Trends in Corporate-Startup Collaboration

Accelerating market forces are pressuring even well-established companies to innovate and tap new markets in order to stay ahead of the competition. While many corporates have been content to pursue internal, incremental change in response to global competition and disruptive technologies, others have boosted their innovation engines by collaborating with startups. These relationships give corporates access to startups’ creativity, new ways of working, and proficiency with new technologies. In return, startups gain access to corporates’ markets, customers, and industry expertise—and the reputational boost of working with major industry players.

Such relationships often start out very positively, with a heady honeymoon period during which both sides enjoy some early successes. Over time, however, frustration can set in as one or both partners wake up to the reality that they are not achieving all of their hopes and expectations. According to BCG research conducted in Europe, 45% of corporates and 55% of startups are “very dissatisfied” or “somewhat dissatisfied” with their partnerships.

To gather data for this report, we surveyed 187 corporates and 86 startups and conducted a bottom-up analysis of 570 companies in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. We also interviewed more than 30 leaders in the startup ecosystem, including venture capital and private equity investors, startup founders, and executives at public and privately owned companies. They described a complex collaboration landscape in which a company can choose from among various types of innovation vehicles, depending on the company’s size, goals, and expertise. We also identified a number of steps that companies can take to improve their likelihood of achieving long-term success, despite the unique challenges involved in these collaborations. Given the pace of innovation and the huge potential benefits at stake, it is critical for both sides to redouble their efforts to make these relationships work after the initial infatuation has faded.

Increasingly, Corporates and Startups Are Linking Up

To identify promising startups and establish regular working relationships with them as part of an innovation strategy, many corporates have set up one or more types of innovation vehicles—such as corporate venture capital (CVC) or partnership units. The trend has gathered significant momentum over the past decade. In our survey, 65% of corporations reported having had some interaction with startups during the past three years. Oliver Holle, CEO of Speedinvest, has noticed a concerted effort by corporates in recent years to link up with startups: “The number of corporate investors in startups has increased massively. Almost all of our fintech portfolio companies have a corporate investor on board—50% of all startups we are invested in.”

Companies use five types of innovation vehicles in their collaboration efforts: innovation or digital labs, accelerators, corporate venture capital (CVC), partnership units, and incubators.

Companies in our sample of 570 corporates use five types of innovation vehicles in their collaboration efforts: innovation or digital labs, accelerators, corporate venture capital (CVC), partnership units, and incubators. (See “Different Innovation Tools Suit Different Objectives.”)

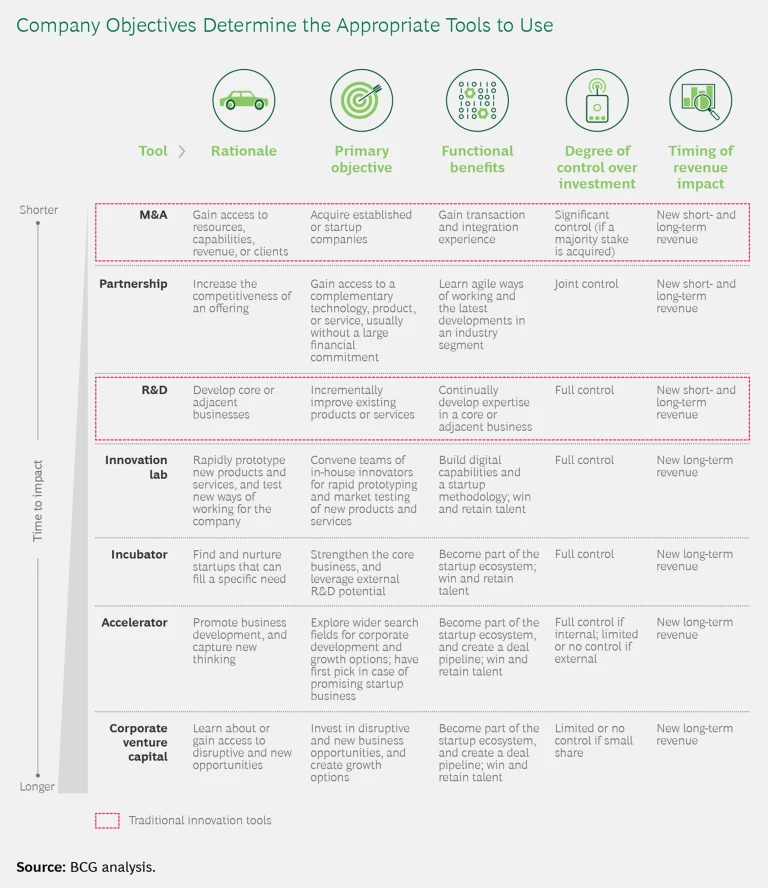

Different Innovation Tools Suit Different Objectives

Different Innovation Tools Suit Different Objectives

The corporate innovation approach should also clarify how to use each vehicle to attain the company’s innovation goals. For example, if a company wants to learn about disruptive or new opportunities, CVC is a good tool. But if it wants to tap quickly into a new revenue source, M&A will be necessary to acquire a controlling stake in a business. A company must also identify when a particular combination of tools will best address specific innovation challenges and how to orchestrate those tools.

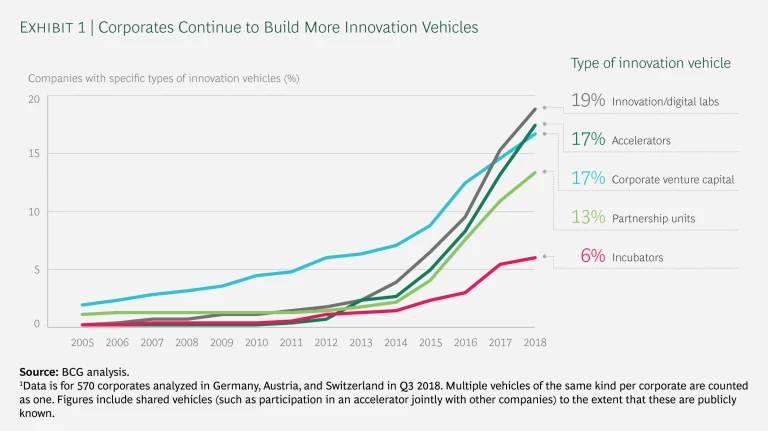

Some types of innovation vehicles are more common than others, however. We found that, at the end of 2018, 19% of corporates were using at least one innovation lab or digital lab, 17% were using one or more accelerators, 17% were using one or more CVC units, 13% were using one or more partnership units, and 6% were using one or more incubators. (See Exhibit 1.)

