Unprecedented times call for unprecedented measures. Oil and gas operators are reeling from the effects of the pandemic as well as collapsing oil prices. In addition, worldwide lockdowns and border closures are hampering the ability of oilfield services and equipment (OFSE) suppliers to deliver on time and on budget.

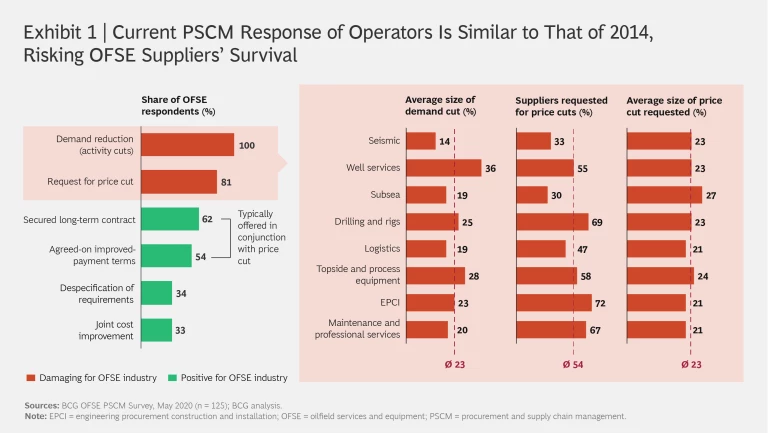

Many OFSE companies are entering this crisis weaker than they’ve ever been. Despite this, oil and gas operators are demanding that suppliers cut prices and are reducing both operating and capital expenditures, as they did during the 2014 price decline. Such traditional measures could cause supply companies to go bust, decimating vital industry capabilities and hurting the ability of oil and gas operators to maintain production.

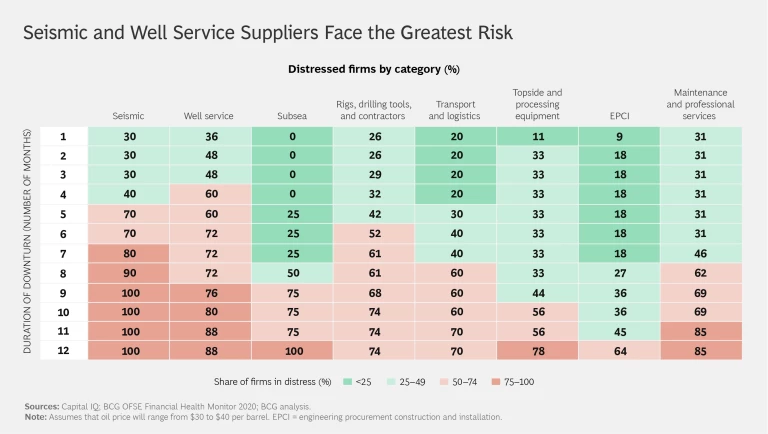

Operators must adopt a radical dual approach. In the short term, they need to take steps to protect OFSE companies and enable industry supply chains to continue functioning. Assuming that the oil price stays below $40 per barrel and disruptions to manufacturing and logistics caused by the pandemic continue, we estimate that nearly half of all OFSE companies—and up to 90% of seismic-services suppliers and 70% of well services companies—could go bankrupt six months from now if operators don’t implement such supportive measures.

At the same time, oil and gas operators should view the crisis as an opportunity to transform commercial relationships in the medium term and apply lessons from other industries in preparation for an imminent lower-for-longer oil price environment. By responding to the new reality and selectively partnering with their suppliers, companies can build resilience and unlock sizeable savings.

By responding to the new reality and selectively partnering with their suppliers, companies can build resilience and unlock sizeable savings.

Suppliers Have Never Been So Vulnerable

OFSE companies are facing a business environment that is harsher than in any previous downturn. As a result, several leading suppliers have already filed for bankruptcy protection. To better understand the difficulties confronting OFSE companies, we surveyed senior managers at 125 tier one supplier organizations, conducted CEO interviews at more than 30 of those companies, carried out financial analysis of over 200 suppliers, and analyzed spending by operators across all main basins.

Our key findings are as follows:

- OFSE companies had significantly greater leverage in 2019 than they did in 2014, with higher interest charges eating into their cash flows. At the same time, they had far lower operating margins, with some supplier margins in negative territory.

- Our analysis of different operating basins indicates that operators will need to reduce unit costs by 20% to 50% to break even.

- Four-fifths of OFSE suppliers have received requests from operators to cut prices by 20% to 25% during the current crisis.

- Tier one suppliers expect around 40% of their subsuppliers to face a significant risk of bankruptcy if the oil price is between $30 to $40 per barrel in the fourth quarter of 2020.

