M&A is tough, especially when it involves an underperforming asset that needs a turnaround. About 40% of all deals, on average, require some kind of turnaround, whether because of minor problems or a full-blown crisis. With M&A valuations now at record levels, companies must pay higher prices simply to get a deal done. In this environment, leaders need a highly structured approach to put the odds in their favor.

The greatest M&A turnarounds

The greatest M&A turnarounds

- Automotive: Groupe PSA + Opel

- Biopharmaceuticals: Sanofi + Genzyme

- Media: Charter Communications + Time Warner Cable + Bright House Networks

- Industrial Equipment: Konecranes + MHPS

- Retail Grocery: Coop Norge + ICA Norway

- Shipbuilding: Meyer Werft + Turku Shipyard

- Retail: Office Depot + OfficeMax

- Energy: Vistra + Dynegy

We recently analyzed large turnaround deals—those in which the target was at least half the size of the buyer in terms of revenue, with the target’s profitability lagging its industry median by at least 30%. Our key finding was that these deals can be just as successful as smaller deals that don’t require a turnaround in terms of value creation. However, they have a much greater variation in outcomes. In other words, the risks are greater and the potential returns are also greater. Critically, our analysis identified four key factors that lead to success in turnaround deals.

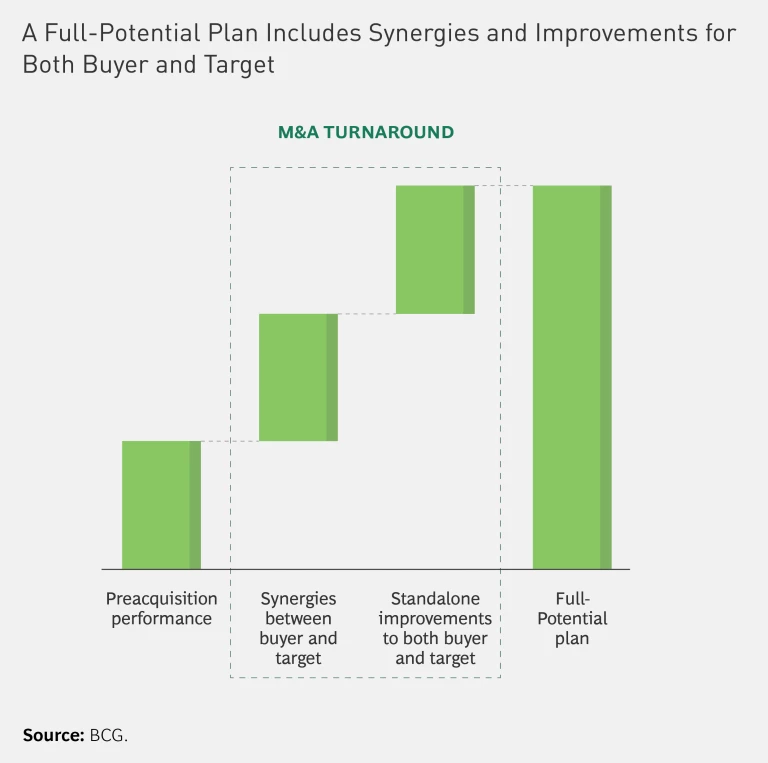

1. These buyers use a “full potential” approach to identify all possible areas of improvement. Rather than merely integrating the target company to capture the most obvious synergies, a full-potential approach generates improvements to the target company, captures all synergies, and capitalizes on the opportunity to make needed upgrades to the acquirer as well. (See the exhibit.)

2. These buyers have a clear rationale for how the deal will create value, and they take a structured, holistic approach:

- They initially fund the journey by generating quick wins that deliver cash to the bottom line quickly, typically restructuring back-end operations to reduce costs and increase efficiency.

- Then they pivot from cost-cutting to growth measures in order to win in the medium term. They revamp the portfolio, selling off some business units and assets and buying others that align with their strategic direction.

- Finally, they invest in the future, often focusing on building digital businesses, upgrading processes with AI, and investing in R&D to secure long-term growth and expanding margins.

Winning buyers have a clear rationale, execute with rigor and speed, and address culture upfront.

