Canada’s industrial sector faces acute labour shortages, with no immediate let up in sight. Mining and related heavy industries have fallen out of favour with younger workers. Urban centres continue to exert a strong draw. And government efforts to ensure growth in skilled trades could take years to deliver impact.

Left unchecked, these shortages could reduce the competitiveness of a sector that accounts for 25% of the country’s gross domestic product and injects $500 billion into the economy annually.

Industrial leaders can reverse this slide. But success will require approaching talent management more strategically than in the past—and making decisive changes now.

Pay Alone Is Not Enough

Average wages for industrial jobs are higher than in almost any other sector—in some cases, $10-$15 per hour higher. Yet, businesses are still struggling to recruit and retain the labour they need. So, if pay isn’t the issue, what is?

BCG has surveyed thousands of industrial workers in the course of its client work, interviewed dozens more and engaged with leaders at some of Canada’s biggest industrial companies. Their insights reveal some hard facts and new realities.

- Knowledge work is outpacing skilled trades in attracting new workers. Over the past decade, the number of working-age Canadians pursuing university education has grown by 20 percentage points. Computer engineering enrollments are up approximately 15% per year since 2012, while mining, mineral and geological engineering enrollments are down 2% per year over the same period.

- Industrial work faces perceptual challenges. Young people tend to view industrial businesses in a less favourable light than other sectors. Mining is particularly challenged, rated the least attractive profession for young Canadians, according to the Mining Industry Human Resources Council.

- Job priorities are changing. What employees are looking for in their careers is different as well. Younger workers want jobs that feel meaningful and purposeful. And those who don’t get what they’re looking for are prepared to walk. Among deskless workers globally, our research shows that 37% are at risk of leaving within the next six months. And employees who are dissatisfied with their managers are two times more likely to exit and three times less likely to recommend an employer.

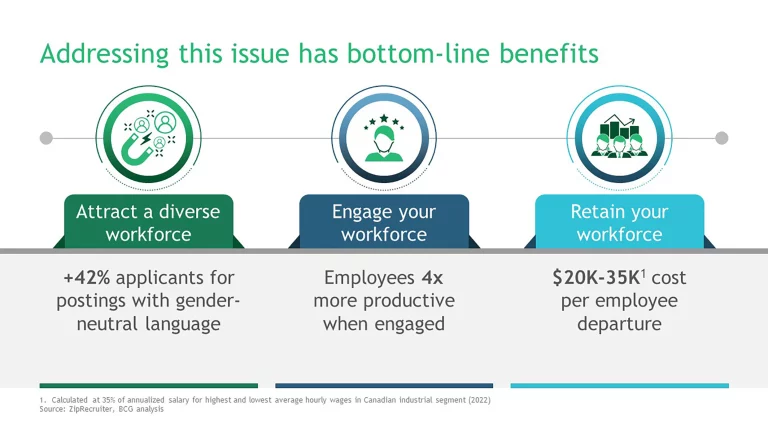

Inaction on these issues is untenable. Industrial companies across Canada are already feeling the sting of talent shortages, with each employee departure costing businesses an average of $20K to $30K. Lost revenues owing to labour shortfalls also add up. In 2022 alone, one Canadian mining company gave up hundreds of millions of dollars in potential revenue because they didn’t have enough staff to run their operations.

Despite these difficulties, a BCG survey found that only 53% of industrial CEOs listed people actions as a top item in their 2023 plan, behind cost (81%), supply chain/operations (65%), and innovation (56%). This prioritization must change. But continuing to approach talent management in the same traditional ways won’t work.

Rebuilding the Industrial Talent Pipeline Requires Going from Old Ideas to Bold Ones

Industrial leaders need to bring fresh approaches that acknowledge current structural realities and drive internal changes that make work attainable, sustainable and rewarding for more people. Here’s how.

Think locally, invest locally: Rather than competing for young, urban professionals, winning players will make their businesses the employer of choice in their local communities, intervening earlier in the pipeline to create flow and training individuals who have already made the area their home. This is the approach a Canadian utility company took, setting up a program to train Indigenous lines people in remote Canadian communities. These workers live in the community, aren’t likely to move away, and once trained can move directly into the company workforce, creating a steady pipeline—a win for local residents, the company and the wider community.

