An emerging form of blended financing and project structuring reaches out to private sector investors as partners in initiatives to benefit displaced communities.

Introduction

Even before COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, more than 500 million people globally were living in fragile settings, according to the World Bank. In fact, the number of forcibly displaced people worldwide has more than doubled since 2012. Contributing to this unprecedented increase are the 12.2 million Ukrainians who, according to the UN, have sought refuge in neighboring countries or are thought to be displaced inside the war-torn country. With existing relief resources stretched beyond capacity, the humanitarian ecosystem is intensifying its efforts to develop new financing models and new types of partnerships with business. Among the most promising options that these endeavors have identified is a form of blended financing and project structuring now known as humanitarian and resilience investing (HRI), which leverages private sector capital to deliver initiatives benefiting humanitarian and fragile contexts.

Humanitarian and Resilience Investing (HRI)

For years, BCG has worked with various organizations in the humanitarian ecosystem, from UN entities such as the World Food Programme (WFP) to development finance institutions (DFIs) aiming to increase the amount of private sector capital in their transactions. In 2019, the World Economic Forum (WEF) launched an HRI initiative to bring the humanitarian ecosystem, development partners, entrepreneurs, and investors together, uniting public organizations such as the World Bank and the European Commission, humanitarian organizations such as the International Committee of the Red Cross and the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, and private sector investors such as Credit Suisse and Lombard Odier in a sustained effort to accelerate progress on humanitarian investment opportunities. Since then, BCG has continued to support this effort. In 2019, we published Humanitarian Investing: Mobilizing Capital to Overcome Fragility in partnership with WEF, and highlighted five key challenges that were hampering HRI market expansion:

- Lack of organizational readiness

- Limited awareness of new financing instruments and approaches

- Insufficient application of de-risking capital

- Lack of collaboration among main stakeholders

- Insufficient number of humanitarian and resilience programs structured for investment

Since 2019, stakeholders have increasingly recognized the potential of HRI, and some progress has been made toward creating a large-scale HRI ecosystem. However, blended finance, whose lens extends slightly beyond HRI, has not advanced over the last decade, and data from 2020 indicates that blended finance capital flows fell by 50% from 2019 numbers, according to research by Convergence, a global network for blended finance.

Why is this the case?

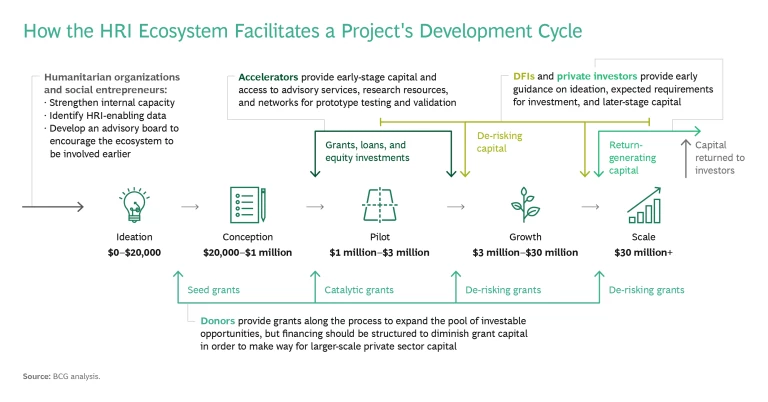

The development cycle of an individual HRI opportunity is more complex than that of a typical private sector investment opportunity, because the focus on fragile settings requires the involvement of more organizations, earlier support from critical stakeholders, and additional resources to address the challenges of operating in fragile markets. This complexity arises organically from the fact that HRI targets investments that address needs emerging from the prospect of natural disasters, instability, and conflict. (See the exhibit.)

The question, then, is this: what needs to be done to overcome these challenges?

Progress Against Key Challenges and What Remains to Be Done

Revisiting the five key challenges that we identified in Humanitarian Investing, we see areas of progress and areas where additional effort is urgently needed.

Organizational Readiness: Creating Capabilities but Needing Change Management

Leaders of humanitarian organizations are moving beyond their traditional focus on acute crisis response to focus on crisis prevention and on the long-term resilience of displaced populations. In doing so, they are recognizing the benefits of market-driven, sustainable solutions and have started to build teams, often called sustainable finance teams, that have a mandate to glean practical insights from market economies and to engage with the private sector.

