Today’s business environment is characterized by rapid, extensive change and unpredictability. The combined effects of digitization, connectivity, globalization, demographic shifts, and social feedback are shaking the foundations of almost all businesses, making sustained growth more valuable and elusive than ever before. In addition, we see that companies—at a time when adaptiveness is so crucial—are often hampered by internal complexity that makes change difficult.

To compound matters, the diversity of the business environments—in terms of growth, rate of change, and harshness—that global companies face is expanding in a multispeed world. So it is not surprising that many companies find their strategies and business models increasingly out of step with their environments.

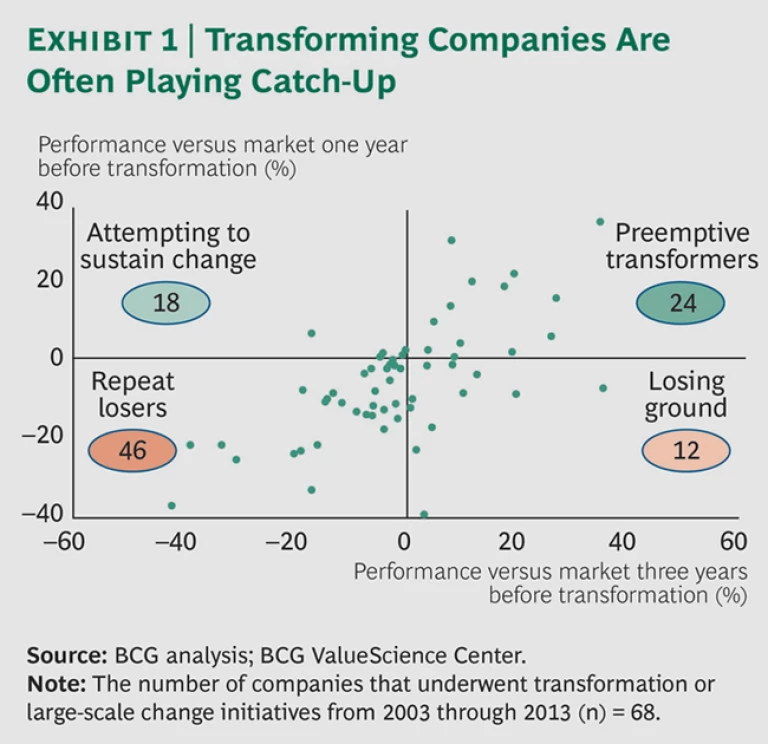

Many companies get caught in a “boiling-frog trap,” where they fail to recognize the problem and delay efforts to remedy it, thus necessitating a painful and risky step-change transformation. Our analysis suggests that, prior to embarking on such change efforts, fewer than a quarter of companies have outperformed the market and nearly half are systemic underperformers. (See Exhibit 1.)

And while transformations are increasingly common, we know that about 75 percent of such efforts fail to restore long-term growth and competitiveness. Logically, that’s hardly surprising: jumping is inevitably riskier than walking, especially when the bar is high. And often the company’s focus is on healthy quarterly earnings rather than sustained competitiveness, encouraging management to adopt a stance of “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” Waiting until performance is already declining, however, not only increases the magnitude of the required adjustment and the organizational difficulty of realizing it but also puts companies in a reactive position, causing them to miss opportunities for preemption, experience building, leadership, and, ultimately, competitive advantage.

There are understandable reasons why companies fail to preemptively transform themselves in the face of change. A company might, for example, do the following:

- Foster a culture that marginalizes new, dissonant perspectives, causing the company to miss or minimize important change signals

- Lapse into a false sense of security because of solid short-term financial performance: one needs to change shoes while they are still comfortable but before they wear out

- Believe that past performance is indicative of future results

- Have incentives that discourage deviation from the current path

- Focus so closely on short-term performance that the company neglects long-term competitiveness

- Be led by individuals who are stronger at executing within existing models than at building new ones

- Rely too heavily on feedback from currently satisfied customers whose allegiance may shift when a better product comes along

- Wait too long—until evidence of the necessity for change becomes definitive—to act

- Make all the right moves but do so insufficiently, allowing existing power structures to monopolize resources and preventing new ideas from being scaled

- Want to change but find that it is trapped by ongoing structures, processes, and initiatives that are complex and difficult to alter

The fact that it is difficult and uncommon for successful companies to turn themselves around preemptively is, however, no argument against its necessity and possibility!

