As concerns increase about the onset of a global recession, M&A dealmakers should take heart: a recent BCG study finds that acquirers generally see higher returns from deals made in a weak economy. The findings are discussed in the related article from the 2019 M&A report, “Dealmakers Do Well in Downturns.”

But how should dealmakers capitalize on the opportunities? Drawing on our analyses and experience, we have identified three imperatives for mastering M&A in a downturn:

- Apply the lessons of experience.

- Aggressively pursue downturn M&A opportunities.

- Use transformational deals to stay ahead of the curve.

The 2019 M&A Report

The 2019 M&A Report

- Downturns Are a Better Time for Deal Hunting

- Dealmakers Do Well in Downturns

- How to Master M&A in a Downturn

Apply the Lessons of Experience

Experienced buyers are prepared to succeed, well-versed in how to use M&A to further their strategic objectives, and realistic about the potential to create value.

Preparation. It goes without saying that preparation is essential for success in downturn M&A. But many companies are not ready to take advantage of the opportunities.

Before the downturn actually occurs, be financially and strategically prepared for M&A. This means thinking about sources of funding and building up a “war chest” to tap into for acquisitions. It also means having an ongoing discussion about, and developing a list of, potential targets that suit your strategic requirements. Developing a target list before the downturn is a no-regrets move. If the economy remains strong, the company can act quickly if a buying opportunity (such as a PE exit) arises. And if the economy weakens, targets may be available at bargain prices.

As discussed earlier, dealmaking tends to take longer in a downturn, owing to factors internal and external to the company. To prevent unnecessary delays, it is crucial to have well-structured internal decision processes and strong M&A capabilities. Ensure that you can act fast and in a structured manner if and when a suitable target becomes available. Perform the necessary level of due diligence and be mindful of process hurdles, such as shareholder approval.

Proficiency. Experienced acquirers outperform occasional dealmakers. This holds especially true for weak-economy deals within the same industry.

During an economic downturn, two commonly executed M&A strategies involve acquisitions within the buyer’s industry: consolidation (acquiring one or a few comparably large direct competitors to reduce overcapacity and/or competitive pressure) and roll-ups (acquiring several relatively small direct competitors to gain scale and scope advantages in a fragmented market). The need to relieve cost pressure in a weak economy makes the benefits of such core deals especially attractive. Prominent examples include J.P. Morgan’s takeover of Bear Stearns and Westpac’s acquisition of St. George Bank during the 2008 financial crisis. The consolidation of the steel industry during the years after the financial crisis also exemplifies this strategy.

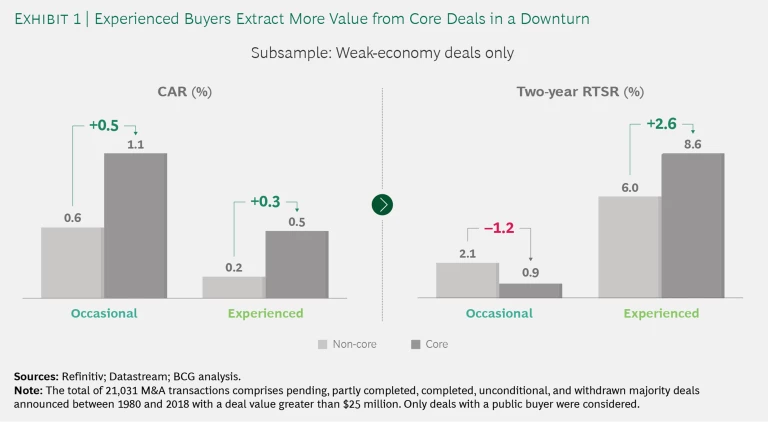

Although the strategic concept is sound, occasional buyers often fail to create much value from such core deals. (See Exhibit 1.) In a weak economy, investors initially favor core deals. For occasional buyers, the CAR around the announcement date of core deals exceeds that of noncore deals by 0.5 percentage points, while for experienced buyers the CAR differential is 0.3 percentage points. In analyzing value creation after two years, however, it appears that occasional buyers fail to meet investors’ expectations. For occasional buyers, the two-year RTSR of core deals is 1.2 percentage points lower than that of noncore deals. But for experienced buyers, the RTSR of core deals is 2.6 percentage points higher than that of noncore deals.

