Banks will play a central role in unlocking the $3.8 trillion in annual investment needed to power the push to net zero. As a result, they will have an outsized influence over whether the transition to green is a just transition—meaning that costs and benefits of climate action are equitably distributed across society and do not create unintended environmental consequences. A just transition is not only important for society broadly but has business implications for large financial institutions.

Banks that identify where and how they can mitigate the negative impacts and maximize the positive dividends of the shift away from a carbon-based economy stand to garner real benefits. First, they will reduce regulatory and reputational risk to their business. Second, they will have an opportunity to tap into increasing government incentives and public-private funding opportunities aimed at driving a just transition. Third, they will be well positioned to seize new opportunities, including expanded business with clients that are themselves looking to address the social implications of their own climate transition.

Yet today, few banks are effectively integrating social considerations into their net-zero strategy. A global BCG survey of more than 250 banking executives with oversight of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues found that while 90% of respondents said it is very or extremely important to consider social impacts of their bank’s climate activities, only 33% reported that social considerations often or almost always impact decisions related to climate.

Today, few banks are effectively integrating social considerations into their net-zero strategy.

Based on our work with clients and engagement with other actors within the banking industry, we have identified some of the most important areas in which bank activities can support positive societal impact while also advancing both climate mitigation and adaptation and resilience (A&R). Among these areas: helping to minimize negative employment impacts from the loss of jobs in high-emitting sectors and supporting equity and accessibility in the emerging green economy. Leveraging that insight, banks should revisit their climate transition plans to identify where they need to mitigate negative social or environmental impacts and where focusing on a just transition creates new opportunities.

The Just Transition Imperative

Many banks are actively engaged on decarbonizing their portfolios. In addition, forward-looking banks are also increasingly focused on how they can improve the positive impact they have on society. The issues around just transition sit at the intersection of both efforts.

The concept of a just transition applies to the two primary categories of climate-related actions: mitigation and adaptation and resilience. Mitigation, which encompasses actions taken to reduce or eliminate carbon emissions, has the potential to negatively affect some groups in society or create unintended negative environmental impacts. The second set of activities relate to steps to address the negative impact of climate change on society, what is known as A&R. Many of the existing disadvantages faced by vulnerable groups such as women and children in low-income countries are and will continue to be exacerbated by climate change. Consequently, A&R actions are necessary to ensure that climate change does not compound existing economic injustices. (See sidebar, “The Impact of Net Zero Goes Beyond Climate.”)

The Impact of Net Zero Goes Beyond Climate

The Impact of Net Zero Goes Beyond Climate

The decarbonization of the global economy can create both benefits and negative impacts in each of these categories:

- Workforce transition and labor rights. The International Energy Agency (IEA) expects the energy sector transition and proliferation of new green economic activities will create 25 million net new jobs by 2030 compared to 2019. For workers in industries that will be hard-hit by the transition, there is an opportunity to be reskilled to meet the requirements of those new positions. However, some 5 million jobs in heavy emitting industries (think petroleum refining or coal mining) are projected to be lost, with certain regions at risk of being heavily impacted by those losses. That does not include jobs that are at risk due to the environmental degradation spawned by climate change, including loss of fishing stock or a decline in tourism. In addition, exploitative labor practices have been identified in the value chains of many green products, including in solar panel production and the extraction of minerals for electric battery production. As demand for those green products increases, such problematic labor issues may become more prevalent.

- Accessibility and equity. On the plus side, the IEA expects that achieving net zero by 2050 could unlock universal energy access, with 80% of those gaining energy access doing so via renewables. However, some green products and services may come at a premium initially, putting those offerings out of reach for low-income households. At the same time, SMEs may be less able to decarbonize their supply chains and low-income countries that are unable to develop green industries could fall behind economically. Meanwhile, physical impacts of climate change are often projected to be most acute in areas with a high concentration of people earning low incomes. Without careful consideration of that dynamic, A&R investments can worsen conditions for those populations. Case in point: the construction of a levee to improve adaptation and resilience in a particular part of a community may worsen flooding in another area of that community.

