The UK is at a crossroads when it comes to the nation’s health. In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, pressures on the healthcare system have continued to rise despite health spending being at record highs. From the rise in waiting lists to the impact of ill health on work, there are several complex and interconnected challenges that need to be addressed as a priority.

Tackling these sorts of complex issues requires a new approach. The healthcare system alone cannot address the wide-ranging drivers of long-term sickness and ill health. Over 50% of health outcomes are influenced by non-healthcare factors, such as environmental conditions, lifestyle and social networks.

It is not just a case of throwing more money at the issue, though investment will be required. Too often the public sector is set up to treat the symptoms of a problem rather than an underlying cause. To tackle the fundamental drivers and root causes of ill health, we must go further and think more dynamically through a whole-of-government approach (WGA).

This means looking at health as a priority across all areas of policy, with departments, agencies and partners taking a joined-up approach to health and wellbeing that is outcome-first focused.

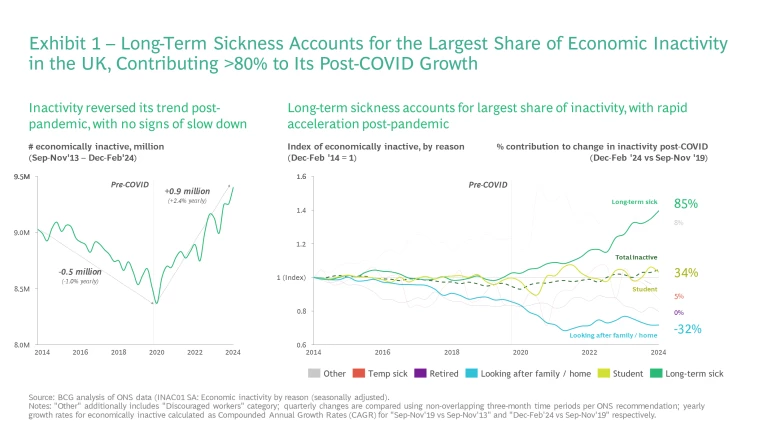

A prime example of this sort of complex challenge is seen in the stark rise in the number of people out of the workforce due to long-term illness. Since 2020 alone, economic inactivity in the UK has risen by 900,000 people, with 85% of this increase due to those who are long-term sick. Currently, around 375 million workdays are lost because of people being out of the workforce due to long-term sickness.

While the early post-pandemic days saw a rise in those taking early retirement or remaining in education, these trends have reversed. The two main groups now driving the recent rise in long-term sick economically inactive are now: 18-24-year-olds and 50-64-year-olds. The rise among 18-24-year-olds is very concerning given this should be the healthiest group in the population.

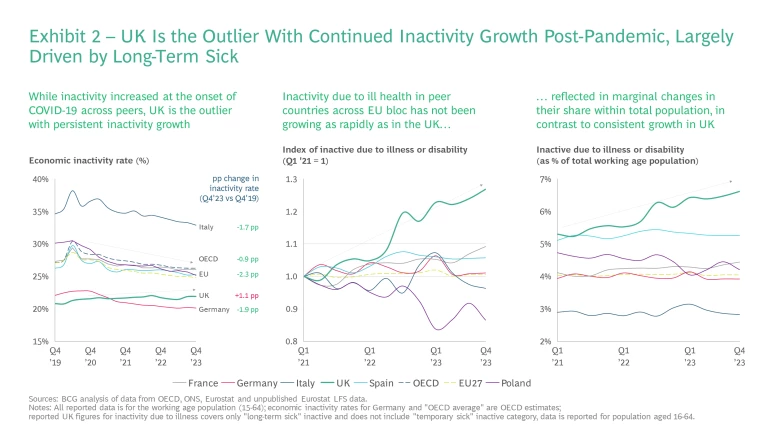

The UK is an outlier among its peers here. On average EU countries have seen economic inactivity fall by 2.3 percentage points, while the UK’s has risen by 1.1 percentage point since 2020.

The rapid and sustained rise in economic inactivity and long-term sickness, not only has significant impacts on affected individuals but also significant fiscal and economic costs for the nation. We estimate that reducing long-term sick inactivity could boost the UK’s GDP by £109-177 billion and fiscal revenue by £35-57 billion over the next five years. Exhibits 3.1 to 3.3. below show the detailed breakdown of these estimated benefits, which derive from two aspects:

- Reintegrating 0.3 to 0.6 million people who became long-term sick inactive from 2019 into the labour force.

- Reverting long-term sick inactive growth rates back to their long-term trend of around 0%, by preventing the active population from entering inactivity due to sickness.

The estimated ‘size of the prize' for tackling long-term sick inactivity is significant in any context. However, in the context of an increasingly challenging fiscal landscape in the UK, it signifies a genuine opportunity to not only improve population health, but also to improve the UK’s fiscal position and help drive economic growth.

