Governments around the world tend to be organized in verticals, with various ministries or departments responding to issues that fall within their individual domain. But the world is changing, volatility is increasing, and today’s issues—from the need to maintain cyber security and the advent of artificial intelligence, to poverty and increasing weather extremes—refuse to keep to this structure.

As a result, ministers and department leaders often look to the offices and agencies of the center of government for solutions—for example to the prime minister’s office or the central finance agency. Many countries have seen significant growth in this demand over the past decade.

Yet, the center frequently fails to meet these needs. Obstacles range from ineffective management and inconsistent advice to burdensome reporting requests and bureaucracy that hampers policy delivery.

Our experience shows that centers of government can play five key roles very effectively, building a more capable public sector, if they follow four principles.

Our experience shows that centers of government can play five key roles very effectively, building a more capable public sector, if they follow four principles.

The Need for Action

A Strained Government Model

Government ministries such as transport, education, health, energy, defense, housing, and justice exist in nearly all countries. Ministerial boundaries are frequently adjusted, but unlike in the private sector, there are very few fundamental reorganizations.

Increasingly, the challenges that governments face do not fit neatly into this system. And the problem is getting worse, as disruptive events become more frequent and the public expects a faster and more coordinated response.

The resulting strain on this model of government is becoming clear. Ministries adopt conflicting policy positions, topics slip between the gaps, and central departments set up duplicative liaison teams in an attempt to strengthen their links with the ministries.

In BCG interviews with senior government officials, some common issues emerged, including the following.

- Lack of responsibility: “The center tends to issue orders but doesn’t deliver enough work itself.”

- Lack of knowledge: “The center doesn’t understand the policy, but tightly controls advice to the leader.”

- Complex processes: “It often fails to coordinate internally and creates duplicate work.”

- Staff attitude: “There’s a definite friction, where the center is perceived as better.”

- Lack of transparency: “Not many people have access to the prime minister, but many speak on the prime minister’s behalf.”

Such issues can add up to a center of all oversight and no action, issuing resource-intensive requests and reporting burdens without shouldering any of the responsibility, while simultaneously failing to use its position to act on issues escalated by the various departments or to lead a coordinated strategy. As a result, central teams are frequently established, operated only briefly, rescoped, and disbanded without achieving their vision.

Expansion Simply Adding to the Challenges

In the short term, it is not practical or necessary to radically reorient entire governments. But departmental leaders clearly need more support from the center, particularly in a crisis. Between 2013 and 2017, the 38-member Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that the staffing of government centers had increased significantly for most member governments. Covid-19 further accelerated this growth, with three in four centers providing coordination support for their government’s pandemic response; preliminary OECD data suggests this growth is continuing.

In the short term, it is not practical or necessary to radically reorient entire governments.

The scale of the increase varies among countries. In New Zealand the percentage of government employees in central ministries—of the prime minister, cabinet, and treasury, and the public service commission—increased only slightly between 2013 and 2022, according to the country’s public service commission. In the UK, in contrast, the Office for National Statistics reports that the number of government center employees (within 10 Downing Street and the Cabinet Office, including its agencies, and HM Treasury) grew threefold over the same period.

Such growth does not necessarily mean greater effectiveness, however. Expansion at the center can increase costs and hurt public outcomes—simply augmenting the challenges already faced.

