Middle Eastern ports have enjoyed success by building high-quality infrastructure to serve the large cargo volumes flowing through the region. To maintain the momentum, it is now time for port stakeholders to step back and reflect more strategically about their next moves.

Although the Middle East accounts for less than 3% of global GDP, its ports handle approximately 20% of global seaborne trade. This disproportionate share is the result of both geographic advantages and well-executed investments. The ports are located at the intersection of several trade routes and serve as hubs for other ports in the region and beyond. In the years since the global financial crisis, Middle Eastern ports have invested in building capacity to handle cargo flows on the Far East–Europe trade route (the world’s busiest or second busiest route for many cargo types), as well as on smaller routes. Large ports, in particular, have developed infrastructure that is impressive for both its scale and the technology deployed. Several port groups have developed into organizations respected in the region and globally, with the ability to compete against the world’s best.

But as is often the case following a period of strong growth, there are causes for concern. Overcapacity, exposure to transshipment, and lagging port productivity threaten to slow or even reverse the upward trajectory of the region’s ports.

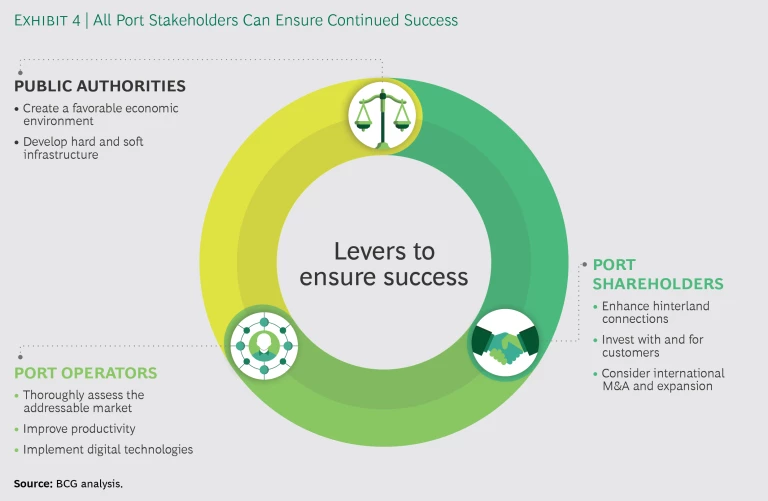

Through our work supporting ports in the Middle East and globally, we have identified a number of strategic priorities and levers that can help port stakeholders sustain strong performance. Port shareholders should focus their investments on developing hinterland connections rather than on building more capacity. Port operators should seek to capture more business from existing and potential customers and pursue productivity improvements and digitization. Public authorities should continue their efforts to create a favorable business environment for ports and promote industrial development for the benefit of national and regional economies.

Strong Growth but Threats Are Looming

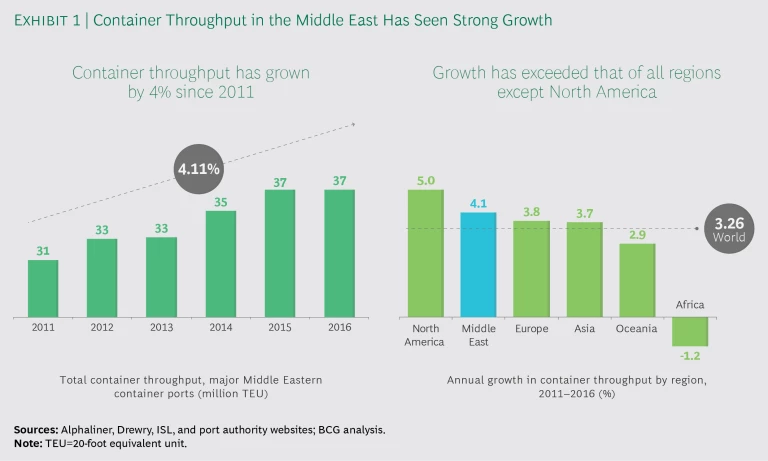

For many Middle Eastern ports, the region’s favorable economic climate since the global financial crisis has helped fuel good performance in terms of both volume served and financial returns. From 2011 through 2016, the compound annual growth rate of container throughput was 4%, which exceeded the global average. (See Exhibit 1.) The throughput growth rates of other types of seaborne cargo have also been impressive. But Middle Eastern ports face three looming threats to their continued success.

