Companies take three key actions to find talent in new and hidden places.

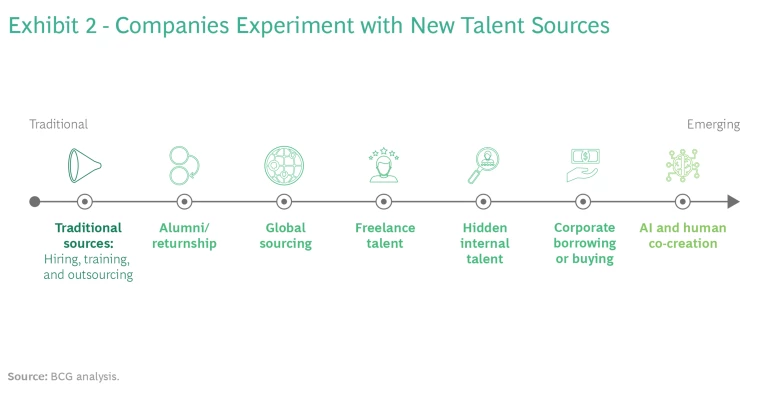

Rapidly changing workplace dynamics over the past decade and especially during the Great Resignation are forcing company leaders to tap into what we call “fluid talent.” Rather than just drawing from traditional sources, they should look to former employees and freelancers as well as talent that is hidden elsewhere in the company, borrowed from other companies, or working in other geographic markets.

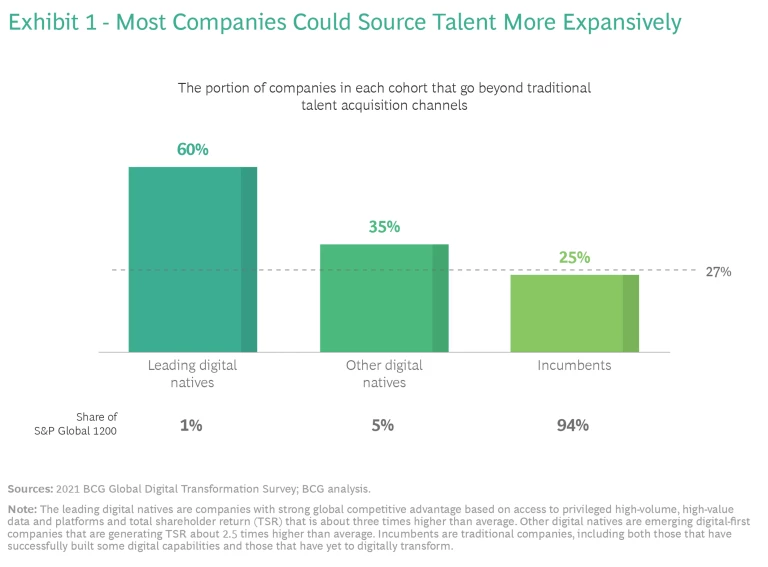

While nearly all companies understand the urgency to find new sources of talent, few are going about it systematically. According to a BCG survey of more than 700 executives responsible for digital transformation, fewer than one-third of companies today go beyond traditional talent acquisition channels. (See Exhibit 1.)

Companies struggle to identify where to look within and beyond their organizations to find fluid talent. They are overwhelmed by the exploding number of digital talent platforms—such as Fiverr, Toptal, and Upwork—and the complexity of managing so many talent sources and solutions. Even companies that embrace fluid talent may not fully adapt their operating models to get the most from new sources of talent.

A fluid talent approach requires a fundamental shift in people management. It blurs the lines between external and internal talent sources, asks HR to play new roles and engage differently with technology, and subtly shifts the dynamics between companies and their workers. It also asks managers to shift their thinking about their teams and ways of working, moving from “owning” to “accessing” talent. How can companies take fluid talent from a nice concept to a concrete set of actions that create business value?

On the basis of dozens of interviews with Fortune 500 leaders, a detailed survey of more than 100 HR and business leaders, analysis of the HR technology landscape, and our work with clients, we find that companies aiming to make this transition should take three actions:

- Identify where a fluid talent model will deliver the most value for the organization.

- Create an ecosystem of partners, including talent matching platforms and solutions for upskilling and reskilling employees.

- Develop a fluid talent operating model that reengineers how work is done and careers are built.

Companies do not need all the answers to begin their journey. Their early steps can generate wins on which to build a full talent transformation.

The Promise of Fluid Talent

Finding and retaining the right talent is growing more challenging. The skills gap is widening, while the half-life of skills shrinks and the need for expertise in areas like digital expands. At the same time, workers’ expectations have changed. People put a greater premium on workplace flexibility, autonomy, and purpose, a shift that is contributing to high levels of attrition. These dynamics are encouraging companies to experiment with a range of fluid talent initiatives. (See Exhibit 2.)

Alumni and Workforce Returnee Programs. Companies such as Amazon and Goldman Sachs are increasingly offering return-to-work, or returnship, programs that ease the path back into the workforce for alumni and other experienced workers. The programs offer combinations of pay, training, and mentorship. Unilever’s U-Work program, for example, aims to break the compromise between gig and traditional work models, enabling alumni and even current employees to work on specific assignments like a contractor or freelancer but have guaranteed pay and benefits. Parents who took time off to care for children are one of many target populations of these programs. Both alumni and returnees are attractive to employers: Alumni already know the organizations, and returnee populations include individuals with strong prior work experience.