The most successful corporates don’t just build new innovation vehicles; they also continuously refine the ones they already have. One example of this approach involves the decision by the German insurance company Allianz to transform its incubator, Allianz X, into a CVC unit focusing on strategically relevant digital investments. Another example involves Axel Springer, which operated a joint accelerator with Plug and Play that provided accelerator services to more than a hundred startups. Axel Springer Plug and Play eventually decided to stop taking in new startups; but it continues managing its existing portfolio, thereby freeing up resources for acceleration in a new collaboration, APX, between Axel Springer Digital Ventures and Porsche Digital. Founded in 2018, APX is an accelerator for cross-industry startups.

Corporate Size Matters in Innovation Vehicle Decisions

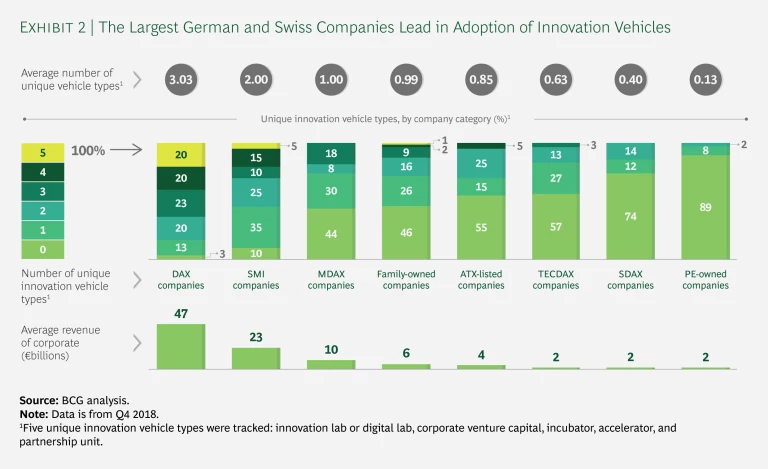

A wide range of companies deploy innovation vehicles, from large public companies such as Daimler, UNIQA Insurance Group, and Swisscom to family-owned businesses such as Viessmann and Hubert Burda Media to companies owned or backed by private equity such as Sivantos and Otto Bock Healthcare. Many companies use several different types of innovation vehicles. (See Exhibit 2.)

The number of vehicles that companies use varies widely depending on company size and industry sector. Not surprisingly, large public companies are more likely than others to deploy innovation vehicles. There are three reasons for this. First, large players have more resources and can afford to place multiple bets. Second, because big companies tend to have entrenched ways of conducting business, they may feel a greater need to explore outside sources for disruptive thinking. Third, investors often pressure large public corporates to demonstrate their willingness and ability to respond to emerging threats.

Of the 30 DAX companies in Germany’s blue-chip DAX index, only one uses no innovation vehicles at all. In contrast, 20% of DAX companies—including, for example, Daimler—use all five types of innovation vehicles. Daimler’s combined CVC and M&A unit, M&A Tech Invest, has made several acquisitions, including the taxi-ordering app Mytaxi. (For more on Daimler’s innovation initiatives, see our 2018 report “How the Best Corporate Venturers Keep Getting Better.”) On average, DAX companies use approximately three types of innovation vehicles. BASF, a leading global chemical company, maintains multiple vehicles, including its Chemovator incubator and a CVC unit, BASF Venture Capital GmbH. “In our fast-moving world, partnerships with young and dynamic companies are essential for the transformation of DAX companies,” says Markus Solibieda, managing director of BASF Venture Capital GmbH.

Companies in Switzerland are, on average, smaller than those in Germany and use only about two innovation vehicles per company. Among the companies listed on the Swiss Market Index (SMI), 90% use at least one type of innovation vehicle, and 5% deploy all five types.

Among the 154 private, family-owned companies we surveyed, 54% reported using at least one innovation vehicle. On average, companies in this category use one type of innovation vehicle per company. Viessmann is among the few such companies that deploy all five types of innovation vehicles. Viessmann’s WATTx incubator specializes in deep-tech companies, and its CVC group consists of two units: Vito One, which focuses on seed capital; and Vito Ventures, which focuses on late-stage funding. The company also has a digital lab (Maschinenraum [“Engine Room”]) and a partnership unit (Innovation Boiler) that directs most of its attention to the Internet of Things, blockchain, and smart climate space technologies.

The average company listed on the Austrian Traded Index (ATX) uses even fewer types of innovation vehicles than family-owned companies do. Only 45% of the ATX-listed companies use at least one type of innovation vehicle, and none of them use all five. Even so, some ATX companies are pursuing different options in this area. UNIQA Ventures (the combined CVE and M&A unit of UNIQA Insurance Group), for example, has multiple startups in its portfolio in health, mobility, smart home, and fintech domains. The company also has an incubator, an accelerator (with about 100 startups on site), and a digital lab.

We also analyzed 132 private-equity-backed companies, only about one in ten of which have as yet adopted any type of innovation vehicle. Private equity firms do support innovation and disruption, but they have traditionally tended to do so organically or through acquisition, says Olof Hernell, CDO of the private equity house EQT Partners AB. “Disruption through innovation vehicles is an untapped opportunity for many companies—if they can afford it,” adds Hernell.