3. Successful acquirers execute their plan with rigor and speed. They begin developing plans long before the deal closes, so that they can begin implementation on day one, seamlessly combining the core elements of post-merger integration and a turnaround program. These acquirers are extremely diligent in building clear milestones and objectives into the plan to ensure that key integration and improvement steps are achieved on time. Throughout the process, they move as quickly as possible, regarding speed as their friend. Moreover, they are confident enough to make their targets public and to systematically report on progress.

4. Winning acquirers address culture upfront by reorienting the organization around collaboration, accountability, and bottom-line value. Culture can often be hard to quantify or pin down, but it’s critical in shaping a company’s performance following an acquisition. (See Breaking the Culture Barrier in Postmerger Integrations, BCG Focus, January 2016.)

The case studies on the following pages illustrate these four principles. They offer clear evidence that M&A-based turnarounds may be hard but carry significant opportunity when done right.

Automotive: Groupe PSA + Opel

Groupe PSA, the parent company of Peugeot, Citroën, Vauxhall Motors, and DS Automobiles, was languishing after the 2008 financial crisis. Demand was particularly slow to recover in Europe, which accounted for more than two-thirds of the company’s sales. After losing $5.4 billion in 2012 and $2.5 billion in 2013, Groupe PSA struck a deal to sell 14% of the company to Chinese competitor Dongfeng and another 14% to the French government, for $870 million each. With the capital raised, it launched a turnaround program in 2014. As part of the program, Groupe PSA bought the Opel brand, which had lost about $19 billion since 1999, from General Motors. The deal was finalized in August 2017.

The turnaround has a strong growth element with a focus on strengthening brands. A sales offensive was built on reducing the variety of models available, offering more attractive leases (possible thanks to the company’s stronger financial services capability), and maintaining discount discipline. Cost efficiency is another important element. Limiting the number of models reduces complexity across the combined group, which reduces costs in both manufacturing and R&D. The increased scale across fewer models leads to simpler procurement and more negotiating clout with suppliers.

The turnaround continued at a relentless pace through the first half of 2018, with profitability restored at Opel and margins continuing to rise for Groupe PSA as a whole.

Overall, gross margins have increased by 35% since 2013. During the same period, Groupe PSA has rebounded from losing money to an EBIT margin of 6%, in line with competitors such as General Motors and ahead of Hyundai and Kia. Perhaps most impressive, the company’s market cap has increased more than 700%. In all, the transformation has allowed Groupe PSA to resume its position as one of the top-performing automakers in the world.

Key success factors in this turnaround: Groupe PSA started the turnaround by raising capital to fund the journey. That enabled it to buy GM’s Opel unit, halt steep financial losses quickly, and generate a profit within one year of the acquisition.

Raising capital allowed Groupe PSA to buy GM’s Opel unit and generate a profit within one year.

Biopharmaceuticals: Sanofi + Genzyme

In 2009, French pharmaceutical company Sanofi was in acquisition mode. Many of its products were losing patent protection, and the company wanted to shift from traditional drugs into biologics. One potential target was Genzyme.

From 2000 through 2010, Genzyme had grown rapidly, but manufacturing issues at two of its facilities halted production and led to a shortage of key drugs in its portfolio. Sales plunged, the US Food and Drug Administration issued fines, and investors called for management changes. But many features of the company still met Sanofi’s needs, including a lucrative orphan drug business with no patent cliff and a strong history of innovation. Sanofi made an offer: $20 billion, or $74 per share, which was roughly Genzyme’s value before the manufacturing problems hit.

Management laid out a bold ambition and moved fast. The company streamlined manufacturing, opening a new plant to reduce the drug shortage and simplifying operations to remove bottlenecks at existing plants. Next, it moved sales and marketing for some of Genzyme’s businesses, including oncology, biosurgery, and renal products, under the Sanofi brand. It also reduced the overall sales force by about 2,000 people.

Genzyme’s R&D pipeline was integrated into Sanofi, and a new portfolio review process led to the cessation of some studies and the reprioritizing of others. And about 30% of Genzyme’s cost base was reduced through the integration with Sanofi. Genzyme’s diagnostics unit was sold off, and about 8,000 full-time employees were eliminated in the EU and North America.

