This content was developed in collaboration with Cambridge Associates.

Portfolio diversification is fundamental to effective investment risk management. The term “diversification” traditionally includes asset classes, investment approaches, industry sectors, and geographies. But a vital and often-overlooked dimension of diversification is the people driving portfolio decision making. This dimension of diversification may be especially important in private markets because an asset manager’s deal sourcing is often network driven. Greater gender, racial, and ethnic diversity among asset managers is often thought of as a social initiative when, in fact, it may provide another source of diversification in the pursuit of better risk-adjusted returns.

According to new research from BCG and Cambridge Associates, private equity and venture capital firms whose ownership is predominantly women or people of color may unlock access to differentiated deal flow (i.e., an increase in the variety of investments in a portfolio) for their limited partners (LPs) and other investors. (See “About Our Research.”)

About Our Research

The deals we analyzed included global portfolio investments and equity transactions, but excluded venture debt, grants, and mergers. The deals crossed all industries and investment stages, including pre-seed, seed, and series A, B, and C rounds. We limited our analysis to gender and racial or ethnic diversity in order to mirror the available data. For that reason, we did not investigate other types of diversity, including sexual orientation, military service, and physical ability.

Our data findings were statistically significant, with a 95% confidence level unless otherwise specified.

We followed up our data analysis with a literature review of dozens of previously published reports on asset management trends. We also interviewed diverse asset managers and industry experts to gain additional qualitative insights into diverse-led asset managers’ investing behaviors.

Our analysis of more than 84,000 US-based deals completed by private equity and venture capital firms found that:

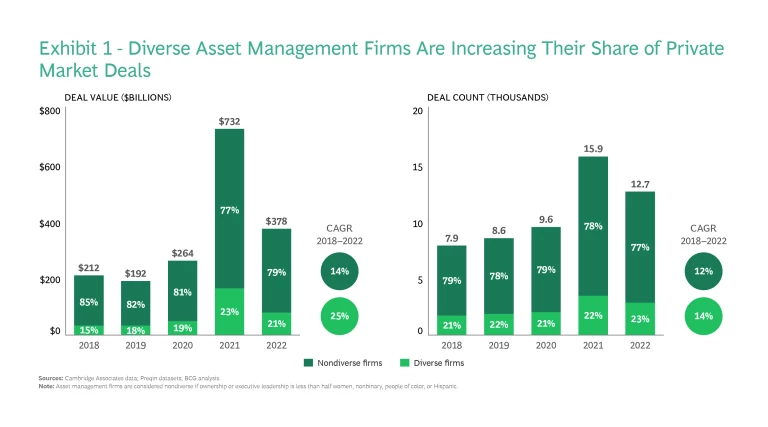

- Diverse-owned firms are increasing their share of private market deals. From 2018 to 2022, the value of the deals led by diverse private equity and venture capital firms grew at 25% annually from a starting point of $33 billion. This is nearly twice the growth rate of deals completed by nondiverse firms. Within the opportunity to invest in differentiated deal flow, the number of private market deals led by diverse firms also grew, by 14% annually, over this same period.

- Diverse private equity and venture capital firms invest in a different universe of deals from that of nondiverse firms. In our analysis, approximately 30% of transactions completed exclusively by diverse-owned firms are not accessed by nondiverse firms. This deal flow represents 7% of all deals and provides the opportunity for differentiated deal flow.

- Diverse private equity and venture capital management teams are more likely than their nondiverse peers to invest in early-stage deals as well as in overlooked companies. Despite a higher relative focus on early-stage deals, which inherently can present a higher risk, diverse private equity and venture capital teams perform as well as their broader peer group of early-stage investors.

To take advantage of the anticipated growth in private markets, asset management firms must continue to seek out competitive returns. In private markets, this often means identifying overlooked but potentially successful avenues for investment. Identifying these “nonconsensus” opportunities may be achieved by intentionally seeking a broader universe of potential deals, especially those that may help diversify portfolio risk.

To unlock access to a broader investment universe, general partners (GPs) may want to consider expanding their talent pipeline and investment teams to include more gender, racial, and ethnic diversity. The same holds for LPs, including asset owners like pension funds, endowments, foundations, and fund of funds. To ensure access to the broadest pool of manager talent possible, asset owners may need to examine their manager diligence framework to avoid unintended bias. (See “Investing Terms.“)

Investing Terms

Deal. A transaction, also commonly referred to as a “deal,” is an investment in a startup or other privately held company by a private equity or venture capital firm at any stage or financing round. A transaction could describe a pre-seed investment, a seed round, or a series A, B, or C round. For the purposes of this analysis, transactions exclude investments in third-party funds or in fund of funds.

