Company leaders launch change initiatives with good intentions. They’ll send carefully crafted emails and make energetic speeches telling employees how the way they work will transform for the better. We often embody the same enthusiasm in our personal lives: this is the year we’ll eat healthier and exercise more!

But achieving change is difficult. Organizations spend more than $10 billion annually on change transformations,

To better understand why, despite our best intentions, change efforts tend to fail, we looked to the literature—and found that “loss aversion” presents a helpful point of reference. This established psychological concept states that people hate loss more than they love a gain of equal magnitude; for example, the pain of $5 falling out of their pocket is psychologically twice as powerful as finding $5 on the street. We believe people view change in a similarly emotion-charged way. Like loss, they think of change as negative, and that emotion overwhelms their ability to consider the potential benefits. In other words: people are change-averse.

Interestingly, company leaders seem to recognize the concept of change aversion when it comes to customer attitudes and behaviors. Organizations have the capabilities to study customers’ feelings and to adjust their go-to-market strategies accordingly. For example, companies often invest heavily in understanding how to transform a consumer from a monthly buyer to a weekly buyer or convert an impulse purchase into a shopping cart staple. But organizations rarely extend the same effort to understand the behaviors of their own employees, instead focusing on the business rationale for change without considering the human element.

This is a critical blind spot: if employees are innately inclined to dislike or resist change, they will shrink from it. By understanding what drives and modulates change aversion, organizations can improve the probability of success for their transformation initiatives.

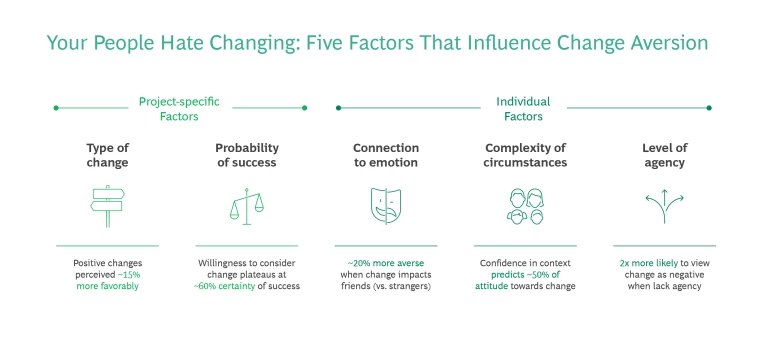

To better understand this phenomenon, we surveyed more than 200 people across the US about their feelings toward change. Our survey sample was balanced by gender. Most respondents were between the ages of 25 and 55, with even distribution among individual contributors and managers. Based on our analysis, we identified two categories of factors that influence change aversion: factors specific to the change initiative and those specific to the individual (see exhibit).

Factors Specific to the Change Initiative

Factors inherent to the initiative itself have less influence on an individual’s degree of change aversion than more personal factors do. But the former still offer leaders helpful insights when planning and executing their transformations.

1. The type of change proposed. Not surprisingly, a negative change for individuals, such as a pay cut, will lead them to feel more averse than a positive change, such as a pay raise. Yet even when a change may appear advantageous for the organization, such as a more efficient process, employees still may experience a loss of routine and comfort. It’s therefore not always easy to characterize change as “positive” or “negative” at an organizational level.

What this means for leaders: Differentiate between what a change means for the company versus what it means for an individual. Given that the on-the-ground impact might be challenging for employees, leaders should be upfront about these difficulties and provide resources and support. And when a change is positively received by employees (and ideally has positive quantifiable results), leaders should celebrate this impact and credit people for their efforts.

2. The probability of success. The certainty of a change initiative’s success has less influence on change aversion than expected. More than half of respondents needed just about 60% confidence in the anticipated results to consider making a change; less than 10% of respondents needed 80% confidence. We tested scenarios such as choosing a healthier eating routine to lose weight and adopting a new computer system to speed up work. In both cases, one deeply personal and one external and distant, the confidence in the likelihood of success did not make much of a difference in people’s openness to making that change.

Moreover, even a near-guarantee doesn’t always force action. In the early 2000s, researchers studied patients who had a history of cancer and therefore had increased risk for secondary tumors, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and potentially other fatal conditions. These patients were told by trusted physicians that if they didn’t make specific lifestyle changes—such as increasing physical activity, focusing on nutrition, and not smoking—they could be dead within just a few years. Fewer than 10% were able to make sustained behavior shifts.

