Over the past couple of decades, corporate venture capital (CVC) investing has been characterized by its boom-and-bust cycles: companies would increase their investments during frothy markets to boost financial performance and then pull back during economic downturns when the prospect of quick financial gains evaporated.

Today, corporate venturing is taking a much different

CVC’s Global Role Is on the Rise

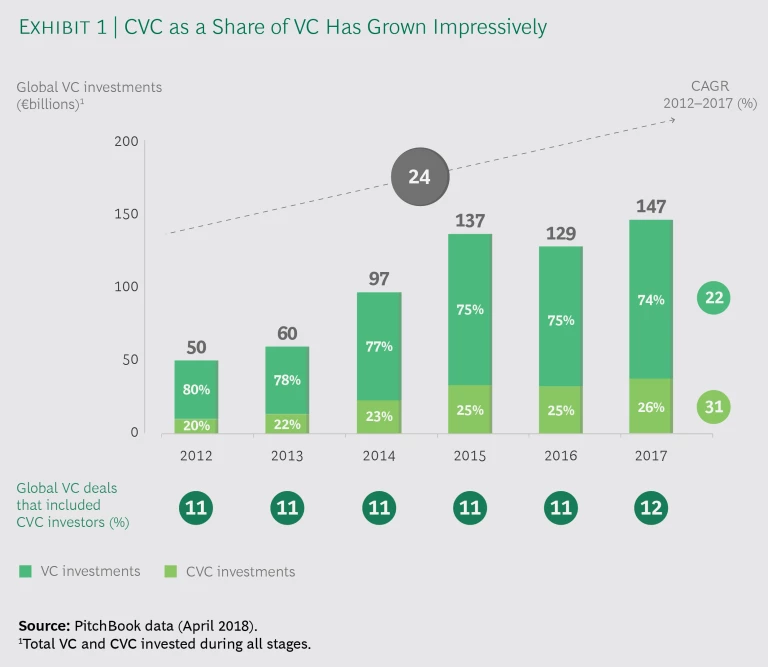

CVC’s rising importance may not be immediately evident if one looks at the percentage of global VC deals that included CVC investors. That number remained relatively steady, at 11%, from 2012 through 2016 and rose to only 12% in 2017. However, the percentage of CVC investments as a share of global VC investments grew from 20% in 2012 to 26% in 2017 as total global VC investments increased from €50 billion to €147 billion. That gives CVC investments an impressive compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 31%. (See Exhibit 1.)

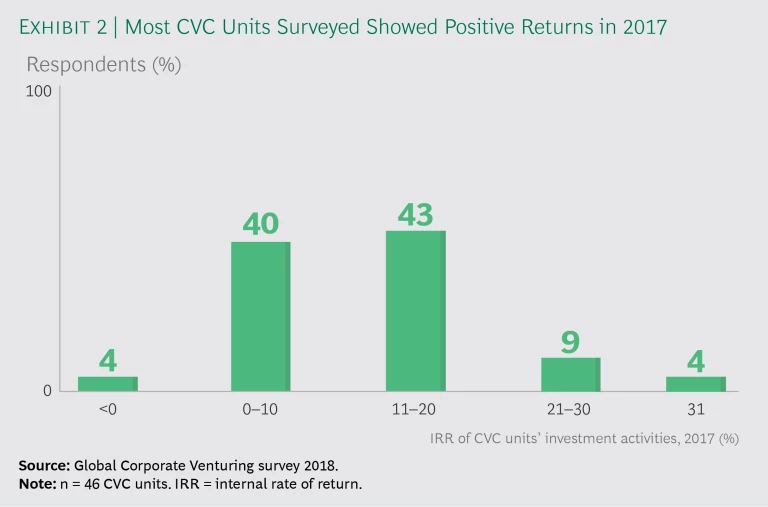

Fortunately, that stepped-up investment coincided with strong VC returns in all major markets. Returns in Asia led the way, with 22.9% over the past 5 years and 16% over the past 15 years. US returns came in second, with 13.7% over the past 5 years and 7.4% over the past 15 years. Europe’s returns trailed US returns but were still strong: 11.2% and 5.4%, respectively. CVC performance mirrored this overall VC success. More than 95% of CVC units reported positive returns in 2017. (See Exhibit 2.)

