Introduction

Cities have long been the cradles of innovation. For millennia, geographical proximity, population density, and skill diversity have been the ingredients that sparked waves of creativity. As they converge in cities, these factors intensify knowledge flows, triggering novel and disruptive ideas which explode economic growth.

Today, these dynamics that drive innovation and growth have only become more pressing as cities are racing against time to contend with the existential threat of climate change. The need for innovation is crucial to mitigate environmental risks and find long-term solutions for sustainable and resilient living.

In this context, the world is also undergoing its Fourth Industrial Revolution. Knowledge creation and transfer is supplanting traditional goods manufacturing as the core product of post-industrial cities. The composition of value chains is swiftly changing as well. Mental labor — intellectual property — is now the primary means of production; and the new physical economic hubs are universities, research institutes, and clusters of innovative companies. Those who do creative work for a living, like scientists, engineers, artists, musicians, and designers have become the ultimate economic resource — with cities now vying to attract them.

But creativity is a challenging resource to manage. First, global talent has become highly mobile. Remote working technologies adopted during the COVID-19 pandemic has uprooted people: The office — once the main determinant of where people lived — is now less important. Creativity is also not a conventional or tangible asset like mineral deposits or machinery. It cannot simply be hoarded, fought over, or bought; on the contrary, to attract and retain knowledge workers is a fragile and elusive process. And there’s no magical potion for creativity either. What works in one geographical context may not be equally effective in another.

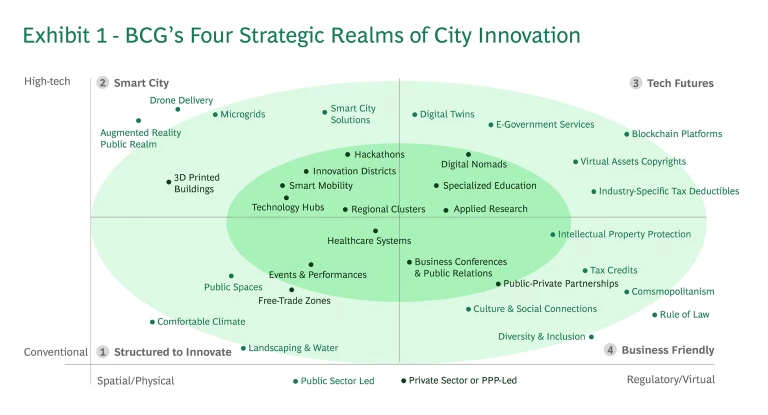

As we begin to understand how cities are succeeding at building and nurturing creative ecosystems, the below is BCG’s framework of common themes that urban centers around the world are pursuing to achieve this goal. Designed against a matrix of ‘High-Tech-Conventional’ and ‘Spatial-Regulatory’ criteria, the array of sought-after strategies reveals four distinct types of interventions: Good Urban design, Smart Cities, Tech Futures, and Business Friendly realms.

With varying degrees of leadership, partnership models, and stakeholder involvement, the private sector dominates the mundane (central zones of the framework), while it is incumbent on governments to expand the frontiers to support new innovative markets. This article presents how this is happening with exemplary cases from global cities leading the way.

BCG’s Four Realms of City Innovation Strategies

1. Structured to Innovate

To a highly mobile creative class, one of the most important determinants of where to live is psychological, says urban studies theorist Richard Florida. “Where we live is important not only because it provides access to jobs, but because it has a deep effect on our happiness and well-being.”

Cities of Choice, a recent report published by the BCG’s Global Center for Future of Cities and the Henderson Institute, references several soft dimensions to cities that make people happy: a comfortable climate, cosmopolitanism, culture and social connections, good education and healthcare systems, and quality of the built environment.

Urban design can play a critical role in fostering such a happy environment. By creating diverse, accessible, and welcoming public spaces, cities can encourage residents to come together and interact. Just as Ancient Greece weaved the Agora into the urban psyche and early industrializing cities invented café culture, today, parks, plazas, and simple outdoor seating areas can be designed to nurture an attractive environment where people congregate.

These spaces can be equipped with free Wi-Fi and host public performances, art installations, and food markets, turning them into adaptable hubs of social interaction. As public spaces are made more inclusive, diversity in turn flourishes, multiplying the creative potential of a city.

Aware of this, mayors are leading the charge to transform their cities into more livable and resilient places to attract creative talent.

Examples abound. From Mayor Sadiq Khan’s plan to transform London into a National Park City boasting 50% green spaces to Mayor Anne Hidalgo’s vision of a car-free central Paris, to celebrating Copenhagen as the world’s most bike-friendly city. Toronto went even further to experiment with the short-lived ‘Sidewalk Labs’, the most ambitious attempt to create a first-of-its-kind sustainable neighborhood that integrates aspects of a smart city with sustainable living.

More recently, several city leaders from around the world gathered at COP28 in Dubai to advocate for funding to help them transform urban areas into net-zero emission and climate-resilient places with the aim of sustaining long-term, high-quality life for their residents.

2. Smart City

Smart City planning is a 21st-century trend. Although elusive in definition, common Smart City threads focus on adopting digital technologies in communication and information systems to revolutionize city operations.

This is mainly sought by employing technology to modernize services, infrastructure, and facilities creating leaner, integrated, and cost and resource-efficient processes. Investment in soft and hard tech infrastructures supports the discovery and development of new technology sectors. Of these infrastructures, innovation districts are envisioned to be anchor institutions where companies physically cluster and connect with start-ups, business incubators, and venture capital to oil the wheels of collaboration necessary for inventiveness.