Global Talent Sourcing. Organizations, including the customer service division of one of the world’s largest tech companies, are removing location constraints for job openings and opening hubs near attractive talent pools. Automattic, the creator of Wordpress.com, has more than 1,980 employees in 96 countries and has had a fully remote work model for more than 15 years. Once a rarity, models like this are becoming more common as companies rethink work models amid COVID-19. The list of companies that have announced plans to allow employees to work from anywhere indefinitely continues to grow. Salesforce, for example, has shifted to posting jobs by time zone, rather than by city.

Hidden Internal Talent. Companies like Seagate Technologies are creating internal talent mobility programs to better match existing employees with internal project needs and job opportunities, unlocking hidden capacity, helping their organizations respond more quickly to market opportunities, and enhancing career development for their teams. Nearly 90% of all eligible employees registered for Seagate’s Career Discovery platform within 45 days of its launch, and the company estimates that it unlocked 35,000 hours and saved over $1.4 million in external contractor costs in the first four months of the program. Unilever used its internal talent mobility platform to move more than 9,000 employees from one job to another in the early days of the pandemic and estimates that it unlocked close to 1 million hours through the program.

Freelancers. In past work with Harvard Business School’s Managing the Future of Work program, we discovered that nearly two-thirds of companies report medium to extensive use of freelance platforms and that almost 90% of business leaders expect that digital talent platforms will be at least somewhat important to their organization’s competitive advantage.

Bridgestone, for example, worked with Toptal, a network of freelance software developers, designers, finance experts, and project managers, to streamline the process of retreading, or adding rubber, to tires to extend their life. The arrangement allowed Bridgestone to access skills that it did not require full-time.

Corporate Borrowing or Buying. During the early days of the COVID pandemic, Sysco, the world’s largest food distributor, and Kroger, the supermarket chain, entered a talent sharing agreement in which furloughed Sysco workers were offered temporary employment at Kroger distribution centers. And Royal Philips, a leading health technology company, and Walt Disney Company partnered to test the use of storytelling, animation, and cartoon characters during MRIs performed on children—softening the hard edge of a loud, often claustrophobic experience.

Human-AI Co-Creation. Airbus, an aerospace manufacturer, teamed up with Autodesk, the design and engineering software company, to create an airplane partition that is 45% lighter but just as strong as current models. The companies relied on “generative design,” an AI-enabled process in which humans give design parameters to the software, which in turn creates thousands of alternatives, learning from each iteration.

Fluid talent approaches can broaden opportunity and team diversity.

These initiatives suggest the potential of a fluid talent model to better meet talent needs today and adapt to changing skill requirements tomorrow. Managed carefully, fluid talent approaches may also create more equitable opportunity and diverse teams. Digital talent platforms, for example, can remove elements such as race and appearance from the hiring decision. And companies that make opportunities broadly visible often see greater applicant diversity. Since Schneider Electric implemented its Open Talent Market, for example, women have received 55% of the assignments.

Fluid Talent in Action

If the promise of fluid talent is clear, bringing it to life is not. Executives often talk about the need for fluid talent, but at most companies no one takes responsibility for it—or has clear ideas about developing it.

Some companies, however, have broken away from the pack. In particular, a handful of leading digital natives—including Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta, Microsoft, and Netflix in the US as well as Alibaba, Baidu, and Tencent in China—more commonly go beyond traditional talent acquisition channels. In BCG research, about 90% of survey respondents from these companies reported the ability to rapidly adjust to changing talent demands across teams.

How can more companies be like this group? We found that there are three keys for companies to unlock fluid talent advantage:

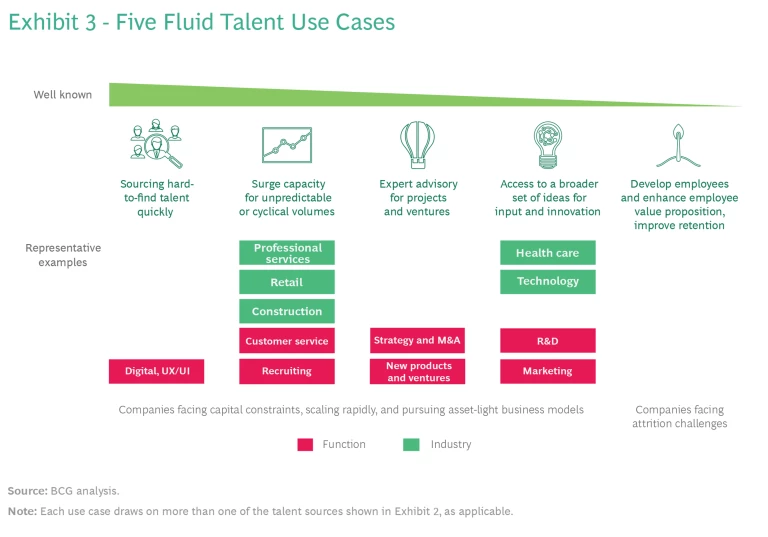

Identify the highest-value use cases. Five use cases represent high-value opportunities for many companies. The most well-known are quickly finding specialized talent and managing fluctuations in demand for talent. These are opportunities for many companies to experiment with new talent sources while maintaining a flexible cost base. For example, Microsoft partnered with Limitless Technology to help manage surges in customer service queries. Limitless developed a network of Microsoft brand advocates to respond to customer queries. Given the experts’ existing product knowledge, they quickly became effective in their roles. Microsoft observed faster response times, lower cost, and similar customer satisfaction with the Limitless workers.