It’s worth noting that the five-year performance of VC returns was helped by the high valuations of so-called unicorns (startups valued at more than $1 billion) and an active acquisition environment. The value of corporate acquisitions of venture-backed startups grew from €43 billion in 2012 to €75 billion in 2017. This represents a CAGR of 12% even though the value of acquisitions leveled off during 2016 and fell in 2017.

As companies’ expectations for and funding of CVC investments have grown, so, too, have the stakes. To be successful, companies must further develop their CVC capabilities.

Leading Companies Apply Best Practices

The wind has been at the backs of CVC investments, but their strong performance is also due to companies getting better at this type of investing. Leading companies apply and redefine the following best practices:

- Set a clear objective. To start, a company must decide if the principal objective of its CVC unit is financial or strategic. This decision guides the optimal organization structure, incentive scheme, and people mix.

- Define search fields. A company must also determine where its CVC unit should look to find potential investments. Search fields serve as guardrails for the CVC unit, ensuring that prospective investments are relevant to the business, which in turn keeps senior managers engaged and supportive.

- Select a leader from outside. A company should tap an experienced outsider to lead its CVC organization—someone who is connected to the right networks and has access to the best technical expertise.

- Hire the right mix of talent. Staffing a CVC organization with talent from inside and outside the company is ideal. Internal talent can create a bridge between the unit and the company’s business units and facilitate good working relationships; external talent can provide access to new networks as well as contribute valuation and contract expertise.

- Ensure independence. A CVC unit should be separate—physically and operationally—from the company’s daily activities to give the unit room for innovative, disruptive thinking and activities.

- Foster collaboration with the business units. A CVC unit needs autonomy, but it may also need to draw on the company’s expertise or other resources—and it should be encouraged to do so. The unit should not be walled off from the company.

- Enable lean, agile, and relevant governance. A company should put lean and agile decision-making processes in place so its CVC unit can keep pace with startups. And by including key stakeholders from business units in the decision-making process, companies can ensure support from senior managers.

- Ensure consistent financing. It’s imperative for a company to fund its CVC unit consistently throughout economic cycles—the downturns as well as the upturns—in order to retain talent and maintain credibility in the VC market.

Three Ways to Improve the Impact of Corporate Venturing

Corporate venturing has matured significantly over the past five years, but there is still much room for improvement. Many companies find that too few investments eventually lead to revenue-generating businesses for the corporate parent. And many companies that have given their CVC unit a strategic mandate don’t do a good job of coordinating the unit with other in-house innovation activities, such as R&D and incubation. Companies can tackle these issues by scaling startups faster and evaluating potential acquisitions, as well as by integrating corporate venturing into the corporate framework. Companies can also benefit by using venturing activities to accelerate their digital transformation.

Scaling Startups Faster and Evaluating Potential Acquisitions

Despite the strong returns of recent CVC investments, some senior leaders question their value—or even lose interest in them—because they rarely deliver meaningful top-line revenue or profits.

CVC units can address leaders’ concerns in two ways. First, CVC units can partner with startups to scale their businesses faster and potentially make future acquisitions of the scaled businesses. Second, CVC units can improve the way they identify more immediate acquisition targets for the corporate parent. Whether pursued separately or together, these actions can enable CVC units’ investments to deliver measurable top-line growth and profits.

CVC units will find that taking these actions can address startups’ concerns as well. Given the amount of VC that’s available, getting funded often isn’t startups’ biggest challenge. What startups often need—and what can set an investor apart—are the capabilities to scale the business fast. A CVC unit with access to a wide variety of expertise and resources has a clear advantage over traditional VC firms.

What startups often need—and what can set an investor apart—are the capabilities to scale the business fast.

BCG and Hello Tomorrow surveyed more than 400 deep-technology startups, inquiring about their needs and their preferred partners. Of the possible alliances, respondents preferred partnering with corporations to gain market access (43%), technical knowledge and expertise (26%), and business knowledge and expertise (19%). (See “What Deep-Tech Startups Want from Corporate Partners,” BCG article, April 2017.)

As a partner, it’s critically important for a company to avoid hindering the startup’s agility or crushing its creative spirit. Coca-Cola avoided this trap when it invested in, and subsequently acquired, Honest Tea.

