The capital markets and investment banking (CMIB) industry continues to try to navigate its way through a transformational period that requires tough strategic choices. Declining revenues, an extremely challenging regulatory climate, clients that demand higher service levels and more innovative products, a shifting workforce culture, and the need to forge meaningful business partnerships are common items on the agendas of senior management teams globally.

Read more on this topic

Global Capital Markets

Although the industry-wide revenue decline in 2013 was not dramatic, at about 2 percent, the largest revenue pool—fixed income, currencies, and commodities (FICC)—suffered a steep drop of 16 percent. This decline was offset to some degree by substantial rises in equity and investment banking division (IBD) revenues. But after-tax return on equity (ROE) remains under pressure, falling slightly in 2013 to 11 percent, with further declines probable in 2014. Overall, we believe that the industry’s focus on regulatory compliance and cost reduction, necessary as those activities may be, has worked somewhat against placing sufficient emphasis on improving core business capabilities and increasing revenues. As for regulation, the framework for the future has largely been set. It is the implementation of this structure that still has a long way to go—and that continues to generate uncertainty regarding both revenue models and costs.

With the outlook for revenue growth so dim, the industry winners will be those institutions that are able to increase market share. Several factors will be key to this battle. First, client centricity continues to be critical as a way to make relationships more comprehensive, more durable, and more fruitful both for the client and the bank. Second, CMIB institutions need to define what the investment banker of the future looks like—and to make sure they can attract the best and brightest. Such individuals will need a broad set of skills, an entrepreneurial and innovative spirit, and the ability to embrace a deep cultural sense of compliance and collaboration. Third, CMIB players need to investigate commercial partnerships in order to mitigate the revenue effects of retrenchment in certain regions and products.

In our 2013 report, Global Capital Markets 2013: Survival of the Fittest, we asked whether the CMIB industry could survive in the long term. Our answer then, as it is today, is yes, but tall challenges remain. In this, our third annual report on the global CMIB business, we take a deeper look at those challenges, particularly regarding the core dynamics—revenues, regulations, The Push for Client Centricity at Investment Banks, The Battle for Talent: Can Investment Banks Win?, and The Right Partnerships Can Help Investment Banks—that influence the six business models that we feel are most viable. Our aim is to provide food for thought for senior management teams as they refine their strategies.

Key Market Developments

We see two key challenges facing CMIB players. First, revenues have now become a scarce and volatile resource, pressuring short-term ROE. Second, regulation continues to take its toll and will remain a critical element as banks address cost structures, revenue models, and strategic positioning. Both revenue and regulatory dynamics will affect what we see as the six core business models in the CMIB industry.

The Revenue Challenge

ROE in the CMIB industry fell to 11 percent in 2013, a decline of 1 percentage point from the previous year. This level, which remains at or just below the typical cost of equity (10 to 12 percent), might seem relatively stable. But given the trend toward combined reporting of corporate banking and CMIB activities, appearances can be deceptive. For example, corporate banking activities—such as project finance, trade finance, and cash management—that have traditionally had low capital requirements and low cost-to-income ratios (around 35 to 40 percent) have contributed positively to ROE, potentially hiding decreasing profitability in pure capital-markets activities. Overall, the industry ROE has not returned to its precrisis levels, and the range of ROE outcomes for individual institutions has widened.