Diverse. A private equity or venture capital firm is described as diverse if 50% or more of its ownership or executive leadership is composed of individuals who identify as women, nonbinary, Black, Hispanic, Asian, or Middle Eastern.

Differentiated deal flow. Differentiated deal flow deals are those where the capitalization table (which shows each investors’ equity capital stake in the company) is exclusively diverse-owned firms.

Assessing the State of Diversity in Private Investment

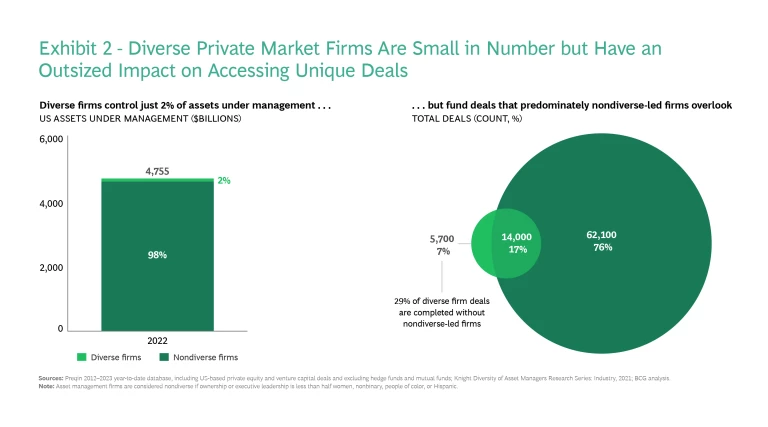

Asset management is one of the least diverse industries within the US financial services sector. According to a 2021 Knight Foundation study, 98% of US assets across all asset classes are managed by nondiverse asset management teams. In private equity and venture capital specifically, the study found that minority-led firms made up only 5.1% of firms and only 4.5% of assets. Women-led firms made up only 7.2% of firms and only 1.6% of assets.

Despite this low representation, when controlling for variables such as fund size and market conditions, the Knight Foundation study found that the returns of diverse asset managers did not statistically differ from their nondiverse peers.

“There’s a misconception that the only reason to invest with diverse owned or led funds is social impact and worse still, that those investments result in lower investment returns,” said Juan Martinez, Knight Foundation vice president and chief financial officer. “Year after year, our research has found that to be wrong. In fact, our research has found that these funds perform at least as well as other funds.”

Until now, little research has been conducted on the differences between the deals completed by diverse and nondiverse private equity and venture firms.

Trends in the Private Market Deals of Diverse Managers

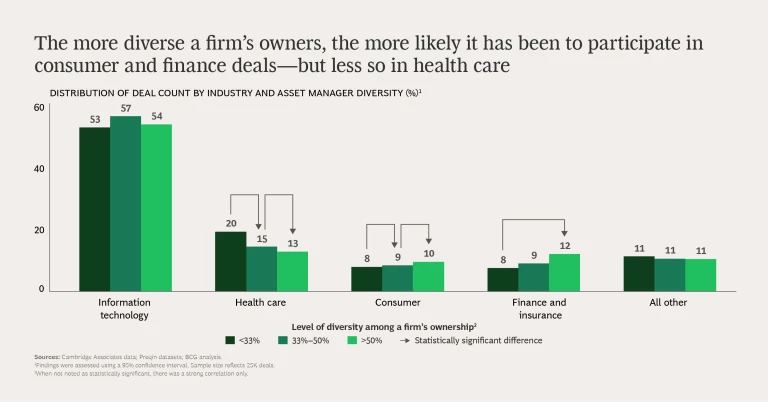

Diverse asset management firms are increasing their share of private market deals. From 2018 to 2022, the value of the deals led by diverse private equity and venture capital firms grew at 25% annually from a starting point of $33 billion—nearly twice the rate of deals completed by nondiverse asset managers. The number of deals led by diverse firms grew by 14% annually in the same period. (See Exhibit 1.)