In 2008, Coca-Cola acquired a 40% stake in the organic tea company, which was established in 1998. Despite a crowded market, Coca-Cola’s venturing and emerging-brands unit, which comprises the company’s corporate venturing and incubation functions, leveraged its distribution network and scaled Honest Tea’s business from $38 million to $75 million in three years.

That success led Coca-Cola to buy Honest Tea outright in 2011, and by 2015, revenues had more than doubled, to $180 million. Today, Honest Tea’s products can be found in more than 100,000 stores across the US.

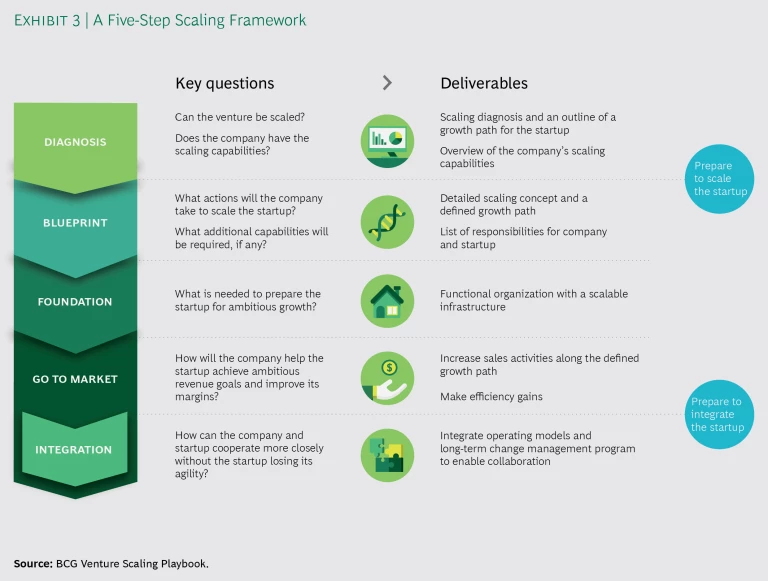

The takeaway: Scaling a startup can lead to an acquisition that delivers for the corporate parent. To help companies assess potential startup partnerships and scale a business, we created a five-step scaling framework. (See Exhibit 3.) CVC units can also use it to assess the scaling potential of companies that are already in their investment portfolio.

Scaling a startup can lead to an acquisition that delivers for the corporate parent.

But even if scaling a startup doesn’t lead to an acquisition, a CVC unit can glean insights into a startup’s industry segment, the players, its business model, and the technologies it uses or develops. Such insights can help CVC units not only identify acquisition targets but also assess them, reducing investment risk.

Another way CVC units can improve the way they identify acquisition targets is by working closely with the company’s business units to understand their technology and business needs and to exchange perspectives on potential acquisitions. Business units, with a strong command of their own industry’s dynamics, can alert CVC units to smaller targets that might otherwise be overlooked.

The bottom line is that, by partnering closely with startups and business units, CVC units can maintain the interest and support of senior leaders.

