Overview

After five years of growth, the banking industry has stalled on the road to recovery. The growth of banks’ economic profit—that is, profit adjusted for risk costs—has weakened on a globally averaged basis for the first time in half a decade.

Conditions that have eroded bank performance include persistently low interest rates, increased competition, digital disruption, and steadily rising operating costs. Waves of new and revised global and local regulations, as well as regulatory scrutiny, have also undercut banks’ economic profit, according to BCG’s latest research.

The goal of our annual study is to provide a comprehensive measure of the financial health of the banking sector in this era of heightened regulation. The report begins by assessing the recent performance of banks in the context of risk, both globally and by region. The second section provides a playbook of regulatory hot-topic issues and implementation challenges that banks must prioritize and master in the short term. The third and final section discusses the four elements of a proactive agenda for chief risk officers (CROs). Such an agenda allows them to perform their current tasks more effectively and efficiently as they transform the risk function’s role beyond regulatory compliance to more direct support of their bank’s business growth.

An assessment of bank results by region found that performance remains strongly divergent nearly a decade after the global financial crisis. European banks continue their struggle to recover, burdened by high volumes of nonperforming loans that remain on their balance sheets. In North America, weaker results among previously top-performing banks pushed the region’s overall performance lower.

Risk-adjusted profit also took a hit in Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, and Africa. Only in South America did bank performance rise strongly, rebounding from a sharp decline in the prior year.

The twists and turns of regulatory change and oversight show no signs of receding. The flood of revisions averages 200 per day—three times the rate in 2011. Global banks must diligently monitor and implement change in three regulatory clusters: financial stability, prudent operations, and resolution.

Forward-looking CROs at successful banks will master this regulatory matrix as part of a broader plan to transform the capabilities and the role of their bank’s risk function. The four-part agenda calls for digitizing the risk function and elevating its knowledge and data resources with cutting-edge technologies. Banks can achieve those goals by adopting new, potentially disruptive technical capabilities and services, and by collaborating with regtechs and other fintech enterprises.

The resulting transformation of risk management will add substantial value by allowing the function to contribute actively to the bank’s commercial growth and customer relations. More broadly, that elevated role will support the shared concerns and interests of banks, investors, and regulators alike: to ensure the industry’s ongoing viability, profitability, and growth, as well as to strengthen its prospects for attracting equity, while maintaining adequate capital levels and avoiding future speculative crises.

The Global Banking Recovery Stalls

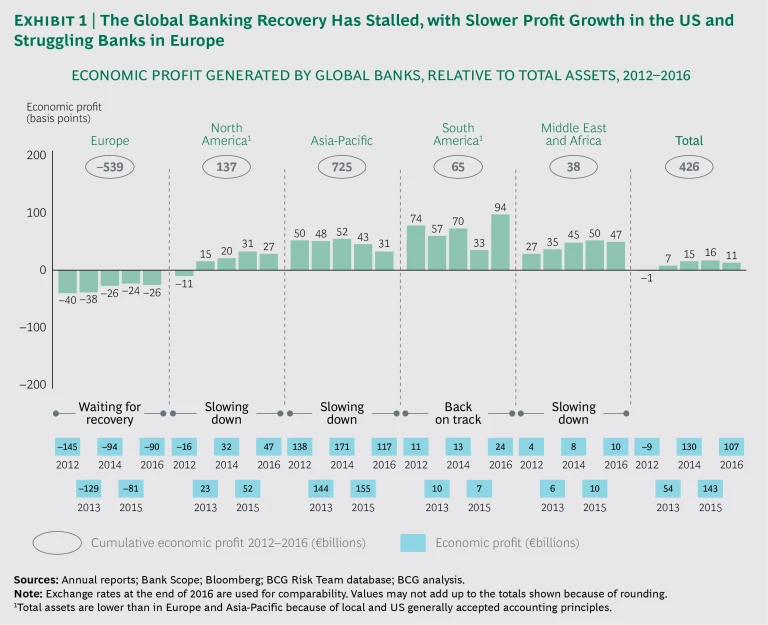

The economic recovery of the banking industry has stalled following five consecutive years of improvement in the aftermath of the 2007–2008 financial crisis. (See Exhibit 1.) While banking remains a profitable sector overall, the growth of profit adjusted for risk costs, or economic profit (EP), has slowed.

Bank results by region remain strongly divergent. Banks in North America are profitable, though EP has weakened, but European banks still struggle to recover nearly a decade after the crisis.

In 2016, EP weakened on a globally averaged basis for the first time in half a decade.

