Most organizations report that their workforce includes relatively few employees with disabilities: just 4% to 7% on

We are not the only ones finding a higher prevalence of disabilities among the workforce. Our survey’s self-identification rate falls within the range of prevalence rates for workers with disabilities or health conditions across several countries: approximately 13% to 30%.

The disparity between the prevalence rates that employers report and the self-identification rates that employees shared with us reveals three troubling workplace realities:

- Employees with disabilities significantly underdisclose to their employers, perhaps fearing stigma or a negative impact on their job security or promotion prospects.

- Employers are missing a large-scale opportunity to enable a quarter of their workforce to bring their full selves to work.

- And employers making decisions and investments regarding their workforce are relying on inaccurate information. If management doesn’t understand the true number of people with disabilities (PwD), it’s hard to make a case for developing tailored support systems that could have significant benefits.

BCG’s BLISS Index, which measures employees’ feelings of inclusion, provides a quantitative window to understand the workplace experience of employees with disabilities today. BLISS stands for Bias-Free, Leadership, Inclusion, Safety, and Support, and the index provides a single, comprehensive score that reflects feelings of inclusion. Scores range from 1 to 100 and are based on rigorous statistical modeling.

Inclusion—which we define as feeling valued and respected; believing your perspectives matter; feeling happy, motivated, and like you belong; and feeling that your mental and physical well-being is supported—matters. Done right, inclusion positively changes the workplace experience, and not just for marginalized groups: inclusive cultures benefit all employees.

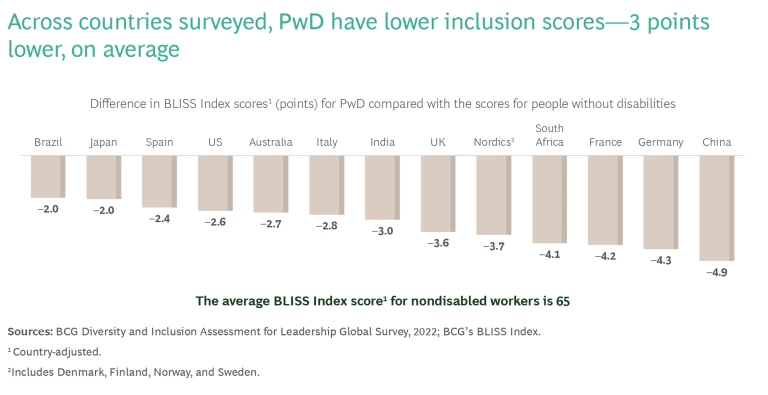

But for people with disabilities, we found a disappointing state of affairs. Unsurprisingly, PwD report lower levels of inclusion in the workplace relative to their colleagues without disabilities: the average BLISS Index score for PwD is 3 points lower than the average score for those without a disability or health condition. These findings hold true across the countries included in our research.

But the scores for PwD are also 1 to 2 points lower than those for other employee groups that are often the focus of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts: women, the LGBTQ community, and Black, indigenous, and other people of color.

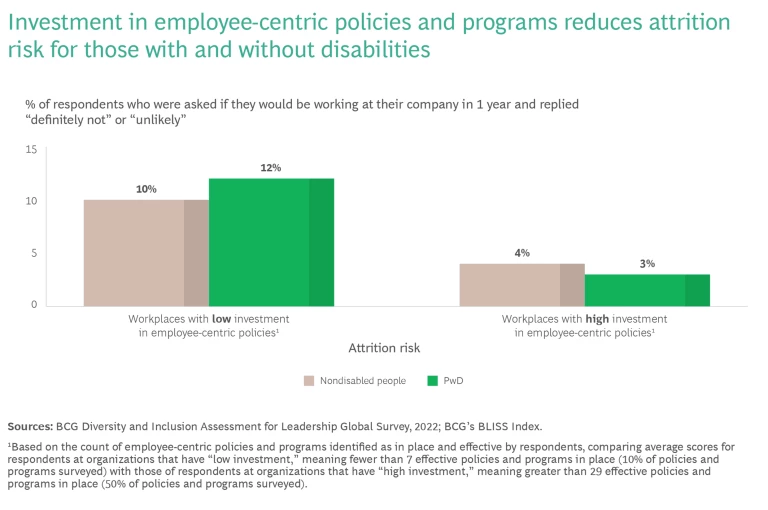

These findings matter because lower feelings of inclusion are correlated with higher attrition.

