For many companies, data governance is the business equivalent of flossing. They know it’s good for them, but they’d rather be doing something—maybe anything—else. Most organizations look at data governance as a “compliance thing” and do just enough to check the boxes on data privacy and security. Others embark on multiyear projects but delegate the work to IT, often creating a disconnect between governance and business impact.

Either way, companies risk sidelining one of their most potent catalysts for generating value. Robust data governance helps ensure that your data is accurate, consistent, and available to those who need to use it. That means better data fuels your algorithms and decision making, so your insights and choices become better, too.

But once companies move beyond compliance and look to build capabilities in order to successfully—and sustainably—manage data quality, they’re largely on their own. With no regulations prescribing what to do, it’s easy to get bogged down. So what’s the answer? To borrow from that old writer’s maxim: show, don’t tell.

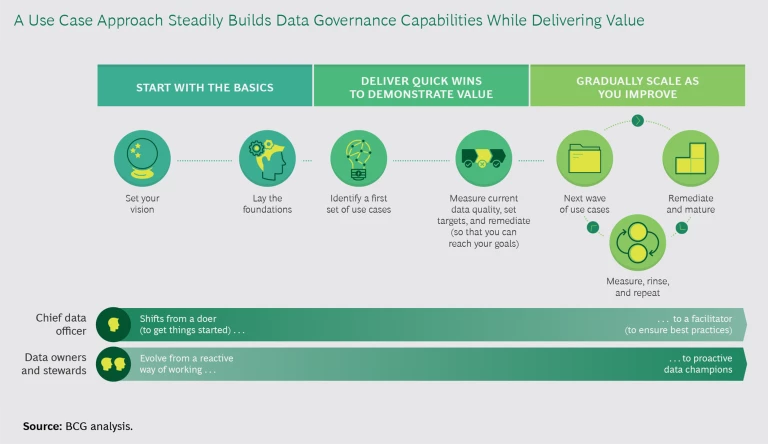

By delivering data quality for a few initial use cases, companies can achieve fast results while building the expertise, accountability, and foundations needed to scale.

The idea is to quickly demonstrate the value of data governance and build from there. By delivering the necessary data quality for a few initial use cases, companies can achieve results fast while building the expertise, accountability, and foundations (both technical and organizational) that help them scale.

This approach requires collaboration between the business side and IT. It also calls for new roles and even new mindsets. But the task isn’t Herculean. By following a clear process, companies can trim the fat—and the delay—out of data governance while maximizing the payback.

A Three-Point Plan

The nuts and bolts of data governance—the data structures, tools, roles, and policies—are not a secret. Yet in a recent BCG survey of some 600 companies, more than 60% of respondents rated their data governance capabilities at various levels of underdevelopment. What’s the holdup? Three common culprits are high expectations, limited resources, and a failure to recognize that data is a critical business asset, not something that’s “owned” by IT. But we’ve also seen some additional roadblocks:

- Governance focuses on data privacy and security, underemphasizing—or completely overlooking—the other dimensions of data quality, such as accuracy, completeness, consistency, clarity, and accessibility. As a result, companies hobble many value-generating uses of their data.

- Companies adopt a kitchen sink strategy, implementing practices and policies with no clear link to value creation. Biting off more than they can—or should—chew, businesses see frustrations, but not returns, mount.

A show-don’t-tell approach, driven by carefully selected use cases, creates a direct link between data governance and value. And it doesn’t do so quietly in the background. The key is to visibly remove a significant business pain point or enable a major business opportunity. And then, instead of basking in the success, you leverage the success, removing more pain points and enabling more opportunities. Steadily, you expand data governance—and its impact—across your data landscape.

So what does this approach actually look like? While the exact recipe varies from one company to another, a three-phase process can guide the way. (See the exhibit.)

Start with the Basics

The first step companies should take is to put overall leadership of their governance effort in the hands of a chief data officer, or CDO. Generally, this should be a senior business leader who can comfortably liaise with the business side, the analytics teams, and IT. The ability to straddle these worlds is crucial in linking governance to impact. Through their interactions, CDOs can understand—and communicate—business needs, technical capabilities and limitations, and what initial use cases make the most sense.

The best CDOs play a dual role at the beginning. They do a lot of the grunt work to get things started (such as joining forces with the business side to classify data into high-level domains). But at the same time, they build and educate the company’s nascent data governance organization. So as that organization matures, the CDO can hand over more responsibilities and accountability. Ideally, the CDO should become less of a doer and more of a facilitator, coordinating efforts, ensuring best practices, and sharing experiences and lessons learned across the company.

Companies should also establish a data council, typically composed of key data stakeholders (primarily data owners, but IT chiefs, data privacy officers, and analytics and security experts often round out the group). This committee sets the vision: a common view of what the company wants data governance to achieve and how it plans to get there. And it continues to shape the vision as capabilities and goals evolve. Crucially, the data council sets measurable—and reasonable—targets and identifies KPIs that allow it to monitor and steer the transformation.

