This article is an excerpt from Global Leaders, Challengers, and Champions: The Engines of Emerging Markets (BCG report, June 2016).

2016 BCG Global Challengers

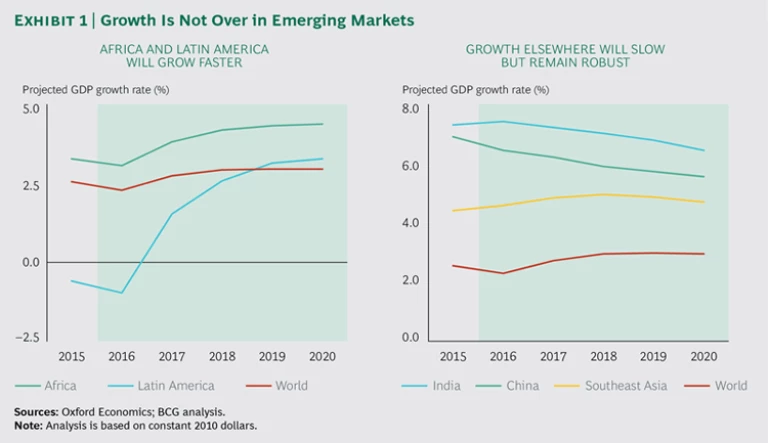

Slowing economies, rising geopolitical risks, and falling commodity prices are real problems, but they do not need to be show stoppers for the global challengers and other aspiring companies in emerging markets. Most of these markets are still growing faster than their mature counterparts. (See Exhibit 1.) Their demographic and consumer spending trends are also more favorable than those of mature markets.

Consider the following:

- Between 2015 and 2030, the population of emerging markets is set to expand by 17%, more than three times faster than the rate in mature markets.

- Between 2015 and 2030, the urban population of sub-Saharan Africa will expand by 70%, double the still impressive rate of the Asia-Pacific region, and more than three times the rate of Latin America.

- Even if GDP growth slows to 5.5%, China and India will add $3.9 trillion in consumption over the next five years, equal to the entire GDP of Germany.

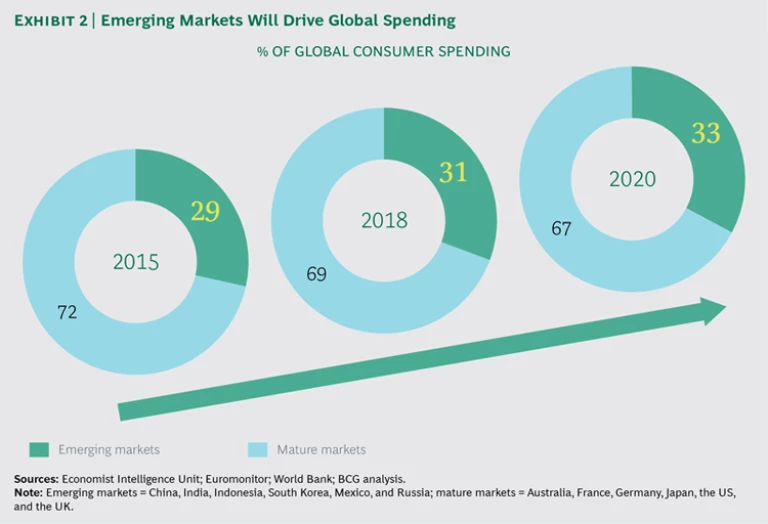

- Emerging markets will account for one-third of global consumption by 2020, up from 29% in 2015. (See Exhibit 2.)

It’s a more challenging environment than it was five years ago. But for companies that want to send themselves into global orbit, emerging markets are still strong launching pads, albeit ones that are becoming more crowded.