These are among the findings of The Boston Consulting Group’s eighth annual study of the overall health and performance of the global banking industry. BCG’s study assessed the EP generated from 2012 through 2016 by more than 350 retail, commercial, and investment banks, covering more than 80% of the global banking market. EP—which weighs refinancing, operating, and risk costs against income—provides a comprehensive measure of bank financial health in an era of ongoing regulatory changes.

Economic Profitability Varies Widely by Region

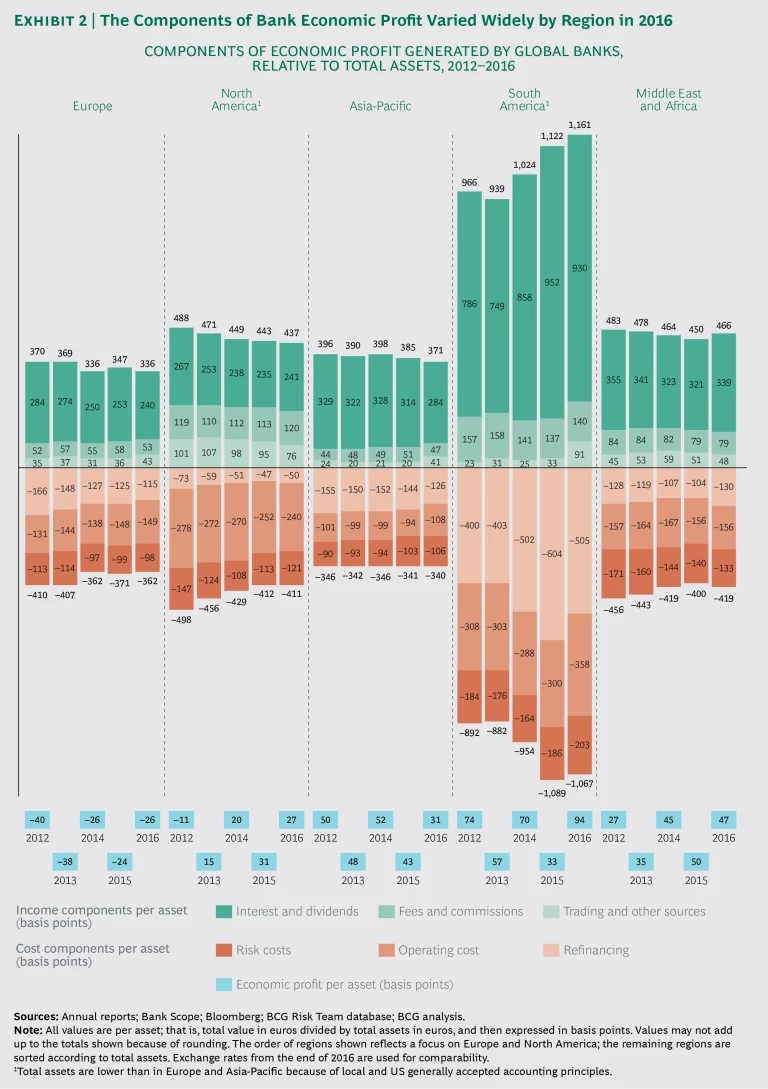

As in previous years, the economic performance of banks varied considerably among regions and among banks in each region. (See Exhibit 2.)

In Europe, bank balance sheets remained mired in nonperforming loans (NPLs) in 2016, keeping risk costs high. Banks continued to struggle with low net interest and fee income, only partly offset by a slight increase in trading income. Operating and risk costs remained roughly constant. The result was negative EP (–26 basis points), meaning that banks could not earn their cost of capital. The range of EP, however, shifted slightly upward, as results improved for both top and bottom performers.

North American banks registered their first annual decline in EP since the financial crisis, interrupting what had been a continuous recovery. The relatively small dip in overall performance from an EP of 31 basis points in 2015 to 27 basis points in 2016 was largely driven by the weaker results of previously top-performing banks, as lower performers narrowed the gap. A slight increase in net interest and commission income almost offset the sharp drop of 19 basis points in trading income, while overall cost components remained constant.

Banks in Asia-Pacific have now registered a significant two-year decline in EP, from 52 basis points in 2014 to 31 basis points in 2016—the lowest value in five years. The decline was largely due to falling net interest and dividend income. Increased operating and risk costs also took a toll, notably in the form of higher provisioning costs at large Indian banks because of stricter local regulatory requirements. Nonetheless, the region’s performance outshone that of both Europe and North America.

South American banks recovered strongly in 2016 after a sharp decline in 2015, as EP rose from 33 basis points to 94. In large part, the increase resulted from growing net interest and trading income, overcoming an escalation in operating costs from 300 basis points to 358.