Five Key Roles for the Center

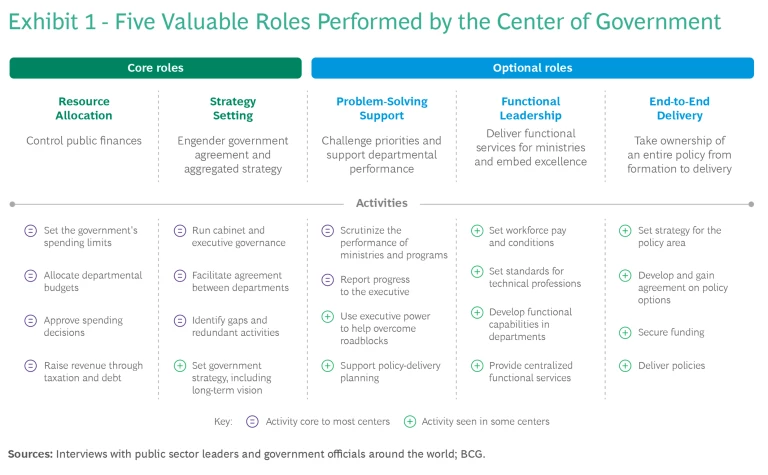

Centers today perform varied roles. The most common of these are resource allocation and strategy-setting. Indeed, these are core responsibilities of most centers of government. Three additional roles—problem-solving support, functional leadership, and end-to-end delivery—are often optional and may exist outside the center or not at all. (See Exhibit 1.)

We find the following five key roles in the center, in order of most to least frequently seen:

1. Resource Allocation. The center of government controls public finances through tax policy and borrowing, budget allocation, and spending management. This essential role is played by nearly all centers of government and cannot be performed elsewhere. It may also be combined with responsibility for economic policy. The center adds value in this area when it prioritizes the investments with the greatest public return, provides transparency and accountability for spending, and aligns spending across government departments with overall government strategy—a classic role of portfolio optimization.

2. Strategy Setting. The center drives cross-governmental agreement and delivers coordinated and longer-term strategies—a role that cannot be performed as effectively from anywhere else in the government. It adds value when it actively resolves disputes between ministries by understanding the fundamentals, envisioning the route to a resolution, and brokering a solution among the parties involved. It also adds value when it combines individual strategies into a single approach that is greater than the sum of the parts, informed by the longer-term vision of government. The center can also identify duplicative efforts among ministries, spot gaps in the actions being taken, and ensure that those gaps are filled.

3. Problem-Solving Support. In this role, the center challenges the ministries on their priorities and strengthens their ability to respond to issues as they arise. It adds value by, for example, using the power and influence of the leader of the executive branch to remove barriers in other areas of government. It can also draw on best practices across the government and the private sector to help with planning or use performance monitoring to gather insights, such as early warning signs of issues or problems.

4. Functional Leadership. The center can provide certain functions, such as HR, finance, procurement, and digital services, on behalf of government agencies or help develop technical excellence within the agencies themselves. It adds value in this area when it augments scarce capabilities in the agencies, unlocks economies of scale or skill, or creates cross-government standardization. It can support such efforts by building communities of topic experts that act as either centers of excellence, business partners, or owners of the function.

5. End-to-End Delivery. The center can take ownership of an entire policy area, from formation to delivery. This role adds value when issues are urgent and the center can remove layers of decision-making to get results quickly. The role may be permanent or may serve as an incubator before the center hands the responsibilities over to a ministry for the longer term. Finally, the center may provide a home for an issue that is so cross-cutting that there is no obvious ministry to take the lead and a joint-ownership model would be too fragmented.

A More Effective Center—Four Key Principles

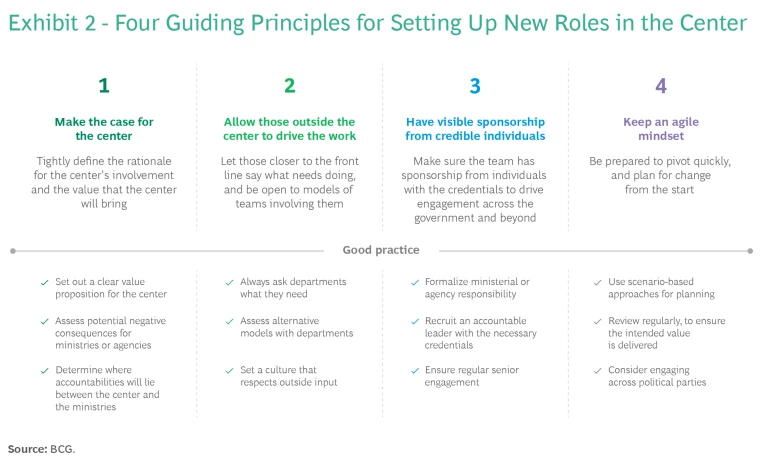

While the ways forward are not the same for every government, there are many examples of strong performance in the five key roles and of the power of an effective center. We distilled lessons from these—and from our experience advising private companies and central governments on how to strengthen public sector capabilities—into four principles for building a more effective center of government. These principles can be applied to each of the five roles. (See Exhibit 2.)