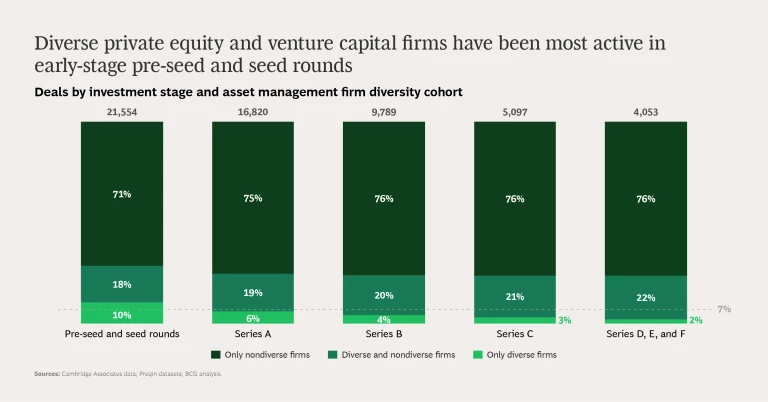

Diverse asset management firms execute differentiated deals. Of the deals we analyzed, 76% were financed exclusively by nondiverse private equity and venture capital firms. Furthermore, 17% of the transactions had deal syndicates with a mix of nondiverse and diverse firms, and 7% were investment rounds completed exclusively by diverse-owned firms. (See Exhibit 2.)

Interestingly, those 7% of deals conducted exclusively by diverse-owned firms represent close to one-third (29%) of all deals conducted by diverse private equity or venture capital firms. Diverse teams’ ability to identify differentiated deal flow represents an opportunity for LPs who want to build a more diversified portfolio and seek additional ways to mitigate portfolio risks, such as sector, manager, or deal concentration risk. Our interviews with asset managers and industry experts confirmed this. “We’ve adopted an investment thesis working with diverse founders who are often overlooked and undervalued,” one venture-capital fund manager said.

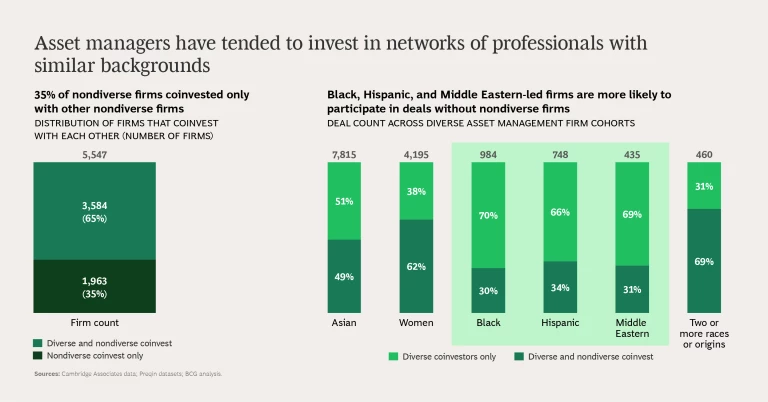

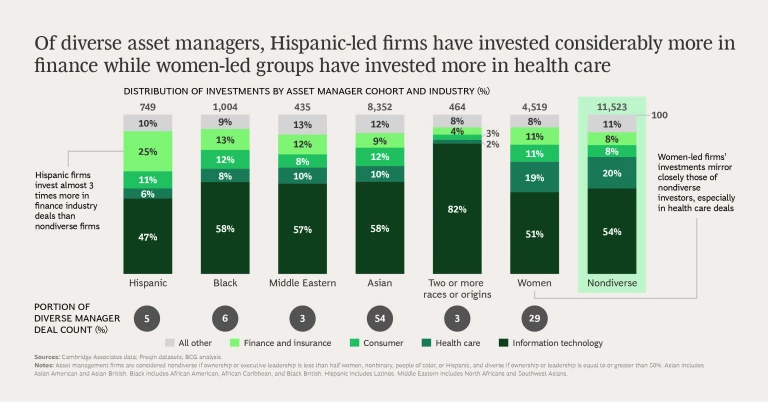

This trend is especially pronounced among Black- and Hispanic-run firms. About two-thirds of their deals lie outside the deal pool of nondiverse asset managers, opening doors to differentiated deal flow in a sphere where they may face little competition.

Through the differentiated lived experiences of their investment teams, diverse-led firms may identify opportunities that others might fail to identify because the latter are not connected to different networks. “I was the first person of color on my firm’s investment committee,” one asset manager said. “Prior to my arrival, the firm would have never selected the deals I proposed. Why? In the venture capital world, you invest in what you know and understand.”