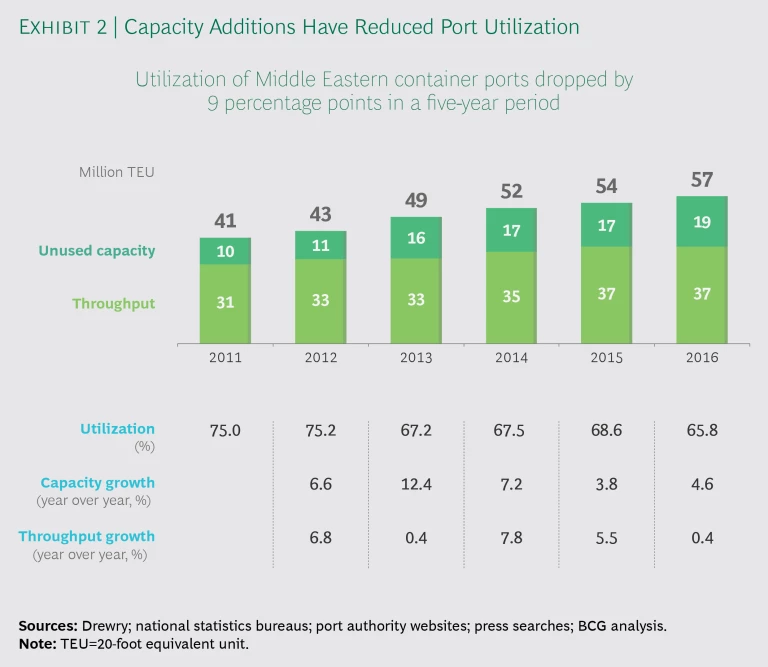

Rising Overcapacity. Middle Eastern ports have aggressively added capacity. From 2011 through 2016, container capacity increased by 16 million 20-foot equivalent units (TEU). This represented an annual growth rate of approximately 7%, versus 4% for container throughput. The additional capacity caused utilization at ports to fall by 9 percentage points, from 75% to 66%. (See Exhibit 2.) This utilization rate is generally considered low and puts downward pressure on handling rates. In some locations, the level of overcapacity is severe. Unless growth accelerates significantly, it does not appear that additional capacity will be required for the foreseeable future. Ultimately, the overcapacity will lead to a lower return on capital than is normally expected from port infrastructure investments.

Despite already low utilization, Middle Eastern ports show no signs of holding back on further investments in capacity. Ports have announced plans to add capacity totaling approximately 57 million TEU by 2030, thereby doubling the current level. By 2022 alone, assuming the recent throughput growth continues, the new capacity will drive down utilization by more than 8 percentage points, to approximately 57%. It is unlikely that ports will build all the announced additions. They may reassess their plans if expected volumes fail to materialize or if they lack the financing necessary to build the full amount announced. Even so, the proposed additions are staggering to consider.

High Exposure to Transshipment. Transshipment accounts for more than half (53%) of the throughput of Middle Eastern ports. At ports in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Oman, transshipment represents the lion’s share of utilization. A large volume of the transshipped cargo is destined for ports in other countries within the region and outside the region.

To end their dependence on transshipment hubs, smaller destination ports (which serve as import-export gateways for their own hinterlands) are improving infrastructure, hiring experienced port operators, and encouraging shipping lines to make direct calls. They also aspire to handle more transshipment cargo. This year has seen several high-profile examples of destination ports taking such steps to counter the dominance of transshipment hubs. Destination ports may also benefit from regulatory changes that enable them to receive direct cargo flows, thereby reducing their dependence on transshipment hubs.