Make the case for the center. Teams at the center should set out a clear value proposition for the role they propose taking on. It should assess the potential consequences for ministries—both positive and negative—of the center’s involvement, and the capabilities that the center can bring to the ministries. In addition, teams should design accountability frameworks for the center and the various departments.

If the center cannot deliver the best results for the government and its citizens, then alternative options should be evaluated, such as cross-departmental committees or changes to ministerial responsibility. This may seem self-evident. However, it is common to find central teams whose purpose is unclear, that duplicate work, that offer more people but not unique tools or capabilities, and that have no real grip on the issues at hand because responsibilities are not explicit enough.

One successful example is Singapore’s Smart Nation and Digital Government Group (SNDGG), which helps plan strategic national projects from end to end and supports the vision of Singapore as a country seamlessly supported by technology. Established in 2017 within the prime minister’s office, it also has a functional leadership role in supporting government bodies in their digital transformation, such as building digital platforms centrally to be used for the ministries’ digital services, leveraging economies of scale through the merger of existing digital units. In fact, this type of digital support for the country’s ministries has been one of the keys to its success. In addition, given that the Smart Nation initiative is a priority of the prime minister, the resulting direct reporting line provides a strong mandate, helping the SNDGG to generate change.

If the center cannot deliver the best results for the government and its citizens, then alternative options should be evaluated.

Let those outside the center drive the work. Those close to the front line, in departments and independent government agencies, are typically the knowledge experts of their portfolio area and have direct experience turning strategy and policy into a reality for the public. As a result, they should have a say in what needs doing, and teams at the center should be open to models that involve them.

While the center’s primary function is to serve the leader of the executive government, setting direction and issuing instructions, the way the center exercises that power is important. Too often, we see individuals without the appropriate level of knowledge feeling obliged to steer ministries because the center is higher in the organizational hierarchy. Yet, we know that lack of delivery experience is already an issue in policymaking, and this distance from the front line just exacerbates it.

Based on our case experience, best-practice for this principle includes the following:

- Supporting a “one-government” culture that places high value on collaboration and respects the knowledge and experience each ministry or agency brings to the table

- Allowing ministries to shape requests for information from the center, ensuring that reports provide useful data for both the center and the ministry

- Considering whether alternative models for central teams are viable, such as joint units with ministries

- Actively asking ministries and those on the front line what they need from the center and embedding it into regular processes (e.g., reporting requests).

The United States’ Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) State Innovation Model initiative demonstrates the value of allowing frontline officials to drive the work and implementation of government programs. Established under the Affordable Care Act, the program aimed to improve the quality of patient care by encouraging state governments to use their own policy and regulatory tools to generate multi-payer health care delivery and payment reforms. The initiative awarded funding of nearly $950 million to 34 states and territories and the District of Columbia. The CMS funded the program but did not rigidly structure it—allowing the states themselves to accelerate their health care systems’ transformation, improve health care for CMS beneficiaries, and reduce the costs incurred.

In particular, the CMS initiative allowed delivery and payment structures to be adapted state-by-state for varying needs. Ten states, for example, implemented a patient-centered medical homes model, while five pursued episode-of-care models in which the provider receives a prospective payment for specific conditions. While the CMS played an important role in financing and policy coordination (providing the states with the necessary funds and some associated guardrails), the states implemented reforms that were devised under a comprehensive plan developed by the states themselves. This approach avoided the pitfalls of an overly prescriptive center-led program and prioritized input from those closest to the service needs.