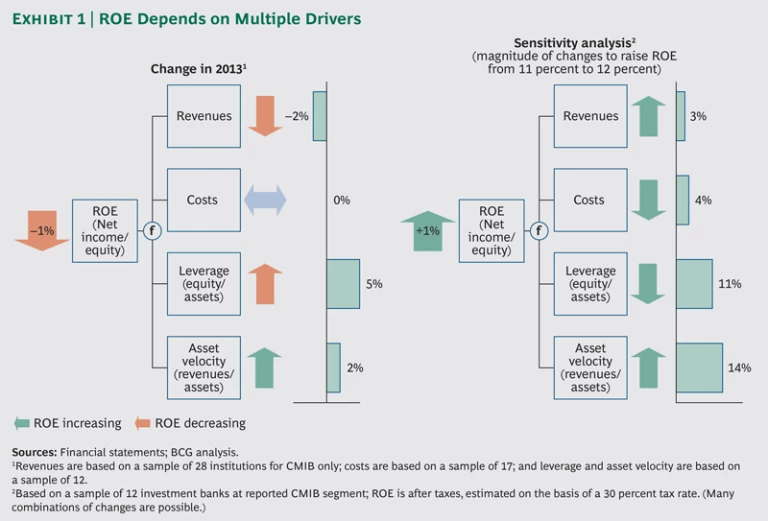

In order to fully understand the dynamics behind ROE, it is important to examine the principal ROE drivers: revenues, costs, leverage, and asset velocity. (See Exhibit 1.)

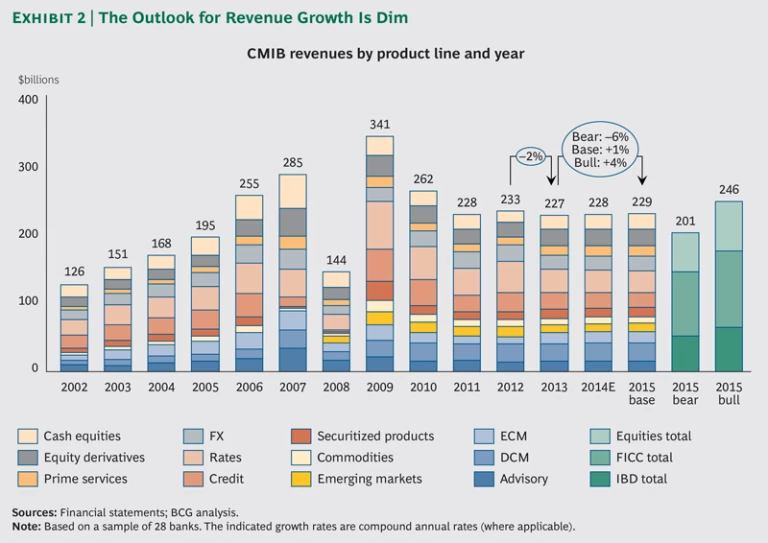

Revenues. CMIB revenues fell by 2 percent to $227 billion in 2013, and have declined by 13 percent since 2010. Pressure on margins has remained high across all asset classes as electronification has continued to expand, a trend that shows no signs of slowing. Even as some asset classes (such as equity derivatives) and cross-asset products show strong growth, they will not be able to offset the declines in other, much larger asset classes. Risk-taking, measured by value at risk (VaR), has continued to decline—dropping about 45 percent from 2010 to 2013 for the top nine players—with ever-decreasing inventories and lower revenues from market-making activities. Funding costs have gone up, partly resulting from more equity-based (as opposed to debt-based) funding to comply with regulations that mandate higher capital availability. We forecast compound annual revenue growth of between –6 percent and 4 percent through 2015. (See Exhibit 2.)

- FICC, the largest CMIB revenue pool at nearly half of the total, fell by 16 percent in 2013 to $112 billion. This represented the bulk of the 23 percent decline from its 2010 level and was driven largely by low client flows and low volatility. In the rates business, the move toward central clearing will exert further pressure on margins, while the anticipated rise in interest rates in certain parts of the world (notably the U.S.) could help improve client demand and increase volatility. Commodities revenues in banking will likely decline further as banks exit the space because of regulatory difficulties and as the business moves to physical players. In currencies (FX), despite the already-high level of commoditization, we expect further margin erosion (which could, however, be partly offset by volume increases stemming from global trade growth). In credit, future U.S. mortgage reform and the negative net supply from 2013, along with increasing M&A activity and investment spending, could spur growth. But downside risk remains high if credit trading increasingly takes place through indexes.

- Equity revenues offset the decline in FICC revenues to some extent, increasing by 21 percent in 2013 to $59 billion and stabilizing at their 2010 level. Growth in equity revenues in 2013 was driven largely by the 24 percent and 15 percent growth rates in cash equities and equity derivatives, respectively. However, we expect the commoditization and electronification trends in cash equities to continue in 2014, hindering further revenue growth. In equity derivatives, we expect further strength in 2014 as investors continue their quest for yield, but these potential gains will not be sufficient to offset the much larger revenue declines that are expected in FICC.