Companies are also using fluid talent in other, less well-known ways. Some companies are relying on fluid talent to provide expert advisory on projects and new ventures, innovation, and skill development and career advancement. Strategy and corporate finance functions, for example, often use the expert advisory model for special projects. In another approach, the Italian energy company Enel partnered with crowdsourcing platform InnoCentive to enlist the help of hundreds of thousands of potential problem solvers to identify more than 5,000 new ideas.

Many of these use cases are applicable within specific industries or corporate functions. Exhibit 3 provides a broad overview of where use cases may find a home and the sources of talent within which companies can search.

Depending on their maturity, market position, and location, companies will have different needs. Companies should pursue the use cases that meet their specific needs, rather than those that are popular or those that have been adopted by competitors. Allianz, for example, launched its internal talent mobility platform after surveys showed that workers believed career opportunities were not transparent. The platform helped increase retention and employee development. Meanwhile, Seagate Technology launched an internal talent marketplace when it shifted its business model and needed to redeploy talent to new areas of the business.

Curate a partner ecosystem. The landscape for fluid talent has changed enormously over the past two years. Venture investors poured more than $12 billion into HR tech companies in 2021, more than three times the amount invested in 2020. Companies are offering more-sophisticated AI-powered tools for anticipating talent needs, skills assessment and inferencing, talent matching, and talent sourcing.

Even as they expand their offerings, none of these HR tech companies offers an integrated, end-to-end solution for fluid talent management. Consequently, companies need to work with several HR tech partners to meet their talent needs, coordinating with labor market data and assessment companies, recruiting partners, external and internal talent platforms, upskilling providers, and others.

In so doing, companies must consider the strength of tools from vendors, their product roadmaps and integrations with other offerings, and ease of use, especially when many enterprise users will be working with the solution. They also should evaluate how well vendors work with clients to enable employee onboarding and encourage adoption.

Support fluid talent with a new operating model. Companies that have experimented with fluid talent understand the need to adapt legal and procurement frameworks, rewire HR processes like performance management, build cross-functional project teams, and invest in change management. But to really unlock value from fluid talent, companies also need to rethink their ways of working and how they deploy and onboard talent.

BCG research has found that fewer than one-third of companies report that they can rapidly adjust to changing demands across teams. This is more than a sourcing challenge; it suggests that, beyond looking more broadly for talent, companies need to adjust their operating models to deploy talent more flexibly.

Beyond deployment, companies can help freelance, contract, and other fluid-talent workers learn the company culture and norms. They can develop a system of onboarding that spells out the unwritten rules—for example, by defining detailed norms at the start of a project—and ensure that managers model the desired behavior. They can also create programs to support new hires, such as assigning a peer to be a “culture buddy.” And they can use technology to make work processes more explicit. ByteDance’s Lark technology, for example, integrates software and collaboration tools so that work is visible to others in real time. Automattic uses its own collaboration space along with tools like Slack to improve transparency, broaden accessibility, and enable asynchronous and distributed work.

Of course, as companies revamp their operating models, they should build in controls to mitigate risks. This could mean more frequent reviews of the work conducted by freelancers and contractors or rerouting of the queries that gig workers cannot resolve to other teams.

Models for tapping into fluid talent continue to evolve as companies seek a broader range of talent sources and address the growing pains of a new working model. The matchmaking and enterprise contracting models for freelance talent, for example, are still a work in progress. Managers also need help redesigning workflows so that outsiders, whether they are alumni or freelancers, can pick up discrete assignments in a much longer stream of work. We expect to see more companies experimenting with their own novel programs, such as Unilever’s U-Work, that aim to capture the best of internal and external talent.

Whatever the mix of talent sources that they adopt, organizations that unlock fluid talent will be more competitive in a transforming market. They will create knowledge based on a richer and more diverse set of expertise, develop their people more effectively, and emerge ready to respond to market opportunities.

But before they can activate fluid talent, companies need a strategy for fluid talent. The leaders in the field have a clear understanding of how fluid talent will enable their strategy and purpose and a willingness to go beyond familiar partners and technologies to explore the art of the possible. They are also open to changing how they work, because it can unlock the value of fluid talent.

The authors thank colleagues Patrick Forth, Romain de Laubier, Saibal Chakraborty, Tauseef Charanya, and Matteo Magagnoli, whose work on digital transformation informs this article. Exhibit 1 relies on heretofore unpublished research conducted by that team.