This article is part of a series examining the competitive outlook for key global process industries and how they can prosper in an uncertain future.

Against a backdrop of slowing demand, high energy costs, and looming regulatory and technological disruptions, the petrochemical industry is poised for significant change. Players will have to adapt to the sector’s evolving dynamics or risk damaging their competitiveness. How they respond to the challenge will determine whether they are future winners or losers. (See “The Future of Process Industries.”)

The Future of Process Industries

Each article in the series will examine the nature of the new business reality faced by a particular process industry and how the coming changes will drive technological progress, redefine the industry’s cost structure, and reshape its competitive landscape. The goal: to provide industry leaders with the data and guidance needed to ensure that their companies can thrive in the coming years.

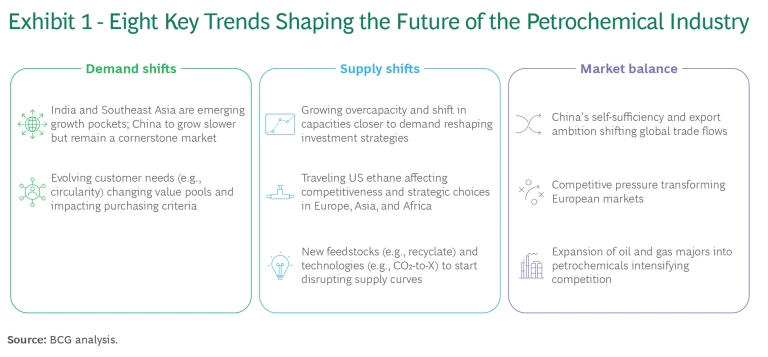

In this article, we examine eight trends that will shape the future of the petrochemical industry over the next ten years. (See Exhibit 1.)

Slowing—and More Complicated—Demand

After the volatility of the COVID-19 era, petrochemicals demand growth is set to weaken over the next ten years, driven by a decelerating global economy and the shift in economic activity toward less materials-intensive sectors. Global GDP is expected to rise by a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of about 2.4% from now through 2035, down from approximately 2.7% from 2014 through 2024. Global petrochemicals demand is projected to grow by around 3% through 2035, compared with 3.3% from 2014 through 2024.

The biggest driver of the coming slowdown is China, where an aging and shrinking population as well as efforts to rebalance the economy toward services and high tech are creating a weaker demand outlook for the domestic petrochemicals sector.

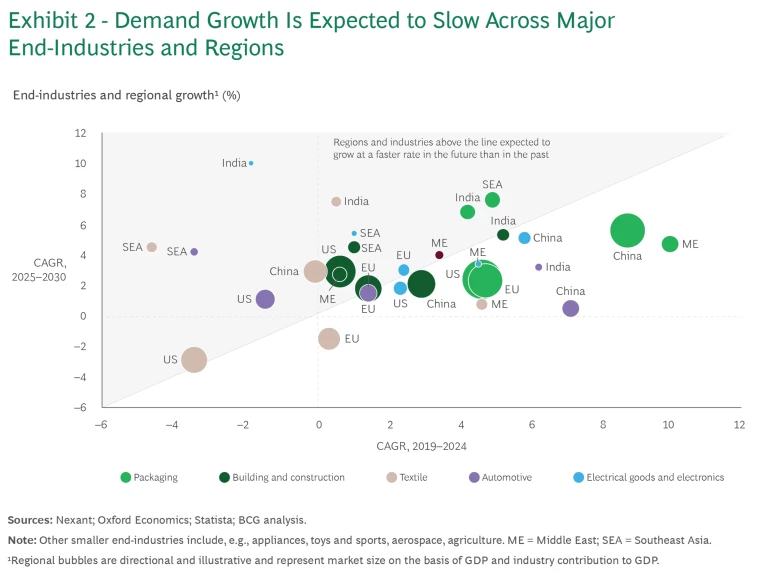

Exhibit 2 shows the scope and de-averaged nature of the worldwide economic slowdown, with more than 70% of global GDP expected to grow more slowly in the next five years than over the past five. But the data also shows that growth in several countries will continue to accelerate. India’s economy, for example, is set to expand by a CAGR of 5% to 7% through 2035.