- IBD revenues rose by 11 percent in 2013 to $56 billion, reversing three straight years of declines. This growth was driven primarily by a 56 percent increase in equity capital markets (ECM) revenues, which offset a moderate decline of

2 percent in debt capital markets (DCM) revenues that resulted from depressed activity in credit markets. We foresee further modest increases in M&A revenues in 2014, which should create some second-order benefits for ECM and DCM revenues. Moreover, in anticipation of potential interest-rate increases, companies continue to issue significant volumes of debt. This trend will likely lose steam, however, and we expect a rebalancing with equity funding in the long run.

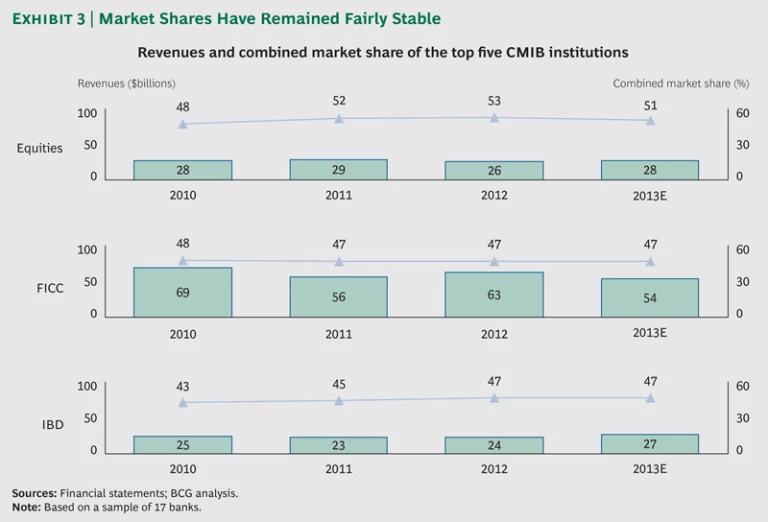

In a broader sense, we believe that the significant effort involved in meeting regulatory deadlines and reducing costs has somewhat sidetracked CMIB senior-management teams from putting sufficient focus on improving core business capabilities and driving revenue growth. Indeed, in a bearish environment with limited repricing opportunities, gaining market share is the only way forward. That said, we have not yet seen a clear trend toward consolidation, with the market share of the top five players in 2013 declining only slightly to 51 percent in equities and remaining stable at 47 percent in both FICC and IBD. (See Exhibit 3.)

Still, a number of Tier 1 players were able to capture a degree of market share, along with some Tier 2 and Tier 3 players that have shown remarkable resilience by refocusing on their core franchises—essentially, not trying to be everything to everyone. We expect more downsizing in the next couple of years in an industry that is still characterized by overcapacity. This trend will trigger new market-share and revenue-growth opportunities for Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 institutions alike.