Deliver Quick Wins to Demonstrate Value

The next step is to identify, and build data governance around, a few initial use cases. (Generally, two to five use cases make for a good start, but you should factor in the size of the company and data team as well as the scope and complexity of the use cases before settling on a number.) Essentially, you want to take a business problem or opportunity and show how better data quality (the fruit of good data governance) brings better results.

Since a key aim is to deliver rapid results, you don’t necessarily need to put in place world-class solutions and capabilities. Indeed, you should keep things simple in this early phase and avoid introducing complex processes and tools. As you gain experience, you can turn up the dial.

When well executed, this approach brings multiple benefits. For starters, it delivers value. It also sparks business buy-in for data governance because seeing is believing. And it lets you build data governance capabilities in a gradual, prioritized way since you’re building only the capabilities your use cases require. That way, you don’t boil the ocean and, as often happens with that approach, burn your bridges.

Of course, some use cases are better suited than others for your first wave. While there is no fixed blueprint for identifying the best candidates, you should look for certain things in an initial use case:

- It is visible to senior management (leaders are aware that data is hindering a business opportunity or creating a significant pain point or risk).

- It will have a high impact for the business once data quality is improved.

- It doesn’t require overly complex remediation—so the payoff from ensuring high-quality data will come quickly.

- It involves a few data domains within the company (to make sure that the effort isn’t limited to a specific business area or function) and will introduce a few data governance capabilities (so as not to be too simple).

One example might be a targeted email-marketing campaign that, owing to deficiencies in the way contact and demographic information is captured, fails to reach many relevant customers. By implementing the right data governance capabilities, the company can sustainably ensure data quality, improving the campaign’s performance and delivering a business impact—more sales—that gets noticed.

This example highlights an important point: selecting the right use case really just gets the ball rolling. You also need to determine what data the use case requires, define what “good” data looks like (and see how your current data compares), and implement the appropriate governance to fill in the gaps.

Here’s where the organization you created in the “basics” stage—the CDO office, the data stewards, the data owners, and so on—plays a key, but not solo, role. In defining data quality targets, homing in on the root cause of any gap, and identifying appropriate remediation, the data governance organization needs to work closely with the business.

Consider how the process might play out for our email-marketing campaign. Looking to understand why its campaign isn’t reaching customers as expected, the marketing team suspects that many email addresses may be fake or otherwise invalid. The team raises this possibility with the data steward for the “customer” domain as well as the CDO office, who then extract data from a prior campaign and discover that almost 50% of emails bounced back. The marketing team notes that for its campaigns to be effective, no more than 10% of the active customer base should be associated with invalid email addresses.

To meet that goal, the data steward and the CDO office need to look for the root causes of the problem and ways to address them. They discover that customers who don’t create an online account can essentially enter any email address they want: the company has no validation process. And, indeed, these customers account for 80% of the invalid addresses. So the data steward and CDO office implement new validation processes. (Typically, they work with the relevant data custodian to design the solution, and implement it after signoff by the data owner and business sponsor for the marketing campaigns.)

Often, the discussions among stakeholders reveal additional issues to tackle. For example, perhaps the organization has no set definition for an “active customer” throughout the business. So in parallel with deploying the new validation processes, the data governance organization needs to work with relevant data owners to harmonize on a definition. This ensures that everyone is using the term “active customer” consistently across the business.

Through this kind of collaborative process, companies develop and improve their data governance capabilities. While an email campaign is a relatively simple use case, the general approach—homing in on the data required, deciding what good data looks like, and designing governance to get that high-quality data—can be extended to more complex use cases, such as those involving artificial intelligence (say, a recommendation engine that suggests products according to a customer’s online behavior).

And this approach has another upside: you’re never doing too much. And conversely, you’re never doing too little—your governance activities are just right, tailored expressly for the use case at hand. Meanwhile, your data governance organization is gaining experience and maturing, your business side is seeing the value in this stuff, and you’re putting in place some initial data governance capabilities.

Gradually Scale As You Improve

Now it’s time to leverage the momentum from a successful first wave. This means identifying and prioritizing more use cases—and implementing more governance capabilities. It’s an ongoing, cyclical process, in which you’re steadily evolving and expanding data governance. And because your use cases are always linked to business needs and impact, you’re also delivering more and more value.

How do you find these new use cases? Some are likely to develop simply in the normal course of business: problems to solve, opportunities to seize—if only you had high-quality data. But others will stem from a heightened awareness of what data governance can bring, an awareness that will steadily grow, across the company, as more use cases come online and more people notice the results. The successes fuel ideation: everyone starts thinking about how better data can make a difference for them, too.

