“Yesterday, love was such an easy game to play.”

—Paul McCartney, 1965

Many business leaders have spent their careers in times of relative economic predictability and political stability, punctuated by occasional market downturns. As a consequence, they have been able to focus on activities that are directly related to the “business of business,” such as competitive strategy, innovation, operations, and human resources.

In hindsight, yesterday’s business game was a relatively easy one to play.

Leaders today increasingly find themselves in unfamiliar territory marked by high levels of uncertainty and instability, a global economy that is growing more slowly, and new political realities. These change the relationship between business and other parts of society; they also have profound implications for strategy and competitive advantage.

Political and Economic Uncertainty Matters

Today’s multidimensional uncertainty is in part a byproduct of two important drivers of economic growth in the past 40 years: global economic integration and technological innovation. Together, they have increased global prosperity but have also contributed to inequality within countries, giving rise to protectionist policies that directly affect trade, taxation, and

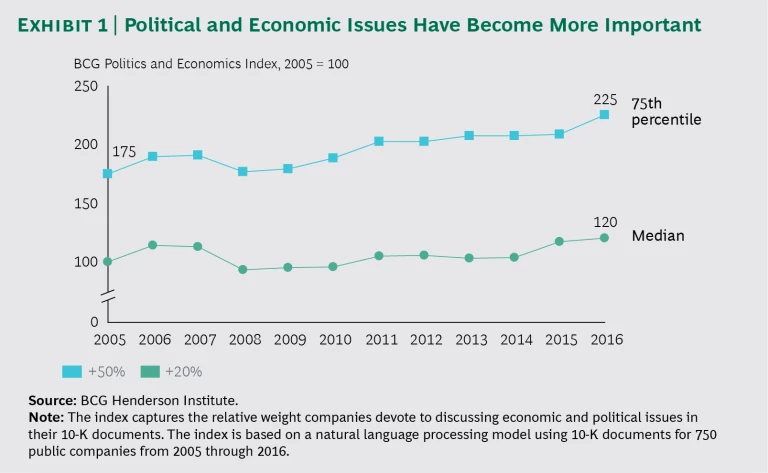

In this tightly intertwined world, companies feel the impact of political and economic factors more acutely. A recent BCG Henderson Institute analysis applying natural language processing (NLP) to S&P 500 companies’ investor communications shows that many executives now devote more attention to reacting to and shaping political and economic issues. (See Exhibit 1.)

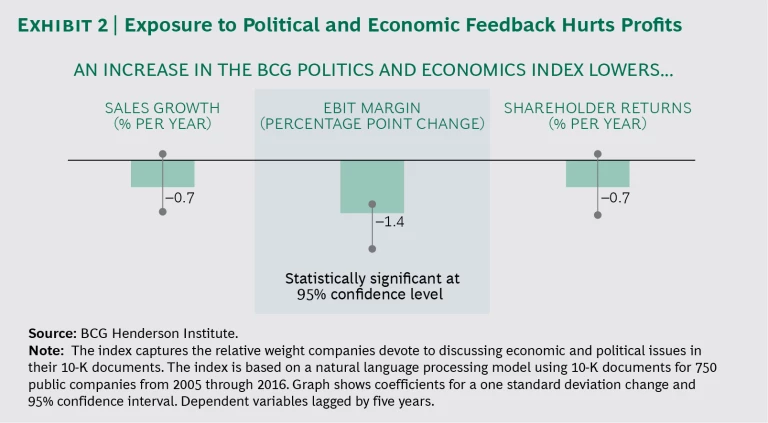

Does it matter? Our research shows that firms that are more exposed to political and economic feedback tend to have lower profit margins. (See Exhibit 2.)

This is not a surprise. Political and regulatory intervention and economic volatility do not generally help profits. But interestingly, the effects on growth and value creation are more ambiguous. Even in situations of high political and economic exposure, savvy leaders can mitigate negative effects and create competitive advantage.

The increasing interconnectedness of business, economic, and political spheres causes disturbances to spread more quickly. From the perspective of corporate leaders, that translates into increased change and systemic uncertainty, with tangible business consequences. The performance gap between winners and losers in all industries is already bigger than ever, and large companies in particular are struggling to find growth. As a result, companies are now dying sooner—the five-year mortality rate has risen from 5% in 1970 to around 32%

A New Mental Model: From Chess to Matryoshka Dolls

To thrive in this new climate, leaders need a different mental model for business strategy. Instead of seeing it as a self-contained game of chess, leaders should perhaps visualize it as a Russian matryoshka doll, the endearing set of wooden figures that are stacked inside one another. Why? Business today is part of a nested set of so-called complex adaptive systems: interconnected, dynamic systems in which local perturbations can give rise to unpredictable global effects and vice versa. As a consequence, leaders need to be able to both grasp each level and master the art of playing on more than one level at a time.

What does such a nested set of systems look like in business? Companies are part of business ecosystems, which in turn are embedded in local and national economies, which are interwoven with societies. Changes at lower levels (within industries and between firms) influence higher levels, such as the economy and the political system, which in turn reshape the fates of the systems within them—namely, companies.

In more predictable times, there is a stable equilibrium between levels, permitting business to focus mainly on business considerations. Today, the opposite is true. Many business leaders tell us that political and economic considerations currently impact performance expectations more than purely competitive considerations do. It is impossible to run a business nowadays without at least considering what is happening on other levels.

Business today is part of a nested set of so-called complex adaptive systems.