Industries Pressured by Disruptions Are Leading Adoption

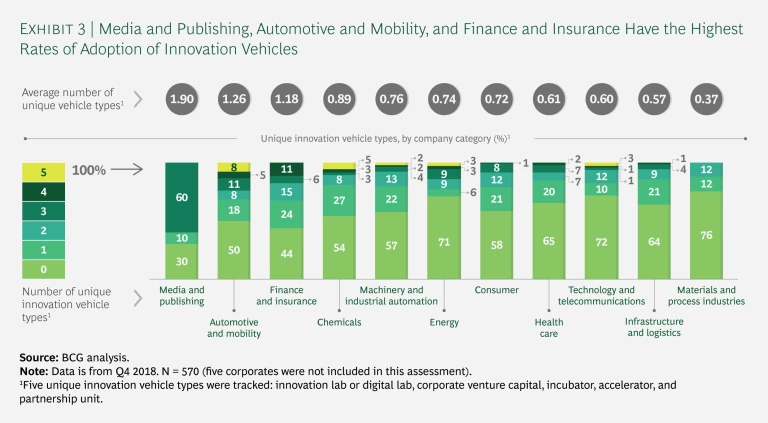

Different industries show huge variations in how extensively the companies in the category use innovation vehicles. Companies in the media and publishing, automotive and mobility, and financial institutions and insurance industries are among the most likely to strike up partnerships with startups. (See Exhibit 3.)

Media companies’ legacy business has steadily declined for the past two decades because of digitization. In response to this threat, many have sought to transform their business model. About 70% of surveyed media and publishing companies use at least one type of innovation vehicle, and 60% have at least three types in place. Successful players in this industry are now on track to digitize their offering. Axel Springer, for example, increased the percentage of its revenue that comes through digital channels from almost 0% in 2000 to more than 70% in 2018. It is now the largest digital publishing house in Europe.

Companies in the media and publishing, automotive and mobility, and financial institutions and insurance industries are among the most likely to strike up partnerships with startups.

In the automotive and mobility industry, 50% of companies use at least one type of innovation vehicle, 5% use four types, and 8% use all five types. The push for innovation in this industry is due, in part, to momentum toward electric vehicles and autonomous driving. New entrants such as Tesla and established tech players such as Alphabet are forcing incumbents to jump-start their programs by tapping startup expertise. The sharing economy and the declining need that people who live in European cities feel to own personal cars are intensifying the pressure on companies in this industry to innovate products and business models.

Among financial institutions (FI) and insurance companies, 56% use at least one type of innovation vehicle, but only 11% deploy as many as four types. As Dr. Andreas Brandstetter, CEO of UNIQA Insurance Group says, “FI and insurance are not well known for their innovative approaches.” The industry’s competitive landscape is changing, however, as fintech startups roll out customer-centric offerings. The Germany-based digital banking startup N26, for example, became a unicorn in 2019 and today is valued at $2.7 billion. Such success stories exert intense pressure on FIs and insurance companies to invest aggressively in innovation vehicles. Allianz X recently increased its fund size to around €1 billion, making it one of the largest startup investment vehicles in Europe.

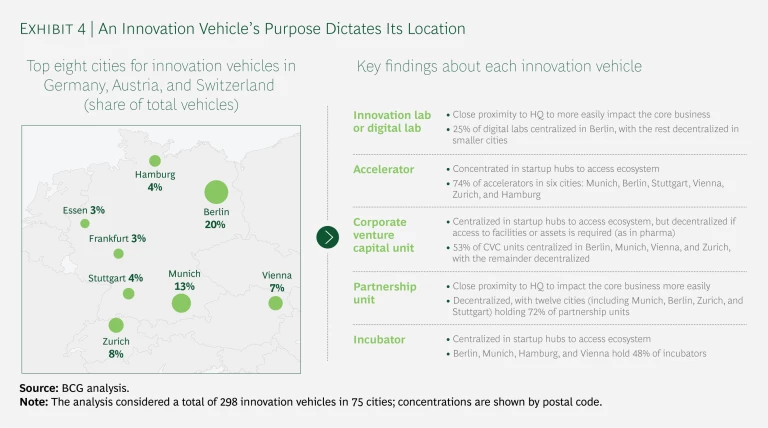

An Innovation Vehicle’s Purpose Determines Its Location

There is also some correlation between the type of innovation vehicle and its location. (See Exhibit 4.) Innovation vehicles that focus on transforming the core business—as many digital labs and partnership units do—are usually geographically close to corporate headquarters because they require easy access to corporate assets and business units.

In contrast, other innovation vehicles need stronger access to the startup ecosystem—talent, business angels, investors, exchanges with other startups—so they tend to be concentrated in startup hubs such as Berlin, Munich, Zurich, and Vienna. Accelerators and incubators fall into this category. As for CVC units, these may or may not be located near headquarters, depending on how much access to corporate assets the startups require and whether the CVC is focusing entirely on a financial objective.

Having Coordinated Objectives Enables Some Partnerships to Flourish

Over the past ten years, corporates have benefited from startup collaborations in myriad ways, such as by adopting agile ways of working, applying different tools (such as Slack and Zoom) in support of new ways of working, encouraging greater collaboration, embracing an entrepreneurial mindset that is less averse to risk and accepts that some failure is necessary in pursuit of innovation, and adopting innovative product features to acquire customers. With regard to agile working, for example, Sivantos and audibene organized 12-month rotations of employees to strengthen cooperation.

Of course, these relationships must meet the needs of both partners. “Startups and corporates do often have different objectives; this is what both parties need to understand and internalize,” says Dr. Ulrich Schmitz, CTO of Axel Springer. Startups enter into these relationships to increase their sales opportunities and market access to a large customer base and to leverage the relationship to bolster their reputation in the market. “We have drive, dynamism, flexibility. They have mass, capital, range. If we want to go out and scale our impact, we have to go to corporates,” says Goran Maric, CEO of Three Coins, a social startup that develops educational products to increase its users’ financial competency.