Often, other parts of the organization—most notably the project teams that develop projects in response to humanitarian needs—have a poor understanding of sustainable finance teams’ work. Moreover, because making private sector involvement an organizational focus means departing from traditional ways of working, sustainable finance teams often encounter internal resistance to adopting models that can generate a return for investors. As a result, some organizations seeking financial sustainability and funding for their projects may try to retrofit old models that were never intended to involve the private sector, rather than develop business models designed from the outset to attract commercial investment.

It is critical for leaders of humanitarian organizations to communicate to all levels of the organization—not just to sustainable finance teams—the benefits of leveraging private sector capital. One key argument to share is that bringing in the private sector reduces demand for humanitarian financing, meaning that the organization can use valuable donor funds differently in crisis prevention (for example, to de-risk a project at a later stage) and can redeploy them to projects that address acute crises in the most difficult contexts. Moreover, increasing the resilience and self-reliance of vulnerable communities reduces the overall need for humanitarian financing. With these benefits in mind, leaders should secure buy-in for HRI opportunities within humanitarian organizations as soon as possible, as doing so facilitates innovation and provides support for each stage in the development process.

DFIs, on the other hand, have aligned on the value of helping to secure private capital alongside their investments, and many have adjusted their strategies accordingly. Nevertheless, DFIs need to treat securing private capital as a KPI to be monitored. Additionally, DFI’s need to devote more of their expertise to supporting humanitarian organizations in structuring programs and projects for investment against various return expectations.

Financing Instruments: Moving from Awareness to Understanding

Organizations have made progress in raising awareness of new financing instruments. In addition to convenings of WEF and publications from organizations such as Convergence, other groups have taken action. The Toilet Board Coalition, for example, assembles roundtables to drive private sector engagement in guiding sanitation projects through their development cycle and corresponding financing cycle.

Although more remains to be done within humanitarian organizations to increase awareness of new financing instruments in the context of investing in fragile settings, the greater challenge is to deepen the understanding of how those financing instruments actually work. Most critically, project ideation should always start with addressing the humanitarian need and then shift to determining which financing instrument can best support it, rather than the other way around. A humanitarian organization can ensure correct understanding and operationalizing of financing instruments by involving the private sector in this early stage of project development and invite in their expertise to adjust the design of the project toward increasing its potential for investment.

Accelerators

De-risking Capital and Insurance: Overcoming the Uncertainty

Donor money in the form of seed and catalytic financing remains an essential component of support for early-stage progress for opportunities led by humanitarian organizations. In addition, owing to the higher-risk profile of investments in fragile contexts, later-stage de-risking capital from third-party donors, including foundations, is necessary to offset the risks that discourage private sector investors from participating in fragile context investments. Traditionally, donors want their money to have an immediate, direct impact and are comfortable giving funds as direct support. However, donor money would go farther if organizations were willing to de-risk through blended financing. Unfortunately, many donors are uncomfortable backstopping returns or protecting private investors against loss, even when doing so yields greater impact. Foundations and their endowments have an increasingly important and special role to play here. They can "give" (use their direct philanthropy in catalytic and de-risking grants), and they can "invest" (use their endowment dollars in the blended stack, which, at a minimum, preserves principal and immediately generates positive impact). The foundation can therefore multiply its annual impact through being both a grant-maker and investor.

De-risking requires donor money, but it also requires investment from DFIs willing to hold a mezzanine-level note to protect private investors from catastrophic loss. For example, Finance in Motion, an impact asset management company, developed and operationalized various public-private funds with layered shareholdings. In one structure, for example, the German government and the European Commission provide public capital as a junior-share loss-absorption layer; DFIs including the Dutch Entrepreneurial Development Bank (FMO), the Development Bank of Austria, and Germany’s KfW Development Bank hold mezzanine shares to protect private investors; and banks, family offices, and high-net-worth individuals hold more secure senior shares or notes.

DFIs must also begin expanding into new regions before opportunities are ready for investment, in order to help de-risk the market environment for private investors. By entering the market before viable investments are available, DFIs can contribute to building ecosystem infrastructure that will give investors the confidence to engage.

For example, in 2020, to accelerate Nepal’s growth, FMO began exploring ways to attract more investments to support the development of the country’s private sector. Following a fact-finding mission and a market assessment, the bank realized the need to do more work to prepare the private sector for increased investment from DFIs and private sector players. Accordingly, FMO joined hands with British International Investment (BII) and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) to identify local partners, generate opportunity leads, and build capacity in the country. Following the initial evaluation phase, FMO, BII, and SDC now aim to engage in a longer-term market-building program to unlock patient and flexible capital to support private sector growth and innovation.