Bank performance in the Middle East and Africa, after improving for several years, dipped from 50 basis points in 2015 to 47 in 2016. Nevertheless, it remained positive, although net interest income fell.

A Shared Interest of Banks, Regulators, and Investors

These variations and abrupt shifts in regional performance reflect the array of harsh challenges facing banks today in both mature and developing markets. Two of the most critical challenges—one of them global and the other most pronounced in Europe—highlight the fact that banks, regulators, and investors share a fundamental interest in identifying solutions.

The global challenge is an existential one: to protect the industry’s ongoing viability and prosperity in a volatile, low-interest, and intensely regulated environment. The need to maintain a profitable but well-regulated banking sector is critical for investors and regulators alike. Both parties want to ensure prospects for growth and attract equity while maintaining adequate capital levels and avoiding future speculative crises.

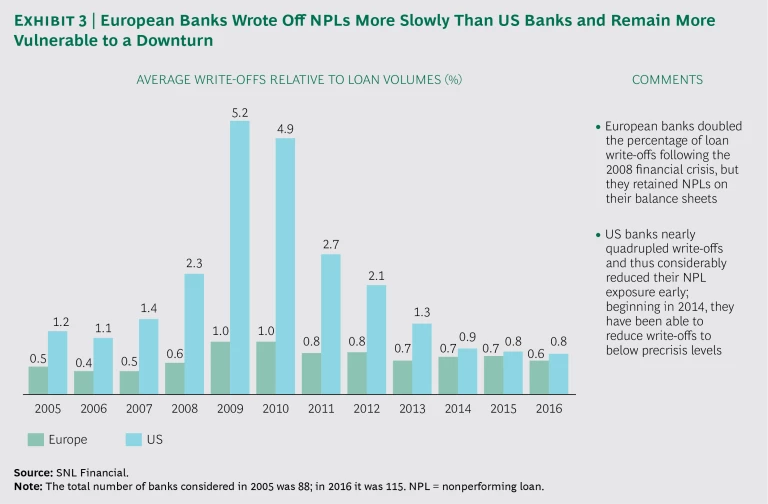

The challenge raising the most concern in Europe involves finding a means to shed the crushing weight of NPLs on bank balance sheets and earnings. If the low-interest-rate environment remains uncorrected, this legacy of the financial crisis could persist for years.

For example, whereas European banks doubled loan write-offs following the crisis, US banks nearly quadrupled write-offs during that period, moving much more quickly to reduce their NPL exposure and strengthen their balance sheets. As a result, US banks are now more resistant to future crises; but European banks, in contrast, continue to be more vulnerable than their American counterparts to economic downturns. (See Exhibit 3.)

But shared concerns alone won’t create common solutions, just as stricter capital ratios required by regulators won’t provide the higher returns on equity demanded by shareholders. Each bank must build its own path to success, balancing regulatory compliance and operational efficiency. That will require a disciplined approach and a method of bank steering that strategically uses regulatory processes and tools.

Mastering the Matrix of Regulatory Change

It is essential for banks to master the complex global matrix of regulatory changes. The broad elements of most top-level regulatory reform packages are already established. Yet banks still face the burden of actually implementing those requirements while adapting their processes to remain efficient.

Meanwhile, the flow of individual regulatory revisions that global banks must track remains high, averaging 200 revisions per day worldwide.

Bankers in Europe expect a convergence of national regulations, driven by increased European Central Bank (ECB) attention to issues previously in the domain of national regulators. At the same time, business models will be put to the test in a banking system that has apparent overcapacity and that must cope with strong pressure on capital levels from the heavy burden of NPLs.

In the US, some degree of banking deregulation is likely to occur, but its extent and pace remain unclear. The House of Representatives has approved one measure—the Financial Choice Act of 2017—but that measure has faced tougher opposition in the Senate. The bill, if enacted as proposed, would roll back many of the provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act. For example, it would ease the regulatory regime for well-capitalized banks, repeal the Volcker rule, and introduce more than two dozen regulatory-relief measures for community financial institutions.

The regulatory approaches taken outside Europe and the US in smaller markets—some of them regional or developing markets—will often depend on the initiatives of regulators in the mature markets. Smaller markets have fewer regulatory resources and, in any case, will generally confront the same cluster of regulatory issues. In addition, broad global regulatory changes focus on the activities of the large, global banks and other financial institutions that were at the heart of the global financial crisis. Regulation of these institutions’ activities at home will be a prerequisite and will establish the context for regulation elsewhere.