But, as we demonstrated statistically via BLISS, improving an employee’s feelings of inclusion increases the likelihood that they will stay with the organization. For example, a 5-point increase on the BLISS Index corresponds to an approximately 2.5% reduction in attrition risk. For an organization with 1,000 employees, that translates to 25 employees staying rather than leaving—and taking their expertise and institutional knowledge with them. In today’s environment of low unemployment and costly hiring and training, the economic impact on organizations can be substantial.

Beyond differences in BLISS Index scores, our survey also found that PwD are having a more negative work experience: PwD are 6 percentage points less likely than nondisabled employees to indicate they are happy at work. They are nearly 15 percentage points more likely to say that work negatively impacts their mental and physical well-being and their relationships with friends and family. And they are 1.5 times more likely to have experienced discrimination at their organization than those without a disability or health condition.

Given the disconnect between perceived prevalence and self-disclosure rates and given the worse experiences of PwD in the workplace, it’s clear that organizations need to create a more inclusive culture. Good news—our data shows that organizations can foster greater feelings of inclusion for PwD by providing:

- Employee-centric policies and programs

- Mentorship

- Reasonable accommodations

There’s another way to increase feelings of inclusion: at organizations that have put the above recommendations in place—thereby fostering a more inclusive environment—employees with disabilities can feel safe and supported in disclosing their disability, creating more opportunities to ask for what they need and to perform at their best. And doing so creates more-accurate people data, which allows employers to assess and invest appropriately and thereby maximize workplace productivity.

Our Report Methodology

This research draws upon a survey of approximately 28,000 employees conducted by BCG over the summer and fall of 2022 in 16 countries: Australia, Brazil, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Norway, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, UK, and US. Survey respondents were part-time and full-time employees of companies with 1,000 or more employees. The participating companies spanned many industries.

The survey captured self-reported data. Approximately 7,300 respondents (approximately 25% of our full data set) identified themselves as having a current or periodically occurring health condition, disability, or challenge that limits a major life activity. (See “Disability, Defined.”)

In addition to the survey, we conducted interviews:

- With currently employed individuals who identified as having a disability

- With disability inclusion and accessibility experts: Judy Heumann, Andraéa LaVant of LaVant Consulting, Ben Gauntlett of the Australian Human Rights Commission, Daniel Cadey of Business Disability Forum, Jenny Lay-Flurrie of Microsoft, Jill Houghton and Russell Shaffer of Disability:IN, and Nipun Malhotra of Nipman Foundation (Nipun is also a contract employee of BCG).

Much of the quantitative research in this report utilizes BCG’s BLISS Index, a comprehensive, statistically rigorous tool that identifies the factors that influence feelings of inclusion in the workplace—and meaningfully correlate with retention. (See “BCG’s BLISS Index and Its Role in Our Findings.”)

Disability, Defined

Respondents could identify as having one or more types of disabilities or health conditions that limit major life activities, including deafness or severe hearing impairment, blindness or severe visual impairment, a condition that limits physical activity, a mental health condition, a chronic condition, a neurological divergence, a visible difference (for example, scars or being born with fewer or shortened limbs), or other disabilities or impairments that limit major life activities.

Other entities define disability in similar ways. For example:

- United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD): “Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): “A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions).”

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: “Disability is an umbrella term for any or all of the following components, all of which may also be influenced by environmental and personal factors: impairment—problems in body function or structure; activity limitation—difficulties in executing activities; or participation restriction—problems an individual may experience in involvement in life situations.”

But the manner in which surveys ask people to self-identify as having a disability varies, leading to a range of prevalence rates, as demonstrated by these examples: Our research estimates that 13% to 30% of workers have a disability. The Center for Talent Innovation found that 30% of white-collar workers in the US say they have a disability or health condition, and data from the CDC and the Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that roughly 17% of workers have a disability or health condition. Additionally, about 13% of Australian workers have a disability, according to the Australia Institute of Health and Welfare.