For the pipeline to be sustainable, however, it must be accessible. And this can be a challenge in many lumber, mining and industrial hubs. In Nelson, British Columbia, housing is so tight, many individuals and families have had to move away to seek employment elsewhere. The vacancy rate there is just 0.4%. Accessing quality childcare can be similarly difficult. Approximately 45% of all less-than-school-aged children in Canada live in a “child care desert,” according to a study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. This “desert” is particularly pronounced in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and in pockets of British Columbia such as the Kootenays, all traditional bases for Canada’s industrial activity. Finding creative solutions to these challenges can set industrial leaders apart. One agricultural company went so far as to build a township for its workers. Similarly, a food company that operated in an area with very limited childcare options built their own daycare on premise. Other companies in locations unsuitable for on-site care centres have provided families with deeply discounted subsidies and priority access to facilities in their local communities. These examples reflect two common hardships. But specific barriers to work vary greatly from locale to locale. It’s crucial that leaders spend time on the ground at individual facilities to gain an up-close understanding of needs and determine what types of supports can deliver the most impact.

Unleash the heart of frontline leaders: Most managers want to do right by their people, but few receive the training to provide the empathetic support that our research shows can have the most profound effect on employee satisfaction and retention. Showing heart—which we define as embodying generative leadership, demonstrating genuine care for people, and building meaningful connections—can help employees feel valued and engaged, qualities that have a direct and positive effect on productivity. For example, a transportation company created a specific program focused on helping front-line leaders form more effective relationships with their teams. Initiatives included doubling the amount of time that front-line leaders spent in the field, regularly engaging crews on peer best practices and offering targeted leadership coaching. The initiative proved hugely successful, increasing employee engagement by 7% and trust in leadership by 8%. Another company recognized that haul truck and shovel operators face long hours alone on the job, leading to feelings of isolation and loneliness in some cases; so they are working on solutions to create greater social connection and community.

Industrial leaders don’t leave such improvements to chance. They regularly take stock of workplace health, surveying employees and front-line teams. They also create structures (or nudges) that allow managers to carve out dedicated people time in their calendars, provide managers with the tools and training they need to feel comfortable in their expanded role as coaches and mentors, and offer incentives that reward those who embody generative leadership practices.

Allow schedules to flex and skills to expand: A lack of flexibility and career advancement opportunities are the most common reasons workers cite for leaving their jobs. But while flex work has become a post-pandemic mainstay in many sectors, industrial companies have been slower to adapt, with many assuming the nature of their business precludes such arrangements. But our experience shows that there are many effective ways to inject flexibility. Shift duration, for example, could adjust to include 4-, 8- and 12-hour options. Break lengths and the time between shifts can also adapt. In addition, companies could provide facilitated shift-swapping, job sharing, and blended field/in-office roles to truly unleash flexibility for their workers. The bigger, bolder and broader the flex offerings, the more attractive work can become—giving industrial companies a way to competitively differentiate their workplace cultures and gain a recruitment advantage.

Giving employees a way to grow meaningfully in their careers is also essential. For example, a construction company launched an in-house college and training centre that offered access to thousands of courses. They also introduced custom training and “micro-learning” modules that employees can access from anywhere and in increments that fit their schedules. Employees are actively encouraged to take courses that prepare them for their next career steps, giving them protected time to pursue learning and development, facilitating trainee pairings, and helping them partner with accreditation agencies so they can prep for testing and earn certifications that deepen their experience. The company now the highest ranked in its peer set competitors on employee sentiment.

Elevating talent management to a strategic priority in these ways can pay significant dividends—resulting in greater applicant interest, sharply higher productivity and greater retention. (See exhibit)

Canada’s industrial leaders need to act now before the labour shortage creates an “emptying out” cycle. Winning companies will prioritize talent as an operations-led matter and not simply an issue for HR to solve. This is the time to replace old approaches with bold ones that go beyond the paycheque and emphasize deep community engagement and empathetic leadership practices that make work work for the next generation of industrial talent.