Our Inclusive Advantage Consulting Services

Related Services

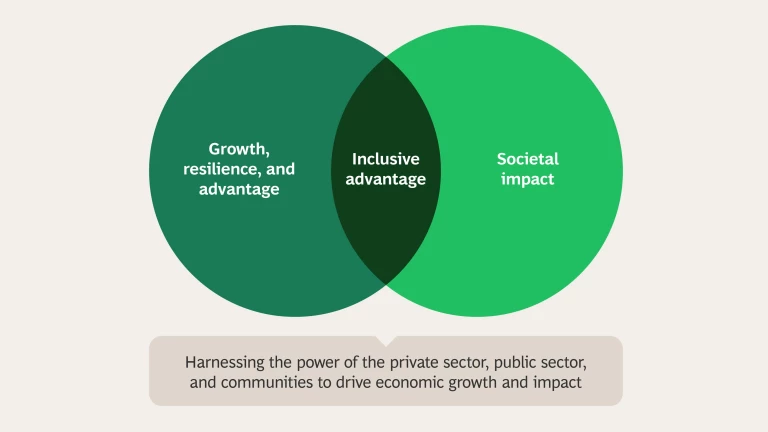

Our Approach to Inclusive Advantage

Many organizations face a world of talent shortage -- building more inclusive organizations -- which benefit all employees -- is often crucial to building a stable, superior workforce. With the diversity in many societies increasing, the opportunity to find new markets in serving the underserved. BCG helps organizations rethink and broaden their strategy to create lasting advantage, profitable solutions and societal impact.

- Build fair and inclusive supply chains via diverse supplier programs, supplier engagement and human/labor rights tools

- Personalizing the employee value proposition for frontline workforces to improve talent access and productivity in a way that better serves individual needs

- Reach new customers, open new markets, innovate business models to drive growth while addressing market inefficiencies and underserved segments in key sectors

Our Client Work in Inclusive Advantage

The Center for Inclusive Advantage

Meet Our Inclusive Advantage Consulting Leaders

Our Insights on Inclusive Advantage