As Latin America heads for the worst recession in its history, consumer packaged goods (CPG) manufacturers must guard against the decimation of their distribution networks in the region.

Convenience stores, restaurants, and bars in Brazil, Mexico, and other Latin American countries will face enormous pressure as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Up to 25% of convenience stores and 80% of bars and restaurants could close—imposing a new kind of suffering on a region that is already contending with more than 4 million infections and 160,000 deaths.

The disappearance of so many of these small points of sale will have a big impact on CPGs, which count on this “traditional trade” for the vast majority of their Latin American sales. Traditional trade is also a much more profitable channel for CPGs than the modern trade channel, which includes the up-and-coming atacarejo format in Brazil and supermarkets everywhere.

No matter what they do, CPGs won’t be able to avoid the disruption completely. But they have a chance to shape how traditional trade will look after COVID-19 has run its course and to ensure that these outlets remain a significant contributor to their success in the region.

THREE WAYS TO HELP THE TRADITIONAL TRADE

Here are the three main actions that CPGs should be taking today.

Provide Guidance on Best Practices for On-Premises Safety and Cleanliness

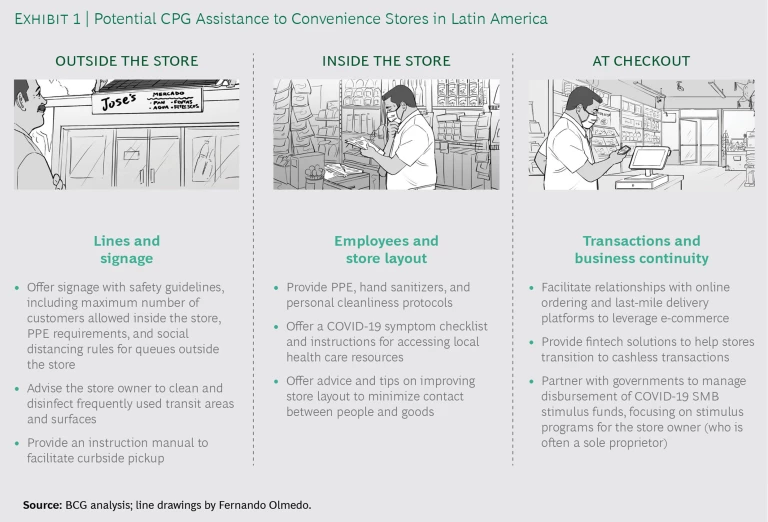

Most people who own small and medium businesses (SMBs) in Latin America don’t have the resources or the business sophistication to figure out how to change their selling environments in response to a serious health crisis. They could use help with every step of the selling process—from the SKUs they carry, to the store layout they adopt, to the protective devices they use, to the types of payment they accept.

For SMBs that haven’t yet made significant changes, it’s not too late to begin. Many of the safety changes that today’s conditions demand may still be needed a year or more from now.

Although important throughout Latin America, the guidance is especially critical in countries where reopening guidelines and policies have so far been less strict and have left shoppers unsure of where they can shop safely. Those countries include Brazil (which crossed the 68,000-death threshold this month) and Mexico (whose requirements on mask wearing and social distancing have been lax and whose daily death rate is still rising).

In every Latin American country where they do business, CPGs need to play the role of safety advisor. Some are already doing so. For example, Pepsi, Coca-Cola, Mondelez, and Kellogg have teamed up with trade associations on an initiative called Mi Tienda Segura (“My Safe Store”). As part of this initiative, neighborhood stores and grocers receive tips through Whatsapp about how to ensure that their stores are safe to visit and how to avoid worsening local contagions.

Much of the guidance should relate to what happens in and around the SMBs’ physical locations. To begin with, they should emphasize cleanliness protocols that employees should follow—from frequent hand washing to sneezing (when necessary) into the crook of an elbow. The advice on sneezing is among the practices that Walmart Mexico is reminding workers about in its stores. Small-store employees would also benefit from handouts describing symptoms and steps to take in the event of illness.

Proper attention to personal protective equipment—including gloves and masks—is another way for a store to demonstrate its safety awareness. CPGs are in a position to ensure that their points of sale have a steady supply of this equipment. In Mexico, the brewery company Grupo Modelo has taken practical steps in this area by making and distributing 300,000 bottles of hand sanitizer.