How do experienced buyers achieve superior value creation in core deals, including roll-ups and consolidations? Important skills include the ability to conduct a thorough and accurate assessment of the importance of additional scale and scope in the industry, the synergy potential, and the associated risk. For example, can large-scale mergers or acquisitions, which are usually complex, succeed in creating value through additional economies of scale? This benefit may not be realized if marginal production costs are already low or if the industry is better served through a collaborative, flexible ecosystem. Experienced buyers are able to anticipate the problems that could impede integration (such as significantly different corporate cultures), as well as the regulatory issues that could impact value creation or even lead to the deal’s failure.

Realism. Experienced acquirers are realistic. They do not assume that buying an appealing asset at a low price guarantees value creation. Sustainable value creation requires advanced dealmaking capabilities—even more so in a downturn. Assess a deal’s value creation potential realistically, and don’t overstate the potential for synergies or a performance turnaround. To maximize value extraction, be sure to integrate the target rigorously and rapidly.

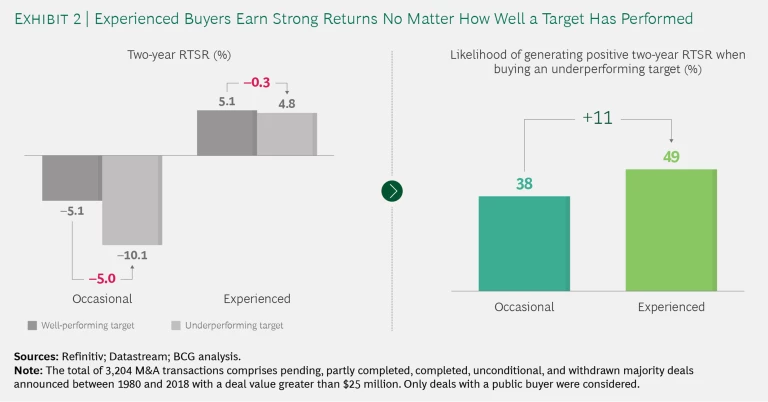

Companies that have superior operational capabilities are better equipped to withstand cost pressure in a downturn. Best-in-class companies have an advantage in M&A as well, because they can apply their capabilities to create tremendous value at poorly performing targets. But does M&A experience make a difference? To investigate, we used EBITDA margin as a proxy for a company’s performance relative to its industry. (We excluded the financial, insurance, and real estate industries from the analysis.) We found that, during a downturn, occasional buyers create less value when they acquire an underperforming target than when they acquire well-performing targets. (See Exhibit 2.) For experienced acquirers, however, the difference between acquisitions of underperforming targets and acquisitions of well-performing targets is insignificant—they earn strong returns regardless of how well the target performed. These findings also hold true when we adjust the returns for associated risk, as measured by the standard deviation of the two-year RTSR. Clearly, experienced buyers possess capabilities that allow them to extract greater value from underperforming targets.

Our research also shows that experienced buyers perform significantly better, on average, than occasional dealmakers when acquiring an underperforming target. Even so, experienced buyers create value only in about half of their downturn acquisitions. The fact that a deal has, at best, a 50% likelihood of success reinforces the importance of assessing the potential for value creation. But for companies that get it right, the rewards are tremendous. For example, after Sanofi acquired Genzyme during the downturn in 2009, the drug maker quickly revamped manufacturing processes and operations while pursuing synergies in the sales organization. In the automotive industry, after Groupe PSA acquired Opel, it applied its superior operational capabilities to transform the target company. Groupe PSA, the parent company of several automotive brands, had launched a highly successful turnaround program of its own in 2014. Applying its experience, Group PSA succeeded in reducing Opel’s operating costs and streamlining its production processes, among other improvements.

Boldly Pursue Downturn M&A Opportunities

Some companies may be inclined to ride out a downturn without pursuing M&A. But our research shows that a difficult economic environment should not, by itself, send dealmakers to the sidelines—especially if they have a strong and well-considered acquisition strategy. Indeed, downturns are, on average, good times to make deals. Our research also shows that having a bold corporate leader is an important success factor in carrying out difficult acquisitions and turning around a target’s performance.

Successful corporate leaders use dealmaking to shape, remodel, or even completely transform their corporate portfolio. A downturn may not be a good time to divest business units that are sub-scale or both sub-scale and noncore. Instead, it could be a good time to acquire complementary businesses that would allow a company to increase the scale or, in some cases, the scope of such business units. Increasing scale could set the stage for a subsequent divestiture or spinoff. A company can take advantage of the downturn to become a master of the corporate portfolio, as discussed in our The 2016 M&A Report.