Nested Complex Adaptive Systems in Practice

Take the US retail industry, for example. Encouraged by China’s entry into the WTO in 2001, US retailers built tightly orchestrated supply chains across the globe, taking advantage of a new politically induced opportunity for global cost arbitrage. These sourcing and logistics decisions have had significant effects on economic, social, and political levels. A first direct result was the lowering of domestic prices for many household goods—in fact, this effect was so strong that the US Federal Reserve took it into account when deciding on interest rates. A more indirect result of these business decisions was the displacement of production activity in the US, leading to job losses, a new sense of social and economic insecurity, and ultimately a nativist political backlash against the trade policies that started this particular wheel spinning.

These effects were complicated by technological advances, which increased factory productivity and further reduced manufacturing employment even as domestic manufacturing output increased. In recent years, US retailers have been trying to increase the weight of domestic sourcing. This comes late, possibly too late to preserve the current model of global economic arbitrage. A border tax, still under consideration in some US policy circles, could even undermine this game entirely by wiping out a majority of the industry’s

Imperatives for Business Leaders

What should business leaders do now? Above all, they need to understand that focusing only on the narrow game of business has become a risky proposition. They need new approaches for understanding, managing, and shaping the phenomena that arise from nested dynamic systems. Going forward, leaders should embrace five imperatives to expand their game and ensure that their companies thrive under more complex conditions.

- Build multilevel scenario analysis skills. In this new environment, firms need to become more politically and economically astute. For that, they first need to develop political and economic analysis capabilities in order to understand what is happening in each layer and to model implications and strategic choices. This analysis should rely not only on textbook theory and point predictions but also on empirical evidence from analogous situations. Consider exchange rate risk. While textbook economics suggests that the depreciation of the British pound would increase prices (and lower demand) for imports, past experience with exchange rate adjustments shows that the effect on a particular company relative to competitors depends on many firm-specific factors. Leaders should then probe the effects of political and social shifts on their strategies. Contingent thinking helps. This involves developing scenarios that are rich and broad enough to challenge the implicit assumptions behind strategies, investment plans, and initiatives. Ideally, scenario analysis is not a one-off (or annual) exercise but part of an ongoing examination of strategy. Leaders can use these scenarios to define signposts (“If we see events of type x, this validates belief y”), build better antennae to pick up signals earlier (“If we see x, type x events are likely to occur soon”), and discuss conditional actions (“If we see x, then do y”). This is easier said than done. Take European utility companies, for example, which—despite substantial political capacities and sophisticated scenario analysis skills—still struggled to grasp the impact of green energy preferences and policies on their business models.

- Become more resilient. Given the inherent unpredictability of nested complex systems, not every adverse effect on business can be foreseen or mitigated. This means businesses need to become more resilient so that they can sustain and possibly even gain relative advantage from external shocks. Biological systems have evolved this quality over time. In our research, we found that organizations are more robust if they have three qualities of such systems: redundant elements (in their manufacturing network, for instance), internal diversity (such as in problem-solving approaches), and modularity (a network of loosely linked instead of tightly integrated parts). For example, when a fire destroyed the production lines of one of Toyota’s key suppliers, the company was able to quickly activate and switch to other suppliers, avoiding assembly line interruptions that could have cost Toyota millions of dollars.

- Shape the system. To moderate their exposure to uncertainty, large firms can strategically shape their immediate neighborhood to build safe havens of relative predictability. They can do so by controlling the context in which value is created or exchanged. Ecosystem formation (of suppliers and partners, for instance) is one such strategy, because it can allow the orchestrator to shape the context by establishing control over information flows and pricing mechanisms. Consider Amazon. By partnering with thousands of smaller independent e-commerce players, Amazon sees external shocks sooner, can percolate change within its own operations faster, and can adjust the degree of coupling between itself and players by changing the terms of exchange. It can also buffer itself against change by being agnostic to the product portfolio transacted on its platforms.

- Recreate the narrative. In the long run, few things are as powerful as ideas. To get a better feel for the emergence of ideas that can spread and shape social and political layers, firms need to engage diverse audiences beyond their target customers and listen more closely to them. From that starting point, they should also aim to shape the discussion. Narratives, essentially storified ideas, are powerful because they can redefine what is legitimate and valuable. Take GE, for example. In a well-received and widely cited speech in 2016, CEO Jeff Immelt laid out a new vision for the future of globalization and reiterated GE’s commitment to building manufacturing centers and capabilities across the globe. In other words, GE is attempting to rewrite the narrative of globalization to address widening faults in the prevailing one.

- Reframe leadership. Leaders need to continue focusing on value creation for customers and shareholders, but they must do so within new constraints created by economic and political layers in the broader system. To do so, leaders need to broaden their leadership repertoire. In particular, they need to increase their contribution as antennae that sense changing political and social signals and as disruptors that translate external change signals into organizational action and overcome organizational inertia. To shape the system and the narrative, leaders must balance the need for higher visibility into and influence on economic and political layers with a sense of humility about their own degree of control over desired outcomes.

Individuals, companies, economies, societies, and political systems are increasingly and inextricably connected, making it harder than ever to understand and steer individual firms in terms of business considerations alone. In times like these, the business of business requires more than just executing or thinking about business. To refresh their game, leaders should see their firms as embedded in interconnected, nested local and global systems. Leaders who understand and are able to maneuver in this new environment will position their companies to take advantage of these new complexities.

The BCG Henderson Institute is Boston Consulting Group’s strategy think tank, dedicated to exploring and developing valuable new insights from business, technology, and science by embracing the powerful technology of ideas. The Institute engages leaders in provocative discussion and experimentation to expand the boundaries of business theory and practice and to translate innovative ideas from within and beyond business. For more ideas and inspiration from the Institute, please visit Featured Insights.