One success story—from both partners’ perspectives—involves Axel Springer’s decision to take a controlling stake in StepStone, a digital job market and talent recruitment company. While StepStone was striving to increase its sales and market share, Axel Springer was building up its digital capabilities. After taking control of StepStone in 2009, Axel Springer pursued an acquisition strategy to grow and scale the business. It purchased Totaljobs Group in 2012, followed by YourCareerGroup and Saongroup in 2013, Jobsite in 2014, and ICTjob and CareerJunction in 2015. From 2009 to 2016, the company’s revenue grew from about $100 million to $362 million, a compound annual growth rate of roughly 20%. Besides satisfying StepStone’s market share targets, Axel Springer’s buy-and-build strategy strengthened its own digital capabilities and facilitated its broader digital transformation. In conjunction with an accelerator and a partnership with Samsung Electronics, Axel Springer successfully steered its business toward digitization.

Most Collaborations Don’t Meet Expectations

Ironically, success stories like the one involving Axel Springer and StepStone may have encouraged many corporate-startup collaborations to delay a necessary reckoning. Many participants in such collaborations realize that their relationship is not yielding the returns they expected and is not delivering on its full potential. In our survey, 45% of corporates and 55% of startups rated themselves as either “somewhat dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied” with the relationship. In contrast, only 8% of corporates and 13% of startups rated themselves as “very satisfied.” Lea-Sophie Cramer, founder and CEO of Amorelie, puts it this way: “Only 5% of collaborations work well; 95% either do not work at all or are just mediocre. The reason lies in the huge difference between startups and corporates in terms of ideas, expectations, and people.”

Ironically, success stories like the one involving Axel Springer and StepStone may have encouraged many corporate-startup collaborations to delay a necessary reckoning.

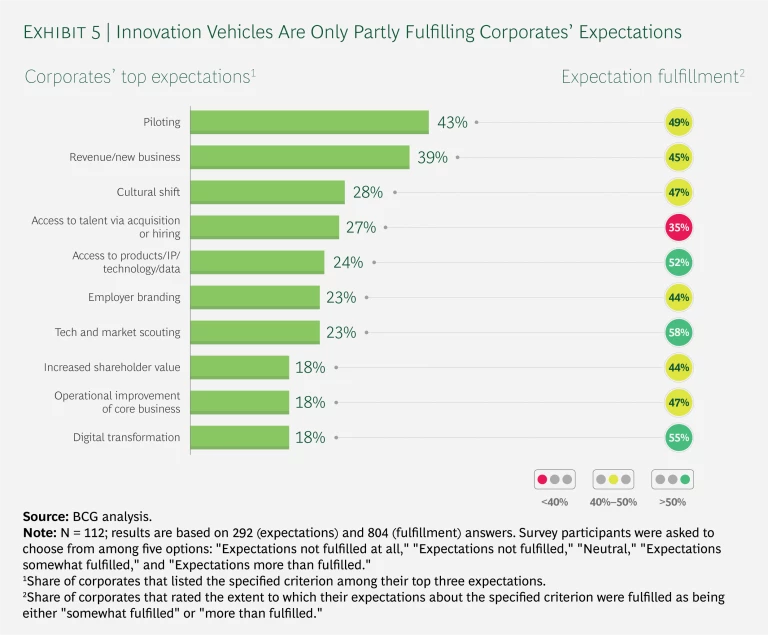

Less than 50% of corporates reported that the top three expectations that corporates have for their partnerships—piloting, more revenue or new business, and a cultural shift—have either been “somewhat fulfilled” or “more than fulfilled.” (See Exhibit 5.) Corporate expectations that have yielded the highest percentages of fulfillment are technology and market scouting (58%), digital transformation (55%), and access to products, IP, technology, and data (52%).

Although 46% of corporates said that collaborating with startups had a “considerable impact” or a “major impact” on their core business, the remaining 54% described the experience as having had a “slight impact,” a “limited impact,” or “no impact”–leaving ample room for improvement in these relationships. The reported level of impact held steady across all five areas that we measured: steering and governing, people and communication, entrepreneurial mindset, ways of working, and financial return.

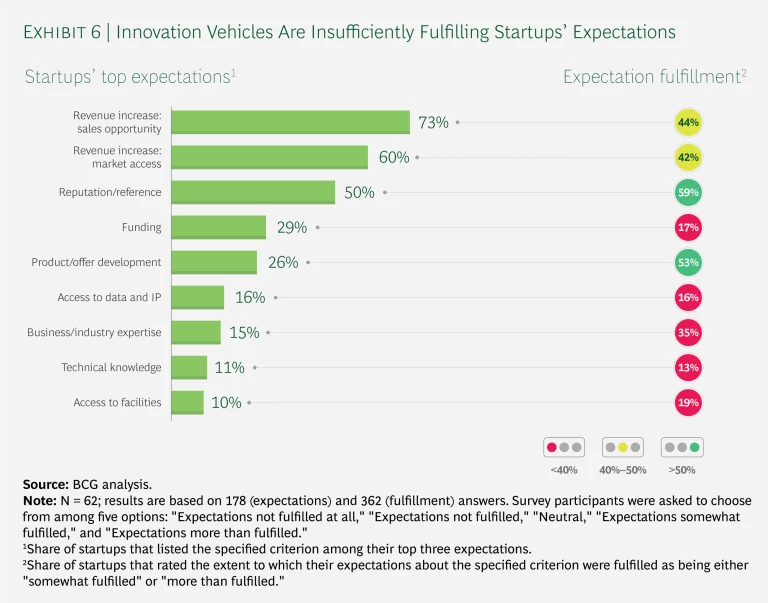

Overall, startups are even less satisfied than corporates with the outcomes of their collaborations: 55% of them described themselves as either “somewhat dissatisfied” or “very dissatisfied.” Broadly speaking, startups engage with corporates to leverage the “unfair advantage” that a strong corporate partner can supply. Startups want to gain access to their partner’s sales opportunities and market, and they want its reputation to rub off on them. Unfortunately, in many cases, these broad expectations go unfulfilled. Less than 50% of startups said that their expectations were “somewhat fulfilled” or “more than fulfilled” in terms of sales opportunities (42%) and market access (44%). More encouragingly, 59% said that their desire for reputation or reference was satisfied at these levels. (See Exhibit 6.)

