Across the globe, governments are increasingly asserting export controls over digital infrastructure, AI models, quantum computing, cloud platforms, and other cutting-edge technologies in the interest of national security, military modernization, and global influence. The new reality for IT and R&D departments is that routine technology decisions—such as where to train, host, or update—now carry commercial and regulatory consequences for how, where, and even whether they can compete.

As these issues have moved front and center, the way companies design, build, and deliver digital products now determines their regulatory exposure. That means compliance design is no longer a peripheral concern but is integral to a company’s product and business strategy, governing where it can operate, how fast it can scale, what features it can offer across jurisdictions, and how quickly it can deploy those features.

The companies that win in this new environment won’t just manage compliance, they’ll turn it into a competitive edge, allowing them to launch products faster, avoid architectural debt, and unlock growth markets others are forced to exit. Leaders in the C-suite and on the board should therefore promote action aggressively along two complementary paths: embedding stronger compliance capabilities and using regulation as a critical product design input.

Trade Rules and Competitive Realities Are Changing

While physical goods still dominate trade by volume, the strategic center of gravity is shifting toward those who control technology, software, algorithms, and digital infrastructure. The frontline of trade is moving from ports to platforms.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the global race for AI dominance, where governments are moving to control not just who can access the most advanced models, but also the compute capacity and chip manufacturing tools required to train them. What began as narrow controls on semiconductors has expanded into a broader contest over data, infrastructure, and algorithmic power. For example:

- In the United States, trade restrictions now extend well beyond traditional export controls. Deemed export rules still apply to software and AI access but are now part of a broader framework including nationality-based exclusions, ICTS regulations on foreign tech in critical infrastructure, and sweeping chip and IP controls. Industrial policies like the CHIPS Act continue to promote domestic semiconductor manufacturing as a means of reducing exposure to foreign supply chains.

- In the European Union, software and AI tools can be subject to dual-use controls if they have potential military, surveillance, or encryption functions. Even intangible transfers via email, download, or remote access are treated as exports. Regulators assess not only what the software does but who will use it and for what purpose.

- In China, export controls extend beyond traditional goods. Companies may be required to register algorithms, restrict re-exports, and localize certain services. Foreign-developed software can fall under Chinese controls if retrained or deployed on local infrastructure. Jurisdiction increasingly follows where data is processed, not just where code is written.

The commercial implications are escalating. To satisfy regulators in different jurisdictions, some companies are already fragmenting their software architecture or choosing to walk away from key markets altogether. For example, in the automotive sector, OEMs are splitting their software stacks into variants for the US, European, and Chinese markets to avoid entanglements, and Western OEMs are developing separate advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) “in China for China,” even when the non-ADAS vehicle hardware is identical to the vehicle hardware made for other markets.

The Hidden Risks in Intangible Tech Transfers

For decades, export controls were triggered when a physical product crossed a border. But that model doesn’t fit how digital technology works or how value is created. Modern export regimes now treat intangible transfers—such as access to code, model logic, or updates—as legally equivalent to the shipment of hardware.

As a result, trade risks hide in routine, upstream activities that no longer feel like exports at all, such as sharing AI weights across global teams, migrating cloud workloads to lower-cost regions, or activating a new feature postsale. Each of these actions can trigger export obligations, and they happen by default in fast-moving, distributed tech organizations driven by product managers, R&D teams, software engineers, and cloud architects. (See “How Export Risk Materializes in ADASs.”)

How Export Risk Materializes in ADASs

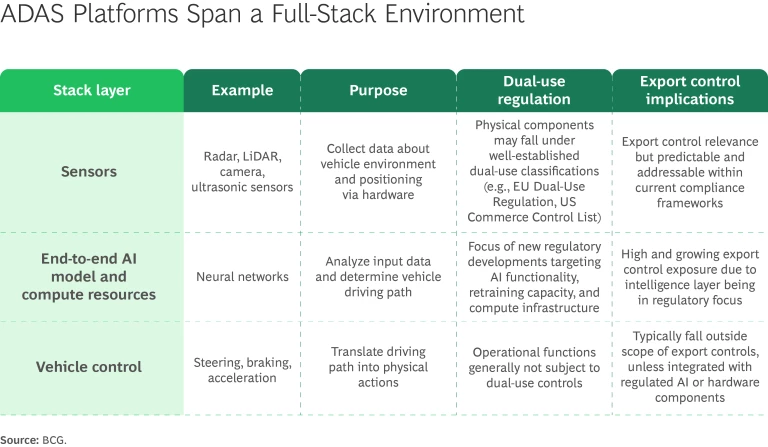

That is much more difficult with E2E AI stacks. ADAS platforms span a full-stack environment, from in-vehicle sensors and embedded software to cloud-based analytics and self-learning models that evolve postsale—through regular retraining, back-end logic updates, and over-the-air (OTA) feature releases. (See the exhibit below.)

And the potentially high-risk components in ADAS software are not limited to AI models. They span sensor inputs, cloud infrastructure, and OTA update mechanisms, creating a persistent and layered compliance challenge. For example:

- AI models used for decision making are often classified as dual use, especially when trained with sensitive or jurisdictionally bound data.