At this rate, India will become the world’s third-largest economy by 2030. Rising household incomes will drive India’s economic growth, while demand for chemicals and petrochemicals will increase at roughly the same rate as the economy. Strong growth in textiles, packaging, and electrical goods and electronics, as well as the shift of some chemicals-intensive manufacturing into India and out of China to reduce geopolitical risk, will also contribute to demand.

For many petrochemical players, the question they need to answer about the markets of India and Southeast Asia is no longer whether to enter but how. This includes reevaluating their go-to-market strategy and channel options—deciding if they will operate as a pure importer or, if they opt to build a local presence, assessing options for accessing local capacity, feedstock, and pools of demand.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on industrial goods

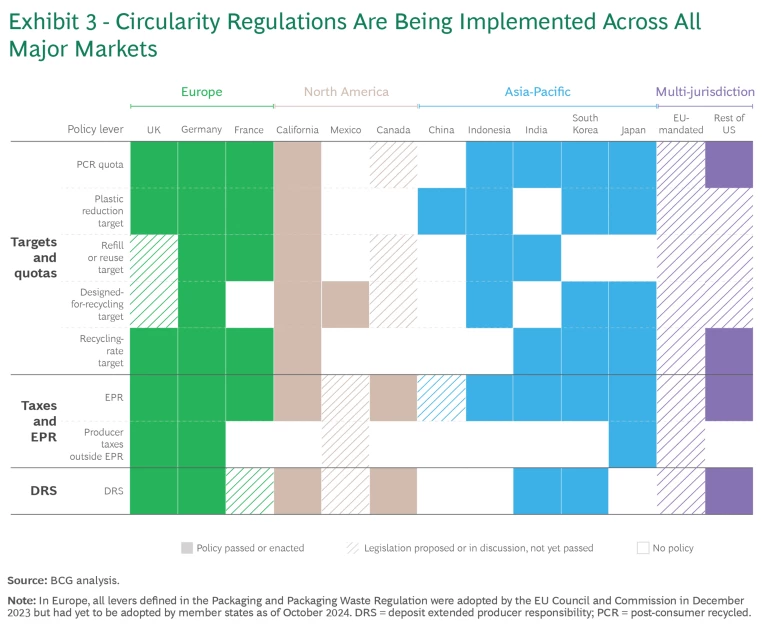

At the same time, customer needs worldwide continue to change rapidly, owing to the impact of regulations and new end-user and consumer preferences. This is especially true of more sustainable materials, including low-carbon and circular ones, where regulations are already changing the field of play. (See Exhibit 3.) For example, several industry estimates suggest that up to 50% of global polyethylene (PE) demand in 2040 could be for low-carbon, circular, and bio-based grades.

Circularity—the Uncertain Imperative

Perhaps no topic in petrochemicals is as potentially disruptive, or carries as much uncertainty, as circularity. While some consumer goods companies have announced that they are scaling back ambitions for recycled packaging, the EU has passed the Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation. This introduces sweeping new requirements related to recyclability, recycled content, and biodegradability. In addition, the US has signaled its support for caps on virgin polymer production in the ongoing Global Plastics Treaty negotiations, a potentially massive development.

Plenty of variables remain hard to predict globally: whether the negotiations will result in regulations and implementation timelines, whether definitions of “recycling” and “recycled content” can be agreed on that will meet the bar for regulators, what kinds of consumer value propositions the new circular materials will provide, and, above all, what willingness to pay will look like in the long run.

Still, the direction of travel is clear. Despite substantial regional differences, current plastic waste recycling rates are low, at around 10% globally. But with the right investments in collection and sorting infrastructure, those figures could change fast. In our most ambitious scenario, recycling rates for polyethylene terephthalate (PET) could rise from a worldwide average of 10% to 15% today to 35% to 40% over 2035–2040 (inclusive of depolymerization), while the rate for polystyrene (PS), which is less than 3% today, could increase to 15% to 20%. As a result, demand for monoethylene glycol (MEG), a key precursor for PET, could shrink globally under this scenario.

There are several reasons that recycling rates are not higher: municipal waste and recycling infrastructure, consumer behaviors, policy (such as deposit schemes), brand owner packaging design, as well as the capability of mechanical and advanced recycling technologies. These factors also put a reasonable upper bound on future projections. All will need to develop in tandem to materially improve recycling rates.