Although those results are far from stellar, other expectations are fulfilled even less often: four of startups’ top nine expectations are fulfilled less than 20% of the time. Surveyed startups are highly dissatisfied with the technical knowledge, access to data and IP, and facilities that corporates have given them, and with the funding support they receive.

Expectations vary depending on the startup’s maturity. Preseed startups are most in need of a reputational boost and support in developing their offering. Meanwhile, seed-funded startups are very concerned about follow-up funding and gaining market access to increase sales. The most mature series A and B startups need to boost sales further and often want to improve their offering by using the partner’s expertise and production facilities.

Pinpointing Reasons for Dissatisfaction Can Help Avoid Misunderstandings

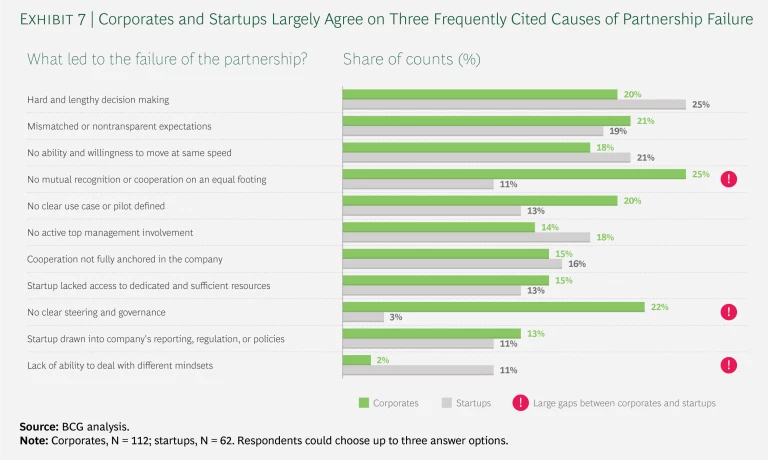

To make corporate-startup partnerships work in the future, both sides need to understand what is not working today. Although they do not universally agree about what factors are most responsible for causing partnerships to fail, startup and corporates do concur in identifying three factors as being comparably important: hard and time-consuming decision making, mismatched or nontransparent expectations, and inability or unwillingness to move at the same speed. (See Exhibit 7.)

Each side also lists several reasons for failure that the other does not. While startups cite corporates’ inability to adapt their mindset and culture as an impediment, corporates are dissatisfied with the startups’ inadequate appreciation and lack of clear steering and governance.

To make corporate-startup partnerships work in the future, both sides need to understand what is not working today.

Increasingly, however, corporate-startup collaborations are paying more attention to these issues in order to head off problems down the road: “It is key to put yourself into each other’s shoes to understand the other party’s position and prevent mistakes up front. We always ask ourselves, ‘What could the corporate want from us?’ before the first meeting,” says Goran Maric. Corporates express similar insights. “The most successful collaboration is grounded in each side’s understanding of where they really excel and how they can deliver benefit to each other,” says Christoph Keese, CEO of Axel Springer hy GmbH, the company’s digital transformation unit, and the author of Silicon Germany.

Three Factors for Success

Every collaboration presents its own unique challenges and opportunities. Nevertheless, we have identified three approaches that can help partners in any collaboration get more out of the relationship: have a clear, shared rationale for the collaboration; adopt an investor mindset; and create links to the core business. Although our survey focused on Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, we have observed similar relationship patterns around the globe in our work with clients. Moreover, all three approaches apply to both the corporate side of the partnership and the startup side.

Have a Clear, Shared Rationale for the Collaboration

Before entering into any agreement, both sides need to ensure that they share a rationale and a consistent set of expectations for the deal, agree on the resources and expertise that each will bring to the table, and align on the rules that they will follow to deliver on those expectations. “The context for why both parties enter into a collaboration is extremely important so that the long-term vision evolves correctly for both sides,” notes Max Viessmann.

Aligning on the rationale for a collaboration is trickier than it might seem. “Corporates tend to have limited visions for their future, as they are stuck in their daily operations. In contrast, startups often tend to think aggressively toward the future, and so focus on market disruption. Sitting together and aligning on a common vision is key,” says Paul Crusius, managing director and cofounder of audibene.

To this end, transparency is vital. For example, Amorelie conducts vision workshops with potential partners prior to initiating any kind of intercompany collaboration. Lea-Sophie Cramer of Amorelie notes that those workshops are extremely valuable for achieving alignment with the potential partner on a common goal. Celonis applies a similar approach, conducting value creation workshops that CTO Martin Klenk says help build a cooperative environment.

We have identified four basic rationales that corporates often have for choosing to partner with startups: protect, optimize, transform, and grow. The first two rationales relate to developing the corporate’s existing or core business, while the last two relate to developing and growing new business.

We have identified four basic rationales that corporates often have for choosing to partner with startups: protect, optimize, transform, and grow.

Protect. In many instances, corporates can leverage startups to protect their core business against disruption. The idea is not to transform and move away from the existing core business, but to build new business models, products, or services that support and protect the core business. The corporate usually controls the startup as majority shareholder, to ensure the startup’s commitment to it. The corporate may achieve direct control either by acquiring the startup or by building it in an incubator or an innovation or digital lab.

For example, Otto Group founded the fashion and technology startup AboutYou in an effort to attract a new generation of young customers who shop almost exclusively online, while continuing to appeal to Otto’s existing base of customers who shop using both catalogues and the internet. Appealing to both sets of customers is critical to Otto’s strategy because, although the legacy business is likely to persist for decades, the AboutYou model will probably eventually supplant the traditional business model.