Three Clusters of Global Regulation

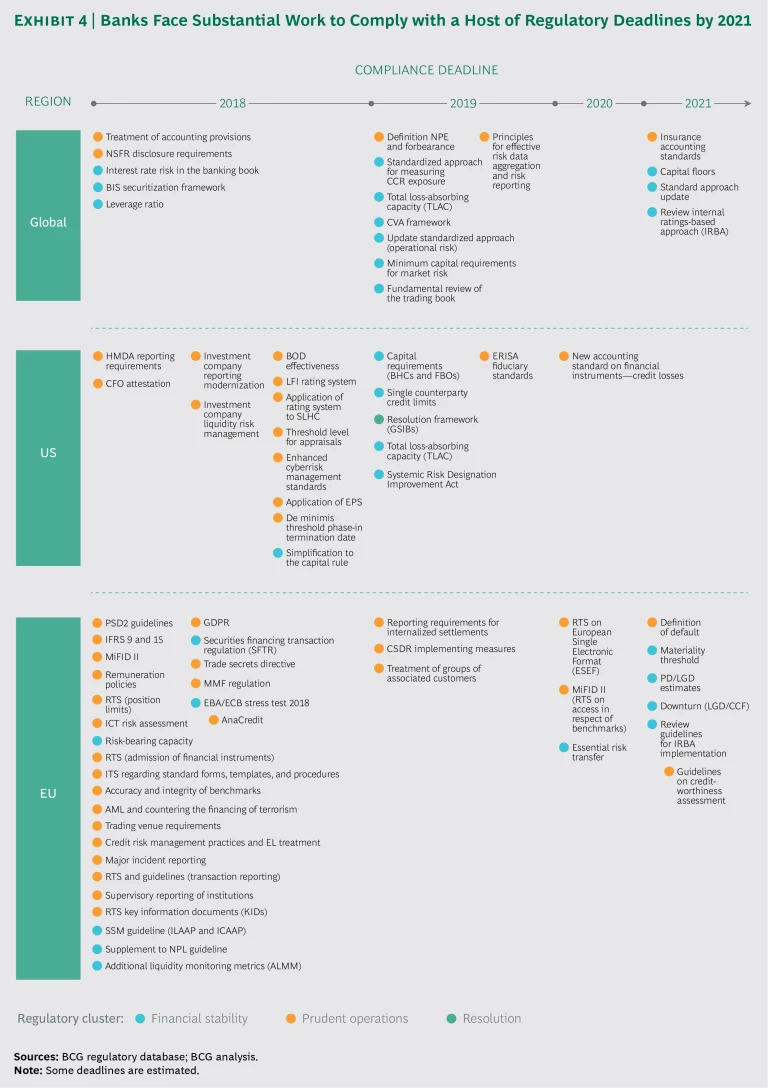

An overview of global regulatory initiatives that impose a deadline of 2021 for implementation and compliance shows that banks face a substantial burden of work in the near term. (See Exhibit 4.)

To assess the current status and impact of these regulations, we have organized the global regulatory spectrum into three clusters: financial stability, prudent operations, and resolution.

Financial Stability

Financial stability is the most advanced regulatory area, although several details continue to evolve. Both the Basel IV reform package and the introduction of IFRS 9 put pressure on capital levels. Regulators continue to focus on risk-based capital requirements, but they also aim to improve model results. The ECB’s targeted review of internal models (TRIM), which must be finalized by the end of 2019, focuses on the consistency of such model results across banks. The ECB has also issued guidelines for the treatment of NPLs, given the spotlight on them in Europe. The guidelines include a provisioning backstop that forces banks to fully provision unsecured loans after two years in default and secured loans after seven years in default.

In December 2017, the Basel Committee published the final Basel III revisions, clarifying a number of open points. One revision increased the robustness and risk sensitivity of standardized approaches to credit risk, credit valuation adjustment (CVA) risk, and operational risk. A second revision constrained the use of internal models under the institutional review board’s approach for credit risk and removed the use of internal models for CVA risk and operational risk. The committee also introduced a leverage ratio buffer to further limit the leverage of global systemically important banks. Finally, they replaced the existing Basel II output floor with a risk-sensitive floor of 72.5%, based on the revised standardized approaches. The floor will primarily affect banks whose extensive use of internal models results in a risk weight lower than that of standardized approaches. In particular, the floor can lead to risk-weighted asset (RWA) increases exceeding 20%—especially for Germany, France, Benelux, and the Nordic countries—mainly driven by significant RWA increases for mortgages.

In addition to having met the requirements of these Basel III revisions, affected banks must have implemented IFRS 9 by January 2018, and that obligation will also have an impact on capital ratios. The primary purpose of the increased capital requirements is to account for the full, fair value of volatile or troubled assets, such as in shipping finance and rundown portfolios, as well as to cover a lifetime expected loss for subperforming loans (the gray book). An impact analysis conducted by the European Banking Authority (EBA) has established that the average capital impact of IFRS 9 on common equity Tier 1 ratios is 59 basis points.