For simplicity, our report uses the term people with disabilities (PwD). However, people with disabilities have different terminology preferences when referring to their disability. Some people see their health condition or disability as inherent to their identity and prefer identity-first language, such as deaf person or autistic person. Others prefer person-first language, such as person who is deaf or person with autism. And in terms of affiliation, some people prefer to identify themselves as part of the disability community and others do not see themselves as having a disability and prefer to identify only with their specific condition, such as having a chronic illness or mental health condition or being neurodiverse.

BCG’s BLISS Index and Its Role in Our Findings

To create the BLISS Index, BCG drew upon self-reported data from approximately 28,000 employees in large companies (those with 1,000 or more employees) across 16 countries. We applied statistical modeling to understand what drives feeling of inclusion and identify patterns in the correlations between responses.

The result is a single, comprehensive score ranging from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater inclusion, a global average score of 65, and normal distribution patterns.

A one-point difference in the BLISS Index score changes attrition risk, leading to a materially important difference in the number of employees at risk of leaving a company.

Three Moves That Organizations Can Make

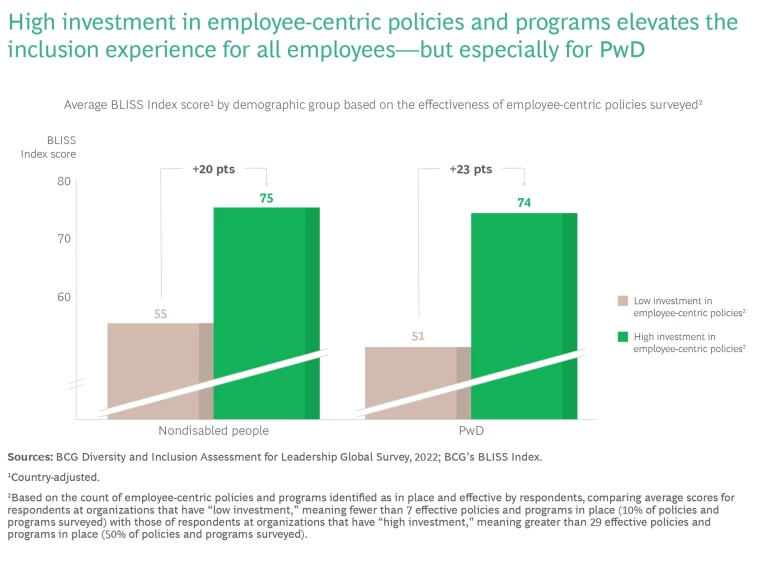

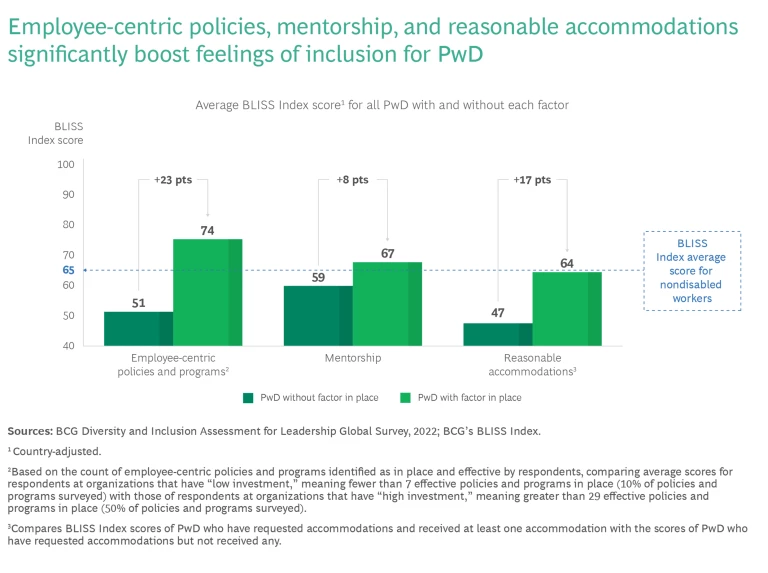

Our global research showed that organizations can significantly improve feelings of inclusion for PwD through targeted actions: investing in employee-centric policies and programs, providing mentorship programs, and offering reasonable accommodations. The first two moves improve feelings of inclusion for all employees—but disproportionately so for PwD, lifting this group’s BLISS Index score to a level similar to that experienced by nondisabled employees. The third move is specific to employees with disabilities.