Achieving our ambitious scenario will require petrochemical companies to make substantial investments, not only in recycling technologies that enable low-cost conversion at scale but also in upstream partnerships that allow less expensive, widespread collection and sorting to meet the demand for waste feedstock.

Petrochemical players are already making these partnerships up and down the value chain. For example, SABIC has partnered with Mars and Landbell Group to create a closed-loop recycling project that uses certified circular polypropylene (PP) derived from mixed-use plastic waste. Meanwhile, Dow Chemical’s recent acquisition of Circulus, which provides high-quality post-consumer recycled (PCR) resin for film applications, is a vote of confidence in mechanical recycling.

Circularity trends also offer a rich opportunity for value-creating innovation. Companies are looking to use technologically advanced materials to enhance functionality (by creating stronger barriers to moisture and oxygen, for example, for a longer shelf life and improved safety) and develop lighter packaging products to help curb emissions. Similarly, automotive players are focusing on recyclable components to reduce waste from end-of-life vehicles.

Gone are the days of petrochemicals being monolithic commodities. The emerging environment is placing fresh demands on petrochemical companies’ commercial capabilities.

All these developments will require new capabilities to identify the best customers, sell new value propositions, and price appropriately according to customer willingness to pay. Gone are the days of petrochemicals being monolithic commodities. The emerging environment is placing fresh demands on petrochemical companies’ commercial capabilities. BCG and the World Economic Forum’s recent green go-to-market roadmap for commercializing sustainability in several energy-intensive industries, including chemicals and petrochemicals, highlights a few key commercial imperatives.

A Changing Supply Picture—New Feedstock Sources and Technology Disruptions

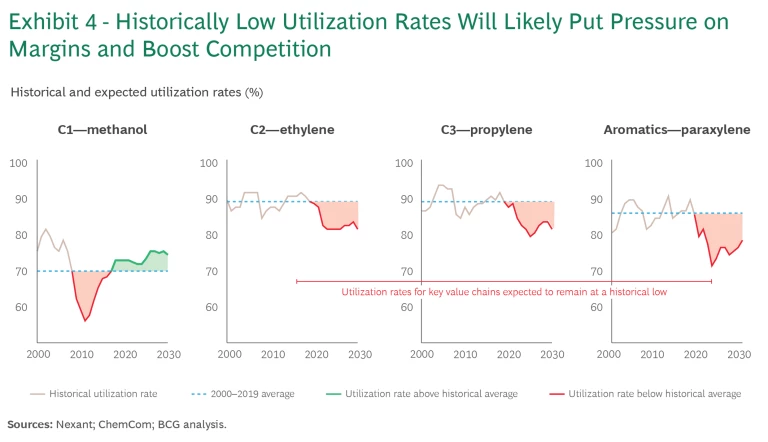

Although global capacity additions will be slower than before, we still expect the growth in supply to outpace that in demand. The resulting overcapacity will push utilization rates for petrochemicals factories below historical averages across most key chemical value chains. (See Exhibit 4.)

Here too, there are important regional differences. China’s push for self-sufficiency is impacting global trade flows, while developments in North America and the Middle East are tempering the pace of new additions in those regions. (See “Regional Capacity Trends Will Shape Players’ Investment Strategies.”)

Regional Capacity Trends Will Shape Players’ Investment Strategies

- China will continue to add new capacity to achieve self-sufficiency in petrochemicals but at a slower pace (increasing capacity by less than 4% annually over the next five years compared with about 9% during the past five years). The country has even started exporting selected products, partly to ensure that its factories are busy. But because of the age, small scale, and technological obsolescence of some plants, as well as environmental regulations that collectively result in economic pressure, we also expect China to contribute to rebalancing global petrochemical supply and demand.

- In the Middle East, capacity additions slowed in the 2020s. Some greenfield and brownfield investments are still underway, though less than in the past. Companies instead are increasingly looking at M&A opportunities in chemicals and petrochemicals, particularly if these deals help secure crude placement abroad or provide market access for their products.

- India looks set to follow China’s path toward self-sufficiency in petrochemicals. Because it lacks feedstock advantages, however, India is securing feedstock through partnerships and joint ventures with lower-cost oil and gas players. For example, Haldia Petrochemicals recently signed a ten-year naphtha supply agreement with QatarEnergy.