Stress testing, another pillar of financial stability, has also advanced quickly. In the US, stress testing is an established annual exercise that is done via the comprehensive capital analysis and review (CCAR) and the comprehensive liquidity analysis and review (CLAR). In Europe, the EBA stress test and the requirements of the internal capital adequacy assessment process (ICAAP) and the internal liquidity adequacy assessment process (ILAAP) cover this topic. The EBA stress test is performed on an irregular basis, but the bar rises steadily. In 2018, the adverse scenario will be the most severe to date, implying a deviation of EU GDP from its baseline level by 8.3% in 2020. The new rule on EU intermediate holding companies (IHCs), which will be part of the next version of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR II), will require EU IHCs to be separately capitalized. That revision mirrors the guidance of the US enhanced prudential standards.

Stress testing, another pillar of financial stability, has also advanced quickly.

Another issue involving the financial stability of Europe’s banking market is the impact of Brexit. A “hard” Brexit scenario, in which the UK loses member-level access to the EU market and most of its presence there, could substantially shift Europe’s banking landscape for a number of products and customer groups. Since the deadline for Brexit is the end of March 2019, time is short for banks to decide on their approaches, location choices, and business models.

Prudent Operations

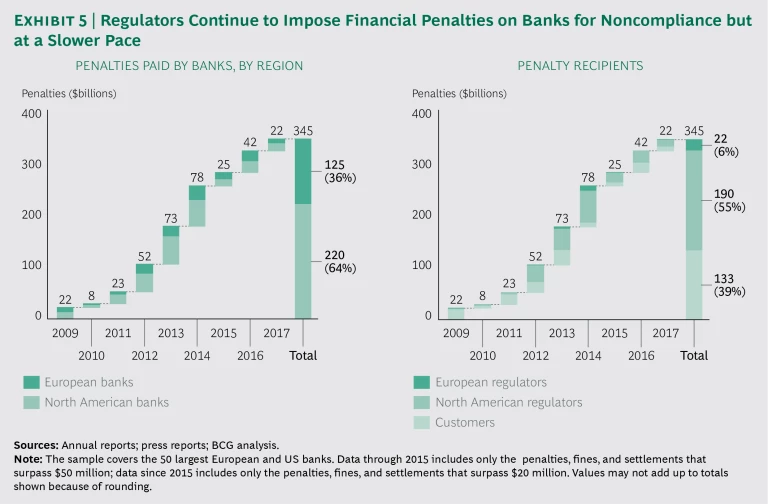

Strict penalization for regulatory noncompliance continues. Cumulative penalties imposed since 2009 rose to $345 billion by the end of 2017, an increase of $22 billion from the cumulative total at the end of 2016. (See Exhibit 5.) But this was a slowdown compared with previous years. US regulators continued to dominate the issuance of penalties in 2017 as they did in 2016. European regulators don’t seem fully operational yet in this regard. However, their inaction may represent the quiet before the storm. Most of the 2017 penalties related to instances of mis-selling and improper conduct that had occurred in years past.

Enhanced financial integrity standards under the Markets in Financial Institutions Directive II (MiFID II) and the capital markets union, once in place, will usher in a new era of market transparency, bolstered by requirements for more-frequent and higher-quality internal reporting. As the roles and specialization of EU regulators evolve, banks will face rising pressure to ensure stable compliance processes and adequate controls, such as for outsourced tasks. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which banks must implement by May 2018, requires banks to establish robust processes to safeguard the data of both customers and employees, and to disclose any data breach. The burden on banks imposed by the GDPR will grow as digitization accelerates, necessitating comprehensive measures to protect expanding volumes of client and internal transaction information used for modeling and process optimization.

Resolution

Resolution efforts remain the least developed area of reform, particularly in Europe. Effective resolution requires a bank to have an established plan, or “living will,” that details its strategy for rapid and orderly restructuring in the event of material financial distress or failure. The goal is to safeguard the public interest and avoid disruption of the financial system, without having to resort to the taxpayer bailouts employed in past financial crises.

The process of effective resolution planning is both complex and comprehensive. It requires banks to develop an in-depth and hypothetical understanding of their overall organization, core businesses, and financial and operational capacity and risks, and then develop a restructuring plan that takes into account an array of supervisory jurisdictions and legal frameworks.