Investing in Employee-Centric Policies and Programs

As part of our survey, we asked respondents about some 60 policies and programs intended to improve the employee experience, such as appointing a chief diversity officer, tracking and publicly sharing DEI metrics, and offering flexible working arrangements. We used the percentage of policies and programs that respondents reported as available and effective in their organization to identify two broad work environments:

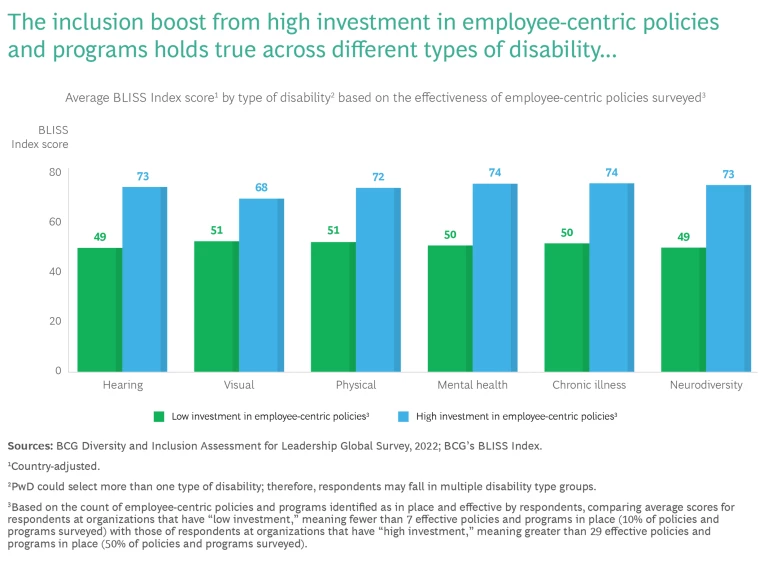

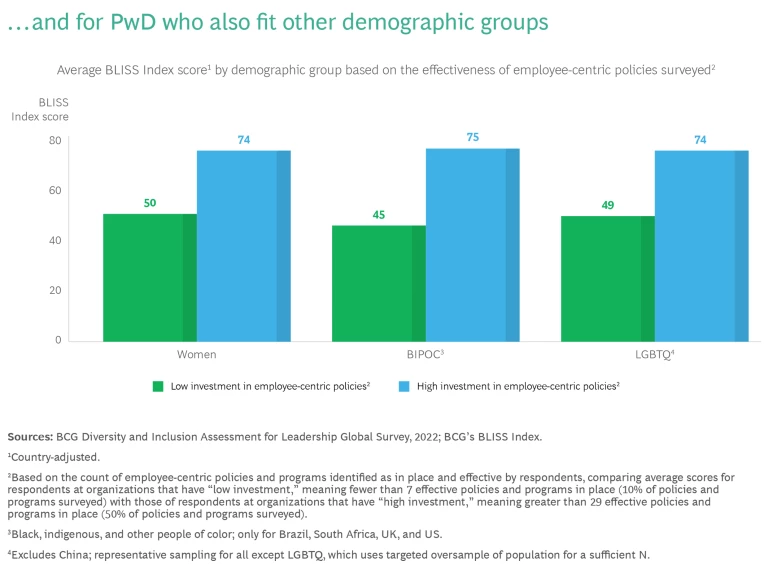

- Work Environments with High Investment in Employee-Centric Policies and Programs. Among employees with disabilities whose organizations invest heavily in employee-centric policies and programs, average BLISS Index scores rose to within approximately 1 point of the score for employees without disabilities in similarly inclusive environments. These results held true for employees with all different types of disabilities and for intersectional employees: those who both have disabilities and are members of other traditionally marginalized groups (women, certain races and ethnicities, and the LGBTQ community).

- Work Environments with Low Investment in Such Policies and Programs. Among those working for organizations that did not invest significantly in employee-centric policies, the divide between those with and without disabilities was much greater: BLISS Index scores for those with disabilities were 4.5 points lower.

Comparing the BLISS Index scores for PwD working at high- versus low-investment organizations reveals the most dramatic difference in BLISS Index scores uncovered in our research. If low-investment organizations increase the resources they dedicate to their employees, a 23-point jump in the BLISS Index score for PwD is possible.