What this means for leaders: Talking about the benefits of a proposed change in terms of data points and probability might win some people over, but will only get you so far. CEOs often spend countless hours massaging their messaging to boost the perceived odds of success. Based on our research, that’s not necessary. A more effective strategy may be to lay out the facts for employees and take them along in the journey as co-captains. Employees time and again show greater willingness to change when they feel a sense of shared ownership in the full “change process” (an idea we’ll return to later).

Factors Specific to the Individual

Acknowledging emotions and understanding how individual factors influence change aversion may be as important as factors inherent to the initiative itself. Yet we find that leaders often miss this critical component.

3. The connection to emotional needs. People are more averse to change when it affects them emotionally—for example, by straining work relationships—than when a change impacts them functionally, such as incorporating a new task into their routine.

We asked respondents to make difficult choices, serving as either the “decider” (the CEO of the company) or as the “advisor” (an employee making recommendations to the CEO). When deciding whether to conduct layoffs in a challenging business environment, the respondents acting as CEOs were more likely to opt for the cost-cutting program than those acting as advisors (whose direct peers were under consideration for layoffs).

We posit that the latter groups’ proximity to those affected was the driving factor of their hesitation. When the advisors knew that some of their closest friends at the organization would be laid off, the number of people against the change went up to 45%, compared to 27% if they did not know anyone affected.

What this means for leaders: Identify ways to capture how people are feeling and coping before, during, and after a change program. Building the institutional muscle to gain real-time insight into employees’ emotions through pulse checks and manager check-ins has proven to be effective on many fronts. A case study at Ubiquity Retirement + Savings—where people literally “punch-out” with their strongest-felt emotion of the day (from smiley face to frowny face)—revealed that this practice is not an HR gimmick: it spurs creativity and better teamwork and improves work quality.

Change leaders should also be cognizant of the ripple effects of seemingly un-emotional changes. A scheduling change might not seem like a big deal, but if it means that a parent won’t be able to attend her daughter’s soccer practices, then it becomes very emotionally charged.

Leaders often neglect to consider how employees’ individual circumstances influence their feelings about change.

4. The complexity of an individual’s circumstances. People have varying levels of “change insurance,” meaning they have different resources (money, time, emotional bandwidth) to deal with change. We found a positive correlation between people’s belief that they have enough “insurance” to handle daily responsibilities and their attitude toward personal and professional changes.

Consider the remote work shift during COVID. Senior members of organizations may already have had home offices, or at least the space to create one. Compare this to the experience of junior employees who may have been living with roommates, or parents who suddenly had to juggle working from home with their children’s virtual schooling. Employees who might superficially appear quite similar likely have varying sets of circumstances that influence how they handle change.

What this means for leaders: Understand that changes might impact two people in the same role completely differently. Some people are more able to accept and thrive amid certain changes at certain moments than others. Developing a sense of where people may be in their ability to handle a change will allow for more personalized ways of engaging them and lead to more successful change outcomes.

Organizations can draw upon a broad set of resources to increase employees’ change insurance. Examples include providing stipends to cover the costs of home-office set-ups for hybrid workers (such as Box, Calm, Shopify) or offering flexible schedules to give parents more time for childcare drop-offs and pick-ups (such as Marriott, Patagonia).

5. The employees’ level of agency in making or deciding on a change. We found that respondents were twice as likely to feel negatively about an employer-imposed change (being assigned new responsibilities) than a self-imposed change (managing their own time more effectively).

The notion that people are more resistant to change when they have less agency is not new. In fact, giving workers more agency is a recommendation in Lester Coch and John P. French’s seminal 1948 article “Overcoming Resistance to Change.” However, we believe that change management practitioners have yet to fully embrace this ideal.

What this means for leaders: Resistance to change can be turned into a learning opportunity—a chance for leaders to incorporate employees’ opinions on how to make a change successful. Even an imperfect change program that the implementers believe they have a stake in is far more likely to succeed than a top-down initiative. This is yet another example of the so-called IKEA effect. Studies since the 1950s (beginning with instant cake mixes) have shown that if people “do it themselves” they see their own creations “as valuable as those of experts and expect others to share their opinions.”

How does this translate to a change initiative? Involve employees early and build opportunities for them to suggest how the change can best be implemented. But take note: leaders should only solicit this feedback if they plan to incorporate it. Paying lip service to employees’ ideas and concerns will lead to broken trust, which can heighten resistance to change.

To improve the probability of success for organizational change efforts, we must update the paradigm of change management to reflect human behavior. Leaders who are willing to better understand people’s natural change aversion will be met with less resistance, more engagement, and better outcomes.

The author team deeply appreciates the invaluable contribution of Milo Tamayo, whose original research made this article possible.