Company Uses the ‘Structure Line’ to Anchor Strategic Decisions.”)

An Agriculture Company Uses the “Structure Line” to Anchor Strategic Decisions

In practice, the company compares current volumes to mid-cycle volumes to inform both day-to-day operations and strategic planning. For example, volumes that are at 120% of normal are at the cycle peak, and the company adjusts performance targets accordingly.

The company’s leadership dynamically scales performance and operational targets—such as return on assets, profit margins, production targets, and inventory levels—to accommodate current market conditions (for example, operating at 80% or 120% of mid-cycle volumes). This ensures that management is rewarded for execution relative to objective cycle-adjusted targets, not for market timing. As one executive stated, “We can’t control the market, but we can control our execution. Rather than getting paid for the external environment being favorable or not, you earn your bonus depending on whether you added value and overperformed after adjusting for the cycle’s tailwinds or headwinds.”

Each business unit annually models its cost structure at three defined points in the cycle—typically representing cycle trough, mid-cycle, and cycle peak—and identifies specific levers that can be activated as conditions evolve. This planning discipline forces leadership to recognize the cycle position and enables the company to execute preapproved actions quickly when early signals of a downturn or recovery emerge—for example, curtailing production quickly in response to demand softening well before reported margins are under pressure.

Beyond operational planning and performance management, the structure line is embedded in the company’s strategic and capital allocation decisions. It serves as a cycle-adjusted baseline for evaluating investment proposals based on expected mid-cycle returns and financial implications at the trough.

In addition, high performers typically have longer management tenures and codified institutional memory, increasing the likelihood that leaders can recognize cycle dynamics and avoid being overly reactive to current conditions, whether bullish or bearish.

Successful companies apply (and reinforce) this approach in several tangible ways:

- Capital Allocation. High performers consistently assess investment decisions based on mid-cycle return potential, rather than the current near-term market outlook. This often means evaluating long-term investment decisions using a long-term average historical commodity price or a fundamental view on producer economics.

- Investor Communication. Winners give investors a clear view into how their decision making adapts across the economic cycle. They consistently articulate (and repeatedly reinforce) the criteria that guide capital allocation—whether to pay down debt, reinvest, repurchase shares, or return capital—based on guardrails regarding cycle position and long-term value creation potential.

- Performance Assessment. Leading companies assess (and reward) management performance using operational metrics that are directly within management’s control, such as production per share. Importantly, they evaluate performance within the context of the cycle, consistently recalibrating operational expectations to reflect prevailing market conditions.

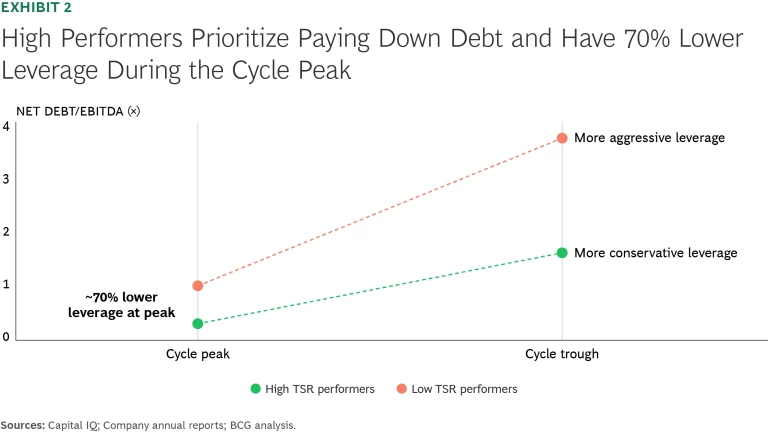

Limit peak debt to levels sustainable with trough cash flows. High performers view their balance sheets as prized strategic assets that provide both safety and flexibility during downturns. As one investor observed, “In cyclical sectors, survival is more important than maximizing gains in the good times.” Winners prioritize debt reduction and strong cash positions during economic expansions, positioning themselves to seize strategic opportunities during downturns. (See Exhibit 2.)

Applying this disciplined approach can be challenging. Management does not know precisely when the cycle will turn or how severe the next downturn might be, making it difficult to evaluate downside risks to cash flow and the resulting debt service coverage ratios. Successful companies establish clear, internally determined debt thresholds based on stress-tests and historical cash flow levels during cycle troughs. Rather than relying on near-term forecasts, they manage to these internal benchmarks, ensuring that their balance sheets remain resilient throughout the cycle.

Allocate capital consistently through the cycle. High performers allocate capital consistently through the cycle. This is enabled by their stabilized through-cycle approach and strong balance sheet, which position them to invest during troughs while their lower-performing peers are forced to pull back.

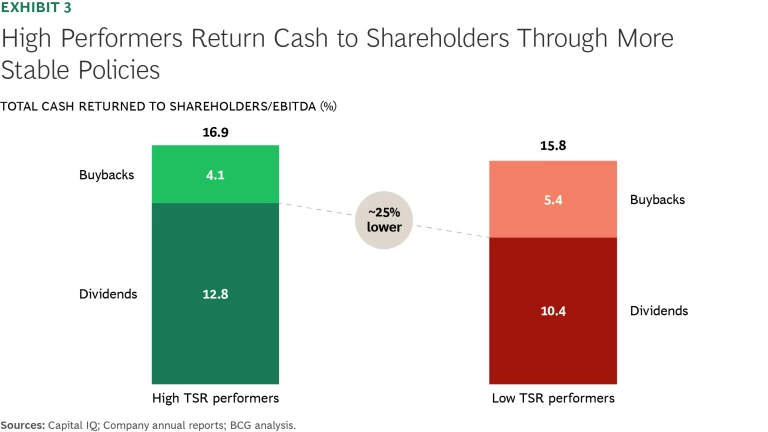

Leaders maintain a dividend-to-EBITDA ratio roughly 25% higher than their lower-performing peers.