Have visible sponsorship from credible individuals. Central teams, despite their best efforts, too often struggle to obtain quality engagement from outside the center. Frequently this is because appropriate sponsorship at political and governmental levels is not in place.

To persuade ministries and other agencies to prioritize the center’s input, officials in the center need a clear mandate from the leader of the executive branch or a credible authority figure in a leadership role willing to put their name on the line. This figure should have the credentials to bolster engagement across the government and beyond.

Gaining this type of sponsorship for all the center’s roles may be unrealistic. If a sufficient level of sponsorship cannot be found, then it is probably not worth the center (or anyone else) playing such a role.

The UK’s Covid-19 Vaccine Task Force has demonstrated how putting this principle into practice can contribute to success. The Task Force was established in April 2020 with the end-to-end role of procuring the Covid-19 vaccine for the UK. It faced enormous challenges, given that the UK had less buying power than larger regions, such as the US, the EU, or China. Nonetheless, by December 2020, the UK was the first western country to begin vaccinations, and suppliers had agreements in place for 357 million doses.

Sponsorship from credible individuals helped achieve this result in three ways.

- The government’s chief medical adviser recognized that the government had few skills in the development or procurement of new vaccines and sought the prime minister’s approval to set up a specialist unit led by industry experts. To lead the Task Force the government then appointed Dame Kate Bingham, a venture capitalist with 26 years of experience in life sciences—and entirely new to government. This move resulted in a fundamentally different approach to the task, as well as close work with vaccine manufacturers, allowing the government to place early, big bets on a broad portfolio of unproven vaccine producers and draw them to the UK.

- Dame Bingham reported directly to the prime minister. She also established an investment committee of ministers, similar to a venture capital firm, that was able to approve spending decisions rapidly.

- The government created a Covid Vaccine Deployment ministerial position and gave it to Nadhim Zahawi of the Department for Business. He was freed of his earlier responsibilities and therefore had absolute clarity of mission.

Keep an agile mindset. The center should monitor its own activities for relevance and be prepared to pivot quickly, planning for change from the start of any initiative. Central activities often continue when they no longer have a clear purpose and only place a burden on ministries, such as when the center continues to ask for reports that are no longer used. One reason is that the center is more exposed than other government bodies to the impact of changing government priorities and political cycles.

The center should monitor its own activities for relevance and be prepared to pivot quickly, planning for change from the start of any initiative.

Best practices for creating and sustaining an agile mindset include the following:

- Holding regular activity reviews to assess if the central team is still meeting its objectives and not duplicating others’ work, and adapting—or even shutting down the initiative

- Working incrementally to deliver measurable results for citizens within the current political cycle, ensuring a return on investment even if the policy direction changes

- Using scenario planning from day one to identify risks that could cause sponsorship to be lost or could change the need for the given role, and planning what the team would do if these risks materialized

- Engaging with the political opposition early to understand the likely impact on the center of changing priorities or cycles.

One Australian state government’s approach illustrates the way longer-term projects can be set up for success. The government wanted to establish a ten-year workforce development strategy for schools, which up to that point had been constrained by locally run school systems and a limited culture of professional development and performance management. By its nature, the topic was also politically sensitive; it therefore required a long-term approach that pursued the greatest public outcomes. Given this, any strategy would need to be protected against the political cycle.

The civil service accomplished this by ascertaining the risks and building in mitigations from day one. For example, it gained the minister’s support to engage the shadow ministerial team—the opposing political party—and share the plans as they evolved, treating the shadow minister as a senior stakeholder of the strategy. In this way, it protected an issue of critical importance to the state by ensuring that it could be continued if administrations changed.

Looking to the Future

As more and more cross-ministry issues arise, approaches confined to traditional departmental lines will no longer be enough. While radical government reorganization may be in the future, we have not in recent years seen it play out in a practical way. As a result, the center will remain a key resource for departments and agencies throughout the government. By following the principles set out above, governments can ensure that the center is more effective, agile, and collaborative—and biased toward action rather than oversight.