The moves generated positive results fast. Overall, the integration led to about $700 million in cost reductions through synergies. By 2011, the company was back in expansion mode with 5% revenue growth, increasing to 17% in 2012. Only about 13% of Sanofi’s revenue came from Genzyme products, but these were poised for strong growth, positioning Sanofi as a global leader in rare-disease therapeutics and spurring its evolution into a dominant player in biologics.

Key success factors in this turnaround: Sanofi laid out a bold ambition in its acquisition of Genzyme, and it executed a strategic repositioning with extreme speed, cutting costs and increasing top-line growth.

Genzyme executed a strategic repositioning with speed, cutting costs and increasing top-line growth.

Media: Charter Communications + Time Warner Cable + Bright House Networks

With 8% of the US market in 2014, cable TV provider Charter Communications found itself facing fierce competition for multichannel video subscribers, who usually had bundled services with increasingly important broadband subscriptions. The threat came not only from other multichannel video providers in its markets—including direct-broadcast satellite services and large telcos—but from internet streaming services, as many cable subscribers were “cutting the cord” and streaming video over mobile and other devices.

To protect its market share and profits, Charter significantly expanded its subscriber base in 2015 by acquiring Time Warner Cable and Bright House Networks, which had a 20.8% and 3.6% share of the US cable market, respectively, paying $67 billion for the two businesses. The acquisitions made Charter the second-largest broadband provider and the third-largest multichannel video provider in the US.

With the deal closed, Charter launched a bold transformation that captured extensive synergies among the three businesses in areas such as overhead, product development, engineering, and IT, and it introduced uniform operating practices, pricing, and packaging. Most important, the company’s increased scale improved its bargaining power with content providers. Charter went beyond synergies in a full-potential plan to accelerate revenue growth, product development, and innovation through the increased scale, improved sales and marketing capabilities, and enhanced cable TV footprint brought about by the combination of the three companies. It improved products and services, centralized pricing decisions, and streamlined operations to achieve additional operating and capital efficiency.

As a result, Charter kept up its premerger growth trend and profitability, growing at an annual rate of 5.5% post-merger to reach $42 billion in revenues in 2017. In addition, Charter’s value creation significantly outperformed that of its peers, increasing annualized TSR to 289% from the closing of the transaction to the end of 2017.

Key success factors in this turnaround: Charter made a bold move in acquiring both Time Warner Cable and Bright House Networks. Management developed an extensive plan to generate operational synergies and rationalize the commercial offering of the new entity.

Charter developed an extensive plan to generate operational synergies and rationalize the new entity’s offering.

Industrial Equipment: Konecranes + MHPS

Konecranes is a global provider of industrial and port cranes equipment and services. Several years ago, in the face of increased competition, Konecranes was struggling to cut costs or grow organically. In 2016, it bought a business unit from Terex Corporation called Material Handling & Port Solutions (MHPS), its principal competitor. The MHPS business included several brands that complemented Konecranes’ products and services, along with some sizeable overlaps in technology and manufacturing networks.

Before the deal closed, Konecranes drafted an ambitious full-potential plan to generate about $160 million in synergies within three years through cost reductions and new business. That represented a 70% improvement over the joint company’s pro forma financials. The turnaround plan encompassed all main businesses and functions across both legacy Konecranes and MHPS operations.

As part of the preclose planning, Konecranes’ leaders designed an overall transformation to start after the merger was finalized. The program covered all business units and functions and was extremely comprehensive, including the following:

- Reducing procurement spending through increased volumes

- Consolidating service locations

- Aligning technological standards and platforms

- Closing some manufacturing sites

- Streamlining corporate functions

- Adopting more efficient processes

- Optimizing the go-to-market approach

- Identifying new avenues of growth

The full program consisted of 350 individual initiatives, organized into nine major work streams and aligned with the overall organization structure to create clear accountabilities and tie the program’s impact directly to financial results. Still, many of the initiatives were complex by nature, so solid planning and rigorous program management and reporting have been critical.

Konecranes also carried out a holistic baseline survey to assess the cultures of the two organizations and define a joint target culture. An extensive cultural development and communications plan featured strongly in the early days of the integration.

The company has reported on its progress to investors as part of its quarterly earnings calls, and two years into the three-year plan, it has hit or exceeded its targets. That performance has earned praise from investors, leading to a share price increase of more than 50% since the acquisition was announced.