The New Champions

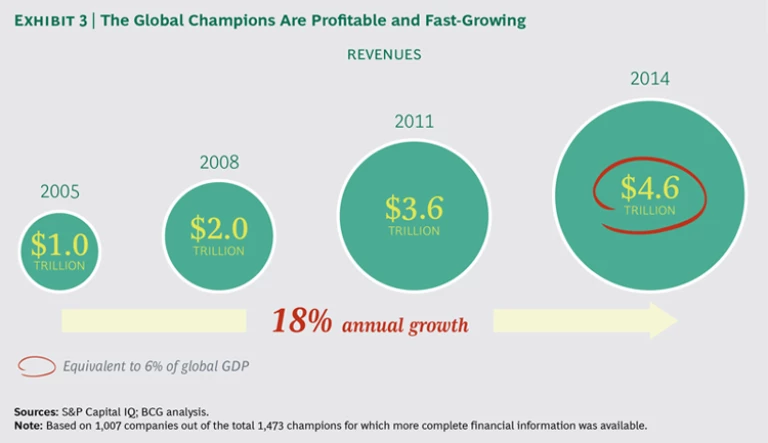

As global challengers look to grow in a slower-growth world, they will face increasing competition not just from multinationals—their historic adversaries—but also from homegrown rivals. We have identified nearly 1,500 companies based in emerging markets that, while not qualifying as global challengers, are still successful, growing companies.

These companies—the champions—tend to be smaller than the challengers but

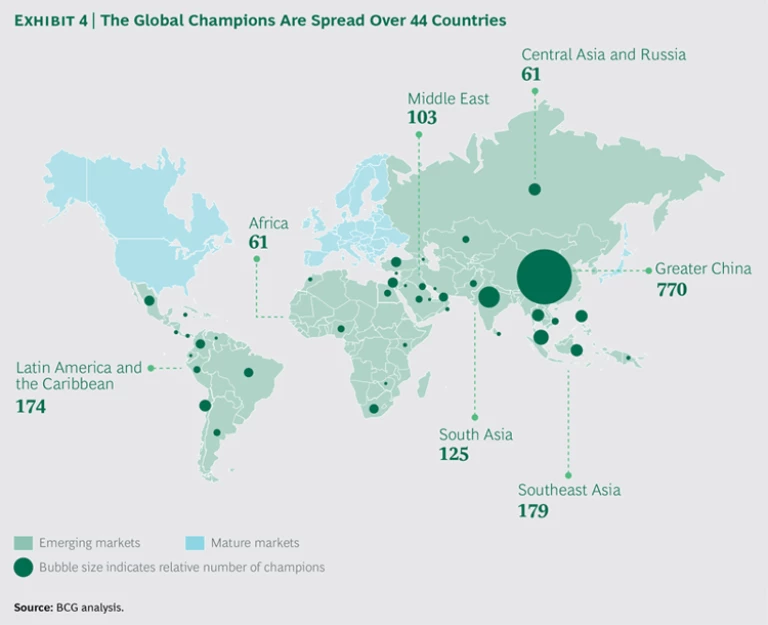

Champions are companies to watch over the next ten years. Like the global challengers, they are concentrated in China and India. But African, Latin American, and Southeast Asian companies are also well represented. (See Exhibit 4.)

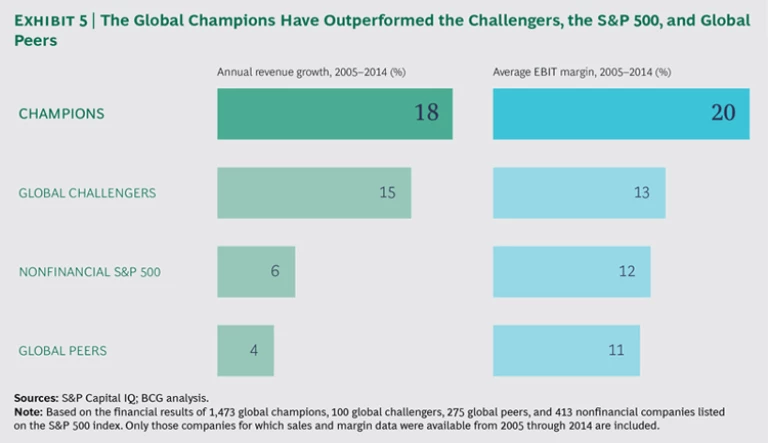

The champions have grown faster than the global challengers over the past five years and are more profitable. (See Exhibit 5.)