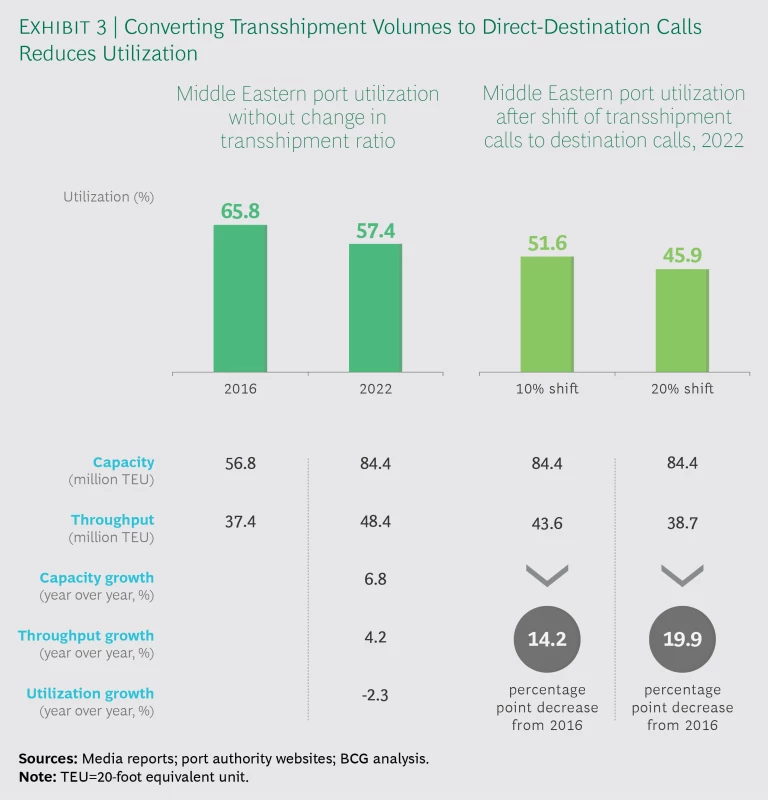

If smaller destination ports succeed in attracting large volumes of direct calls, the current model of serving the entire region with a few transshipment hubs will be threatened. Even at constant levels of trade, overall utilization will fall sharply. To calculate throughput, transshipped containers are counted multiple times (because they are loaded off of ocean carriers and then loaded onto smaller vessels for discharge at destination ports). Decreasing transshipment volume would eliminate many of these transfers. Considering the steps already taken by the region’s destination ports, we estimate that 10% to 20% of transshipment volumes could become direct-destination volumes by 2022. If such a shift occurred, the overall utilization of Middle Eastern ports would be approximately 14 to 20 percentage points lower than in 2016. (See Exhibit 3.)

Lagging Port Productivity. Empirical evidence suggests that, except for the most successful and established players, productivity is lagging at a number of Middle Eastern ports. This is not unexpected given that many of the newest players are still at an early stage of development. Because these ports have been busy bringing new capacity online, commissioning larger cranes, and installing new operating systems, they have not focused on improving productivity. The region’s relatively low unit costs for labor have made cost optimization less of a priority than in other locations.

Each Stakeholder Has a Role to Play

To provide a framework for exploring the actions required to avert these threats, we differentiate among three types of stakeholder:

- Port shareholders are owners responsible for investment decisions relating to port facilities and hinterland connections.

- Port operators manage day-to-day terminal operations and are responsible for commercial performance.

- Public authorities are government entities that pursue economic-development objectives to promote prosperity.

In the Middle East, the distinctions among these roles can be blurry. For example, public authorities are often shareholders of both ports and port operators. But the distinctions are still valuable when considering the types of moves that will maintain momentum. (See Exhibit 4.)