As an example, an analysis of 1,500 fintech transactions included in the deals we studied found that diverse asset managers were more likely than nondiverse asset managers to invest in deals that involved lending or personal unsecured loans that could target historically underserved communities. These types of deals, which may leverage a fund manager’s experience with or connection to certain segments of communities, could help GPs identify potential sources of return that may be less correlated with other investments.

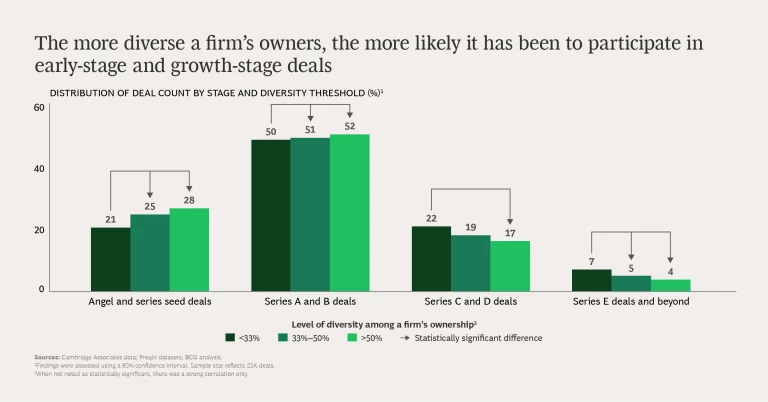

Diverse-led asset management firms are often early-stage investors. The differentiated nature of the deals that diverse private equity and venture capital firms pursue is not the only characteristic that sets them apart from nondiverse firms. Our analysis found that diverse firms have been more active in early investment rounds. In fact, based on our research, 10% of the pre-seed and seed rounds we analyzed were done exclusively by diverse asset managers with no participation from nondiverse managers. Across all rounds, we found it was five times more likely that pre-seed and seed rounds would have diverse-only managers than would series D+ rounds.

Our research and expert interviews revealed that diverse managers may identify these opportunities because of their personal networks and locations outside traditional investment centers such as Silicon Valley. Within our dataset, in addition to differentiated exposure in the early stages, the smaller amount of assets under management by diverse firms may also limit their ability to invest in later rounds. (See the slideshow.)

Asset managers have tended to invest with networks of professionals who have similar backgrounds. Private equity and venture capital firms often team up on transactions with other fund managers, forming coinvestment networks. In the deals we analyzed, we found that 35% of nondiverse private equity and venture capital firms have not coinvested with diverse asset managers. Lack of collaboration may reduce exposure to differentiated deal flow and could reduce the engagement of diverse private fund managers in later rounds. This lack of overlap means that, to access differentiated deal flow, LPs may need to connect and invest directly with diverse GPs.

Perspective for LPs: Steps Toward Accessing Diverse Deal Flow

To deliver competitive returns in an increasingly crowded private equity market, LPs may want to consider seeking new pools of value. Diverse private equity and venture capital firms may provide access to the differentiated deal flow needed to achieve this goal. LPs and investors can improve their potential exposure to this differentiated deal flow by building more diverse teams and using a merit-based manager selection process.

Define a portfolio construction approach. Many LPs consider developing allocations dedicated to diverse or emerging funds, recognizing the risks of this structure. Although diverse manager programs are one approach, these types of allocations over time can be limiting and hinder diverse asset managers’ ability to attract a broader asset owner pool. If LPs do set aside pools of capital to invest with diverse or emerging asset management firms, these firms should be able to compete with all managers from the main capital pool for dollars. “When I’m raising a new fund, I ask investors how I get included in the main asset pool,” one diversity-focused venture capital asset manager said. “If there is a diversity or emerging fund manager asset pool that has an allocation ceiling, I’d rather be included in the main fund to avoid running into artificial limitations.”

Examine the manager diligence framework to avoid unintentional bias. Investors that want to allocate capital to diverse-led asset managers may need to examine their diligence framework to avoid unintentional bias that may screen out diverse firms. Examples include established definitions for work experience or for financial contribution. One option is to look beyond the typical work experience and acknowledge experiences and skills that could contribute to a firm’s ability to find new deal sources. Another is rethinking financial contribution criteria in recognition of the fact that diverse asset managers may not be able to make the same level of capital contribution as nondiverse peers. It is a common practice to require asset managers to demonstrate commitment by providing a specific dollar amount of their own capital alongside that of the investor. Although aligned incentives are important to LPs, an investor may be able to create more equitable access by requiring a capital contribution that is tied to the asset manager’s liquid net worth.