Key success factors in this turnaround: The combination of competitors presented a clear opportunity to create value from synergies, but management took the more ambitious approach of using the deal as a catalyst for the combined entity to perform at its full potential. Hitting—and often exceeding—performance targets has led to a dramatic rise in the company’s stock price.

Konecranes used the deal as a catalyst for the combined entity to perform at its full potential.

Retail Grocery: Coop Norge + ICA Norway

Coop Norge ranked third in Norway’s competitive and consolidated retail-grocery landscape in 2014, with a 22.7% share. But the company faced a major strategic challenge from its two larger competitors, which were able to use their scale advantages to negotiate favorable prices from suppliers while opening new stores. A smaller player, ICA Norway, was in a more precarious position, with a 2014 operating loss of more than $57 million on revenue of $2.1 billion. An acquisition made sense. In buying ICA, Coop aimed to become the number-two player and so increase economies of scale in procurement and logistics. ICA stores in Norway were a strong strategic fit as well, complementing Coop’s existing locations.

After the acquisition closed, Coop rebranded all ICA supermarkets and discount stores to concentrate on fewer, winning formats and to fully leverage improvements and synergies in areas such as procurement, logistics, and store operations. Coop’s discount brand, Extra, was already showing good momentum in the market, and this was accelerated through the ICA Norway transaction.

The integration and rebranding created pride and momentum internally at ICA, which led to improved growth and financial performance at the acquiring company as well. Coop moved up to second place in the market, generated new economies of scale, and realized 87% of its expected results from synergies within just eight months of the close and 96% after two years. And because the company stayed true to its existing store strategy, it was able to lean on previous experience and maintain its long-term vision. Operating profits rose by approximately $270 million, from a loss of $160 million in 2015 to a profit of $106 million in 2016. Revenue during that period increased by 10.7%, to nearly $6 billion, of which ICA stores and Coop’s existing locations accounted for 7.8 and 2.9 percentage points, respectively.

Coop Norge’s early successes in the integration created strong momentum and a culture of success.

Key success factors in this turnaround: The early successes achieved in the integration created strong momentum and a culture of success, enabling the combined entity to increase both revenue and profits in a highly competitive market.

Shipbuilding: Meyer Werft + Turku Shipyard

In the early 2010s, the global shipbuilding industry declined significantly, in part because of a contraction in the demand for ships. That left many shipyards—including the Turku yard, which operated in the sophisticated niche of cruise ships and ferries—in need of cash. When Turku’s owner, STX Finland, verged on insolvency in 2014, the Finnish government (which had a stake in STX) began looking for a new owner. Meyer Werft, a leading European shipbuilder, believed that the Turku shipyard could be operated profitably and bought 70% of the yard in September 2014. As part of the deal, Turku secured two new cruise ship projects. With the orders confirmed, Meyer Werft bought the remaining shares, becoming sole owner.

Renamed Meyer Turku Oy, the company began to integrate the shipyard’s operations and find synergies in development, procurement, and other support functions. Having negotiated up-front for new business, it was able to fill Turku’s production capacity, benefit from increased scale, and begin to boost profitability almost immediately. Critically, the deal helped restore trust among employees, which extended to other important stakeholders such as customers and lenders. Such trust is essential in an industry that hinges on building a small number of very large projects, and it was fostered by Meyer Werft’s delivery on promises right from the start.

Meyer Werft then looked to planning growth in the longer term: increasing capex to boost capacity—and profitability—still further and investing in a new crane, cabin production, and a new steel storage and pretreatment plant while modernizing existing equipment. It also entered into a joint R&D project with the University of Turku to develop more sustainable practices across a ship’s life cycle—from raw materials to manufacturing processes and beyond. And it hired 500 new workers, partially replacing retiring employees, in 2018.

As a result, the company increased revenues from $590 million in 2014 to $970 million in 2017, an annual growth rate of more than 18%. It also increased profit margins to 4% in 2017, up from a loss of 5% in the acquisition year. The company now has a stable order book out to 2024, and productivity continues to climb.

Key success factors in this turnaround: In addition to making operational improvements, Meyer Werft was able to foster trust among employees and customers by delivering on its promises and showing its commitment through long-term investment.