Port Shareholders

In the context of deteriorating utilization, port shareholders should be cautious about investing in additional capacity. No investment plan for new capacity should be approved unless it identifies the specific volumes to be served. To avoid a zero-sum game of retaliatory moves, port shareholders should refrain from investing in new capacity intended to capture volumes currently handled by nearby ports. Instead, they should seek to extend their port’s reach by investing in inland connections and facilities tailored to the customers they currently serve. Shareholders that have resources for further investments should consider diversifying through M&A or development projects outside the region.

To create additional capacity, port operators should favor productivity gains over capex.

Enhance inland connections. Shareholders can promote a higher volume of destination calls by investing to enhance connections between the port and inland business hubs and population centers. Improved inland connectivity—including logistics services, transportation, and warehousing—allows a port to extend its reach beyond the immediate area it serves and increase its participation in end-to-end cargo flows. For example, ports around the world are capturing greater value from their strategic locations by investing in rail and road transport services. One seaport has invested in upgrades to an existing railway network in order to better serve customers in neighboring landlocked countries. And in an example of innovation from the air freight industry, an airport has launched a road transport service to capture volumes from airports closer to the origin of individual cargos. The service includes package collection and inland consolidation, creating efficiencies for customers.

Although such inland connectivity solutions are generally regarded as having lower margins than port handling operations, they are worth considering on a case-by-case basis in the Middle East. The region’s interconnected national economies and short distances between ports and major inland markets create many such opportunities. For example, Saudi Arabia can be served from multiple gateways, ports in Jordan can serve Iraq, and ports in Oman can serve Yemen or the UAE through inland connections that obviate the need to sail through the Strait of Hormuz.

Invest for and with customers. By investing to support importers and exporters, port shareholders can solidify existing volumes and make it harder for large-volume customers to switch ports (creating “stickiness”). Examples include co-investing in the construction of roll-on/roll-off facilities for predelivery inspections of automobiles, or of distribution centers or temperature-controlled warehouses for food and beverage products. Given the prevalence of oil and gas companies in the region, ports should consider targeting related downstream industries, such as plastics and petrochemicals, through dedicated warehouses and container freight stations (where containers are packed and unpacked). Such facilities will be vital to retaining customers as competition increases among destination ports.

Consider international M&A and expansion. In general, investors should pursue local M&A opportunities, which offer many ways to create synergies. However, given that such opportunities are rare in the Middle East, port shareholders with an appetite for additional investments in the ports sector should consider diversifying through international M&A as well as expansion. The advantages include:

- Identifying new growth opportunities

- Entering regions whose stage of development is different from the Middle East’s

- Strengthening the organization resulting from a merger or an acquisition by creating a deeper bench of talent, with greater or different expertise

- Preparing for the future by investing in economies less dependent on oil

Port Operators

Port operators should gain an in-depth understanding of the end-to-end cargo flows served by their ports and how they can add value within these flows. To create additional capacity, they should favor productivity gains over capex, with an emphasis on deploying “smart port” technologies.

Thoroughly assess the addressable market. Port operators should seek to increase their share of wallet from the shippers they serve today, and they should target new business while avoiding head-to-head competition on handling rates. The best way to start is to conduct a thorough assessment of the end-to-end cargo flows served by the port, as well as the flows it could potentially serve in the future. (See Exhibit 5.) By gaining a deep understanding of the addressable market for additional business from their extended hinterland, operators can determine the winning strategy for their local context. This assessment is essential to developing a competitive, and possibly distinctive, value proposition for serving carriers and shippers.

Achieving such a detailed understanding of markets and customers is time consuming. It also requires a greater level of customer intimacy than port operators are necessarily accustomed to, having generally placed a greater emphasis on attracting and retaining ocean carriers. A thorough assessment of the addressable market covers a wide variety of topics:

By adopting smart technologies, Middle Eastern ports can, at limited cost, demonstrate global leadership to shipping lines.