In the US, despite delays, the submission of resolution plans to the Federal Reserve Bank is now an established process. Eight leading banks have received an extra year, until 2019, to submit living wills. In Europe, however, progress toward resolution has lagged. The main achievement there has been the establishment of depositor preference over unsecured funding both for resolution and bankruptcy proceedings. In addition, minimum standards for capital and “bail-in-able” debt have been established on the basis of the minimum requirements for eligible liabilities, in order to ensure sufficient capital in case of required bail-ins of equity investors. The single resolution mechanism (SRM) is now in place to address instances of bank failure. The SRM has been used only once to date, in the case of Banco Popular in Spain. Other cases, such as Banca Popolare di Vicenza and Veneto Banca, were solved nationally without SRM involvement.

European regulators have ended efforts to agree on regulations that would cover bank separation, citing lack of consensus among member states.

The Savvy CRO’s Agenda for Optimizing Risk Management

The future success of risk management for banks will depend in large part on the ability of the chief risk officer (CRO) to transform the risk function. The emphasis should shift from playing a purely functional business-support role to becoming a proactive source of enhanced decision making and assistance for the bank’s commercial opportunities, in partnership with executive management. Modern CROs are becoming differentiators by assuming active roles in optimizing risk-return profiles and steering the deployment of scarce resources.

Staying in control of compliance with shifting regulations will remain critical to success. CROs can achieve this goal—while positioning risk management capabilities to add value for the whole bank—by establishing an agenda with four priorities:

- Continue to pursue a strategic program to monitor and manage compliance with the matrix of changing global and local regulations and detect new emerging risks.

- Expand and leverage the risk function’s data and analytics capabilities in order to enhance the bank’s internal decision making and to extend commercial opportunities and client service.

- Digitize the bank’s risk management function.

- Adopt cutting-edge technologies through collaboration with regtechs and other fintech firms.

When approached with discipline and insight, each of these actions can yield strong benefits.

A Strategic Program Ensuring Full Regulatory Compliance

The basis for ensuring regulatory compliance, as discussed in the previous section, lies in the CRO’s mandate to retain mastery of the regulatory project portfolio. Staying abreast of the regulatory agenda and managing traditional risk types—such as for credit, market, operational risk, and compliance risk—is crucial. But it is not enough. CROs must also identify and manage new types of risk, in categories such as cybersecurity and data protection.

Make Risk Management a Source of Competitive Value

Forward-looking CROs are reinventing the risk function’s knowledge and data resources, as well as its capabilities, to help the department become a source of competitive value. They can establish this enhanced role by partnering with the bank’s business units in at least three ways:

- Make critical and timely decisions on financial risks through an integrated view of balance sheet resources to achieve optimal risk-return tradeoffs.

- Develop a managerial view of nonfinancial risks, and use fact-based risk assessment methodology to prioritize the allocation of internal resources.

- Deploy the risk function’s capabilities and data to support decision making by the bank’s commercial clients, and develop new advisory services and dedicated tools for those clients.

Each of these three paths for deriving added value from the risk function provides distinct competitive benefits for the bank and services for its clients.

Integrated Balance Sheet Management. The impact of regulatory change on bank business models underscores the need for an organization-wide view of resource consumption across the enterprise. This requires linking key balance sheet and regulatory ratios with the P&L view and its management. The risk function can partner with treasury, finance, and the business units in three ways to develop an integrated balance sheet management framework:

- Exploit the risk function’s rich information resources and rigorous modeling methodologies to produce advanced metrics on capital, liquidity, and funding consumption.

- Use scenario simulation capabilities to develop advanced managerial decision-making tools.

- Identify and quantify managerial initiatives to jointly optimize capital, liquidity, funding, IFRS 9 provisions, and leverage.

An integrated balance sheet view is possible when risk, treasury, and business units work together to shift from a siloed, risk-by-risk or business-unit perspective to an integrated view by client or sector across the entire bank. That common vantage allows assessment of all organizational impacts within the same model, which is the key to determining best risk-return tradeoffs.

The recent evolution of stress-testing frameworks now calls for an alignment of stress tests with internal business planning—for example, by including different forecasting scenarios. By adopting this type of integrated view as a managerial tool, banks can transform stress testing from an expensive regulatory exercise into an effective steering instrument for the bank.

Nonfinancial Risk Assessment. Banks must increasingly cope with the impact of nonfinancial risks, such as those associated with data protection, cybersecurity, market abuse, and anti-money-laundering. Top executives and boards need a structured, fact-based view of risks in order to define relevant actions such as strengthening control systems and enhancing monitoring in areas with high levels of risk and inadequate control systems. Such a view also serves as a tool to optimize resource allocation and simplify the control framework. In BCG’s experience with client projects in multiple industries, cost reduction measures typically lie outside the risk and compliance functions. For example, we have found optimization potential within the business units (in connection with client data protection), within operations (through a reduction in manual activities in the front and back office), and in IT (via system changes necessitated by MiFID II best execution requirements).