Our findings indicate that operators are often failing to recognize the level of financial distress in their supply chains. Many are still using the traditional cost-cutting measures that they’ve used in previous crises. But this time, these measures are not only inadequate for achieving the depth of cuts needed to break even, but they are also jeopardizing their suppliers’ continued existence. (See Exhibit 1.) Consequently, operators will have to think and act more creatively to achieve the savings they require.

Get Ahead of the Game

Ordinarily, supplier distress is not a significant issue. Operators typically check OFSE companies’ financial details during the qualification process for new suppliers and before they award large contracts. And until now, operators have faced only a few instances of triggered force majeure clauses and supplier bankruptcies per year in various parts of the world. However, in the current crisis, which combines an oil price shock with pandemic-induced logistics and manufacturing disruptions, widespread supplier distress is a reality and large operators can face dozens of force majeure incidents and bankruptcies every month.

As a result, operators need a deeper and more forward-looking understanding of their suppliers’ financial health in order to anticipate and react quickly to potential problems. This is especially important when the suppliers involved are critical for business continuity.

Using financial metrics and analysis that create a more forward-looking picture allows operators to take a differentiated approach with their supply base, to use a broader and more collaborative range of measures, and to buy time.

Typically, most operators assess supplier risk by looking at a variety of financial metrics that are at least three months out of date. These include liquidity, debt-to-equity, and interest coverage ratios; credit ratings; and Altman Z bankruptcy scores. While these metrics were sufficient prior to the pandemic, they are no longer effective in today’s dual-shock crisis. At BCG, we have built a model to monitor the health of individual OFSE companies that starts with this information but then goes further, allowing us to predict future difficulties.

How the Supplier Risk Model Works

After assessing historical financial data, the next step is to get a better understanding of suppliers’ financial outlooks in light of industry dynamics. For example, by examining how oil price changes have impacted demand for various supplier services in the past, we can analyze the vulnerability of individual suppliers’ revenues in the current crisis. Using operator announcements, we can assess the likelihood of revenue losses for different OFSE categories in different basins. By examining market concentration for suppliers in different categories, we can determine any given company’s ability to absorb revenue declines and protect its margins. And by analyzing other leading indicators, such as rig counts and information about project economics in different basins, we can identify industry stress points. (See “OFSE Hotspots for Financial Distress”).

OFSE Hotspots for Financial Distress

OFSE Hotspots for Financial Distress

Using a broad set of metrics, we found that the following areas and categories are most likely to be exposed in the current crisis:

- Well development in Asia, the Commonwealth of Independent States, and Latin America is most vulnerable to capital expenditure (capex) cuts.

- Surface installations and infrastructure in the Netherlands, in the Permian Basin, and on the US East Coast are also highly vulnerable to capex reductions.

- On a regional basis, Africa and North America face the highest risk of supplier financial distress and supply chain disruption.

- Companies that supply seismic and well services are most at risk of financial distress, and that risk increases as the downturn continues. (See the exhibit.)

The final step involves modeling the ability of OFSE companies to respond to changing conditions. For this, we look at the following metrics:

- Cash and cash equivalents, which indicate whether a company has healthy financial reserves

- The proportion of variable to fixed costs, which show how flexible a company’s cost base is

- A company’s debt ratios, which indicate whether the business will generate enough cash flow to service its debt

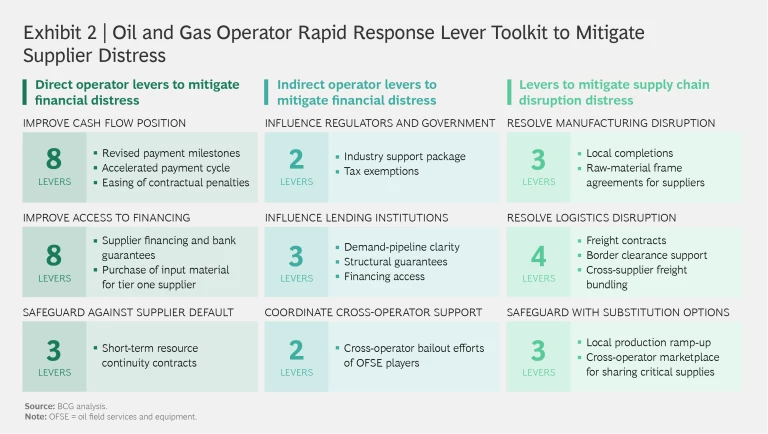

Armed with this information, operators can more effectively head off potential supply chain problems. We have identified more than 30 measures that can help operators support their OFSE suppliers, but less than 20% of them are currently being deployed. Operators should turn to these measures, particularly with regard to the OFSE companies that are most financially vulnerable and are essential for continuing production, such as well and subsea services, maintenance, and transport and logistics suppliers.