- Current and Expected Trade Flows. The operator assesses the trade flows to and from its hinterland and its effective market share for those flows. It should understand which flows have the most promising outlook and how well it is positioned to capture them.

- Alternative Logistics Solutions for Serving Key Markets. It may be possible to serve major hinterland markets by many different routes. (See “A Case Study of Hinterland Logistics: The US Midwest.”) Riyadh, for example, can be served by ports located to the east, west, or south. Port operators are well positioned to assess the various logistical alternatives for serving their hinterlands. A detailed analysis should compare them in terms of time, cost, and reliability. The results of the analysis will enable the operator to identify how, and for which types of cargo, it could extend its reach to serve important business or population centers.

A CASE STUDY OF HINTERLAND LOGISTICS: THE US MIDWEST

A CASE STUDY OF HINTERLAND LOGISTICS: THE US MIDWEST

The US Midwest offers an analogy to landlocked regions in the Middle East. Seaborne cargo can reach the Midwest by a variety of routes:

- Transpacific service to California ports, with rail transportation to Midwestern destinations

- Transpacific service to Canadian ports, with rail transportation to Midwestern destinations

- Transpacific service to Gulf of Mexico ports (via the Panama Canal), with river or road transportation to Midwestern destinations

- Transatlantic service to large East Coast ports, with road or rail transportation to Midwestern destinations

Which routes will gain share is driven by multiple dynamic factors. For example, the emergence of large ships mostly deployed on Far East–Europe routes favors East Coast ports as the gateway to the Midwest. These routes have lower slot costs from, for example, Shanghai to Chicago, despite having a much longer sea-faring distance than a transpacific connection to California ports. Among the many other factors are the network organization of shipping lines, the availability of port capacity, transshipment regulations, the ease of customs procedures, the expansion and tariff structure of the Panama Canal, and other regulatory issues.

- Competitive Offerings. The operator identifies the other ports that serve its hinterlands and compares them with its own port in terms of landside access, seaside connectivity, services, and customer experience. It assesses its effective market share for selected cargo flows and its effective share of wallet with key exporters and importers.

- Buying Factors and Customer Pain Points. For selected large trade flows, it is essential to understand the roles of various stakeholders (exporters, importers, buyers, sellers, agents, and shipping lines) when deciding which route, shipping line, and port to use. In theory, exporters and importers are the decision makers. In practice, buyers or sellers may dictate the choice. Time pressure may also influence these decisions. Additionally, the operator assesses its current customers’ pain points, how best to address customer feedback, and the opportunities for shareholders to invest with and for customers to create stickiness. It should conduct a similar assessment of the pain points for its competitors’ customers. Interviews with key current and potential customers are critical to understanding the forces at play, the pain points, and what customers value most.

Port operators should use the assessment’s results to determine how their shareholders can invest wisely. After identifying the best investment opportunities, they can prepare a business case for shareholders to approve.

Improve productivity. Even in the context of ongoing growth and stable financial performance, port operators’ long-term success requires optimizing operational performance, reducing waste in key processes, and preserving resources. In the face of declining utilization, it is especially critical for port operators to favor productivity improvement initiatives over investments to add capacity. Our work around the world shows that productivity improvements can significantly and sustainably increase capacity. In a recent project at a global port operator, we found instances in which optimized processes could increase capacity by up to 20%. The returns on the modest investments required to raise productivity can greatly exceed those generated by the capex-heavy investments necessary to construct berths and terminals. Productivity improvements can also create capacity more quickly.

To decide which initiatives to pursue, port operators should analyze the bottlenecks that are decreasing port productivity. This analysis can serve as the basis for designing processes that improve key metrics, such as productivity per berth.