Top executives and boards need a structured, fact-based view of risks in order to define relevant actions.

End-Customer Risk-Based Advisory Offerings. Risk management’s expertise in identifying, assessing, and monitoring risk exposure can be transformed into a revenue stream through commercial offerings to the bank’s clients. An example is to provide a risk-advisory or rating-advisory service for small and midsize corporate clients, in collaboration with the bank’s customer-facing front office. Such services can offer the client transparency into the main drivers of its credit rating. Similarly, hedging-needs advisory services can help clients identify market exposures and devise appropriate hedging solutions. Creating advisory products can strengthen the partnership between risk management and the bank’s business units by putting risk’s strong internal assets to work for the client.

Digitize the Risk Function

Digitization—now a crucial component of banking strategy—is transforming the way banks do business. Various forms of digital innovation now support almost all activities. As digitization redefines customer journeys and experiences, core processes, including risk management, must follow.

Risk functions have been leaders in adopting and deploying a handful of innovative technologies relevant to their role, such as modeling and data use. But they have been less quick to use rapidly evolving digital technologies to support core risk management processes.

Digital transformation can create significant value by making processes more efficient.

The full multicourse menu for digitizing risk functions is long. (See the sidebar.) Yet only a few technologies may be useful to each bank in its individual journey. Bank CROs need to find the best approach to start this journey now, instead of relying on traditional, linear test-and-learn approaches, because of the high potential cost of errors in the risk function compared with the launch of a minimum viable product at the customer interface.

How Banks Reap Rewards by Digitizing Risk Management

Digitizing a bank’s risk function differs from digitizing the front office. But the effort can be quite rewarding. A customer-facing front office may harness digital technologies to improve the customer journey and experience. In the risk function, digitizing can improve process efficiency and effectiveness. But the multicourse menu for digitizing risk and compliance functions is long, with many entry points along the banking value chain. The following examples, drawn from BCG client projects, illustrate just a few of the technologies that banks can implement with meaningful results:

- Machine learning boosts efficiency of money-laundering detection. The standard approach that banks use to detect money-laundering cases applies simple rules to automatically create alerts for potential incidents. Those cases are then checked manually. Applying pattern-matching techniques that used machine learning based on an analysis of a historical sample of data from about 80 million transactions yielded an improved approach. The new methodology significantly reduces the number of false positives, which, in turn, reduces the amount of manual work required by 70% to 90%.

- Dynamic credit scoring improves the small-business early-warning process. Instead of using a single approach to review each client in the portfolio, a bank scored small-business clients dynamically on a monthly basis, using transactional data. Then it used a traffic light system to classify each client: clients categorized as “green,” for instance, received only a light review, while those tagged as “red” were reviewed in much greater detail. As a result, the efficiency of the annual review process for small-business clients increased by 20% to 25%.

- Automated ratings speed credit processing for small- and midsize-business customers. Traditional credit processing, even for existing clients, required a complicated flurry of interactions and document exchanges between a bank and its customer. The bank replaced this process with an automated rating system that gives weight to account behavior data and credit bureau data. The new system offers an automated and accelerated credit decision, up to a determined maximum loan volume per customer. The result: an average reduction of 75% in processing time for loan applications, and many fewer interactions required among the customer, the relationship manager, and the risk function.

Quantification of potential benefits and costs is part of the design. Effectiveness can be strengthened not only by greater transparency achieved through better decisions or automated regulatory reporting, but also by the improved accuracy of model outputs as a result of the better use of big data.

Digital transformation can also create significant value by making processes more efficient. It can, for example, lower costs by 25% or more in end-to-end credit processes and in reduced operational risk through increased automation and analytics.

For each process, use cases for digitization are quickly emerging. Customer on-boarding, for instance, is one process that financial institutions must constantly adapt to the ways customers interact with them, taking into account a multichannel approach reflecting the central role of the smartphone in everyday life. Model life cycle (MLC) management is another example. As banks face challenges related to the use of increasingly complex models in the banking value chain, MLC allows them to automate the end-to-end process of model development, documentation, validation, and usage tracking.

Digitization requires transforming the risk function’s operating model, its role within the bank, and its resource allocation. Taking five actions can support this transformation:

- Shift some pure production tasks, such as reporting on the basis of pure business data, to the business units in the first line of defense or to shared service centers.

- Strengthen the oversight and risk anticipation capabilities in the risk function.

- Implement smart technologies to significantly cut costs and increase effectiveness.

- Employ new ways of working, such as agile.