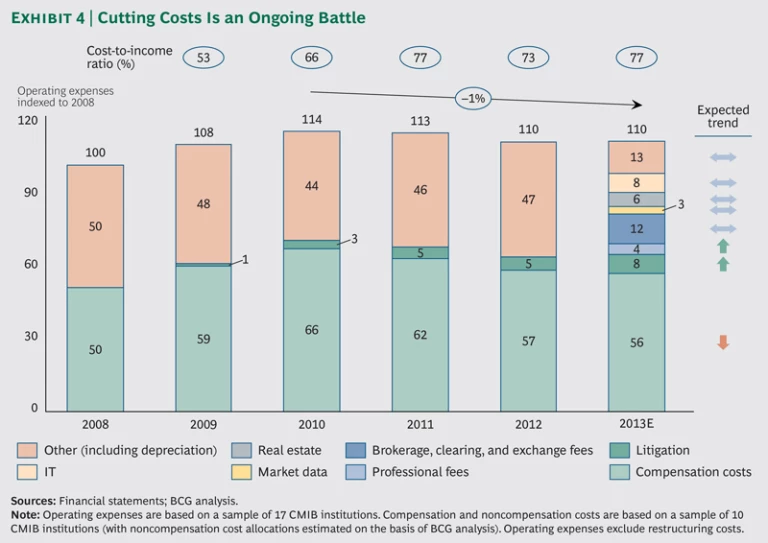

Costs. CMIB players continued to make progress on a number of cost reduction programs in 2013. (See Exhibit 4.) Compensation costs fell by 2 percent (and have declined by 15 percent since 2010), driven both by staff redundancies and by a decrease in average compensation (down 25 percent since 2010). Noncompensation costs (excluding litigation) also fell by 1 percent (but have increased by 4 percent since 2010). Total costs, however, have remained fairly flat, owing to rising litigation expenses, which increased from about 3 percent of total costs in 2010 to 8 percent in 2013.

Banks have seemingly reached an impasse of sorts, with the industry’s cost-to-income ratio remaining stubbornly above 70 percent—even rising from 73 percent in 2012 to 77 percent in 2013 (albeit with wide variation depending on the business model). We believe that still more can be done in areas such as simplifying organizational structures, standardizing processes, and increasing straight-through processing. Banks need to take significant action to break up silos and explore synergies across asset classes, and also to share or outsource infrastructure. Ultimately, we do not expect costs to decrease significantly, because banks will partly reinvest any cost savings to support new revenue initiatives—such as acquiring more front-office expertise and beefing up IT capabilities. Cutting costs by 10 percent would improve ROE by approximately 3 percentage points. Such a gain, however, would not be sufficient to return the industry to a sustainable level of profitability.

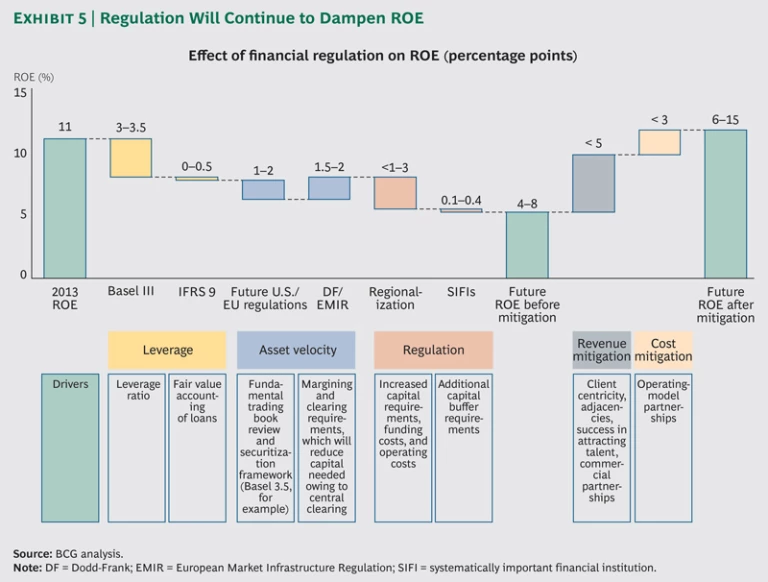

Leverage. As a result of Basel III regulations, leverage ratios (measured by the ratio of equity to total exposure) have been steadily increasing, from 2.4 percent in 2010 to 2.7 percent in 2012 and 2.8 percent in 2013. Leverage is no longer a tool for boosting ROE but a risk-based constraint that banks have to comply with. We expect further increases in leverage ratios, to as high as 5 percent (with differences between the U.S. and Europe), as a result of more stringent regulation-—leading to decreases in ROE of 3 to 3.5 percentage points. (See Exhibit 5.) ROE will likely take an additional hit of up to 0.5 percentage point as International Financial Reporting Standards regulations (IFRS 9) are applied to the fair value accounting of loans.

Asset Velocity. After several years of declines, asset velocity increased from 1.49 percent in 2012 to 1.53 percent in 2013, close to its 2010 level of 1.57 percent. The rise resulted from banks’ efforts to offset the impact of regulation by taking steps such as the following: continuing to exit activities that consume a high degree of risk-weighted assets; working on their risk methodologies; improving data quality; and increasing the internalization of client order flows. Size matters here, and the largest CMIB players benefit.

