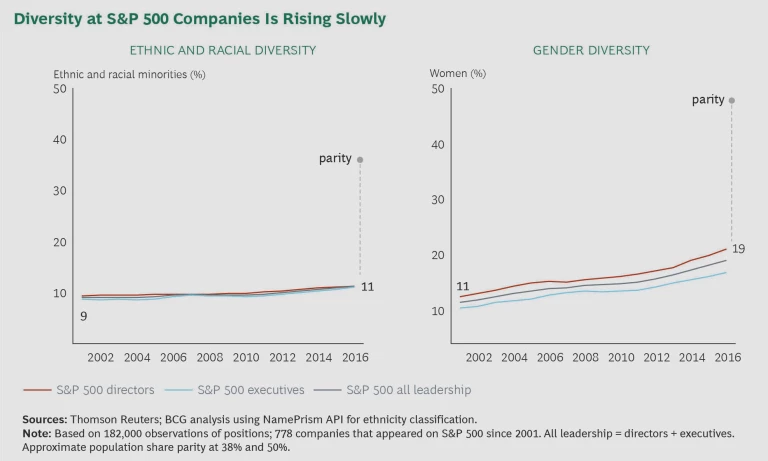

How often have you heard a CEO say, “I am happy with the diversity of our organization?” We have yet to meet such a CEO. Diversity in large organizations continues to be elusive, in spite of prolonged efforts and investments and the proliferation of diversity initiatives across companies. Only about 11% of senior leaders in S&P 500 companies hail from ethnic and racial minorities, up only 2% from 15 years ago and still quite far from 38%, the share of US adults representing ethnic and racial

2. In 2015, 61.6% of Americans reported their race in the US Census as “white alone, not Hispanic or Latino.”

These broad patterns also hold globally. According to World Economic Forum estimates, the global gender gap will take an astonishing 170 years to close unless progress

There is strong evidence that diversity can improve the performance of organizations, particularly those relying on creativity and

Our perspective is grounded in our experience managing a global professional services firm, whose success depends on attracting and retaining diverse talent and leveraging it to create unique solutions to clients’ complex problems. We also draw on our research with Simon Levin of Princeton University on the resilience and adaptability of biological and social

We Need a New Approach

We can define diversity as the variety of relevant human characteristics in an organization. Traditionally, diversity initiatives have focused on a handful of characteristics associated with a history of discrimination: gender, race, religion, and sexual orientation. The first wave of diversity initiatives set out to achieve workforce composition targets and to stamp out discrimination, sexual harassment, racism, the more subtle problem of “unconscious bias,” and other manifestations of a hostile work environment. Such initiatives were an entirely necessary step that likely also improved organizational performance by ensuring that talented people were retained and didn’t have to spend time and energy fighting for basic rights. While we’ve made some progress, it’s clear that the battle is far from won with respect to either rebalancing organizational composition or eliminating workplace hostility.

But compositional diversity doesn’t automatically translate into better performance. Drawing on our work on biological systems, we posit that organizations need a new approach to fully harness the power of diversity. This entails not only increasing diversity but also building appropriate mechanisms to select the best ideas and practices that emerge from a diverse workforce, thus unleashing the power of diversity.

Compositional diversity doesn’t automatically translate into better performance.

Diversity Is More Necessary Than Ever

The need to put diversity to work is more urgent than ever. Rapid changes in technology, globalization, and politics continue to upend the business environment and curtail the longevity of companies. As we have shown, public companies now have a one-in-three chance of perishing over a five-year horizon, whether through failure, takeovers, or other causes. That’s six times higher than the mortality rate for companies

In light of this uncertainty, leaders need to shift their attention from incrementally optimizing efficiency in known, stable environments to preparing their organizations to survive and thrive when confronted with unknown and unknowable factors. This ability to thrive in the face of uncertainty and change—resilience and adaptability—depends to a large extent on diversity.

The ability to thrive in the face of uncertainty and change depends to a large extent on diversity.

The Value of Diversity in Complex Systems

Diversity is crucial for the functioning and survival of any organism or complex adaptive system, including an organization. In such systems, local events and interactions among the “agents,” whether ants, trees, or people, can cascade through and reshape the entire system—a phenomenon called emergence. The system’s new structure then influences the individual agents, resulting in further changes to the overall system. Thus the system continually evolves in hard-to-predict ways through a cycle of local interactions, emergence, and feedback.

Our research at the intersection of business strategy, biology, and complex systems shows that long-lived systems display six characteristics, one of which is diversity. Diversity is crucial for organizations for two reasons.

First, diversity builds resilience. An effective way to bring down a system is to narrow how it responds to change. Enduring systems comprise a broad variety of agents, which behave and respond to external stimuli in varying ways. As a result, an attack on the system is less likely to break it. This is a foundation for resilience.

Second, diversity is the basis of adaptiveness. Diversity of problem-solving heuristics and behavior permits a system to evolve and learn from experience. Imagine an institution that cannot do those things. Over time, it will be increasingly maladapted to its changing environment, and its survival will be threatened. Internal variety—diversity—provides the grist for the system to test ideas and actions and select the most effective in each environment.

Diversity of problem-solving heuristics and behavior permits a system to evolve and learn from experience.