Integrating Corporate Venturing into the Corporate Framework

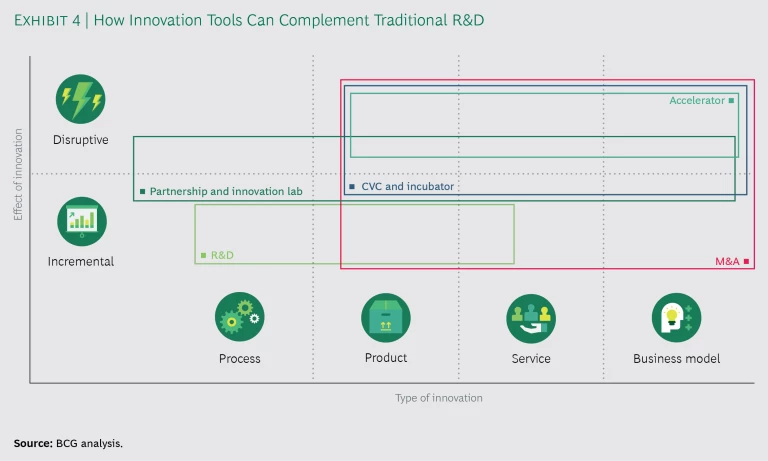

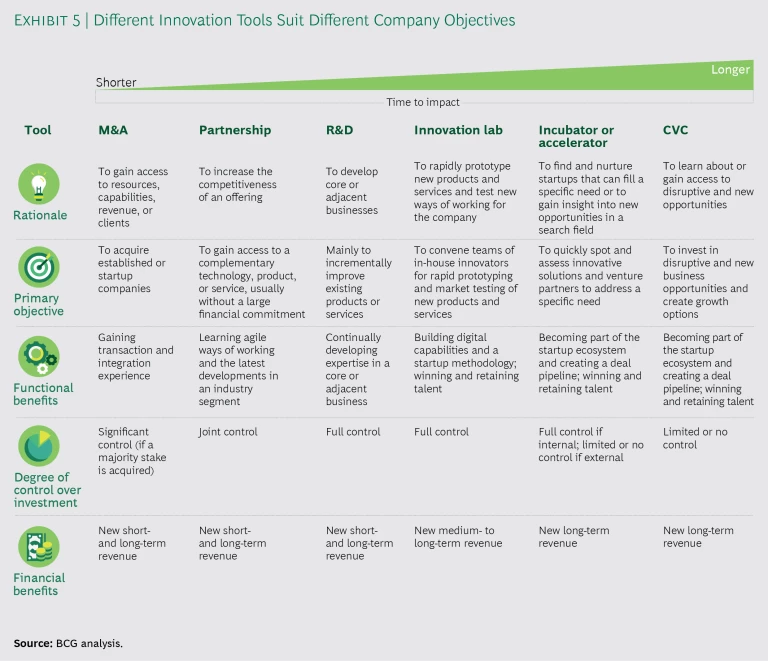

CVC is not the only innovation tool that companies can use to complement internal R&D. Rather, it is one of several; companies choose which tools to use depending on their innovation strategies or specific innovation goals.

CVC investing is increasingly popular, though. BCG’s research has found that 40% of the 30 largest companies (as measured by market capitalization) in each of seven innovation-intensive industries were actively engaged in CVC investing in 2015, up from 27% in 2010. (See Corporate Venturing Shifts Gears, BCG Focus, April 2016.)

Unfortunately, corporate venturing often occurs outside the established corporate framework. When that happens, R&D and other functions often perceive the effort—whether CVC investing, incubation, or another endeavor—to be a pet project (of the CEO or another senior leader) that’s competing with R&D efforts, not complementing them.

Corporate venturing needs to be part of an overall corporate innovation approach.

To be most effective, corporate venturing needs to be part of an overall corporate innovation approach that clarifies how innovation tools complement the traditional R&D function. (See Exhibit 4.) Each tool is geared toward one or more of the various types of innovation (process, product, service, and business model) and for different effects (either disruptive or incremental) and can accelerate innovation faster than traditional corporate R&D.

The corporate innovation approach also needs to clarify how to use the tools to achieve the company’s innovation goals. (See Exhibit 5.) For example, if an organization wants to learn about disruptive or new opportunities, CVC is a good tool. But if it wants to quickly tap into a new revenue source, then M&A expertise is needed to acquire a controlling stake in the business. Or, if a company is looking for future revenue, an incubator is an excellent tool, given enough time: in most instances, it takes a newly incubated business about six to eight years before measurable revenue or profit is realized. An organization must also clarify when a combination of tools will best address specific innovation challenges.

Successfully integrating corporate venturing into the corporate framework requires considering if the goal is disruptive or incremental innovation in processes, products, services, or business model. To enable disruptive innovation, the organization structure needs to put distance between innovation development and the core business, particularly where vested interests might slow progress.

Corporate venturing also needs to be hardwired into the capital allocation process. Temporary innovation initiatives can always be funded on top of existing R&D budgets; however, companies also need to think long term about how to allocate capital among R&D and more disruptive innovation tools. To ensure that R&D and venturing tools complement one another, companies have to give R&D access to the innovation vehicles or even reward R&D departments for leveraging these vehicles to achieve clearly defined innovation objectives.