Looking ahead, the impact of Basel 3.5—specifically, the fundamental trading-book review and securitization framework—will continue to put pressure on banks that may have been more aggressive with their internal risk models and accounting treatments, while regulations on margining and clearing will reduce capital requirements. Consequently, we expect asset velocity to remain relatively flat in the coming years.

We should see further downward pressure on ROE in 2014 as several regulatory initiatives that stem from a systemic trend toward the regionalization of banking come into force. Regulators on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as in Asia, broadly aim to take the following steps:

- Require foreign banks to adhere to national regulatory regimes.

- Restrict the activities of national institutions in international markets.

- Limit cross-border, intragroup lending activities.

Overall, the impact will be varied, with some U.S. banks experiencing little impact (less than 1 percentage point of ROE) and others, such as European banks with sizable business in the U.S., feeling an impact of around 3 percentage points of ROE. Some European institutions have already announced significant reductions to their U.S. balance sheets because of the so-called Tarullo rules, which require them to structure their U.S. affiliates in a way that complies with the Dodd-Frank Act. We expect more European banks to follow suit.

Finally, we believe that revenues will be the key lever in restoring ROE. Successful CMIB institutions will increase market share and raise revenues by 10 to 15 percent, lifting ROE by up to 5 percentage points to approach 15 percent. In a bearish revenue environment, others will continue to struggle to meet the cost of equity.

The Regulation Challenge

Despite ongoing updates to banking regulations, the direction of the CMIB industry’s regulatory framework has largely been set. The focus has now shifted to the implementation phases that will take place over the next few years—and the new opportunities that may emerge. The next big impact will come from the accelerating push toward more exchange-traded and agency-like models.

On the one hand, cash over-the-counter (OTC) products are continuing to evolve in the direction of listed exchange models. More volumes and bigger tickets are moving through electronic channels (around 70 percent, 50 percent, and 20 percent of total volumes for FX spot, government bonds, and corporate bonds, respectively), and multidealer platforms are gaining ground in consolidating market liquidity. As a result, a number of players are reviewing the viability of single-dealer platforms in their current forms, particularly with regard to products for which banks do not need to provide extra liquidity to the market. In addition, both regulators and clients are pushing for greater transparency on the elements that make up the total “cost of trade,” as well as for more fee-based models.

On the other hand, we see OTC derivatives products developing in three phases:

- Phase 1. Regulators have already imposed central clearing of some OTC products in the U.S. and Europe. The true costs are still emerging, because the costs of collateral and post-trade servicing are masked by quantitative-easing subsidies as well as by banks that are pricing for market share rather than for profit.

- Phase 2. Regulators have started to restrict trading of some OTC products to regulated, more transparent trading venues. This began at the end of 2013 with swap execution facilities (SEFs) for interest rate swaps and credit default swaps in the U.S. The next wave will encompass more products and will expand to Europe with organized trading facilities (OTFs). To date, these developments have not opened up the game, as pre-SEF interdealer brokers have maintained their market share in the SEF environment. Most of the volumes remain on a request-for-quote (RFQ) model, with a few nonbank financial institutions directly accessing liquidity on dealer-to-client (D2C) venues. In the long run, SEFs will force more transparency and accelerate electronification. As a result, they are likely to increase pressure on execution margins.

- Phase 3. Some OTC products, particularly the most liquid and standardized, will move toward an agency-like model. Clients will partly shift to cheaper and less-tailored listed products—the so-called futurization of the market—although a sizable market will remain in OTC products for liability-matching purposes (particularly where hedge accounting is a necessity) and to mitigate the lack of liquidity. As SEFs develop and nonstandard OTC products become standardized, the most-liquid and shortest-tenor instruments may be directed to a central limit order book (CLOB).

Although much uncertainty remains about regulatory evolution, we believe that the regulatory climate will have a medium-term impact on banks’ strategic positioning along the value chain, as well as on both the CMIB revenue model and the operating model.