Some companies do, in fact, manage to do so, maintaining performance over a long period of time in the face of external shifts or disruptions and without the need for risky, quantum-leap transformation initiatives. We studied several disruption-prone industries—industrial goods, consumer discretionary goods, IT, health care, telecommunications, and financial services—from 1980 to 2013. And we identified a number of companies that, challenges notwithstanding, managed to generate relatively stable long-term returns. What was their secret sauce?

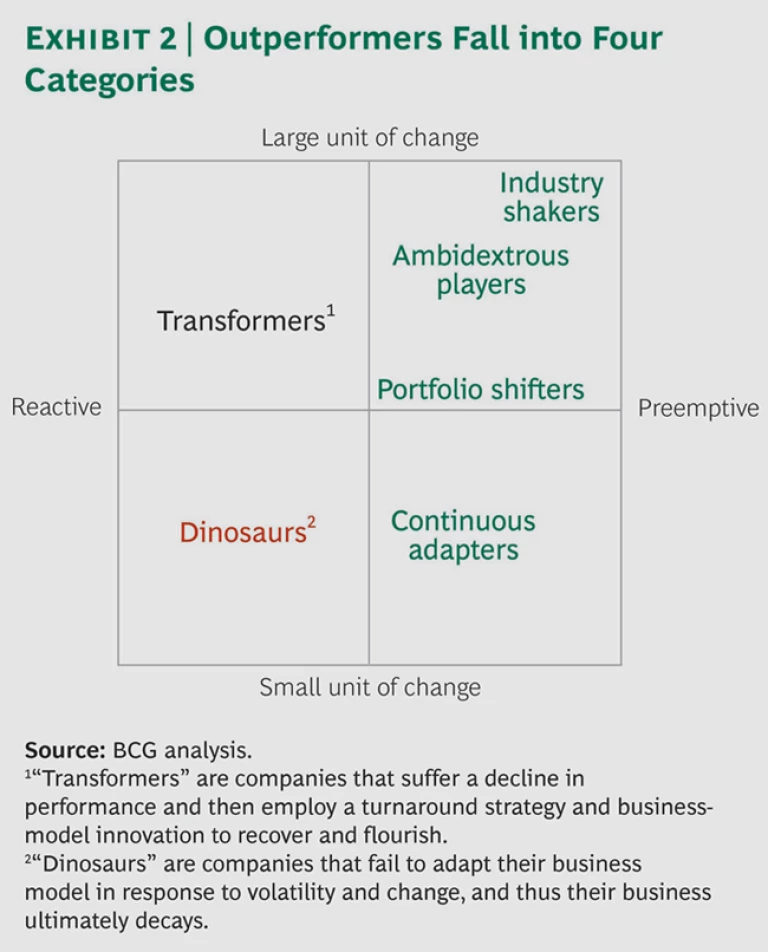

These businesses possessed several distinct sets of attributes and orientations that drove their preemptive adjustment and resulting impressive performance. We grouped the companies into four categories:

-

Continuous Adapters. These companies constantly evolve their business model by making many small changes. McDonald’s, for example, successfully rode the baby boom of the 1960s and leveraged the swelling ranks of teenagers and women in the labor force by providing convenience and an inexpensive, selection-rich menu. In the 1970s and 1980s, the company harnessed the globalization megatrend to expand its footprint internationally, successfully deploying its U.S. model in countries around the world.

Today McDonald’s continues to evolve. It adjusts its product portfolio to reflect new trends and consumer preferences—for example, “fast” and “convenient” are now increasingly augmented by “healthy” and “natural.” The company also creates new formats, such as cafeterias in Europe and high-end coffee chains in the U.S., to address competitive threats. And it is accelerating the speed with which it adapts to the social contexts of the countries in which it has a presence by franchising to locals. This continuous reshaping has persisted even in the face of internal crises, such as when two CEOs sadly passed away in quick succession in the first few years of the 2000s.

-

Ambidextrous Players. A company in this category maintains a balance between exploitation of existing strengths and exploration, even after it has found a successful model. Family succession in public companies is rare; for it to succeed is rarer still. But digital-technology and chip company Qualcomm, led by Paul Jacobs, son of founder Irwin Jacobs, has steadily performed despite massive shifts in telecommunications standards and technologies.