Investment in employee-centric programs improves inclusion scores across the board. People who did not identify as having a disability or health condition also had substantially better feelings of inclusion in high- versus low-investment environments: a 20-point jump in the BLISS Index score.

Indeed, many of the policies and programs we assessed in our survey, such as flexible working arrangements and well-being programs, are relevant to and beneficial for all employees.

We interviewed an IT administrator with dyslexia about his experience at an advertising firm in Singapore. His experience serves as an example of the value of programs that are available to all employees. He explained that it’s difficult for him to process language, and he struggles to internalize long emails, interpret wordy presentations, and concentrate, especially when others are around. Flexible working options, support from his direct manager, and companywide training on DEI topics have helped him to feel more included and productive at work, but most beneficial has been the option to work remotely. Work flexibility, which includes hybrid work, he explained, “is a companywide program. It’s not something specific to me or my team.”

Providing flexible working arrangements to all employees, and not just those with disabilities or health conditions, destigmatizes such arrangements for employees with disabilities and lowers barriers to access.

Providing flexible working arrangements—such as hybrid work or flexible scheduling—to all employees, and not just those with disabilities or health conditions, destigmatizes such arrangements for employees with disabilities and lowers barriers to access. A universal arrangement also frees PwD from the requirement to submit medical documentation or other such paperwork to justify their need for flexible work, further reducing the burden on them and any stigma associated with such arrangements. And BCG’s extensive research on what workers value and how to retain talent highlights the importance of flexibility for both desk-based and deskless workers. Many find that flexibility, in terms of place or time, helps them balance responsibilities at home and at work. For PwD, like all other employees, this is a logical and equalizing arrangement.

Our survey revealed the benefits of investing in employee-centric policies and programs:

- It improves disclosure rates: 81% of PwD in high-investment organizations have disclosed their disability or health condition to their employer whereas just 67% of those in low-investment organizations have done so—a 14-percentage-point difference.

- It enables more PwD to be their authentic selves at work, with 86% of PwD in high-investment organizations versus 49% in low-investment organizations—a 37-percentage-point gap—stating that they can be their authentic self at work.

- It reduces attrition risk for all employees by more than half—but with an outsize impact on PwD, whose reduced risk is 1.5 times greater than that of nondisabled employees.

Providing Mentorship

Mentorship programs can lead to a paradigm shift for PwD. Russell Shaffer, the executive vice president for strategy and programs at Disability:IN, described the impact of mentorship programs for employees with disabilities:

“Historically, employment for people with disabilities has focused on ‘get someone a job’ instead of ‘put someone on a career path.’ And those are two entirely different outcomes. Having a mentor says to the individual, the organization and its leaders notice me, they notice my aspirations, and they are matching me with someone who can help me get there.”

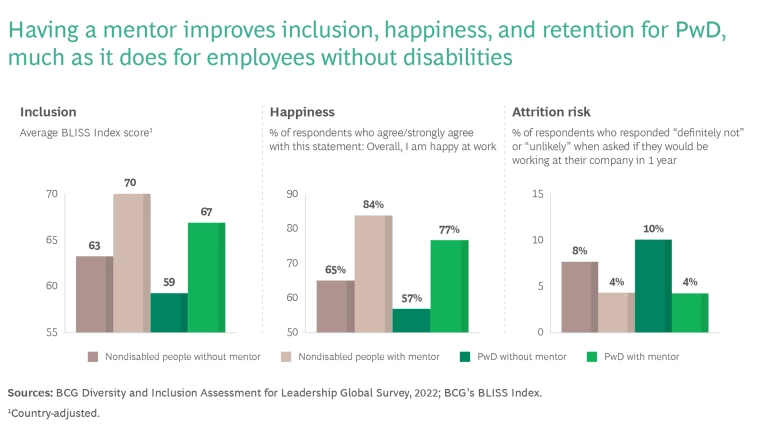

Our research shows that mentorship brings many benefits:

- Feelings of Inclusion. Having a mentor improves feelings of inclusion for employees with disabilities. The average BLISS Index score for mentored PwD is nearly 8 points higher than that of disabled employees without a mentor.

- Happiness at Work. Mentorship improves happiness at work: 77% of PwD with a mentor say they are happy versus 57% of PwD without a mentor.