- High-definition maps are subject to strict regulatory frameworks in certain jurisdictions, with rules governing data storage, enrichment, and usage.

- OTA and back-end systems create continuous export triggers; every update or retraining cycle can constitute a new export event.

- In-vehicle systems on a chip often include US-origin IP, pulling otherwise EU- or China-based stacks back into the scope of US Export Administration Regulations.

In other words, what makes ADAS particularly exposed isn’t just the technology, it’s how that technology is built and deployed. These risks are systemic, recurring, and deeply embedded in how ADAS functions and evolves.

Yet CIOs, software architects, and R&D leaders often lack the ability or ownership structures required to detect these triggers before they escalate. They need a business-wide view. Trade compliance is not merely an operational task, and regulation is not merely a downstream checkpoint. These are strategic concerns that shape where and how companies can grow.

Featured Insights: Explore the ideas shaping the future of business

Two Paths to Winning in a Fragmented Tech World

The best companies don’t just adapt to this new reality. They lead by pursuing two complementary paths. They build stronger compliance capabilities that are embedded in their operations. And they act entrepreneurially, using regulation as a design input to create speed, resilience, and market differentiation. They turn fragmented regulation into a business advantage. Precision, not scale alone, is the new competitive edge.

Build for compliance: Operate with speed, discipline, and control. In an environment of fast-moving code and jurisdictional complexity, companies must modernize their management of trade compliance by designing an operating model that moves at the speed of engineering. When done right, compliance becomes a capability—not a constraint. It prevents last-minute license delays, reduces rework, and enables faster, more predictable go-to-market plans. To follow this path, companies must:

- Appoint a clear compliance owner with reach across legal, engineering, and product design.

- Classify sensitive components—AI models, cryptographic modules, retraining pipelines—from day one.

- Embed export logic into build systems, continuous integration and continuous delivery/deployment pipelines, and release tooling.

- Use automated flags for export triggers, such as cloud migration, retraining, and over-the-air (OTA) updates.

- Train engineers and product teams to recognize and act on jurisdictional risks.

Act entrepreneurial: Design for advantage, not just compliance. Entrepreneurial leaders treat regulation not just as a constraint, but as a lever to reshape how they build tech and design products. At the heart of this approach is smart segmentation. Instead of duplicating entire stacks—one for the US, one for the EU, one for China, and so on—strategic players isolate only the 20% to 40% of their architecture that triggers regulatory friction (such as perception models, OTA logic, or encryption flows). The rest of the stack remains global. By localizing only where necessary and maintaining global scale, companies reap substantial cost and speed advantages.

But architecture is just the start. Winning companies also rethink what they offer—and where. They use regulation to shape product architecture, go-to-market strategy, and innovation faster than competitors constrained by legacy thinking. To follow this path, companies must take a number of steps in the following areas:

- Product and Market Strategy. Simplify features or shift to local service delivery in high-friction markets to reduce export scope. Double down on feature-rich bundles in core markets to retain update rights and speed. Sequence market entry deliberately, prioritizing regions with favorable licensing conditions or geopolitical alignment.

- Technology and Architecture Choices. Restructure IP ownership and access, separating sensitive modules geographically and using internal licensing to control developer access across jurisdictions. Reevaluate make/buy/partner decisions, especially for high-friction components exposed to export controls or sanctions. Form tech partnerships to access cleared components, enable local delivery, or co-own licensing responsibilities.

- Business Planning and Execution. Factor compliance costs into core business decisions, including pricing, launch timing, and product roadmap investment.

- Stakeholder Engagement and Positioning. Engage regulators early to clarify scope, accelerate approval, and shape the playing field. Promote the company’s compliance strategy as a commercial differentiator.

Don’t Just Comply—Compete Smarter

Export risk now lives inside the codebase—not at the border. What used to be a downstream legal check has become a strategic constraint on how companies build, scale, and operate globally. Ignoring export risk delays launches, fractures product lines, and quietly erodes market access.

Companies that get ahead of this shift won’t just avoid disruption, they’ll gain strategic advantage. There are five questions leaders should be asking right now:

- Do we have a clear, cross-functional view of where export risks live in our products and processes today?

- Where are we unintentionally triggering export obligations through training, updates, access, or infrastructure decisions?

- Does our current technology strategy support differentiated stacks where needed, or are we trying to make one architecture fit everywhere?

- Who in our organization owns life cycle compliance—and does this person have the mandate, tools, and visibility to act?

- Have we embedded export logic into our development, deployment, and product governance processes, or are we relying on manual reviews and late-stage checks?

In BCG’s experience, companies that connect the dots early—embedding compliance requirements into product design and configuration—will move faster, scale smarter, and outcompete in markets that others can no longer serve. The goal is not just to avoid mistakes, it’s about managing fluid and uncertain export regulations with a smarter strategy for greater advantage.

The authors thank their BCG colleague Marc Brunssen for contributions to this article.