Dividends are the foundation of this approach. High performers return more of the cash they send to investors in the form of steady dividends rather than buybacks. They maintain a dividend-to-EBITDA ratio roughly 25% higher than their lower-performing peers. (See Exhibit 3.) Beyond signaling greater conviction in the durability of cash flows, returning cash through stable, regular dividends imposes discipline. Management must carefully prioritize the highest-value growth opportunities while dampening the impulse to act cyclically.

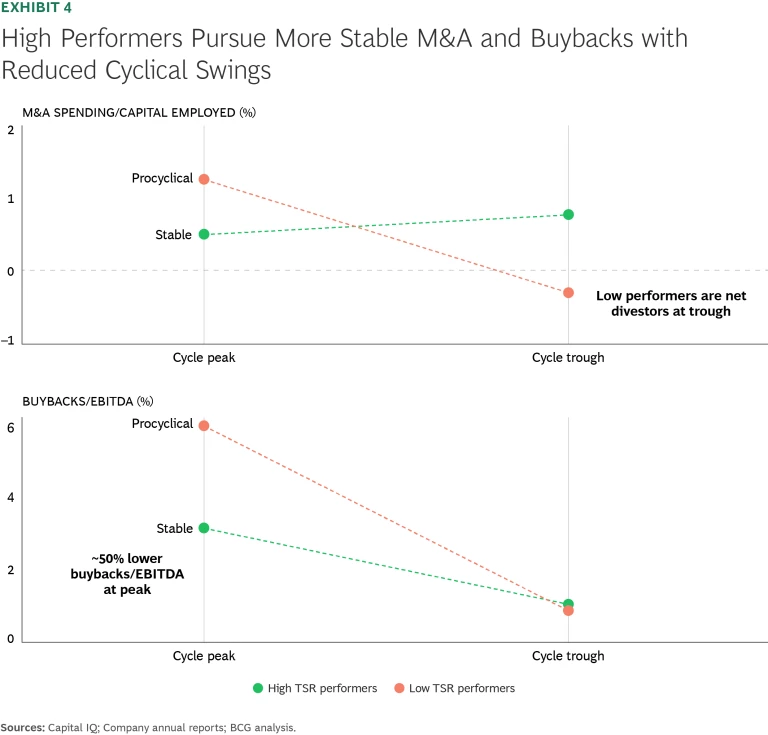

That same philosophy extends to discretionary capital. Whether in acquisitions or buybacks, high performers maintain a more consistent allocation than their lower-performing peers. (See Exhibit 4.)

As with debt management, consistent capital allocation across the cycle is easier said than done. Sustaining investment during economic downturns—when returns are compressed, cash flows are constrained, and external pressures mount to reduce capital outlays—requires conviction and clarity.

Successful companies establish clear and objective metrics to guide capital allocation and force discipline. For example, one high-performing company links buybacks to a defined stock price-to-net asset value threshold and, in doing so, positions its organization to execute value-enhancing buybacks when shares are undervalued rather than simply when cash is abundant. Another leading company evaluates economic decisions based on a mid-cycle outlook rather than commodity strip pricing, enabling it to continue investing in organic growth opportunities, even during cycle troughs.

In addition to avoiding cyclical mistakes, this rigor enables high performers to conduct arbitrage across opportunities. They force capital to compete across all investments—including organic investments, acquisitions, buybacks, or even buying a peer’s stock. While this may lead to politically difficult decisions—such as postponing organic growth in favor of accretive share buybacks—it reinforces a stable and disciplined environment that drives long-term TSR outperformance.

This structured approach gives management the conviction to act decisively and reinforces the principle that discretionary capital spend is a privilege, not a right—each dollar must be deployed to its highest-value use. These mechanisms enable the ultimate goal in cyclical sectors: more stable capital allocation.

Is Your Company Ready for Through-Cycle Outperformance?

Discipline is easy to admire and hard to maintain, especially when times are good. And if you have tried to build it before—but found it hard to sustain—you are not alone. The key is to treat discipline not as a one-time initiative but as a stable system embedded into how the organization makes decisions across cycles.

So how should a company begin to institutionalize such a system? The first step is to assess your starting point. CEOs and CFOs of cyclical companies should bring the following questions to their next leadership team meeting:

- Do you employ an unbiased through-cycle approach to determine your current position within the cycle based on historical data? Do you use that lens to evaluate investments based on their mid-cycle return potential?

- Do you independently stress-test investment decisions and set debt thresholds based on trough cash flows?

- Do you regularly evaluate growth investments against alternatives—such as dividends, share buybacks, or purchasing the stock of peers—to ensure optimal use of investor capital?

Answering “no” to any of these questions indicates potential vulnerabilities in your ability to effectively deliver through-cycle performance. In that case, the imperative is clear: identify where discipline slips and reinforce it with systems that make the right course of action—anchoring decisions in mid-cycle frameworks, managing debt prudently, and objectively evaluating all capital deployment options—the natural one, even when cycle conditions make other paths more tempting.

Too often, successful countercyclical moves are portrayed as brilliant strokes of timing. While individual cases of inspired (or lucky) timing do occur, relying on timing is not a sustainable formula for long-term success. As the fable of the ant and the grasshopper illustrates, disciplined preparation is the foundation of consistent outperformance. By embedding stable long-term thinking into how they make decisions, manage debt, and allocate capital, executives across all sectors can confidently navigate market volatility and secure resilient value creation. Timing is tempting, but discipline delivers.

The authors thank Jaime Ruiz–Cabrero, Karthik Valluru, and Ben Fletcher for their contributions to this article.