For example, in addition to such standard practices as extending credit lines and providing guarantees that help suppliers access external finance, operators should consider sharing freight capacity with suppliers, helping with border clearance for equipment and spare parts, and providing upfront payments to help suppliers fund input materials. (See Exhibit 2.)

But when considering mitigation measures to help suppliers through their financial distress, operators will have to strike a careful balance. For some categories—including engineering, procurement, and construction, which depends on large order volumes to support investment in technology and skills—they will need to allow for a degree of consolidation to enable players to create sufficient scale and improve plant utilization to survive in a more challenging environment.

By applying a wide range of measures across OFSE categories, operators will be able to stabilize their supply chains, address pressing financial problems among individual suppliers, and buy time for additional actions. Nevertheless, they will need to go further to foster innovation, structurally lower costs, and create a competitive advantage over the medium to long term. Our research and interviews suggest that developing strategic partnerships with a select group of suppliers will be an important way to achieve these goals.

Strategic Partnerships Are a New Imperative

“Never allow a good crisis go to waste. It’s an opportunity to do the things you once thought were impossible,” Rahm Emanuel, a US congressman and a former mayor of Chicago, has famously said. In the current crisis, operators and OFSE companies need to think ahead and create a new type of relationship that, over time, will enable players to survive in a low-price environment where margins are compressed.

Strategic supplier partnerships can deliver value of 30% to 50% in operators’ upstream operations.

Building deep relationships with suppliers and creating value holistically will be a key feature of the emerging landscape. We estimate that such strategic supplier partnerships can deliver value of 30% to 50% in operators’ upstream operations, well above the 5% to 10% savings that operators expect to achieve through traditional measures. The interviews we’ve conducted indicate that leading OFSE suppliers are already holding exploratory discussions with operators about strategic partnerships.

The idea of strategic partnerships is not new; consider, for example, the automotive and aerospace and defense industries. Focusing on value and not just costs, car makers worldwide have improved quality, reduced expenses, accelerated time to market, and achieved technological breakthroughs by closely coordinating manufacturing with their suppliers and carrying out joint R&D and planning over several decades. New manufacturers of electric vehicles, for instance, have improved strategic supplier partnerships by taking such actions as simplifying and standardizing manufacturing processes.

The benefits of using strategic partnerships to generate value through more standardized and modular operations are widely recognized in the oil and gas industry. However, they have not taken off. There are three main reasons for this:

- Operators have historically enjoyed big profit margins and have concentrated on boosting production and revenues—unlike OFSE companies, which are more focused on cost and maximizing margins, thus creating a mismatch of incentives and goals.

- National procurement guidelines have favored standard practices (such as the “three bids and buy” procurement method) over the more innovative approaches required by strategic partnerships.

- The oil and gas industry’s entrenched culture and ways of working (where operators effectively dictate terms to OFSE companies), along with the difference in cultural DNA between operators and OFSE companies, have prevented suppliers from collaborating with operators to innovate and create value.

We believe that oil and gas companies must learn vital lessons about supplier partnerships from other industries and apply them to their own partnerships. The current crisis provides the opportunity for operators and OFSE companies to act creatively to transform their relationships. Oil and gas strategic partnerships can create value in several ways. Furthermore, we believe that in highly regulated oil-dependent markets, where a significant reduction in industry costs is needed to meet government fiscal breakeven targets, it is imperative for regulators to revisit their procurement-competition requirements and encourage greater value creation and cost savings to benefit partnerships.

To make strategic supplier partnerships a success and maximize the benefits they offer, operators should prioritize the following actions:

- Understand the true financial health of your supply chain by creating a deep and forward-looking understanding of individual supplier companies.

- Identify two or three suppliers across key categories, where large pools of potential value could be unlocked, and pilot strategic supplier partnerships with them.

- Ensure that you have senior sponsorship, and then start small by focusing on entry-level partnership components, such as long-term performance-based contracts, to help build trust between operators and suppliers.

- Brace for the inevitable culture shock caused by the difference in DNA between operators and OFSE companies—while remembering that strategic partnerships are a key way to create significant potential value.

- Go further with the partnership over time by introducing more complex partnership features, such as joint design development and operations planning, as well as co-innovation.

With a nod to former US president and army general Dwight D. Eisenhower, one could say that battles, and even wars, have been won or lost primarily because of procurement and supply chains. This message is particularly relevant for the oil and gas industry today. The crisis has elevated the procurement function within operators, transforming it from a support role into a source of competitive advantage, and it has given chief procurement officers a seat at the executive table. These leaders now need to balance supply chain health with a value creation agenda and turn strategic partnerships into reality.