- Land and community rights. The net-zero push will play out very differently in different regions, cities, and communities, with the impact extending far beyond jobs directly gained or lost. Some communities will enjoy an expanding tax base and a growing economic base supported by the growth of new green industries such as renewable energy. Other communities, meanwhile, can experience the opposite. For example, the accelerated closure of a coal plant that accounts for the lion’s share of a town or city tax base could disrupt the provision of social services and the maintenance of critical infrastructure. In addition, there are indigenous and other communities that maintain a high dependence and close relationship with the environment and its resources. Consequently, some mitigation and A&R activities, if not properly designed, have the potential to disrupt the economic, cultural, and societal relationships these groups maintain with the natural environment.

- Natural resources and planetary boundaries. There is a growing recognition that man-made activities are straining the natural world.

Planetary boundaries represent a set of environmental change processes that regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth systems, including climate change, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, and others. Many public and private sector players are using nature-based solutions such as afforestation as part of their net-zero strategies. Such efforts can have major benefits beyond climate. Regeneration of peatlands and mangroves, for example, not only sequester carbon, but also boost biodiversity growth. At the same time some actions that contribute to carbon emissions reductions, when not managed properly, can have potential negative impacts. Afforestation through ranch conversion, a mechanism that can be used to generate carbon credits, can threaten agricultural productivity and farmer livelihoods. Mishandling of metal mining for batteries can lead to severe water and air pollution. And hydropower dam development, which creates renewable energy, can also cause irreversible harm to wildlife and biodiversity—lowering fish catches and damaging biodiversity of nearby sites.

For banks, like for other companies, negative social outcomes often occur as a secondary effect of making good decisions on climate. For example, as banks incorporate climate risk into credit risk models, they may end up unintentionally disadvantaging people living in low-income communities, which are often located in climate hazard-prone areas.

The inaction by banks on just transition reflected in our recent survey stems in part from the fact that, until recently, there has been little in the way of guidance or incentives to do so. However, momentum is building with new regulations, policies, and guidance emerging around the world.

In the US, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and the earlier Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) allocate nearly $480 billion in federal funding to climate measures in the form of infrastructure grants and tax credits. In order for banks and corporate clients to access incentives offered under the IRA, they must show that they contribute to certain social benefits. For example, the IRA extends an increased credit amount to renewable energy projects that are developed in an area with historically significant levels of employment relating to the fossil fuel industry. Banks that are more advanced in embedding social considerations into their climate financing activities stand to help their clients take advantage of these types of fiscal initiatives.

The European Union’s Green New Deal established a €17.5 billion Just Transition Fund to help territories most affected by the transition. It also established a budgetary guarantee arrangement aimed at mobilizing private sector funding for infrastructure projects in territories in the EU that currently host CO2-intensive industries. In addition, the proposed Green Deal Industrial Plan—the EU’s response to the US IRA—establishes training and reskilling as one of its four main pillars, recognizing the importance of workforce skills enhancement in ensuring a just transition as decarbonization accelerates. And in the UK, the government’s Transition Plan Taskforce has announced it will release just transition guidance sometime this year. In addition, European regulators are readying new sustainability reporting requirements for companies—not just financial institutions. (See sidebar, “Europe Raises the Bar on Sustainability Reporting.”)

Europe Raises the Bar on Sustainability Reporting

Europe Raises the Bar on Sustainability Reporting

In November 2022 the European Commission approved the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) aimed at improving the quality and consistency of ESG reporting. The European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) is charged with developing the reporting standards required to meet the objectives of the CSRD. In addition to environmental and governance standards, EFRAG has set standards for social reporting that covers the social impact of a company’s business on its own workers, but also on workers in the value chain, affected communities and consumers and end-users of its products.

The new rules, expected to be in place for 2024 reporting, will apply to all large and listed companies in Europe. That will include many international companies that operate in the EU. As a result, all large companies operating in Europe—including global financial institutions—will need to up their game in tracking social metrics that are material both in terms of the financial impact they have on the business and the impact they create more broadly.