- Risk of Attrition. PwD with a mentor report less than half the attrition risk: 4% with mentors say they are likely to leave within a year, but 10% without a mentor say they are likely to leave within that time frame.

Another benefit: PwD who have a mentor are more likely to disclose their disability or health condition to their employer—79% of PwD who have a mentor have disclosed their disability compared with 68% of PwD who don’t have a mentor. This suggests that having an advocate who supports and coaches them makes people feel comfortable about revealing a disability or health condition.

At its best, mentorship builds relationships.

Mentorship has indirect benefits that go beyond direct career advancement. A mentor can serve as a sounding board and source of support; help a mentee navigate work issues, such as the process for seeking reasonable accommodations; and coach toward better performance. At its best, mentorship builds relationships, which has cascading benefits for the individual tackling the extra work of being an employee with a disability, such as HR processes, private conversations with direct managers, dealing with bias from peers, and, often, dealing with the day-to-day impact of a disability.

By increasing the uptake of organization-sponsored mentorship programs and training mentors on disability inclusion, organizations can make substantial progress in improving the sense of belonging and inclusion for their employees with disabilities.

The quality of mentorship programs, including how pairings are made and mentors’ aptitude, is important:

- Matching mentors and mentees solely on the basis of having a disability is not sufficient. Instead, organizations need to ask employees about the dimensions important to them for a mentor match, including professional interests and ambitions.

- And mentors can benefit from training on best practices for people development. Disability inclusion training can be an asset to mentors who don’t have the experience of living with a disability.

Done well, mentorship can transform the experience of PwD in the workplace: improving feelings of inclusion, increasing retention, and helping PwD perform better in their current role and progress in their careers. This creates a virtuous cycle: nurturing a pool of leaders with disabilities who can share their experiences, advocate for other employees with disabilities, serve as example of success to more junior PwD, and act as mentors to future generations.

Authors of this report can personally confirm the benefits of mentorship. Brad Loftus, a managing director and senior partner at BCG, became a mentor for Hillary Wool, a BCG principal, after she acquired a disability during her second year with the firm. Amid this challenging experience, she worried about the impact on her career. But she found a shared bond with her mentor, who, like Wool, is an ambulatory wheelchair user, and she says that their relationship has helped her think expansively about her path toward leadership in the firm.BCG’s Journey Toward Inclusion for Its Employees with Disabilities

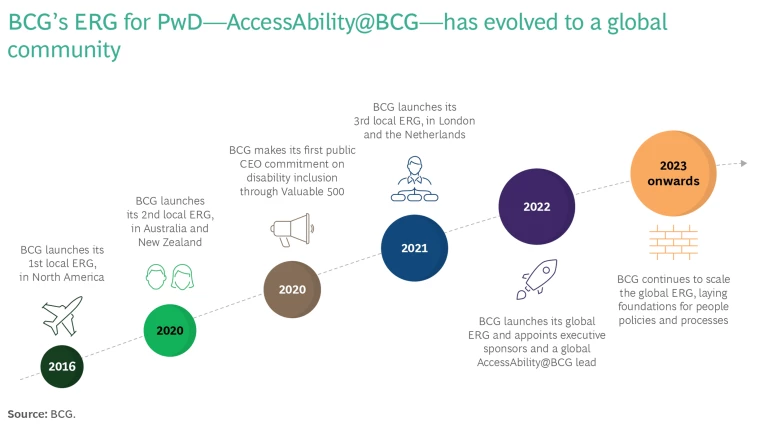

In pursuit of these goals, we have hosted local and global events to raise awareness and promote education and launched employee resource groups (ERGs) to promote affiliation and facilitate mentorship. We are working to ensure a systematic reasonable-accommodations process across all our offices.

Our global ERG for PwD, AccessAbility@BCG, is integral to disability inclusion within our firm. AccessAbility@BCG is open to BCG employees who have a disability, who are caregivers to someone with a disability, or who are allies of PwD. The group provides a space for affiliation, resources for awareness and navigation of people processes, and connection to mentors.