Otto treated the startup as a strategic investment and gave it logistical support and space to store items, which enabled AboutYou to scale much faster than it could have done on its own. Otto also gave AboutYou’s founders operational freedom, recruited board members who had experience in the startup ecosystem, and welcomed external investors such as SevenVentures and Bestseller A/S to expand the customer base, gain market share, and enter new markets.

Optimize. Corporates can cooperate with startups to optimize the business in areas such as R&D, marketing and sales, and operations. In these cases, corporates act as clients of the startup and work with it toward an innovative solution to a very specific problem. Such partnership arrangements tend to be nonexclusive (often orchestrated by a partnership unit) and may or may not include a CVC investment. The startup’s main goal in entering this type of partnership is to land large, well-known clients early on to boost its reputation, market access, and sales.

For example, former BMW and IDEO employees founded ProGlove in 2014 with venture capital funding. They developed, designed, and tested their products in conjunction with BMW at the company’s Dingolfing plant in Germany. ProGlove’s wearable products contain embedded sensors and scanners that enable staff to perform warehouse processes faster and more safely by eliminating the need to pick up a scanner repeatedly. As a result of this collaboration, BMW’s global spare parts distribution center is operating at a time savings of up to 4,000 minutes per day.

Transform. A corporate can use a startup’s outsider mindset and new skills to transform and move away from its core business. André Schwämmlein, the founder of FlixBus GmbH, says that “by partnering with startups, corporates are able to change their culture and adapt to new ways of working. Corporates see the need to brace themselves against the pressure of Silicon Valley tech giants and do so by leveraging startups.” Given that the startup has the task of transforming the corporate’s core, the corporate usually wants to exercise direct control over the startup—such as through incubation or internal acceleration.

For example, Viessmann is on track to become a next-generation family business by transforming itself from a manufacturer of heating systems into a company that provides full-fledged, sustainable climate solutions. To achieve this ambitious vision, the family firm is leveraging all five types of innovation vehicles. It has partnered and invested in a multitude of promising startups, including gridX and Building Radar, through its own venture capital firms, Vito Ventures and Vito One. Meanwhile, to enhance the transformation of its core, it has built companies like Statice and Snuk from scratch through its company-building firm WATTx. “Helping early-stage companies to iterate their product as a lead customer sometimes leads to close strategic partnerships,” says Viessmann Group co-CEO Max Viessmann.

Viessmann understands that making a successful transformation involves assembling many puzzle pieces—and that an organization needs a team to put those pieces together. The company founded V/CO for this purpose in 2017. V/CO oversees all digital diversification and innovation activities and ensures proper integration of all innovations into Viessmann. To transform the core, a corporate needs some partners that provide radical innovations and other partners that bundle such innovations while keeping the overall rationale in mind.

To transform the core, a corporate needs some partners that provide radical innovations and other partners that bundle such innovations.

Grow. Corporates can work with startups to grow into areas adjacent to their core businesses. In this case, the corporate may acquire the startup for its new service, product, or business model, or it may test the waters first by making a minority CVC investment. If the corporate finds the startup at an early stage of its development, the corporate may incorporate the startup into its accelerator prior to acquisition. It can then integrate the newly acquired firm into its existing business or let it operate as a standalone business unit. Increasingly, however, corporates are building ventures themselves to drive growth.

Airbus started UP42 in 2018 as a joint effort with BCG Digital Ventures to help develop the growing geospatial solutions market. UP42 is an open developer and marketplace platform for building, running, and scaling geospatial products. The platform offers access to earth observation and terrestrial data, provides data processing algorithms, and gives developers the infrastructure they need to run their code. UP42 benefits greatly from the “unfair advantage” that Airbus grants it—specifically, access to high-quality satellite images and tremendous domain experience built over decades—and it complements these key assets with external data and analytics to provide a comprehensive environment for geospatial solutions.

Adopt an Investor Mindset

Thanks to the work being done by their CVC units, many corporates are developing a more critical investor approach. Even so, most still lack the investor mindset of a private equity or venture capital firm on such points as managing startup portfolios, setting milestones, and establishing risk management guidelines. Some corporates may have M&A units, but operating them is unlike evaluating and investing in firms whose size, price tags, and deal execution speed are on a different scale. Often a lack of discipline has led corporates to pursue deals at the expense of serving clear-headed investment expectations.

The collaboration between audibene, the largest online retailer of hearing aids, and Sivantos, a leading global manufacturer of hearing aids, shows how much an investor mindset matters for success. EQT, a Swedish private equity group, was a mediator and investor in the arrangement. EQT had specific, aggressive goals for the corporate-startup relationship, but it was also pragmatic—driven toward speedy value creation and indifferent to corporate politics. “We would never have started a collaboration with Sivantos if EQT had not been there to bring its investor mindset to the table,” says Paul Crusius.

Moreover, EQT—which as a private equity firm naturally plans to sell its stake at some point in the future—offered the startup’s founders a realistic exit strategy. That, in turn, encouraged them to team up with Sivantos and to keep building the business as an independently operating part of the company. Ultimately, the deal gave audibene the freedom to drive its own business forward, says Crusius.

Among the steps that corporates can take to develop an investor mindset, five stand out: define clear investment guidelines; sign a letter of intent establishing responsibilities and decision rights; install active governance and fast course correction capabilities; grant the startup access to required resources; and accept that some partnerships will fail.

Define a clear investment rationale and appropriate guidelines. Corporates and startups should develop clear investment guidelines (a memorandum of understanding, for example) prior to confirming the investment. Such guidelines will help them decide whether to enter into a partnership in cases where a shared rationale for the deal provides an objective argument in its favor. The guidelines should take into account such soft (subjective) factors as “Do the two partners connect with each other?” and “Is there a strong project sponsor on the corporate side?”