Qualcomm consistently achieves its mission—“to continue to deliver the world’s most innovative wireless solutions”—through a business model that uses returns from past successes (including wins in WCDMA, CDMA, and 3G chips) to fuel future ones (such as in

LTE). Though most of Qualcomm’s revenue comes from chip sales, its mobile-technology licenses provide the company with steady and consistent cash flow that allows it to fund breakthrough R&D and invest in strategic partnerships through Qualcomm Ventures, the company’s venture-capital business unit. Qualcomm reaps benefits from both scale and the drive to continuously search for and build the next big thing in wireless. -

Industry Shakers. These companies seek to drive industry-level change rather than become victims of it. A headline in The New York Times on October 21, 2013, boomed “Sales Are Colossal, Shares Are Soaring. All Amazon Is Missing Is a Profit.” Yet because CEO Jeff Bezos so actively commits to a long-term view and has repeatedly delivered disruptive innovation, investors treat Amazon like a blue-chip stock. Indeed, Amazon continually generates razor-thin profits precisely because it continually reinvests in its future—in refrigerated warehouses for groceries, in same-day delivery in urban centers, and in data servers and analytics, for example.

Bezos founded Amazon in 1994 with a vision that e-commerce would fundamentally disrupt retailing. He chose books as his initial product focus because demand was large, prices were relatively low, and the range of selection was enormous—a combination he deemed ideally suited to the online channel. His foray was so disruptive to the book-selling industry that many brick-and-mortar retailers ultimately capitulated and chose to sell their wares through Amazon’s online storefront, allowing the company to leverage its first-mover advantages in supply chain innovation, product selection, and the setting of platform standards. But Amazon did not rest on its laurels. It self-disrupted its book business with the launch of its e-reader, the Kindle, in 2007; by 2011, the company was selling more e-books than print copies.

What’s next? Amazon continues to succeed by combining its ability to recognize and position itself optimally to leverage nascent long-term trends with its ability to create and set standards for new markets.

-

Portfolio Shifters. A company of this type runs a portfolio of businesses and actively adjusts its emphasis over time. Industrial conglomerate 3M, for example, has more than 35 business units divided among six (through 2012) reporting segments. While the sales contribution by segment has not changed dramatically over time—the company’s Industrial and Transportation segment, for example, contributed 34.6 percent of the company’s overall sales in 2012, compared with 27.4 percent in 2003—the underlying portfolio companies and products have.

3M’s approach to strategic acquisitions and divestments reflects the evolving demand landscape. The company makes acquisitions in anticipation of future growth trends—such as its purchase of Cogent Systems, a manufacturer of automated fingerprint-identification systems, in 2010—and it spun off its print film division in 1996 in advance of the rise of digital imaging. This shifting mix, combined with tight financial management, has allowed the firm, remarkably, to increase dividend payouts to shareholders on an annual basis for the past 55 years, and it keeps operating margins well above 20 percent.

Most important, these steady performers have not achieved consistent success by staying the same. (See Exhibit 2, which contrasts these companies’ orientations with those of two types of more reactive, and ultimately far less successful, businesses: transformers and dinosaurs.) Their distinct approaches to remaining dynamic draw on a common menu of elements:

- An External Orientation. They actively strive to pick up change signals from the outside environment and act upon them.

- A Long-Term Perspective. They focus on sustainable competitiveness rather than on short-term financial results alone.

- Ambidexterity. They have a balanced emphasis on exploitation and exploration.

- Adaptiveness. They constantly adjust their strategy and organization to changes in the external environment and seek to uncover new possibilities through experimentation.

- A Disruptive Mentality. They have a drive to disrupt both the external environment and their own business and are prepared to be disrupted themselves.

- A Healthy Paranoia. They have a lack of hubris and are constantly aware of their competitive vulnerability, independent of their current financial performance.

- Resource Fluidity. They have the ability and willingness to shift resources smoothly across the portfolio and organization, and they do not shy away from promptly exiting eroding but still functioning elements of the business.

- A Constant Focus on Simplicity. They avoid buildups of complexity and rigidity.

Leaders of all enterprises today need to look beyond short-term financial performance, watch for potential disruptions and shifts, and then preemptively address them. They need to be prepared to disrupt to avoid finding themselves victims of disruption. They need to address the imperatives of simplicity, adaptiveness, and business model innovation. In short, successful companies can only perpetuate their successes through continuous preemptive renewal.