Stakeholder Collaboration: Starting Earlier in the Development Cycle

Although we have started to see better collaboration within the HRI ecosystem, some individual HRI opportunities advance too far in the development cycle before the collaboration begins, rendering them nonviable for leveraging private sector capital. The solution is to initiate the collaboration at the beginning of co-creation of a project—even before formally involving private organizations. Early collaboration also promotes the use of common terminology, transparency with regard to market size and growth potential, and the development of robust data and analytic frameworks that permit systems-level measurement of impact.

In addition, early partnership increases trust between organizations. Once humanitarian organizations see the private sector not merely as philanthropic donors, but also as implementation partners with relevant experience and innovative capabilities, it becomes easier to develop investment opportunities that achieve both impact and financial returns.

Moreover, earlier involvement helps private sector organizations improve their understanding of fragile market dynamics. Armed with this knowledge, they can more effectively tackle barriers, such as outmoded notions of the investment market and regulatory hurdles, and develop project roadmaps that address misconceptions about and plan responses to anticipated challenges within the operating environment.

Finally, earlier involvement brings expertise to enhancing project design in ways that make projects more attractive for investment. For example, connecting a project to other infrastructure investments or expanding the portfolio of projects within the investment offering can improve risk-adjusted returns.

Investable Opportunities: Expanding and Positioning the Spectrum of Options

Humanitarian organizations and social entrepreneurs have yet to develop a robust and continuous supply of programs and project opportunities structured for investment in a way that meets investor standards. That shortcoming is due in part to issues noted throughout this perspective. Should the challenges mentioned earlier be overcome, the pipeline of investable opportunities will certainly increase.

That said, opportunities for investment are already available. But even when HRI opportunities achieve a level of sustained growth and are ready to attract commercial sources of capital, their investment size may be too small for many commercial investors to consider. Such investors need to deploy funds at scale and are guided by incentive structures that are inappropriate for smaller investments. Further, a lack of data, significant legal barriers, high market-entry costs, poorly functioning markets, and outsize political and counterparty risk may combine to render these opportunities too risky for many capital providers, given the expected returns.

On the other hand, when organizations develop impact-first concessionary-return funds that might be attractive to impact-focused asset owners (such as high-net-worth individuals who want to create impact as well as earn a return), intermediary asset managers often face barriers to sharing the opportunity. Specifically, the funds produce below-market returns, and the investable opportunity requires too large a minimum for high-net-worth individuals to consider investing in them.

Although an asset owner with fiduciary duties, such as a pension fund, faces unavoidable difficulties when reviewing a concessionary product, an ultimate asset owner should be able to invest in an impact-first concessionary-return fund. To reach this audience, intermediary asset managers must understand, package, and position opportunities for end investors to consider as part of their portfolio. This can be structurally challenging.

For example, one private bank found concessionary return-generating blended finance opportunities in fragile markets interesting, but the bank was organized in a way that precluded it from offering submarket-return investment options to its clients. Asset managers must present these opportunities to asset owners in ways that make sense for them, generally as return-generating substitutes for pure philanthropy that provide substantial impact multiples on capital invested. Framing the opportunities in this way would help asset owners move beyond current thinking—which assumes a dichotomy of market returns on the one hand and pure philanthropy on the other—and push their asset managers to revise their constellation of investable categories to include risk-tolerant, concessionary investments and funds that expand their role in humanitarian contexts.

Asset managers—and corporates more broadly—can also invest in opportunities that adjust existing financing mechanisms in support of fragile communities. For example, leading players in the private sector have shown a clear willingness to pay a premium for refugee-generated carbon credits, and the barriers to supporting this opportunity seem minimal, given existing familiarity with the purchase of carbon credits.

Conclusion

Without innovation in funding models, the gap between available funding and the money needed to provide humanitarian and resilience assistance and resources to a rapidly expanding global population facing fragility and displacement will continue to grow, leaving millions increasingly vulnerable. Progress in efforts to address this gap has been slow. Although there is a greater understanding today of the need and potential for humanitarian and resilience investing, such investing requires collaboration and innovation to pioneer projects and investments at a scale that will enable them to make a real impact. It is time for each organization, particularly the DFIs as catalytic actors, to recognize its role within the ecosystem and commit to scaling HRI funding and impact to crises and fragility—a process that entails reviewing internal strategy, revising KPIs and incentives, and establishing and scaling new types of partnerships.