Offering Reasonable Accommodations

When people with disabilities request reasonable accommodations—such as particular equipment or software, flexible working arrangements, or adjustments to their physical environment—and those requests are approved, BLISS Index outcomes improve significantly: a 17-point increase over the scores of PwD whose requests for accommodations were denied.Indeed, with approvals, the average BLISS Index score for employees with disabilities nears that of employees without disabilities; the difference narrows to just over one point. It’s worth noting that some 77% of PwD surveyed requested at least one accommodation, and of that population, 92% had at least one of their requests partially or fully met.Other research bears out the benefits of workplace accommodations. According to the Job Accommodation Network (a service of the US Department of Labor that provides free technical assistance about job accommodations), 75% of employers that provided accommodations deemed the adjustments very effective or extremely effective. They also reported that accommodations were very economically feasible: 56% cost nothing to implement; others cost, on average, $500.Sometimes, of course, requests for accommodations are denied. In those cases, the impact is profoundly negative: BLISS Index scores plummet, falling 15 points below the baseline scores for PwD who do not request accommodations and 18 points below those of nondisabled employees. Attrition risk increases, too, when requests for reasonable accommodations are denied.Why might PwD not receive reasonable accommodations?PwD who have not disclosed their disability are less likely than those who have disclosed to request reasonable accommodations. We found that 75% of PwD who have disclosed their disability status requested and received accommodations, whereas just 58% of PwD who have not disclosed their disability requested and received accommodations—providing further evidence of the link between disclosing a disability to an employer and feeling comfortable to ask for appropriate workplace accommodations. The pattern holds even when there is no legal requirement to disclose disability status to receive accommodations. For example, of respondents based in Japan, 55% of PwD who have disclosed request and receive accommodations compared with 31% of PwD who have not disclosed, and among respondents based in China, 97% of PwD who have disclosed request and receive accommodations compared with 84% of PwD who have not disclosed.The definition of reasonable accommodation varies, based on context, and not every request for an accommodation will fit the definition of reasonable. Employers may consider cost, effectiveness, practicality, and disruption to other workflows and employees in determining what constitutes a reasonable accommodation for an employee with a disability. Given that, a certain percentage of requests will be denied, lowering feelings of inclusion and raising attrition risk. It’s important that employers understand that in denying a request, they may be trading one risk for another.Protections for PwD at work and legal requirements to provide reasonable accommodations to PwD vary among countries.When employees with disabilities do request accommodations, another issue is how to do so.Direct managers play a crucial role. According to research conducted by the Yang-Tan Institute on Employment and Disability, US employees were at least 60% more likely to share the fact that they had a disability with a supervisor than with HR. Because direct managers may be the first point of contact for an employee with a disability seeking to disclose their disability and ask for workplace adjustments, direct managers need training and resources to appropriately manage disclosure, liaise with HR, and implement workplace adjustments.Furthermore, our interviews with employees with disabilities underscored the important role of the direct manager in creating an environment in which employees can safely ask for accommodations and work creatively with their team to find solutions. One employee discussed how her direct manager supports her: “Flareups from my chronic illness can be unpredictable. Communicating and having a flexible game plan with my direct manager has helped us prepare for these unpredictable moments and still meet deadlines. She’s been incredibly supportive.”Organizations need to establish processes to evaluate requests for reasonable accommodations. And for individual accommodation requests, HR personnel, direct managers, and the employee should be involved to determine the effectiveness of the accommodation and consider any changes to the accommodation.Fortunately, best practices have emerged from leading disability inclusion organizations, such as Disability:IN and the Business Disability Forum, and from companies that have instituted successful processes for reasonable accommodations. We spoke with representatives of some of these organizations to understand the critical aspects of a system for reasonable accommodations.The most important principle, across processes, is to foster a sense of trust with employees. Organizations should believe what employees say about their experiences, listen when they express needs, and find creative ways to say yes, whenever possible. This applies to senior leaders and direct managers, not just HR.