Hard (objective) factors include agreements on metrics and milestones. Settling on KPIs, timelines, and milestones up front will help both sides determine whether a partnership is failing and, if so, how they can end it. Suitable investment guidelines depend on the deal’s specifics and the startup’s stage of development.

Formalize responsibilities and decision rights. On the basis of the agreed investment rationale and guidelines, the partners should create and sign a letter of intent that lays out responsibilities and decision rights. Who decides what? When can each partner act independently? When do they need to coordinate and align on decisions? In addition to clarifying responsibilities and decision rights, the agreement expressly acknowledges what each party brings to the table.

The partners should create and sign a letter of intent that lays out responsibilities and decision rights.

“It is key not only to create a tangible investment rationale, but also to clearly communicate the objectives and specific outcome of a collaboration. Both parties should therefore set up and sign a letter of intent regarding the collaboration to make expectations clear,” notes Stefan Winners, member of the board at Hubert Burda Media.

AboutYou CEO Tarek Müller echoes this view: “The agreement guarantees operational freedom for the startup. As long as the founder team operates in line with the agreement, they have to be free to decide what to do, whom to hire, how to spend money—and to advance business as they desire.”

Install active, adaptable governance to suit startup needs. Corporates and startups need to monitor KPIs regularly against their mutual targets so they can correct course and realign promptly if necessary. Reporting obligations should not exceed what is truly necessary, however; otherwise, processes will slow down and disagreements will fester. Corporates must accept that different rules apply to startups for functions such as legal, compliance, and accounting. “You have to ask yourself when looking at reporting, what is a must-have and what is nice-to-have. You do not want to put unnecessary pressure on startups,” says Dr. Jan Kemper, managing director and CFO at Omio. Klaus Entenmann, president and CEO of Daimler Financial Services, adds, “a corporation’s regulatory requirements and processes need to be adapted to a startup framework in order for both to be successful.”

Grant the startup access to required resources. A corporate should be ready and willing to make additional investments and devote other nonfinancial resources to a startup when the need arises or when well-defined business opportunities present themselves. Without quick decision making and funding transfers, both the startup and the corporate could miss out. Such resources need not come from the corporate itself. One alternative is for the corporate to open the partnership to new players to add financial and strategic value—as when VW invited Daimler to take a stake in Heycar. VW and BCG Digital Ventures jointly founded Heycar, an online car portal, to build a next-generation car-buying experience in Germany. But in order to scale the startup faster and further, VW invited additional strategic investors to participate. In late 2018, Daimler took a 20% stake, helping to position Heycar as a high-quality, brand-neutral platform.

Accept that some partnerships will fail. Most startups don’t succeed. Corporates must accept this and be willing to pull the plug and divest when conditions warrant their doing so. This reality is difficult for many corporates to accept, but taking risks and cutting losses are essential features of the startup culture.

One way for corporates to manage and spread risk is by taking a portfolio approach to their partnerships, placing multiple bets (as private equity and venture capitalist investors do). By treating their investments in startups as portfolios, corporates can distribute the risk that they are willing to take—a crucial tactic, given that most startups do not survive long enough to reach maturity. For a very large corporate, taking this approach might mean investing in 30 to 40 startups per year.

With the right KPIs and goals in place, corporates can decide whether to continue the partnership or pull the plug—the earlier the better if it isn’t working out. Venture capitalists are brutally efficient at this, but corporate executives are more inclined to delay ending a partnership, in hopes of not losing face, hurting their career, or losing budgeting for the next partnership. “It is especially hard to let go of collaborations that have been communicated to the market,” observes Dr. Jan Kemper.

Create Links to the Core Business

Startups prefer to collaborate with corporates rather than venture capitalists for one reason: they want to secure the “unfair advantage” that corporates give them over other startups. Corporates can grant startups access to sales channels, difficult-to-acquire customers, facilities, data and IP, industry and business expertise, deep technology understanding, corporate networks, and much more—benefits that no purely financial investor can match.

To persuade startups to collaborate, corporates should identify internal capabilities they possess that are highly valuable to startups—and they should be prepared to grant startups access to those capabilities when the time comes. These direct links to the core business and the competitive edge that they create for startups can drive success for both sides. For corporates, the arrangement is far more advantageous than funding or hiring the startup as a service provider would be. Still, corporates must be realistic about the division of responsibilities. “The corporate is responsible for identifying what the startup can do better than the core business. How to transfer this into the core and advance it is the role of the corporate, not the startup. It is a misconception for the corporate to expect that the startup drives the digitization of their core business,” says Lea-Sophie Cramer of Amorelie.

Unfortunately, setting up a link to the core business is difficult—and not always successful—for both sides. Potential impediments include limited buy-in on the corporate side, the inherent complexity of processes, internal regulations, and slow decision making. Instilling the right mindset is vital, since some employees might otherwise resist creating these direct links, especially if they are being asked to help disrupt their own business. “Management must take away the fear of everything that is new from the organization. This requires classic change management and is essential for leveraging the core business,” says Dr. Jan Kemper.

At the same time, corporates need to devote adequate human resources to the project. “You need a critical mass of people willing and capable to understand new business models and interaction with startups. Support from top management is mandatory, but not sufficient to drive change,” says Dr. Ulrich Schmitz. The issue involves not only what to share but also how to share. Ideally a dedicated team and platform will coordinate stakeholders across the enterprise to ensure a smooth, standardized working relationship that does not frustrate startup operations with poor communication and time-consuming approvals. “Corporates need a systematic approach for collaborations—and they need to scale the approach to create a real impact over time,” says Dr. Florian Heinemann, founding partner of Project A.

One example is George, a digital banking platform maintained by Erste Group Bank AG in Austria. George Labs, a digital research and innovation lab, created George as a platform that is open to external partners, service providers, and fintech startups. Its millions of customers can use it to choose various digital banking services.