Use cases can spark business buy-in for data governance because seeing is believing.

As the backlog grows, it’s important to push the most promising use cases to the top. Here the data council comes into play, meeting regularly (every few months perhaps) to vet and prioritize ideas. With an ordered list in hand, you can take the top-ranked use cases and apply the same process as in the first wave: determine the data you need, define good quality, and develop just those governance capabilities that will help you reach your target. And when you’re done, you repeat the cycle.

With each iteration, the processes become more familiar and more streamlined. Data owners and stewards grow more experienced and work more autonomously in their roles. And steadily, your data governance capabilities—and the organization around them—mature.

As that maturity sets in, savvy companies often implement advanced data governance tools. These are third-party solutions that are generally complex to implement (which is why you want to avoid them in the early phase) but can really step up your game. Some tools help data stewards identify data quality issues, others automate some of the data cleaning, still others help manage business glossaries and data dictionaries. The list goes on.

Finally, you need to measure—relentlessly—data quality and the maturity of your data governance capabilities. Knowing where you stand is essential for knowing where you need to go (what sort of course corrections may be necessary as you pursue your targets). Tracking KPIs is also a good way to ensure accountability.

Measurements should be taken on a regular basis, whether at the end of each wave of use cases or on a set schedule. It’s also important to communicate the results. The data council is a great forum for sharing updates and aligning on where—and how—to improve, accelerate, or pivot.

The successes of early use cases fuel ideation: everyone starts thinking about how better data can make a difference for them, too.

Key Principles of Success

The three-phase approach isn’t theory; it’s been battle tested by different companies, under different circumstances. Their real-world experiences have also demonstrated how several core principles can ease the journey.

Make Sure the Business Side Drives the Transformation

Data governance is a business topic, and the use case approach really underlines this. What problems do you want to solve? What opportunities do you want to pursue? How do these translate into specific data needs and what does good-quality data look like? These are hard questions to answer when data governance is led by IT or by someone coming at it from a regulatory perspective. The business side is closest to the data—and the ways in which it is created and is, or should be, used. Accordingly, the business should drive the data governance transformation (with strong support from IT), and data owners and stewards (who play an essential role in scaling data governance capabilities) should generally come from the business ranks.

It’s also a good practice to appoint a clear business sponsor for the transformation, ideally a senior executive whose mandate spans the company (eliminating any bias for a specific business area). Business sponsors can help the data council make certain decisions more quickly and efficiently. They also can promote and advocate for the data governance program with other senior leaders.

It would be great to simply plug in the roles, processes, and culture that data governance requires—but that’s not how it works.

Focus on—and Facilitate—Change Management

It would be great to simply plug in the roles, processes, and culture that data governance requires. But it’s not very likely. So change management is essential. In the beginning, this is a fairly localized effort, with the CDO team onboarding and training the initial members of the data governance organization (culled from the existing workforce).

After the company tackles its initial use cases and builds some early capabilities, it should then widen the focus—and the reach—of change management. This means developing communications plans and training initiatives to raise awareness and adoption of data governance across the organization. Some companies have introduced what they call “Data Days” to showcase initiatives, share their roadmap, and spark excitement about a data-driven business—and ideas for succeeding as one.

Define Clear Accountabilities

Over time, the data governance organization will grow and mature. As it does, roles and responsibilities are likely to shift. In the beginning, the CDO should assume much of the ownership of, and accountability for, the transformation (as such, the CDO needs to ensure that sufficient staffing is in place to get the engine going). But as use cases come online, and the organization and capabilities evolve, data owners and stewards will take on more responsibilities. It’s crucial to be clear, throughout this evolution, about objectives and accountabilities because they will shift.

Aligning the right metrics with the right stakeholders is a great way to create accountabilities while steering the transformation in a data-driven way. The breakdown should generally look like this:

- The CDO is accountable for KPIs associated with the maturity of capabilities.

- Data owners and stewards are accountable for key quality indicators for their respective data domains.

Some companies now incorporate these KPIs, along with data quality targets, into annual objective setting and performance reviews.

Create Communities

Bringing together data stewards, owners, and other members of your governance organization helps spread the word about best practices and pain points (and fosters collaboration and solutions). Communities are knowledge bases, sounding boards, and motivators. And it’s important that everyone involved in the data governance effort feels that they are part of a community. Organize opportunities to meet, share reports from the data council—and share achievements, too.

Companies often view data governance as a chore. They should see it, instead, as part of the fabric of running their business. By focusing efforts in the right places at the right times in the right ways, companies will find a very real—and very visible—link between data quality and value. They’ll take a pragmatic and effective approach to building the capabilities they need. And they’ll come to realize what some forward-thinking companies have already discovered: good data governance isn’t a burden or something just for the techies—it’s a competitive advantage.