- Investments in new petrochemicals projects in Southeast Asia—particularly in Indonesia and Thailand—will continue, driven by rising local consumption.

- In North America, capacity additions will decelerate as the boom in US shale gas, an important source of inexpensive feedstock, slows. There will still be some investments, however, mainly in new ethylene crackers.

- In Europe, we expect some rationalization of production assets and new value chain configurations owing to higher feedstock and energy costs compared with other regions. These factors have already caused players to close uncompetitive production assets. Reductions of more than 4% of the current Western European ethylene capacity have already been announced. Several hundred more kilotons will be required to get to reasonable economic operating rates of approximately 80% and even more to ensure a healthy industry. Nevertheless, some companies, such as the UK’s Ineos, are looking for opportunities to expand in Europe by building new production capacity. Such European investments will likely focus on coastal areas (to ensure access to less expensive feedstock imports) and integrated assets (to balance margin risks in any single part of the business).

In the US, as the pace of investment in new domestic petrochemical capacity slows along with the shale boom, we are starting to see feedstock and olefin exports emerge as a new industry dynamic. Inexpensive traveling US ethane is reducing costs for players in Europe, Asia, and Africa, enabling them to fill downstream plants domestically while remaining competitive. For example, Ineos is importing US ethane feedstock using state-of-the-art vessels, providing a cost-effective and reliable supply for its European plants—and other companies are following suit. Demand for exported US ethane increased by 50% from 2019 through 2022 and is set to rise further.

A new, potentially more disruptive source of inexpensive feedstock—namely, trash—could change the game yet again over the longer term. Wide variations in the availability and cost of plastic waste exist worldwide. As circularity becomes more important to overall petrochemical supply production, however, access to inexpensive, high-quality waste will become a new source of advantage.

Other sources of technological disruption include crude-oil-to-chemicals (COTC) technology, which bypasses conventional refining and converts crude directly into petrochemicals. This technology is increasingly being used in China for paraxylene production. COTC makes Chinese production costs far more competitive and will support China’s efforts to become self-sufficient in select petrochemicals. It is already causing some South Korean paraxylene exporters to China, among others, to search for new demand hubs and consider capacity rationalization.

E-technologies (which use electricity from renewable sources to reduce CO2 process emissions), CO2-to-X (carbon transformation), and other circular tech solutions are also expected to disrupt petrochemical supply curves and trade flows. Major chemical and petrochemical players are actively exploring these technologies, and several have established pilot projects. For example, BASF, Linde, and SABIC have created a large-scale e-cracker demonstration plant at BASF’s site in Ludwigshafen, Germany.

Impacts on Market Balance

Slowing demand, overcapacity, and greater competition will be significant features of the petrochemical industry over the next ten years. According to our calculations, returning utilization rates to historical averages requires the removal of 20 mtpa to 45 mtpa of production capacity across key building blocks—particularly ethylene, propylene, and paraxylene—primarily in China and Europe but also in Northeast Asia. Here are some of the major forces that we expect to impact the balance of supply and demand in the global petrochemicals market during the next decade.

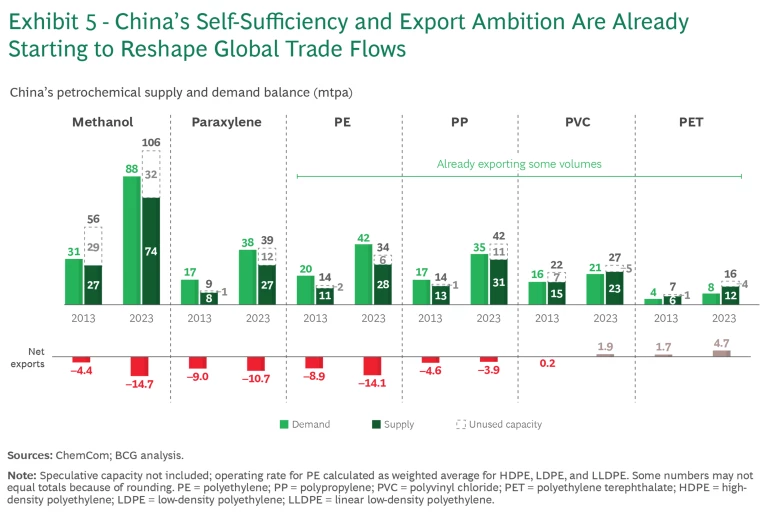

China. Despite a middling position in the global supply curve for most petrochemical products, the country has already achieved technical self-sufficiency in several key products, including methanol, paraxylene, PP, MEG, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and PET. Furthermore, China’s export ambition in PP looks set to increase, adding to established exports in PVC and PET. (See Exhibit 5.)