Understand the total portfolio. In addition to incorporating diverse managers across asset classes, LPs can seek to understand how managers throughout their full portfolio are gaining access to differentiated deal flow. It is often not enough to increase diversity by hiring more diverse applicants into lower-level positions. Based on interviews conducted, we found that to gain access to differentiated deal flow, firms need diversity in leadership and investment teams, given the broad network benefits of expanding the investment universe. Asset management firms may consider giving team members the ability to influence or guide investment decisions that shape the portfolio, such as greenlighting seed-stage deals and assessing the qualities of venture founders or seeking out new deals.

Recognize the many types of diversity that could create increased and/or differentiated deal flow. Because of the limits of the dataset of transactions that we analyzed, our research focused exclusively on gender, racial, and ethnic diversity. Other dimensions of diversity include socioeconomic status, sexual orientation, military service, and physical ability. Individuals from each group bring their own perspectives, experiences, and networks, all of which may provide access to differentiated investment opportunities.

People drive portfolio decision making. In private markets, an asset manager’s deal sourcing may be dependent on personal networks. Broader networks may increase the number of investment opportunities. These networks also may expand the potential for differentiated deal flow, mitigating portfolio risk, and enhancing portfolio diversification in the pursuit of improved risk-adjusted return. To put it succinctly, intentionally inclusive investing is responsible investing.

ABOUT CAMBRIDGE ASSOCIATES

DISCLOSURES

This report may not be displayed, reproduced, distributed, transmitted, or used to create derivative works in any form, in whole or in portion, by any means, without written permission from The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. Copying of this publication is a violation of US and global copyright laws (e.g., 17 U.S.C. 101 et seq.). Violators of this copyright may be subject to liability for substantial monetary damages.

This report is provided for informational purposes only. The information does not represent investment advice or recommendations, nor does it constitute an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities. Any references to specific investments are for illustrative purposes only. The information herein does not constitute a personal recommendation or take into account the particular investment objectives, financial situations, or needs of individual clients. Information in this report or on which the information is based may be based on publicly available data. CA considers such data reliable but does not represent it as accurate, complete, or independently verified, and it should not be relied on as such. Nothing contained in this report should be construed as the provision of tax, accounting, or legal advice. PAST PERFORMANCE IS NOT INDICATIVE OF FUTURE PERFORMANCE. Broad-based securities indexes are unmanaged and are not subject to fees and expenses typically associated with managed accounts or investment funds. Investments cannot be made directly in an index. Any information or opinions provided in this report are as of the date of the report, and CA is under no obligation to update the information or communicate that any updates have been made. Information contained herein may have been provided by third parties, including investment firms providing information on returns and assets under management, and may not have been independently verified.

The terms “CA” or “Cambridge Associates” may refer to any one or more CA entity including: Cambridge Associates, LLC (a registered investment adviser with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, a Commodity Trading Adviser registered with the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission and National Futures Association, and a Massachusetts limited liability company with offices in Arlington, VA; Boston, MA; Dallas, TX; New York, NY; and San Francisco, CA), Cambridge Associates Limited (a registered limited company in England and Wales, No. 06135829, that is authorized and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority in the conduct of Investment Business, reference number: 474331); Cambridge Associates GmbH (authorized and regulated by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (‘BaFin’), Identification Number: 155510), Cambridge Associates Asia Pte Ltd (a Singapore corporation, registration No. 200101063G, which holds a Capital Market Services License to conduct Fund Management for Accredited and/or Institutional Investors only by the Monetary Authority of Singapore), Cambridge Associates Limited, LLC (a registered investment adviser with the US Securities and Exchange Commission, an Exempt Market Dealer and Portfolio Manager in the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Ontario, Québec, and Saskatchewan, and a Massachusetts limited liability company with a branch office in Sydney, Australia, ARBN 109 366 654), Cambridge Associates Investment Consultancy (Beijing) Ltd (a wholly owned subsidiary of Cambridge Associates, LLC which is registered with the Beijing Administration for Industry and Commerce, registration No. 110000450174972), and Cambridge Associates (Hong Kong) Private Limited (a Hong Kong Private Limited Company licensed by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong to conduct the regulated activity of advising on securities to professional investors).