Human organizations are particularly rich in this respect, because people can not only learn from experience but also infer and extrapolate from their experience to other situations by conducting thought

Diversity Also Requires Selection and Amplification

These insights from complex adaptive systems illustrate why aiming for compositional diversity is only a first step. In the language of evolutionary biology, the full benefits of diversity are achieved only if, in addition to variation stemming from diversity, there are effective selection and amplification mechanisms, so that the best approaches are identified and propagated throughout the organization. An example of an organization that has accomplished this is Alibaba, the Chinese e-commerce giant. Alibaba has many different autonomous business units (diversity) that experiment with new ideas. Those that perform best in the market are recognized (selection) and given more resources

In human organizations, establishing effective selection and amplification mechanisms is hard. It requires the careful tuning of processes, metrics, incentives, culture, and other factors. We can view such measures as falling under the umbrella of inclusion. In modern organizations, inclusion programs can involve, for example, training people to embrace various styles of communication and incorporating multiple perspectives in decision-making processes. However, it is not the functional focus of a program that makes it effective, but the creation of an adaptive mechanism with the three components of variation, selection, and amplification.

A New Mindset for Leaders

Drawing on our research in biology and strategy, we propose six principles for a new paradigm to unlock the potential of diversity. These are simple ideas, but nonetheless few organizations are yet embracing and implementing them.

1. Don’t rely only on a top-down mandate. Because organizations can’t expect the same prescriptions to work in different situations, top-down and company-wide diversity mandates alone won’t work. Leaders must learn to manage more indirectly: to inform people what the goal is and give them the tools and the encouragement to experiment. Organizations with an adaptive, flat, flexible, risk-tolerant structure will likely have more success in achieving performance-enhancing diversity in today’s dynamic business environments.

This bottom-up emphasis empowers frontline leaders, who can take it upon themselves to experiment and figure out what works in their specific contexts.

2. Acknowledge that the path can be complex and unpredictable. In complex adaptive systems, everything interacts. It can be hard to disentangle what works and what does not. The system cannot always conveniently be decomposed into separately manageable components. Therefore, organizations cannot be too simplistic in their prescriptions for improving performance through diversity. The optimal level and quality of diversity depend on the context and the problem to be solved. The ideal mix and set of measures may be unknowable in advance and may evolve as the context changes.

Organizations must therefore be patient and try a variety of interventions, alone and in combination, across locations, functions, and time. There may be few silver bullets or sure bets; there will likely be a lot of failure along the way, and single-variable correlations may not be instructive in determining which interventions to pursue across the board. We should expect that what worked there will not necessarily work here, and what worked then will not necessarily work now. This accounts for the contradictory beliefs and evidence concerning what works and what doesn’t. It also explains why we often find ourselves needing to qualify our preferred programs with the caveat “if done right.”

3. Move beyond simple compositional diversity. Many diversity programs include compositional targets, such as matching the workforce to the surrounding population on a few demographic dimensions. This approach is entirely defensible as a way to eliminate biases, which are both unfair and unproductive. But it will not necessarily result in the specific mix of resources required to address particular challenges.

Organizations need to consider people holistically rather than along a few prescribed dimensions—such as educational background and working style—thus allowing for human multidimensionality. Eventually, diversity programs will need to focus on individuality and customization for all employees, rather than only a few groups. There’s already a trend in this direction—take a look at the proliferation of diversity categories (age, sexual orientation, extraversion/introversion, and so on). Such multidimensional approaches will be most impactful when they also increase the effectiveness of companies’ vary-select-amplify learning processes. Programs should thus aim to maximize the variety of perspectives and improve the selection and amplification of the best ideas that emerge from this.

4. Embrace the paradox of being simultaneously inclusive and hard-nosed. Inherent in our view of diversity is a paradox: equality of opportunity is necessary for diversity, but it takes hard-nosed judgment to choose the best ideas that come out of a diverse group to solve a particular challenge. To support a culture of diversity, people are often coached to be collaborative and noncritical rather than discerning. The hard truth is that they need to be both. We have shown that ambidextrous organizations—those that can explore new opportunities and exploit existing ones—are more successful in the long term. They combine both qualities.

How can organizations resolve this tension? They must be inclusive enough to attain a sufficiently diverse composition, but they must also establish processes and procedures to select the best ideas. This requires a delicate balance: people must trust one another enough to work together, but they must not allow groupthink to undermine adaptation and learning.

5. Foster dissent and discord. An organization constantly taking advantage of the “grist for the mill” that diversity provides will necessarily have a lot of perspectives and opinions. Leaders need to ensure that the work environment makes it safe for employees to raise objections, actively debate alternatives, and be contrarian, even to superiors.

This attitude also needs to extend to the organization’s approach to diversity. Diversity programs have a tendency to develop a narrow range of accepted language, philosophy, and action, and any deviation can be frowned upon. This kind of prescriptive, rigid approach is entirely contrary to the adaptiveness and flexibility that are required. In short, there must be diversity of cognition and approach in the diversity department, too!

6. Embed the diversity program within a larger ecosystem. Many diversity programs are focused entirely within the boundaries of the firm. But firms are embedded in larger ecosystems of supply chains, industries, and societies. If a company’s broader ecosystem is not considered, a number of opportunities are left on the table: First, the opportunity to deploy diversity to solve diverse customer problems more effectively. Second, the ability to deploy diverse resources to better relate to a wider range of customers. Third, the ability to learn from customers’ approaches to diversity and then use these learnings to drive internal change. And fourth, the opportunity to help customers with their own diversity challenges.

How Do We Know When We Are Done?

In complex adaptive systems, including corporations, diversity is essential to survival and performance. But a diverse composition of agents is not enough; that diversity needs to be put to work though adaptive mechanisms that continually select and amplify diverse behaviors at a local level. Diversity and adaptation therefore need to be baked into every aspect of a company to be effective, not merely appended to the organization in the form of a top-down initiative. In this sense, we will know we have arrived at our destination when diversity and adaptive thinking have become what they should be: matters of business common sense.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.