SMBs should also adopt sensible social-distancing practices. These could range from limiting the number of shoppers in a store at any given time to displaying signage that helps people maintain a safe distance while lining up outside or in checkout areas inside.

Other steps could help minimize the chance of contagion in other ways. For instance, CPGs could restructure their packaging and delivery processes to decrease the number of touches that occur between a warehouse and a point of purchase (or consumption). They could suggest ways of making low-contact curbside or in-store pickup easier. And they could encourage their traditional-trade partners to sell in the open air—in adjacent parking lots, for instance—where transmission of COVID-19 is much less likely. (See Exhibit 1.)

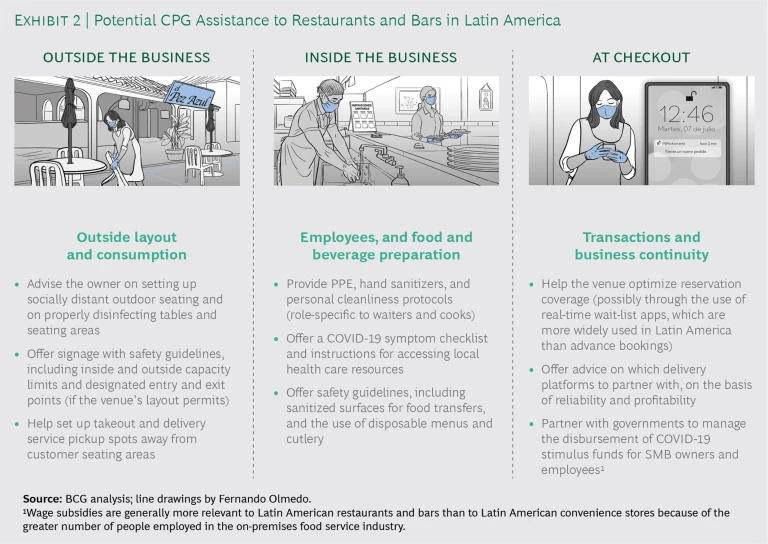

Some of these same tactics—including limiting the number of visitors at any given time and increasing the availability of open-air service—would make sense for on-premises food service establishments as well. CPGs could help restaurants think through their options. CPGs might also work with local governments to help turn sidewalks into outdoor eating and drinking areas.

Help SMBs Accommodate the Shift to Online Buying

Many consumer habits that have emerged during the pandemic will never completely revert to what they were before the advent of COVID-19. For example, e-commerce jumped fivefold in China after the SARS crisis in that country. SARS marked the beginning of a behavioral shift in China that has intensified.

COVID-19 may have a similar catalyzing effect in Latin America, where the habit of buying at local stores has until recently been deeply engrained in consumer behavior. Indeed, the shift to e-commerce is already occurring. Argentina’s Mercado Libre marketplace added 1.7 million new customers within a few weeks of the World Health Organization’s declaring COVID-19 a pandemic. And just one month after Latin American countries began to shut down, e-commerce purchases in the region had risen by a factor of five, according to one estimate—a near-identical repeat of SARS’s impact in China a couple of decades earlier.

The surge in e-commerce in Latin America is evident in the increased visibility of last-mile delivery services. Barely six months ago, Rappi, a Colombia-based network of app-enabled couriers, was instituting layoffs. Today, those layoffs seem like a distant memory. Rappi’s orange-clad delivery people are everywhere—from Mexico City to Bogotá to Santiago—delivering everything from groceries to restaurant takeout food to beer and wine.

Another indication of e-commerce’s rise in Latin America is Tiendita Cerca. Previously a platform to help consumers locate nearby stores and products, Tiendita Cerca has morphed into an ordering platform. Today, someone sitting at home in Guadalajara can use Tiendita Cerca to order a few necessities from a nearby store and then pick up the order, reducing time in the store and exposure to other shoppers.

For now, this use of Tiendita Cerca is only available in a few cities. Still, it shows that Latin American consumers are ready for something new.