Disclosure as an Avenue to Greater Inclusion

The choice of whether to disclose a disability can be an agonizing one: nearly half of our survey respondents who have not yet disclosed said the reason was fear of discrimination and bias. This concern is all the more pressing if disclosure is a precondition to receiving accommodations or if the person regards their disability as an important part of their personal identity.The experiences of those who have disclosed their disability or health condition prove that those fears are well founded. Forty-two percent of those who acknowledged disabilities at work say they have personally experienced discrimination. One respondent told us, “My supervisor and co-workers aren’t equipped to deal with my disability. Disclosing my disability alienates me from my coworkers. They bring it up often. And by doing so, they make me feel separate from the team.”Yet we know from our research that disclosure can have benefits beyond accessing accommodations: among our surveyed respondents, 69% of PwD who disclosed reported that they feel free to be their authentic selves at work, compared with only 59% of PwD who did not disclose. And when employees disclose in environments that are safe and to individuals who are supportive, greater feelings of inclusion result. BLISS Index results prove this point:Individuals in more supportive environments are more likely to have positive experiences following disclosure, leading to greater feelings of inclusion. For example, PwD who work for organizations that have invested heavily in employee-centric policies and programs and have disclosed their disability score 2 points higher on the BLISS Index than PwD who have not disclosed. In low-investment environments, PwD who have disclosed score slightly worse than those who have not (approximately one-half point lower).PwD who reported that their direct manager is supportive when things are difficult at work and who disclosed their disability also averaged 2 points higher on the BLISS Index than those who had a supportive manager but did not disclose.One employee shared the positive experience he had in disclosing his disability at work. “In previous jobs, I felt like I needed to pretend my disability didn’t exist to make others comfortable,” he said. “But at this company, the reception to this conversation has been so warm. In disclosing my disability, I feel like I can be myself, and others opened up to me in response. Talking about my disability has deepened my relationships with my team.”To encourage PwD to disclose their disabilities, organizations need to implement programs that make the workplace more inclusive and that educate leaders and direct managers on disability inclusion.

Recommendations for Organizations

We recommend three key actions for organization leaders.

Invest in Meaningful Employee-Centric Policies and Programs

Whether this is a new or continued undertaking, ensure that the effort is supported at the highest levels of the organization. Infuse disability inclusion and accessibility into policies and programs: set and publish ambitions for disability representation and inclusion metrics and incorporate disability representatives on interview panels. Encourage senior leaders to share their own experiences with disability and health conditions.Start with a focus on education, communication, and affiliation. Roll out organization-wide training on concepts of disability, accessibility, and inclusion, helping employees understand how best to support team members with disabilities. Establish employee resource groups (ERGs) so that those with disabilities or health conditions can connect with one another and the larger community can learn and become allies.

Create Mentorship Programs That Include PwD

Determine whether employees with disabilities are making use of mentorship programs. Mentorship for employees with disabilities can be incorporated as part of a broad program, or it can be specific to employees with disabilities, perhaps as part of an ERG.Be sure to evaluate the effectiveness of mentorship programs, including the matching process and mentors’ role in upward mobility for PwD within the organization.

Provide Reasonable Accommodations

Remember that providing reasonable accommodations is not about lowering expectations for employees with disabilities; rather, it means ensuring that all employees, including those with disabilities, have what they need to be productive, effective, and efficient at work.Put in place a user-centric system that outlines a policy for reasonable accommodations policy and process. Make sure it is clearly and widely communicated, supported by a well-trained team, and funded to eliminate stress on business unit budgets (by, for example, funding reasonable accommodations centrally or budgeting reasonable accommodations into P&L planning). Ensure an end-to-end approach: from the initial hiring process through an employee’s full tenure, make it easy for PwD to ask for and receive accommodations. Message to employees that asking for assistance when needed is a strength. Evaluate requests for accommodations with trust. As needed, consult with medical, occupational health, and disability inclusion experts to ensure that employees receive the most effective and appropriate accommodations.Train direct managers to appropriately handle disability disclosure conversations and to implement reasonable accommodations and other workplace adjustments. Give them the resources they require: education and training to recognize the need for reasonable accommodations and to know how to implement them, for example, and time to support direct reports with the process of requesting a reasonable accommodation and assessing its effectiveness.Consider centralizing the system for reasonable accommodations to aggregate common requests and ensure fair and equitable implementation of accommodations.Evaluate continuously and adjust accordingly.

Get Started

Recognize that your current disclosure data likely provides an incomplete count of disability and that the true number of people with disabilities in your workplace is significant. Still more members of your workforce may be caregivers for people with disabilities.Take action. The data shows that our recommendations for organizations can have high-impact results, making it possible for employees to be happier, more productive and motivated at work, and more likely to stay on the job.