Downturns often present good opportunities to increase the scale of business units, because suitable targets can be acquired at attractive valuations. The buyer’s business unit benefits from increased scale and potential cost synergies. In some cases, when the economy recovers, the buyer may find that the expanded business unit can operate on a standalone basis. To reap further benefits from the newly gained clarity into the corporate portfolio, the company could split itself into two or more at-scale, pure-play businesses.

For example, in 2009, taking advantage of depressed prices in the aftermath of the financial crisis, Kraft acquired Cadbury following a hostile takeover bid. Kraft’s goal in acquiring Cadbury was to increase the scale of its snacks business, especially in emerging markets. Cadbury rejected the initial offer, arguing that its absorption into a slow-growth conglomerate dominated by Kraft’s North America-focused groceries business could limit the growth potential of Cadbury’s snacks business. Kraft responded by increasing its offer price, and Cadbury’s shareholders ultimately approved the deal. Kraft now had two sizable and distinct businesses—groceries and snacks. The acquisition gave Kraft’s snacks business enough scale to thrive in the competitive environment on a standalone basis and clarified the business’s value for investors. The company spun off the snacks business, renamed Mondelez, in 2012.

Use Transformational Deals to Stay Ahead of the Curve

Consumer behaviors and demands are constantly changing and disrupting industries. If you anticipate such changes in your industry, consider using downturn acquisitions to transform your business and adapt to the new environment. But be aware that the existing M&A toolbox might not be sufficient for transformative dealmaking. You need to think about deals in nontraditional ways, often from the perspective of creating a new ecosystem, building or participating in a collaborative network, or engaging in other nontraditional forms of cooperation. In this context, strategic partnerships, corporate venture capital, joint ventures, and minority M&A deals may be more effective than traditional acquisitions.

An example of forward-looking, transformative M&A in a downturn is BlackRock’s acquisition of Barclays Global Investors (BGI) in 2009. Through the acquisition, BlackRock expanded from its core business of active management into passive-investment management. BGI included iShares, a leader in exchange-traded funds (ETF). The iShares ETF business had high recurring revenues and low capital requirements. BlackRock accurately predicted that ETF would have a major impact on the asset management industry. In the decade since it acquired BGI, BlackRock has grown to become the world’s largest fund manager.

Instead of adding to an existing business or moving into adjacent ones, a company can use M&A to change its value proposition in the market, sometimes radically. A variety of external forces may compel such moves. These forces include rapidly changing customer behaviors (for example, the sharing economy), newly emerging business models (for example, robo-advisory in wealth management), and technological advancements and disruptions (for example, smartphones and 5G mobile networks). Such developments have the potential to drastically reduce or shift traditional profit pools.

Deals made in anticipation of, or in reaction to, these forces have a variety of rationales. A buyer can tap into emerging revenue streams and profit pools. It can also acquire skills and capabilities that complement those it possesses and are necessary to develop an offering that addresses changing customer needs. First movers can often capture the bulk of the benefits, especially if the new products or services are scalable or enabled by new technologies.

A few industries have already undergone or are in the midst of such transformational changes. Prominent examples are retail, media and entertainment, and automotive. Additionally, a number of other industries—including financial services and energy—face potential disruptions from nontraditional entrants attacking traditional profit pools. For example, oil and gas companies must find alternative sources of revenue in response to the increasing scarcity of natural resources and the shift to renewable energy.

Corporate decision makers in affected industries should view such radical changes, combined with the potential for a recession, as opportunities for transformative dealmaking. The downturn might be the best time to acquire the targets needed for a transformation, possibly at a discount. Downturn M&A enables companies not only to react to a changing environment but also to accelerate out of the recession when the economy gains traction.

Downturns are challenging times to manage a business. As executives focus on short-term headwinds, they must not lose sight of their longer-term strategic objectives. Dealmakers play a critical role in ensuring that the pursuit of long-term value creation continues. They can help the company take advantage of downturn opportunities—such as lower valuation multiples and targets’ lower standalone profitability during crisis times—to position itself for profitable growth during the recovery. To accomplish this, it is essential to be bold and stay the course, even in the face of negative investor sentiment. The bottom-line advice for succeeding with M&A in a downturn is clear: Get off the sidelines and into the game, but make sure you are prepared to win.