Even with adequate funding, however, corporate venturing won’t live up to its potential unless there’s a free flow of information between the business units and the CVC unit for agile decision making. Some companies may favor an informal approach, such as creating a communications hub that brings various parts of the organization together to discuss innovation and new technologies on an ongoing, fluid basis. (See “Tencent’s Use of Innovation Vehicles.”) Other companies may prefer a more formal approach, such as creating an innovation board to define the scope of each innovation effort, coordinate the work, exchange lessons learned, monitor and steer performance, allocate capital, and make project-termination decisions. But every company needs to find an approach—formal, informal, or something in between—that is best for its culture.

TENCENT’S USE OF INNOVATION VEHICLES

TENCENT’S USE OF INNOVATION VEHICLES

Tencent, a global provider of internet-related services and products, telecom services, and technology, has three innovation goals: to build up the ecosystems around social network platforms WeChat and Qzone by acquiring additional content, such as videos and games; to help every company become an internet company by giving businesses in various industries access to Tencent’s customers; and to support regional expansion in Asia. To achieve its goals, Tencent is making use of several innovation vehicles. Along with its well-established R&D effort, the company leverages CVC and M&A investments, incubators, and innovation labs:

- CVC and M&A Investments. Tencent has a single investment team that is responsible for making both CVC (minority) and M&A (majority) investments. After acquiring a company—particularly a small, creative business, such as a gaming company—Tencent is careful not to stifle innovation by demanding close integration.

- Incubators. In exchange for an equity stake of 5% to 10%, startups are allowed to access Tencent’s internet platform from more than 20 locations in China. In turn, Tencent’s mobile internet group uses these startups to test ideas when it lacks in-house knowledge. If a startup reaches sufficient scale, the company considers making a more substantial CVC investment.

- Innovation Labs. At its Shenzhen headquarters, Tencent has an artificial intelligence lab with 250 employees who work on innovations in the areas of machine learning, computer vision, speech recognition, and natural language processing.

It takes a deliberate communications strategy to coordinate the innovation vehicles. Tencent’s has informal and formal elements. On the informal side, the company uses WeChat as a communications hub so business and investment teams can exchange ideas continually. Allowing information to flow easily enables innovation and deal-making ideas to emerge from the business side, which might identify a missing technology, or from the investment team, which might be exploring fields where Tencent has no presence. However, the company’s communications approach also has formal elements. For example, during quarterly offsite gatherings, the CVC team defines business priorities and new vertical markets to target.

Daimler, for example, is using multiple innovation vehicles—CVC, an incubator, an accelerator, and partnerships—to tap into the startup world and become a leading mobility provider.

The company combined its CVC and M&A units to create M&A Tech Invest. It has made several acquisitions, including mytaxi, a taxi-ordering app that serves more than 40 cities worldwide, 30 of which are in Germany. M&A Tech Invest also has made several investments in startups, including FlixBus and Blacklane. In addition, Daimler has an incubator and innovation lab called Lab1886. It gives internal employees the opportunity to pursue disruptive ideas using a stage-gate process—ideation, incubation, and commercialization—across its global network, which includes offices in Beijing, Berlin, Stuttgart, and Sunnyvale, CA.

The company has funded an accelerator called Startup Autobahn. It is powered by Plug and Play and provides external startups with infrastructure, capital, and access to a global partner network. The accelerator’s purpose is to assess and further develop startups’ ideas in order to enter into joint projects with Daimler’s corporate partners in the areas of mobility, production, and related topics. Additionally, Daimler is constantly on the lookout for ideas for its Startup Intelligence Center, which is the central entry point for innovative startups that are seeking to partner and collaborate with Daimler Financial Services’ ventures in mobility (such as car2go), fintech, and insurtech.

Daimler is well aware that some cultural change is necessary to embrace all these innovation vehicles. To this end, DigitalLife@Daimler drives cultural change in the company’s core business to encourage employees to adopt startups’ ways of working (such as using digital processes). DigitalLife@Daimler also sponsors activities, including employee networking (via a new social media platform), yearly digital events (such as DigitalLife Day), and opportunities to contribute to or scout for ideas through DigitalLife Innovation Camps and Crowd Ideas Platform.