Meyer Werft fostered trust among employees and customers by delivering on its promises.

Retail: Office Depot + OfficeMax

In early 2013, Office Depot and OfficeMax were in a similar situation: online retailers were threatening their business. They agreed on a merger, with the goal of generating synergies by reducing the cost of goods sold, consolidating support functions to cut overhead, and eliminating redundancies in the distribution and sales units.

Because the two companies were merging as equals—rather than one buying the other— some decisions were difficult to make before the close (for example, which IT system the combined entity would use and where headquarters would be located). But management was able to define synergy targets and begin planning the integration during the six months before the close. The companies also created an integration management office (IMO) that addressed areas that were critical for business continuity, specifying which units would be integrated and which would be left as is.

The IMO created playbooks for 15 integration teams, addressing finance, marketing, the supply chain, and e-commerce operations, and developed a plan for communication, talent management, and change management for the overall effort. It categorized all major decisions into two groups: those that could be made prior to the close (because the steering committee was aligned) and those that couldn’t be made during that period. For decisions in the second category, the IMO laid out the two or three best options to consider. Critically, the IMO’s rigorous plans included timelines for how the businesses would evolve over the first, second, and third years of the merger, helping to align functions and manage interdependencies.

Once the deal closed, all this preparation allowed the two organizations to start the integration process immediately on day one. Within weeks, they had agreed on a leadership team for the combined entity, a headquarters site, and an IT platform. The organization was largely redesigned in just two months—a remarkably rapid effort given that it ultimately affected about 9,000 employees.

Most important, the smooth integration process allowed the companies to be extremely rigorous in capturing more synergies—and doing it faster—than anticipated. For example, they integrated the e-commerce businesses in a way that allowed them to retain most key customers. In the first year after the deal closed, the company captured cost savings close to three times management’s original targets; cost savings of the end-state organization were 50% more. In all, the merger unlocked about $700 million, putting the new company in a much better competitive position.

An extremely rigorous integration plan allowed Office Depot and OfficeMax to exceed cost savings targets.

Key success factors in this turnaround: Office Depot and OfficeMax merged in response to the threat of online competition. An extremely rigorous integration plan allowed the combined business to dramatically exceed its cost savings targets.

Energy: Vistra + Dynegy

Texas-based Vistra Energy operates in 12 US states and delivers energy to nearly 3 million customers, with a mix of natural gas, coal, nuclear, and solar facilities enabling about 41,000 megawatts of generation capacity. It was formed in October 2016 when its predecessor emerged from a protracted bankruptcy process.

At the conclusion of bankruptcy proceedings, Vistra underwent a corporate restructuring, moving from a siloed operating model to a unified organization with a centralized leadership team and common objectives. New governance structures facilitated more consistent and rigorous corporate decision making, with an emphasis on capital allocation and risk management. In addition, management immediately launched a turnaround effort to reduce costs and improve performance across the entire organization.

In all, the company managed to reduce costs and enhance EBITDA by approximately $400 million per year, exceeding its original target by $40 million without any drop in service levels or safety standards. At the same time, investments in new service offerings—many enabled by digital technology—boosted customer satisfaction.

In 2017, Vistra announced the acquisition of Dynegy, one of its largest peers, resulting in the largest competitive integrated power company in the US. The combined entity offers significant synergies, with Vistra now on track to deliver $500 million of additional EBITDA per year, along with annual after-tax free cash flow benefits of nearly $300 million and $1.7 billion in tax savings. The deal also allows Vistra to expand into new US markets, diversifying its operations and earnings, reducing its overall business risk, and creating a platform for future growth.

The addition of Dynegy also supports Vistra’s shift toward a more modern power generation fleet based on natural gas. The company preceded that deal with the acquisition of a large, gas-fueled power plant in west Texas, and it also retired several uneconomical coal-burning facilities. In all, Vistra’s generation profile has evolved from approximately two-thirds coal-fueled sources to more than 50% natural gas and renewables.

With these measures—a successful turnaround followed by two strategic acquisitions—Vistra has positioned itself to sustainably create value for its shareholders in a very competitive industry.

Key success factors in this turnaround: Vistra’s acquisition of Dynegy represented both a pivot to growth and an opportunity to extend cost savings to an acquired operating platform.