Other, more ad-hoc forms of e-commerce have risen in prominence as well. For instance, numerous enterprising delivery people, unaffiliated with any company, offer to take product orders over Whatsapp or Facebook Messenger from neighbors living in their town or city and deliver the products on a scooter or bicycle. This informal channel (we call it the “conversational sale”) has existed in Latin America for some time, but its importance has grown significantly during the pandemic.

Suppliers can take the lead in helping SMBs use these platforms to thrive in this new world. They should educate SMBs in how to use fintech solutions and digital marketplaces for online ordering. It’s also possible that some B2B sales tools that CPGs use (such as Grupo Modelo’s MiMercado, which tracks SMB sales and deliveries) could be adapted to facilitate B2C transactions.

A capability in digital transactions isn’t only important in situations where the buyer never sees the seller directly. The same capability will become increasingly important for in-person store transactions, too—for instance, when someone comes up to the window of a grocery or picks up a food order at a restaurant in Lima. Customers may not want to hand Peruvian soles back and forth; they may instead prefer to complete the transaction digitally. (See Exhibit 2.)

Cashless payments have caught on in Latin America in response to the coronavirus, and they won’t disappear anytime soon. In a survey that MasterCard conducted in April, four in every five Latin Americans said that they would continue to use cashless payments after the pandemic ends.

Consumers’ shifts toward e-commerce and digital transactions may also add urgency to CPG’s investments in Latin American fintechs. So far, much of the increased use of fintechs (including downloads of digital wallets and signups at neobanks) has occurred among Latin America’s banked population. If more of the unbanked population starts using fintech technology, CPGs will want to have a hand in shaping that development.

Play a Role in Ensuring Distributor Liquidity

To survive the downturn that is gripping the region, many Latin American SMBs will need direct financial assistance. Some CPGs are already providing this, by relaxing their usual payment terms with stores and restaurants. This is a way of helping SMBs manage their working capital needs.

CPGs may also be able to play a role in SMBs’ receipt of government stimulus money. In Brazil, the amount approved for distribution to SMBs is about $7.5 billion. In Argentina, the SMB-specific relief money (which includes lines of credit for working capital) is around $5 billion. Colombia’s stimulus plan includes $500 million for emergency SMB loans and $100 million in emergency funds for microbusinesses.

Processes for transferring government money to small businesses during a crisis are never simple. Even in the US, with its highly developed financial infrastructure, the process for disbursing coronavirus relief funds to businesses has been hampered by delays and has elicited criticism.

The processes in Latin America are likely to face even bigger obstacles, as the informality of the traditional trade sector complicates decisions about eligibility. As those who sell through traditional trade channels in Latin American know, a significant number of SMBs aren’t registered with the government. And because national governments don’t include unregistered SMBs in their records, officials have no way of telling, for instance, which of the hundreds of SMBs within a 5-square-mile radius of a densely populated city are most important to the local economy.

CPGs that distribute directly rather through middlemen are much more likely to have this understanding. Governments in Latin America recognize this, which is one reason why they have been approaching local CPGs to get their help in allocating relief funds. A number of scenarios are possible. For instance, CPGs could directly disburse government loans to SMBs—or they could partner with local development banks or supranational organizations such as the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank to funnel loans to SMBs. In some cases, CPGs might want to make loans to certain SMBs directly, with flexible repayment terms.

To the extent that CPGs are involved in the fund dispersal process, the onus will be on them to identify the SMBs that have the best prospect of thriving in the long term. This does not mean CPGs should neglect struggling SMBs. But they need to prioritize those that have the best chance of coming through the crucible of COVID-19 intact—or even strengthened.

A DUTY AS WELL AS A BUSINESS IMPERATIVE

It would be ideal if CPGs had a perfect understanding of how things will shake out in Latin America’s traditional trade. Alas, no such clarity is possible. What we do know is that, a year from now, there will be many fewer tienditas, mercados, restaurantes, and bares. This will be devastating for the tens of millions of people for whom these businesses represent a livelihood.

CPGs can’t contain the damage to this critical economic sector all by themselves. They are just one actor—alongside local governments, multinational organizations, and others—with a role to play. But their contacts, business skills, and intimate knowledge of individual points of sale put CPGs in a unique position to offer valuable support for traditional trade.

We hope they will do everything they can to help. To a degree that isn’t usually true in business, we are all in this together.