Meanwhile, several governments have joined forces over the last few years to create several Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), alliances that include funding and investment plans to advance decarbonization in a way that supports equity in society. To date, JETPs have been created for Indonesia, South Africa, and Vietnam. The Indonesia and Vietnam JETPs specifically call for the private sector to provide half of the necessary funding. Although the South Africa JETP does include targets related to helping workers become skilled for the new green economy, the primary focus for the JETPs is ensuring adequate funding to help these countries decarbonize. As detailed investment plans begin to emerge, equal attention should be paid to putting additional thoughtful, social safeguards in place.

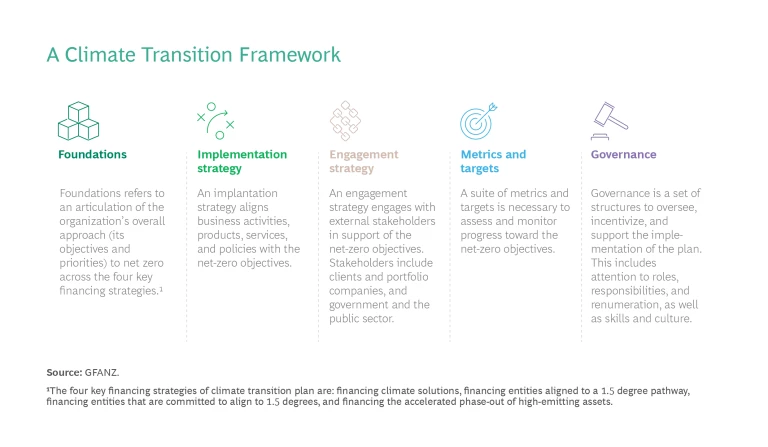

At the same time, industry groups are also coalescing around how to make a just transition reality. For example, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), a coalition of leading financial institutions, created a framework for Net-Zero Transition Planning and has urged financial institutions (insurers, banks, and asset managers) to take a leading role in ensuring the net-zero transition happens in an equitable way. More recently, the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment has made recommendations on how to embed just transition considerations within the five elements of the GFANZ

How Banks Can Support a Just Transition

There are many approaches for banks to develop a climate transition plan. Here, we use the GFANZ framework as the basis for exploring how banks can ensure that social considerations are integrated into these

To get started, banks can ask a series of questions:

- On foundations: Do our objectives and priorities of the climate transition plan include supporting a just transition? The GFANZ framework identifies four transition financing strategies: financing climate solutions, financing entities aligned to a 1.5°C pathway, financing entities that are committed to align to 1.5°C, and financing the accelerated phaseout of high-emitting assets. The framework recommends that banks prioritize those strategies where they can have the most impact on emissions reductions. As banks do that, they should ask themselves what the just transition implications are for those strategies. For example, financing new climate solutions might raise human rights issues in the supply chain of new companies while financing to phaseout high-emitting assets may raise issues around displaced workers.

- On implementation strategy: Have we embedded social considerations into all aspects of the business that connect to climate? This should include assessing whether our existing offerings create unintended, negative social impacts—and what could mitigate such issues. Banks should also consider if social considerations are incorporated into their decision-making processes—from lending agreements to investment strategies. They also need to examine whether there are policies, for example those for integrating climate impact into risk models, that contribute to inequity—and if so, how to adjust them.

- On engagement strategy: Are we actively engaging with stakeholders to assess the social impact of their own transition activities? Banks need to evaluate how they are working not only with clients and portfolio companies but also within the financial services industry to drive action on just transition. And they can look for opportunities to collaborate with government to ensure the net-zero transition does not increase social inequity.

- On metrics and targets: Are we tracking metrics on the impact the bank’s focus on equity in climate transition is actually creating? Such metrics could include job losses averted or percent of funds invested in women- and minority-owned green tech businesses.

- On governance: Are there siloes between our climate and social activities? To eliminate these siloes, banks need to think through how to bring both climate pros and experts on social issues such as human rights and gender equity onto climate transition teams. It also means investing time and resources in building the right culture and skillset to ensure its actions advance a just transition.

To effectively put the framework into action, banks must bring it down to the individual business units. And that is the area where we see a gap. In conversations with bank executives, we often hear questions about what they would need to do differently at the business unit level to integrate social issues into their climate transition plans. To help answer those questions, we took a close look at concrete actions banks can take to advance a just transition in wholesale and capital markets, retail and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and asset and wealth management.