For both cash and derivatives products, tensions will rise around the value added by trading compared with sales, as more volumes go to electronic multilateral venues. For derivatives products in particular, clearing and collateral management have become part of the client value proposition, with a heavy emphasis on execution. While buy-side clients have already chosen their primary and secondary listed clearers to handle their OTC products, most of them have added executing brokers—on the basis of strong credit ratings and service models—that offer clearing nearly free of charge. In phases 2 and 3, we expect this trend to weaken (although not disappear) as a result of the following:

- The standardization of products

- The evolution of the competitive landscape, especially with European banks reducing their capital commitments to the U.S. (and the number of clients they can clear for), accompanied by a small number of new entrants from North America

- Emerging clarity on the true costs of clearing following full implementation of Basel III and the EU Capital Requirements Directive (CRD) IV, plus the tapering of quantitative easing

The revenue model will evolve slowly for derivatives. We expect revenues from execution to decrease as more volumes are traded electronically on SEFs, and as some volumes shift to lower-margin listed products. In parallel, while clearing and collateral-management revenues account for less than 10 percent of total revenues today, they may account for a much higher percentage in the future as collateralization gradually takes hold. We also expect to see some fresh revenue opportunities with new customized listed products (such as long-dated interest-rate futures), as well as further innovation in the netting of listed versus OTC products through central counterparty clearinghouses.

Finally, the operating model will be affected. As we see more listed and cleared products—and further fragmentation of liquidity, capital, and relationships—there will be a greater need for standardized and shared platforms for pre- and post-trade messaging, regulatory reporting, reconciliation, clearing, settlement, and payments. We expect third-party vendors to aggressively try to benefit from this situation and, where relevant, to build consortia and utilities for the industry.

Impact on the Six Core Business Models

In Global Capital Markets 2013: Survival of the Fittest, we highlighted six business models that we believe to be the most advantaged in the “new new normal” environment. While we still view these models as winning strategies, they all face challenges. Institutions embracing any of these models will need to reconfirm their value proposition and sharpen their competitive edge.

Powerhouses. These are the largest capital-markets players, with dominant share in one or more asset classes. Most of the powerhouses in today’s CMIB landscape are universal banks. Yet many are not capturing all of the synergies that they have access to. As more value shifts away from execution toward clearing and collateral management, differentiation among powerhouses will stem more and more from the ability to manage synergies with adjacent businesses (such as asset servicing and payments). There are also significant balance-sheet synergies to be captured, although some will be applicable only if ring-fencing regulations do not come into full effect.

Powerhouses must continue to actively prune their long tail of unprofitable clients. They should avoid the old habit of trying to be everything to everyone, and focus instead on product areas in which they can achieve true, scale-based competitive advantage.

Haute Couture Institutions. These players focus on creating sophisticated products for entities such as hedge funds, private banks, and sovereign wealth funds. They are likely to benefit from the return of a niche need for highly structured, high-margin derivatives, where they have a clear advantage. Further, we are seeing more demand for cross-asset and liability-driven investment strategies from yield-seeking investors. For example, collateralized-loan-obligation volumes are picking up again. But these institutions will also have to live with higher capital requirements and greater volatility in client demand. And they are likely to be continuously challenged in traditional products, where they cannot compete with powerhouses on efficient clearing and collateral management.

Overall, the competitive advantage for haute couture players is shifting from sheer product innovation to end-to-end, time-to-market excellence (such as process efficiency for new-product approval, and the agility of IT platforms). Human resources excellence will be critical both for attracting first-rate talent and for embedding the appropriate culture and “spirit of the law” that should help institutions navigate in the new environment.

Relationship Experts. These institutions, typically Tier 2 and Tier 3 players, leverage proximity and customized knowledge to build deep, long-term ties with their clients. Most relationship experts have been retrenching, yet also showing their resilience. Indeed, the CMIB business has proven to be very important to other business lines (such as corporate and private banking). Partnerships (both commercial and those involving the operating model) may prove crucial for relationship experts in order to secure client relationships that require global coverage, as well as to build a broad product offering and to gain scale and realize cost benefits.

Relationship experts continue to be challenged on client centricity, because the competition for client share is high. They will need to maintain investments in client-related IT, analytics, and big data to ensure that the service gap relative to powerhouses—all of which are Tier 1 players and have a natural advantage in this domain—does not become too large. Furthermore, it is of paramount importance that relationship experts place the bulk of their effort on those clients with which they can win significant share—particularly corporates, SMEs (small and medium-size enterprises), and small or regional financial institutions.