Digital technology can also positively influence the creation of comfortable, efficient, climate-responsive, and robust cities. Applications here are endless: Smart water metering systems, real-time traffic management, autonomous vehicles, energy performance systems for buildings, to name but a few.

To say that almost every major city or region in the world today is targeting smart city transformations is hardly an overstatement. The list of examples is long.

For instance, the formation of an integrated medical technology regional cluster in Denmark/Sweden’s Øresund promises to create net growth in high-value employment along with major downstream opportunities. ‘Station F’ in Paris, a converted freight depot housing over 1,000 startups, is one leading innovation district acting as a catalyst for the tech industry in France. Masdar City is Abu Dhabi’s flagship smart city hub that commercializes clean technologies, monitors eco-efficient building operations, and experiments in shared, electric, and autonomous vehicle systems. Finally, by investing heavily in its digital twin model, digital national identity, and smart urban mobility, the Smart Nation Initiative aims to brand Singapore as the ‘Smartest City in the World’.

3. Tech Futures

Although technology is not a magic elixir for economic growth, when paired with talent it becomes a powerful force for disruptive innovation. Advancements in technologies are transforming traditional processes into digital workflows. Digital is in turn unlocking new businesses models that better streamline operations, improve customer experiences, and accelerate production and customization.

This shift has disrupted traditional industries such as retail, logistics, and manufacturing. It has also created new sectors that make use of data analysis, digital platforms, and cloud computing to improve efficiencies, increase productivity, enhance decision making, and personalize products.

City after city is joining the race to build up tech infrastructure and talent to reap the net benefits that such solutions and services can deliver. The objective is always to unlock new markets and growth trajectories.

The target is to nurture high-value technology-related sectors such as fintech, green technologies, artificial intelligence, robotics, software, and telecommunications and to attract the greatest number of talents by the lure of high-paying jobs and upward mobility. And not only are cities deploying every trick in the book to burnish a reputation as tech-friendly, but they are also taking one step further to surface new ideas or commercialize new tech-driven products.

Once more Dubai is a case in point as it is cementing its reputation as a digital forerunner. The organization of hackathons – such as the UAE Centennial 2071 – is one sponsored initiative that explores tech-driven solutions for mass rollout. The Dubai Blockchain Strategy plans to convert governmental processes onto blockchain platforms thereby increasing transactional efficiencies and creating thousands of new jobs.

And, in addition to hosting numerous global events on artificial intelligence and construction technologies, Dubai city government consistently spearheads its own digital transformation by initiatives such as the groundbreaking ‘Digital Assets Law’ that aims to ensure legal rights and boost tech investor confidence.

4. Business Friendly

Innovation necessitates supportive governance. That’s because, due to its inherent riskiness, multinational corporations, investors, and startups will all avoid deploying in markets without guarantees of political transparency, enforceable contracts, or ownership protection.

Fiscal support can cast a wide net to incentivize these stakeholders to do business in a certain jurisdiction. Incentives can take the form of R&D-related investment tax deductibles or tax credits and holidays. Legal support can help streamline patent applications and Intellectual Property or copyright protection. Finally, direct spending on specialized education, applied research, or free-trade and innovation zones can trigger a positive and attractive business environment conducive to creative talents and venture capital.

But supportive governance can also be more subtle. Fostering a culture of collaboration can go a long way in nurturing creative exchanges. Promoting partnerships between the public and private sectors, academic institutions, and community organizations establishes an environment in which cross-pollination of ideas can happen almost organically. They also ensure the best initiatives are capitalized and activated. Networking events, workshops, and conferences on cutting-edge themes bring together entrepreneurs, researchers, and business leaders to meet and establish long-term and mutually reinforcing business relationships.

Normally fiscal and legal regimes are the purview of national governments. Prominent examples are the UK government’s funding of 1,000 PhDs in artificial intelligence and its incentivizing partnerships through the Digital Skills Council. Still examples are plentiful of cities surmounting political challenges and leveraging national support for innovation. For instance, Saudi Arabia’s recent foray into the biotechnology sector is one direct public investment propelling Riyadh onto the front rows of a fast-growing commercial field.

In the UAE, Dubai is setting up a digital investors platform that supports streamlining new business permits, licenses, and fees processing. And the Abu Dhabi Investment Office Innovation Programme by the Abu Dhabi government is aiming to attract agri-tech, fintech, and ICT innovation investments by providing grants, equity, and other partnerships.

Conclusion

Humanity owes its prosperity to cities. And since cities are the center-stage of disruptive innovation, fostering growth can only succeed by supporting their capacity to attract talent and capital investments to innovate products that regenerate ever more productive and efficient value chains.

Although building innovative ecosystems has become an institutional priority, the task is anything but simple. Seeding and growing innovation requires employing the right mix of environmental, technological, and fiscal incentives, and so BCG’s Four Realm framework can serve as a tool for public stakeholders such as mayors and city departments and private actors as CEO’s and urban citizens to:

- Understand their positions across the matrix and assess their cities’ unique selling points.

- Benchmark what competitors are doing to achieve innovative strides and how their cities fare in comparison.

- Make informed decisions on potential relocation of business operations or place of living based on systematic criteria.

- Identify major as well as new potential opportunities across each of the four realms.

- Devise specific strategies to achieve short- and long-term goals of expanding outreach across and beyond the matrix frontier.

- Build strong implementation roadmaps for each strategy and engage stakeholders to execute with solid footing.

Almost three millennia ago, the poet Alcaeus presciently wrote that a city’s wealth lies “not in houses finely roofed, stone walls well built, nor canals or dockyards, but in the [people] able to use their faculties.” This remains very true and relevant today.