Europe. The broader European chemical industry is confronted by a number of factors that could affect companies’ international competitiveness, including stagnating demand, the ongoing energy crisis, overdependence on a handful of suppliers, and an ambitious climate regulation agenda (such as domestic carbon pricing, including the Emissions Trading System; and cross-border carbon pricing, such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism). These dynamics are creating either challenges or opportunities depending on the value chains and products.

To overcome these hurdles, European companies are attempting to transform their businesses by finding new ways to boost their competitiveness and establishing green markets in cooperation with policymakers and end-customers.

Leading European players are forging or considering new partnerships with “cracker+1” companies (which normally build and operate a new plant in collaboration with another player) in the Middle East and North America, importing feedstock and key intermediates from outside the region, implementing partial value chain disintegration or global integration opportunities, and applying fixed cost reduction programs.

For European petrochemical producers, green investments have changed from a growth opportunity to a strategic necessity owing to the European Union’s ambitious emission reduction targets.

Even exporters to Europe need to prepare for a challenging commercial environment. Many Middle Eastern players are getting ready for tougher sustainability requirements from European customers and implementing decarbonization programs to reduce the impact of the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

Oil and Gas Majors’ Expansion into Petrochemicals. As demand for fuels declines, oil and gas players are actively exploring different growth strategies, including investing in petrochemicals and COTC.

The very high capital requirements of these projects will create barriers to entry, favoring oil and gas companies with strong balance sheets but significantly disrupting smaller, localized, and pure-play petrochemical players.

What It Will Take to Win—Six Implications for Leaders

The next 10 to 20 years in petrochemicals will not look like the past 10 years, or even the past 5. Here are six key imperatives to become the petrochemical winners of tomorrow.

- Seize new growth opportunities. As new demand hubs in India and Southeast Asia become more established, petrochemical companies should expand their access to priority customer segments and channels, through initiatives such as strategic partnerships and joint ventures.

- Develop a robust China strategy. As the Chinese market becomes self-sufficient and more competitive, bulk exports to China will not work. Players need to upgrade their approach to China—by finding the value-creating bets that can still succeed in the world’s largest market or developing a Plan B (including staving off the risk of competition from Chinese exports).

- Rethink your European market positioning. European producers should explore new ways to increase their cost competitiveness and proactively develop green markets with policymakers and end-customers. Meanwhile, key exporters to the region should identify their future competitive advantages under different regulatory scenarios.

- Ensure that your talent and capabilities are future-ready. All process industries, including petrochemicals, are facing a talent trap. They are struggling to recruit younger employees as waves of older workers with deep institutional knowledge are retiring. To navigate these changes, players should focus on improving their value proposition for younger talent and retaining knowledge, leveraging new tools (like generative AI) to capture old wisdom.

- Reinvigorate your sales and marketing muscle and approach. To navigate intensified competition, growing product complexity, and the effects of experienced workers retiring, prioritize the strengthening of foundational sales skills and tactics—combining the best practices of the past with the new knowledge, tools, and needs of future customers.

- Forge creative partnerships across the value chain. To accelerate progress and time to market in emerging value pools, strategically evaluate and secure opportunities through partnerships (including technology investment and development), especially in recycling and circularity. These can be with customers, with technology leaders, or to secure access to new feedstock.

In dynamic times like these, the only certainty is uncertainty. Players should aim to build an advantage for themselves out of this reality by leveraging scenario-based thinking related to key sources of uncertainty and by developing big plans to match the big changes that are on the horizon.

The authors thank Marcus Morawietz, Clint Follette, Susumu Hattori, Marcin Jędrzejewski, Arun Rajamani, Jingshi Hu, Jinyoung Baek, Amit Gandhi, and Veronica Muzoka for their expertise and support in the development of this article.