Corporates also need to institutionalize a clear interface that the startup can use to connect with the core. Corporates do not want to set up new legal processes for each new partnership, nor do they want to have to win over the necessary corporate stakeholders for each new partnership. As Stefan Winners notes, “Prior to investing in or starting a collaboration, the corporate must be sure how to integrate the startup into complex corporate structures.”

Finally, in any technical discussion about linking to the core, remember that the long-term health of any relationship depends on the multitude of casual interactions that occur every day. These can either build up animosity over time or constantly reinforce the value that each partner sees in the other. (See “Establish Mutual Respect.)

Establish Mutual Respect

Establish Mutual Respect

Establishing a strong foundation for a partnership is vital, but so is properly handling day-to-day casual interactions. Such interactions can either continually strengthen the partnership or gradually erode goodwill and trust. Keeping a few fundamentals in mind can help keep the relationship on track:

- Embrace the differences. The rationale for the relationship is that each side brings different strengths to the table. Embrace that and accept the other’s ways of working. On the one hand, corporates must take care not to stifle the startup with corporate processes. On the other hand, startups must accept that corporates cannot match them in speed because they have to manage fully grown structures and large resources. Before formalizing the collaboration, prospective partners should talk to other corporates and startups to get a keener understanding of the inherent differences in the two types of companies.

- Be supportive and enthusiastic. The entire top management team and supervisory board must be fully committed to the partnership, and the partnership must have a specific senior-level champion. In addition, the hands-on junior employees on both sides need to have good chemistry.

- Communicate as equal partners. Avoid power games. Build a shared vision of the future together, articulate it, and regularly make time to discuss your outlook. Mutual appreciation is key. Startups don’t want to be treated as toys—and corporates don’t want to be viewed as graveyards of originality and innovation.

The Future of Collaboration

We asked companies how they think corporate-startup collaborations will develop over the next five years. Interestingly, startups were far more optimistic than corporates: 86% of startups said that they expect the number of partnerships to increase in the next three years, and 55% of corporates agreed.

Looking ahead to the next five to ten years, 51% of corporates and 58% of startups believe that corporates will institutionalize collaboration. More than half of the corporates surveyed want to work with startups, although a large minority may be playing it too safe and still do not fully realize how much they will need to adapt to operate successfully in a faster, more agile digital world. “Our industry is conservative; we never had requests from strategic investors from Germany,” says Dirk Graber, founder and CEO of the online glasses retailer Mister Spex.

We have identified several trends that we believe will drive future partnerships:

- More Radical Innovation. Few corporates can radically innovate on their own, which makes external innovation their best option. Axel Menneking, managing director of hub:raum Tech Incubator at Deutsche Telekom, makes this point candidly: “Often we just cannot develop new technologies in-house at the right speed with the right customer-centric and competitive mindset. That’s why collaborating with startups is so important, even for a large player like Deutsche Telekom.”

- Accelerated Speed of Change. “As the world becomes faster, corporates need more innovations in a shorter time period. It is not possible to accomplish this alone,” says Michael Brehm, managing director and founder of i2x. Dr. Jan Kemper agrees: “Grand developments that pan out over ten years just don’t exist anymore. Change and disruption have become much faster, and long-term investments are becoming increasingly difficult. Therefore, you have to become agile in your way of working as a corporate. This flexibility is brought to the organization via startups.”

- Shrinking Barriers to Entry. Digitization is opening up new markets around the globe, and corporates are increasingly eager to enter those markets. This opportunity, along with abundant funding options through the capital markets, is spurring corporates to partner with startups to protect, optimize, transform, and grow. “The trend will continue. Digitization empowers business models that are easy to roll out and scale. The barriers to entry are low and will progressively become lower still,” says Clemens Müller of the Erste Group.

- Need to Scale Fast. Corporate partners can help startups scale faster than financial investors can, by providing them with an “unfair advantage.” Startups are keenly aware of this. “We like to say: If you want to run fast, run alone; if you want to run far, run together,” says Goran Maric.

- Growing Experience with Collaborations. Corporates have had to deal with a steep learning curve over the past few years, but the experience has helped them gain confidence in their ability to make corporate-startup collaborations work. Dr. Christian Langer, VP for digital strategy at Lufthansa Group, says, “We got used to each other. Startups are now more mature; both parties have a better idea of what they want and what’s possible.”

- Willingness to Cooperate. Corporates are increasingly willing to set aside their rivalries and combine efforts in corporate venturing and other innovation vehicles. In the next five to ten years, 54% of corporates and 53% of startups agree that corporates will combine their efforts in corporate venturing. “Corporates should adopt the same strategy as Softbank and combine forces with other corporates or investors to successfully play in the big league of startups,” Klaus Hommels of Lakestar says. “If something is going well and you want it to go really well, then you need to ask yourself: what ownership structure will help the startup most? Sometimes this implies opening it up to other players,” says Sebastian Klauke, CDO of Otto Group.

Combining the assets of large corporates with the speed and creativity of startups has tremendous productive potential. Moreover, new beginnings have an inherent attraction that brings passionate intensity to many such relationships. But once the honeymoon is over and real life kicks in, the foundation of the relationship must be strong to endure. Today, with their long history of reinvention, European companies have learned valuable lessons about what makes partnerships succeed or fail, and best practices have emerged that show both sides how to make partnerships more successful.

Both sides still have homework to do. Corporates and startups need to develop clear investment rationales, corporates need to adopt an investor’s mindset, and both sides need to institutionalize effective ways to link startups to the corporates’ core business. Collaborating companies must design pilotable use cases, demonstrate added value, and work transparently along KPIs and milestones to ensure a good working relationship.

Accomplishing those tasks will take some hard work, but companies that succeed will be strongly positioned to withstand competitive pressures and market disruptions. As Christoph Keese puts it, “Leveraging startups for innovation is not a new management trend that will be replaced by another trend in a couple of years; it is the new operating system.”