Implement digital technologies. Progressive ports around the world are embracing digital breakthroughs such as connected platforms, cloud-based services, mobile devices and apps, sensors, autonomous transportation, and big data solutions. Digital smart-port technologies make ports and their partners more productive and competitive by enhancing existing operations without major infrastructure upgrades. Because these solutions generally require low capex, they have short payback times. In contrast, traditional port automation systems often require very large investments, and they have not demonstrated the ability to raise productivity levels.

By adopting smart technologies, Middle Eastern ports can, at limited cost, capture these benefits and demonstrate global leadership to shipping lines. Ports should use a structured approach to selecting from among the many technological and digital investment opportunities. (See To Get Smart, Ports Go Digital, BCG Focus, March 2018.) Here are some examples of applications to consider:

- Predictive Maintenance for Cargo-Handling Equipment. By enabling ports to detect and address equipment problems before breakdowns occur, predictive maintenance improves equipment availability and promotes higher productivity. The foundations for predictive maintenance are data about the operating environment (such as temperature and stresses) and detailed machine log data about equipment operating conditions. Algorithms and machine learning use this data to build probabilistic models that inform preventive maintenance schedules.

- Scheduling and Tracking of Truck Movements in the Port Ecosystem. Ports located in congested urban areas need to help trucks accelerate their movement into and out of the terminal. One technology-powered solution is a terminal appointment system that lets trucking carriers reserve specific times for dropping off or picking up freight. By reducing the time that truckers spend clogging port arterial roads or sitting idle, appointment systems minimize turn times and improve air quality. We have seen such systems successfully deployed around the world. Additionally, ports in Asia and Europe are testing a GPS-based monitoring system for trucks. The system tracks truck movements, notifies terminals when vehicles are approaching facilities, and provides drivers with real-

time directions.

Public Authorities

By promoting a favorable business environment and industrial development, port authorities create benefits for ports over the long and short terms.

Industrialization projects undertaken by public authorities can significantly improve the business environment for nearby ports. The creation of new urban areas and large industrial developments may provide them with unique opportunities. Examples include large projects such as NEOM, a new city and economic zone planned for northwest Saudi Arabia that is expected to transform many sectors of the national economy. Additionally, smaller-scale industrial expansion projects are creating tangible, shorter-term opportunities. Examples include the Al Khabra phosphate mining and processing project for Ma’aden, the Saudi Arabian mining company; the expansion of the Emirates Aluminum train in the UAE; and the Liwa Plastics Industries Complex developed by Orpic, Oman’s national refining and petrochemicals company. These projects generate bulk import flows (such as for bauxite or feedstock) as well as container export flows (such as for ingots or plastics).

In addition to targeted industrial expansion projects, public authorities can promote employment and economic benefits by creating the right environment to attract light-manufacturing and logistics facilities in and around port areas. Examples include food-processing units, bottling plants, facilities for bagging bulk cargo, and facilities for import processing and predelivery inspection of new cars. Initiatives to attract such facilities are conceived as part of a wider economic development agenda and do not focus on promoting particular business interests. However, regardless of their broader objectives or even their size, some may generate substantial cargo volumes and port revenues.

The Middle East has many examples of the successful development of free zones or industrial parks. The largest and most successful is the well-known Jebel Ali Free Zone, which is home to more than 100 Fortune 500 companies. In pursuing new projects, public authorities should establish both hard infrastructure (such as well-maintained roads and telecommunications networks) and soft infrastructure (such as a hassle-free environment for doing business and effective customs processes). In our experience with such projects, we have found that there tends to be a strong focus on hard infrastructure, while soft infrastructure is often neglected.

Middle Eastern ports have built world-class facilities and earned the respect of port and shipping industry participants globally. To solidify these achievements, they must focus on making the right moves going forward. In an environment of declining utilization, success requires capturing more business opportunities, not constructing more berths and terminals. Building hinterland connections, strengthening customer relationships, adopting digital solutions, and fostering a robust business environment are among the ways that port stakeholders can maintain momentum. Success will promote prosperity not only for the ports themselves, but for the entire region.