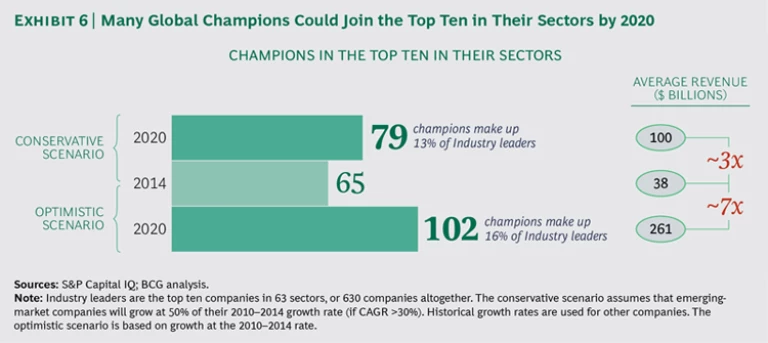

Given their current growth rates, many champions are likely to become top-ten companies in their industrial sector by 2020. (See Exhibit 6.)

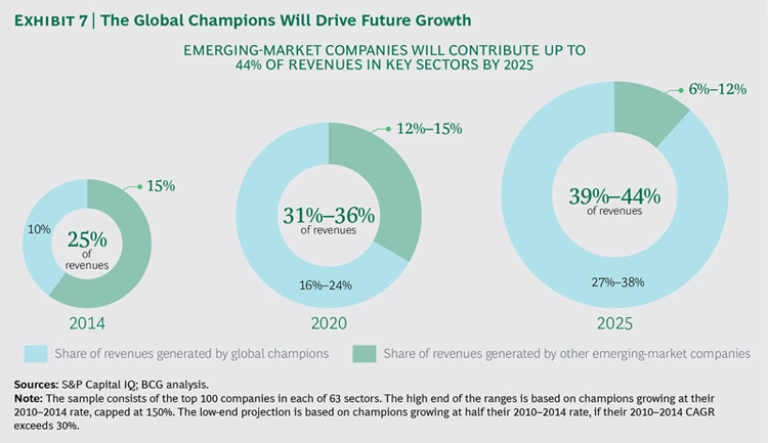

These companies will also be responsible for most of the world’s economic growth through 2025. (See Exhibit 7.)

In other words, within five years, the top-ten lists of many industrial sectors will be populated by several companies that are virtually unknown today outside their home market. Here are just three examples of champions that demonstrate their dynamism:

- Aurobindo is one of India’s five largest pharmaceutical companies, measured by both sales and market capitalization. It has grown by 18% annually over the past five years, reaching $1.9 billion in sales in fiscal year 2015, and the US Food and Drug Administration has certified more than 230 of its drugs.

- Shenzhen O-film Technology is the largest producer of touchscreens in the world, with 2014 revenues of $3.1 billion. Its annual revenue growth has more than doubled over the past five years. This Chinese company has created five R&D centers around the world and secured more than 1,100 patents. It has invested more than 4% of revenues in R&D since 2011 and used M&A to acquire key technologies. To diversify away from the slowing smartphone market, Shenzhen O-film Technology has invested in smart car, fingerprint sensor, and camera technologies.

- Alsea, of Mexico, is the largest restaurant operator in Latin America, running quick-serve and casual-dining franchises such as Starbucks, Burger King, Domino’s Pizza, and The Cheesecake Factory. It has created economies of scale across these brands by building several distribution centers and relying heavily on shared services. Alsea also has a presence in Spain. Revenues have been growing by more than 25% annually in recent years.

Facing the Future

Against a backdrop of slower growth and greater competition, global challengers, local dynamos, and champions alike will need to do more than float higher on the tide of an expanding economy. They will need to compete.

This will be tougher for some challengers than for others. Many state-owned enterprises, such as shipping and port giant COSCO, are facing pressure to restructure. Family-owned companies, especially newer ones, will likely need to transition to a new generation of leaders. The average age of CEOs at family-owned businesses in Asia is 61, so this is a real and present concern. Conglomerates in particular will need to focus on productivity and profitability, not just top-line growth.

Companies from emerging markets increasingly will need to rely on strategic M&A to build their capabilities and reach their goals. Tech Mahindra, an Indian IT services company, has thoughtfully expanded its business through deals. In 2015, Tech Mahindra and a sister company bought Italian design house Pininfarina to expand their high-end capabilities. That same year, Tech Mahindra also bought Geneva-based Sofgen Holdings, to move into the banking industry, and Lightbridge Communications, to expand its network-services capabilities.

Not all global challengers will be up to these tasks. But if their past is any indication, most of them will continue to be viable companies, and many will become global leaders. In the ten years that we have been tracking them, global challengers have grown even faster and stronger than we initially expected.