Using Venturing Activities to Accelerate a Digital Transformation

Capitalizing on a corporate venturing unit’s startup partnerships to accelerate a digital transformation is a frontier that few companies have yet attempted to cross, but it is one they should explore. A successful digital transformation requires employees to develop new skills, understand digital technologies, and learn new ways to work and make decisions. It also requires organizations to attract and develop digital talent. Tapping into startups’ know-how in these areas can help a company accelerate its transformation and get more bang for its corporate venturing buck. (See “Digital Maturity Is Paying Off,” BCG article, June 2018.)

Developing New Skill Sets. What skills does a startup have? What skills does a business unit need? And who should be trained? CVC units are already working with both startups and business units, so they are in the best position to assess the potential fit between a startup and a business unit and then connect and coordinate the respective parties to facilitate a two-way exchange of information and skills. For example, GE has a fellowship program that places GE employees in startups for specific projects; the employees learn lean and agile methods that they can bring back to the organization.

Learning New Technologies and Ways of Working. Corporate venturing units often fund incubators that offer corporate resources and mentoring to early-stage startups. Because these startups need help in a wide variety of areas, incubators can expose a critical mass of internal talent to digital technologies and lean and agile ways of working and decision making. The more employees learn, the more they can facilitate a digital transformation. CVC units that aren’t working with an internal incubator should consider starting one or use another innovation vehicle, such as an accelerator or innovation lab. (See “An Incubator Primer.”)

AN INCUBATOR PRIMER

AN INCUBATOR PRIMER

Among innovation tools, incubators are particularly well suited for disruptive innovation. But to set an incubator on a firm foundation, companies should take several important steps and set expectations appropriately:

- Create a legal subsidiary quickly. When setting up an incubator, companies should not wait until the eleventh hour to create the legal subsidiary, a process that often takes much longer than anticipated and can delay the testing of crucial new technologies in fast-moving markets. (For example, it may not even be legally feasible to test or launch the incubator’s website before the legal subsidiary is created.)

- Pick the right CEO. Companies can choose an incubator CEO from inside or outside the company. Insiders often perform better when there is a strong sales focus; outsiders often perform better when specific technology or product expertise is required.

- Think long term. Mentoring a startup usually takes six to eight years—longer than the tenure of many corporate CEOs. Companies need to protect the incubator from shifting priorities by making a long-term commitment to supporting the innovation and growth strategy. Organizations also should secure buy-in from the business units so that if a key person leaves, the incubator still has the unit’s support.

- Prioritize growth over profits. Companies should refrain from putting pressure on startups to generate profits too soon. Most startups should focus on growth—rather than high margins—to achieve scale and build a leading market position.

- Keep compliance basic. Large companies should avoid extending all their compliance rules to startups. Although compliance is important for startups, management boards should waive rules where possible—such as for purchasing and recruiting—to keep the startups agile.

- Ensure support from top managers. Senior leaders aren’t typically involved in an incubator’s day-to-day operations. But at certain times—to obtain exceptions from standard compliance rules, for example, or to access specific corporate resources—senior leaders’ support will be essential.

Recruiting and Developing Digital Talent. People with digital skills often are uninterested in working in a traditional corporate culture because of slow decision making, strict processes, and limited willingness to change or disrupt the status quo. This can make it difficult to recruit and train employees to help drive the digital transformation. But by working with startups, companies can learn first hand what attracts this kind of talent and how to develop it, particularly with regard to how working conditions, culture, and incentives all come into play. Companies can then make adjustments and tailor their recruitment to build a workforce with the right skills for a rapidly changing future.

Until relatively recently, corporate venturing was a fringe activity often abandoned during economic downturns. But it’s now well established, generating impressive investment returns over the past five years. Moreover, it’s proving a critical way to tap into the kind of innovative thinking necessary to keep up with the rapid changes in the marketplace, particularly those associated with digital transformation. Even so, some CEOs and other senior leaders question the business relevance of corporate venturing, since these investments are usually in startups that don’t contribute meaningfully to top- and bottom-line growth.

CVC units need to begin to prove their business relevance by partnering more closely with startups to scale them faster and by improving the way they identify M&A targets. It’s critical for CVC units to make the business case for corporate venturing forcefully and successfully. The future will belong to those who integrate corporate venturing into a broad innovation approach to drive growth and digital transformation.