- Adjust the bank’s culture, along with individual skill sets, to promote value creation and thought partnership for the business.

Collaborate with Regtechs for Innovation and Advantage

Regtechs and other fintech companies form a rapidly expanding universe of potential bank allies—and competitors—that successful CROs must get to know and understand.

Regtechs are gaining momentum as potential partners in boosting innovation and advantage in bank risk capabilities. Many offer digital innovations and efficiencies for banks in completing compliance, reporting, and other risk management and regulatory tasks.

At the same time, banks must of course remain prudent about the risks involved in delegating important regulatory or compliance tasks to a third party. The CRO must strike the right balance between creating value for the business and avoiding potential risk and complexity in implementing digital innovations and services offered by regtechs.

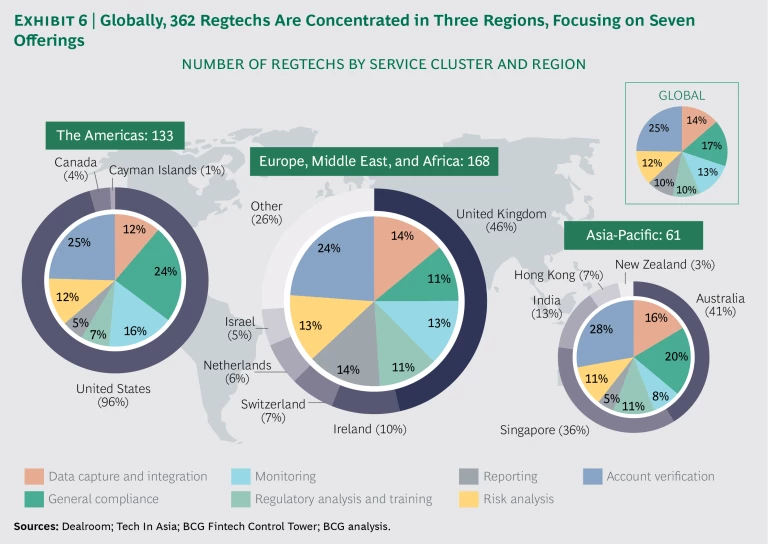

BCG’s data and research platform Fintech Control Tower tracks thousands of fintech companies. This category of companies includes an expanding subset of more than 360 regtechs worldwide that specialize in services related to regulatory tasks. (See Exhibit 6.)

Two factors have fueled regtech growth: the increasing number and complexity of regulatory requirements and the ability of regtechs to deploy emerging new technologies that are more efficient or effective in fulfilling such regulatory requirements. Those technologies typically include artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data techniques; blockchain and biometrics are also common, although their use is still evolving.

Regtech companies are concentrated in three markets. About 130 operate in the US, 80 in the UK, and 25 in Australia. Their offerings focus on seven service clusters: data capture and integration, general compliance, monitoring, regulatory analysis and training, reporting, risk analysis, and account verification. Verification alone accounts for 25% of all regtech offerings.

The range of regtech use cases varies. The early benefits of using regtechs predominantly arose from their ability to help banks to scale and comply more efficiently with increasing regulatory burdens. Other benefits now include achieving improved risk management and regulatory compliance outcomes. Increasingly, regtechs also provide a better digital experience for clients. They create business opportunities by eradicating long, complicated manual processes and by supporting the view that the compliance function can help enhance revenues in financial services.

Among banks, current use cases include the following:

- Reducing manual workflow in know-your-customer processes

- Monitoring both anti-money-laundering (AML) initiatives and countering the financing of terrorism (CFT) efforts, in order to reduce false positives

- Integrating data across the organization

- Rapidly identifying regulatory changes

Regulators, many of which use regtech services, typically do not supervise bank use of regtech solutions. To date, they have limited their interaction to observing and building expertise in the regtech ecosystem, providing regulatory guidance to the industry through white papers, and partnering with regtechs and financial institutions to develop the infrastructure necessary for implementation of regulations.

At the same time, many regulators express strong interest in the potential of applying regtech solutions to AML initiatives and CFT efforts.

Bank engagement with regtechs is on the rise, despite general concerns in management and the perception among compliance and risk teams that the rewards might not outweigh the risks of engaging a regtech. The rewards for innovation are unclear and must be balanced against the risk of costly failures when implementing change. Banks must also manage the outsourcing risk of delegating certain tasks to a third-party provider, along with the cybersecurity risks linked to the exchange of data between a bank and a regtech.

The bottom line, however, is that regtechs will probably continue to gain importance—and a more clearly defined role—in the global banking ecosystem. The forward-thinking CRO will pursue sophisticated and growing collaborations that support the long-term transformation of risk management into an innovative source of value creation at the heart of bank management.