Addressing this important issue will require co-ordinated and early intervention that approaches the drivers of ill-health and economic inactivity holistically and seeks to tackle the underlying drivers. Our new quantitative analysis of the wider social and environmental determinants of health reinforces this and shows that:

- Social and environmental determinants are often more important to health outcomes than clinical or behavioural factors, such as diet and exercise. For example, economic and working conditions explain more of the variance in health outcomes across England than behavioural choices.

- For some counties—depending on their performance compared to the rest of England—investing in tackling wider determinants could have more impact on health outcomes than investment in behavioural factors.

- Over the past seven years, changes in living conditions and crime are the factors that have driven most significant changes in health outcomes.

This and the fact those who are economically inactive due to ill health interact with many different parts of the healthcare system, only reinforces the need for a whole-of-government approach. There are three key barriers which often prevent or hamper such cross-government working and which any whole-of-government approach to health must address:

-

A common purpose: drive buy-in across all levels of the system for action on major complex challenges such as long-term sickness driving inactivity. -

Collaboration and place-based decision-making: with accountability structures that incentive collaboration and local-based decision-making. -

Joined-up funding and resources: that facilitates longer-term funding horizons where government has a shared view on how to maximise economic and social benefits from health investment and health is a cross-cutting Treasury priority.

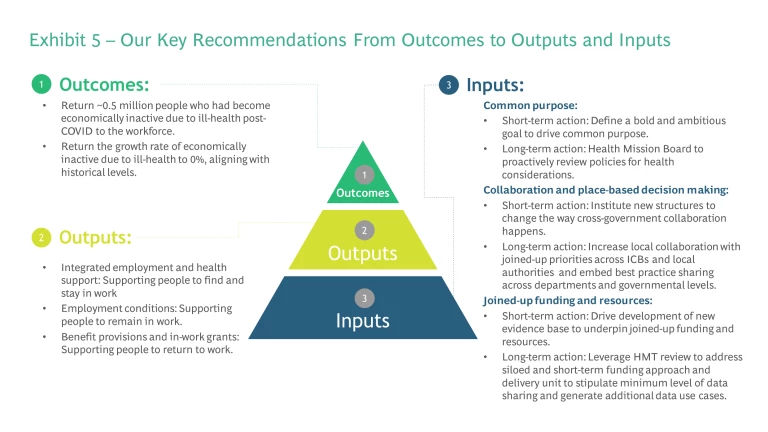

To deliver a fundamental change in how problems are tackled, government needs to reverse the way it approaches cross-cutting strategy work. Instead of taking the inputs it is working with as set, then establishing feasible outcomes off the back, outcomes should be targeted first, with inputs and outputs designed around cross-cutting outcomes.

With that in mind we outline a series of actions which can help successfully deliver a whole-of government approach to health, with a specific initial focus on addressing the challenge of economic inactivity driven by long-term sickness. This could equally apply to other health issues or any broader WGA.

The government should set the following outcomes targets:

- Return ~0.5 million people to the workforce, who had become economically inactive due to ill health post COVID-19.

- Return to 0% growth in the number of people economically inactive due to ill health.

To achieve these outcomes, the government could target several policy outputs which can be better facilitated by a WGA. These require action from both the public and private sector to be truly effective:

- Integrated employment and health support: supporting people with health challenges to get back into the workforce.

- Employment conditions: support to keep people working rather than dropping out.

- Benefit provisions and in-work grants: incentivising people to return to work by reducing risk.

Finally, government must reorganise the underlying inputs when it comes to setting up and delivering a WGA. Organising inputs to breakdown the key barriers to tackling cross-cutting issues which cause ill-health and long-term economic inactivity. We believe these comprise a series of immediate- and longer-term actions that apply to the wide range of the social and environmental determinants of health:

Common purpose

-

Short term – Define a bold and ambitious goal to drive common purpose across government. -

Long term – Leverage the new Health Mission Board to establish a Health Improvement Strategy and to proactively review policies for health considerations enabling faster more joined-up action across government.

Collaboration and place-based decision-making

-

Short term – Institute new structures to change the way cross-government collaboration happens, including a novel approach to mission boards. -

Long term – Increase local collaboration with joined-up priorities across ICBs and local authorities and embed best practice sharing across departments and governmental levels.

Joined-up funding and resources

-

Short term – Drive development of a new evidence base to underpin joined-up funding and resources. -

Long term – Leverage this evidence base to address siloed and short-term funding approach and design to incentivise data sharing across all levels of government.

About Us

BCG's Centre for Growth brings together ideas, people and action to drive the UK forward. We work with our global expert network to identify transformational opportunities, connect key decision-makers and build coalitions for change. We offer long term strategic insight, extensive cross-sector expertise, platforms for dialogue and bias to action.

The NHS Confederation is the membership organisation that brings together, supports and speaks for the whole healthcare system in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The members we represent employ 1.5 million staff, care for more than 1 million patients a day and control £150 billion of public expenditure. We promote collaboration and partnership working as the key to improving population health, delivering high-quality care and reducing health inequalities.