Wholesale and Capital Markets. Banks have a significant opportunity to shape the social impact of the net-zero transition through their role helping business clients raise either debt or equity financing. Notably, respondents to our global market study ranked wholesale and capital markets as the most important business unit for incorporating social considerations into climate financing activities.

For example, they should ensure that the companies for which they provide financing services are themselves factoring just transition principles into their activities. That might include ensuring that any mining company they work with that is building its green minerals business also has a strong worker protection record or that adjustments to an agricultural supply chain made in anticipation of future climate change impacts do not unnecessarily deprive farmers of their sole source of income. There is also an opportunity to incorporate just transition KPIs directly into fixed-income products. Among the possibilities: sustainability linked bonds can include interest rates that are linked to a range of environmental and social KPIs.

At the same time, factoring just transition into a bank’s climate transition plan will by necessity result in different policies in developing versus developed markets. For example, banks set policies for what they consider to be a “transitional activity”—financing they provide to support a shift toward an activity that has lower-emitting but is not fully green. Transitional activities will be different in the low-income versus high-income countries given that the latter are much further along in deploying large-scale renewable power. As a result, it might be appropriate to consider a switch from coal-powered energy to gas-powered energy in a low-income country to be a transitional activity—but not appropriate in a high-income country.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on financial institutions

Retail and SMEs. Banks have a major part to play in ensuring accessibility and equity, both in terms of access to emerging green products and how they integrate climate risk into existing offerings. Consider green mortgages, loans that often come with slightly lower than average rates and are designed to finance energy efficient homes. Low-income borrowers are less likely to have an energy-efficient home—and therefore typically would have less access to green mortgages. Similarly, low-income households are more likely to face heightened climate risk and require financing to increase the protection of their homes against climate hazards. As banks increasingly factor climate risk into their credit processes due in part to regulatory requirements, there is the potential for low-income borrowers to become even more disadvantaged.

Banks will also have an opportunity to support small and medium-sized enterprises in the new green economy. SMEs do not have the same resources as large corporations to decarbonize and therefore risk losing competitiveness. That dynamic has a direct impact on the livelihoods of SME owners and employees. Banks can support SMEs in a number of ways, including offering programs to raise awareness of changing regulations and technologies and introducing specialized financing products to support SME decarbonization or the development of new green offerings.

Asset and Wealth Management. Through their investment arms, banks have an opening to influence how large companies and public sector organizations around the world integrate the just transition imperative into their own operations.

As part of an ESG integration strategy, many asset and wealth management units within large banks have been integrating social factors into investment decisions. However, when constructing clean energy or other climate-focused investments, they may not be integrating social into these funds as rigorously as possible. For example, an asset and wealth management arm that is investing in battery or solar panel industries should recognize that these sectors are known to have human rights issues in the supply chain and should (and in Europe may soon be required to) screen specifically for these social issues before investing.

For existing investments, asset managers can engage with portfolio companies to factor social risks and benefits into their net-zero plans. They can use shareholder filings of the companies in their portfolios to push for action on a just transition, for example asking companies to factor indigenous rights into their activities. Where divestment in a high-emitting holding is warranted, asset and wealth managers can ensure that just transition issues are addressed before exiting their investment. And they can identify and invest in companies that are helping to drive a just transition, for example real estate or infrastructure players that are investing in regions negatively impacted by the energy transition.

Leading banks are aggressively pushing to advance the global drive to net zero. Given their central role in the global economy, scrutiny will inevitably increase on whether their actions are supporting—or undermining—inequities in society. Right now, coal-phase out commitments and concrete interim targets are now seen as best practices in net-zero transition planning. It is likely that building just transition strategies into a bank’s net-zero implementation plan will become the next gold standard.

As the net-zero transition accelerates, the social implications are becoming clear. In some parts of the world, the potential negative impacts on certain communities have been put forth as a justification for opposing climate measures. However, there are also cases in which putting people and communities at the center of climate policies has resulted in greater and more durable momentum and buy-in for climate action. Banks can play an important part in ensuring climate action is both ambitious and human centered.