Advisory Specialists. These players provide premium advice to their clients’ top-management teams, particularly in M&A and capital structuring. The value of advisory specialists is clearly being questioned by some of the larger CMIB clients, a development illustrated by shrinking volumes at traditional, full-service advisories. With more deals being stock transactions—and with many corporates having strong cash positions—we expect volume to shift further toward niche advisory players. Looking ahead, we expect more commoditization of M&A execution (some of it being taken over by corporates), lower value added in DCM distribution (with many issues oversubscribed by investors), and little innovation in ECM structures. To remain competitive, advisory specialists need to attract and retain a few rainmakers capable of originating large deals. They also need to nurture their global networks.

Hedge Funds. The focus of hedge funds will continue to be on generating superior alpha, particularly over long time horizons. The extent to which they will be affected by further regulation remains unclear. So far, they have been less affected than the sell side, especially by measures that address compensation and capital. However, ring-fencing in the UK, for example, would lower a hedge fund’s access to leverage. Proposed European regulations would increase deal transparency, introduce capital requirements, and place limits on the types of investors that can invest in hedge funds.

Nonetheless, we expect hedge funds to remain advantaged compared with sell-side players. Furthermore, as more products become listed and cleared and as liquidity improves, hedge funds can fill some of the gaps left by sell-side entities.

Utility Providers. These players concentrate mainly on insourcing from investment banks and providing IT, operational, and (potentially) accounting solutions. Utility providers are slowly emerging not as outgrowths of consortia of banks but as neutral third-party vendors, clearinghouses, and other entities. They are still challenged by banks in their capacity to significantly reduce costs by means of labor-cost arbitrage, offshoring, improving operational excellence, and sharing change-the-bank costs. Many investment banks feel that using utility providers forces them to give away too much control and flexibility—with limited financial benefit, especially given the long-term uncertainties of such arrangements. To date, any substantial use of third-party vendors remains limited to Tier 2 and Tier 3 banks, although some Tier 1 players have engaged vendors on specific low-value-added activities.

With the perspective of the five years since the financial crisis first began to subside, a key question presents itself: To what extent has the CMIB industry truly recovered? Ultimately, the CMIB industry finds itself in a strategic deadlock of overcapacity and flat (or falling) revenues. Similar situations in other industries have sometimes been overcome through mergers, but regulation will likely prevent such a solution in CMIB.

As we said in Global Capital Markets 2013: Survival of the Fittest, each institution must choose its own path on the basis of its legacy, its particular strengths and weaknesses, and its aspirations. Within each choice of business model, there are tall challenges—but also great opportunities for the most adept players. There will be winners and losers. Successful institutions will be those that focus on revenue growth and market share. To win in these areas requires special emphasis on three domains: clients, people, and partnerships.

In our view, although banks clearly need to pursue additional cost reduction and manage the implementation of the regulatory agenda, it is time to put revenue growth at the top of the priority list. Achieving meaningful revenue growth will require increasing market share by The Push for Client Centricity at Investment Banks, building stronger client-related analytics, tapping opportunities from adjacent businesses, The Battle for Talent: Can Investment Banks Win?, and The Right Partnerships Can Help Investment Banks.

At this juncture, those institutions that make the right choices in critical areas can achieve ROEs of up to 15 percent between now and 2020, while others will struggle to cover their cost of equity—even in good years.

Acknowledgments

Within The Boston Consulting Group, for their valuable contributions to the conception and development of this report, our special thanks go to the core team of Eduardo Crespo and Mandeep Soor. In addition, Joe Cassidy, a senior advisor to BCG, provided valuable insights and assistance.

We would also like to thank the following members of Expand Research: Michael Aldridge, Rupert Bull, John Doonan, Raza Hussain, Damian McCarthy, and Franck Vialaron.

Finally, grateful thanks go to Philip Crawford for his editorial direction, as well as to other members of the editorial and production team, including Katherine Andrews, Gary Callahan, Kim Friedman, Abby Garland, Gina Goldstein, Sara Strassenreiter, and Janice Willett.