Manufacturing executives are having many sleepless nights lately—and for good reason. In just the last five years, they’ve weathered supply chain disruptions from a global pandemic, climate change, and military conflicts. In 2025, tariff volatility has added another layer of complexity.

And manufacturers now face an entirely new cost calculus—one that must balance traditional considerations with qualitative factors such as geopolitical risk, economic stability, and labor availability. To explore how companies are navigating these dynamics, the BCG Henderson Institute conducted a global survey of 1,000 manufacturing executives. (See “About the Survey.”)

About the Survey

We selected survey participants at random from 1,000 global companies that had at least 250 employees and $50 million in annual revenue. The companies represent a broad array of sectors: automotive, capital goods, consumer goods, energy, health care, information technology, process industries, and transportation and logistics. Survey participants were based in 19 countries with industrialized or emerging economies that include a substantial industrial sector: Brazil, Canada, China, France, Germany, Hungary, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Morocco, Poland, South Korea, Spain, Türkiye, United Arab Emirates, the UK, and the US.

We’ve identified five key insights from the survey which—taken together—reveal a sector learning how to operate in a changed context.

Cost Is Still King, but It’s Complicated

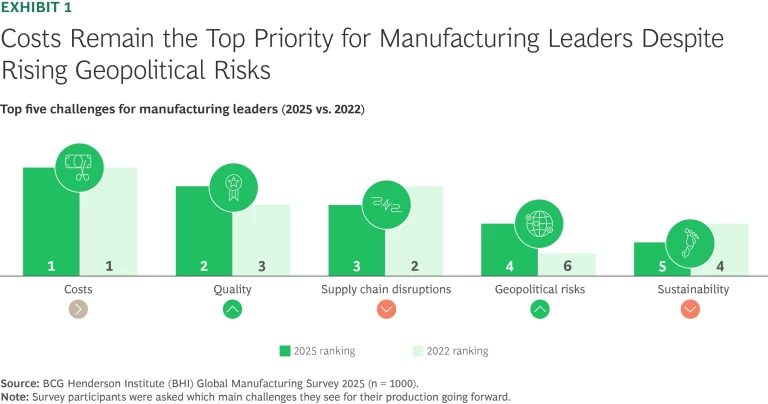

In the past, manufacturers in most industries followed a simple principle: go where production costs are lowest. Today, that decision isn’t as straightforward. In our survey data, manufacturing leaders continue to rank cost as their top challenge, consistent with our results from a similar survey conducted in 2022. (See Exhibit 1.) But the underlying reasons are more complex. Because of geopolitical risk and other factors, manufacturers have to optimize operations to offset the impact of tariffs or to compensate for the increased production costs from localizing their factories (in areas like labor and energy).

Elsewhere in the top five, manufacturing executives’ priorities have fluctuated. Geopolitical risks now rank fourth, just after supply chain disruptions. The latter dropped one spot from 2022, which is somewhat surprising given the events of recent years, including the pandemic, climate-related issues, trade tensions, and wars. One possible explanation is that those disruptions pushed manufacturers to make their supply chains more resilient through dual-sourcing, near-shoring, and other measures.

Tariffs Won’t Always Trigger Localization

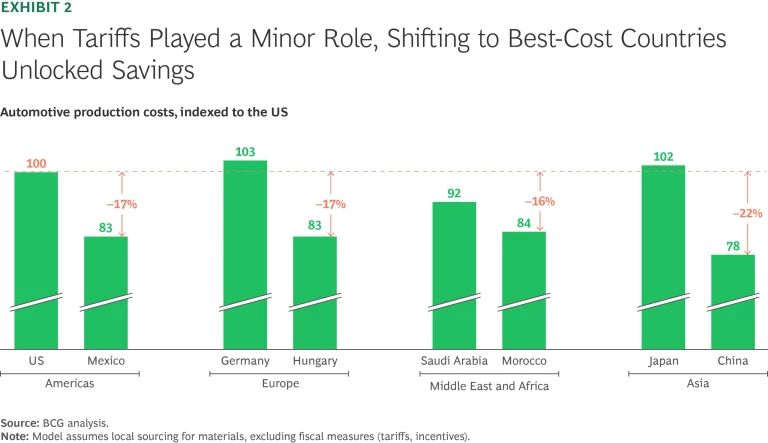

The cost calculus becomes tougher given that various tariffs under consideration can wipe out the advantage that low-cost countries previously offered, particularly in labor-intensive industries. Consider car manufacturing, where production in countries like China, Mexico, or Hungary can reduce landed costs to serve higher-cost markets like Germany or the US by 15% to 20% compared with domestic production. (See Exhibit 2.)

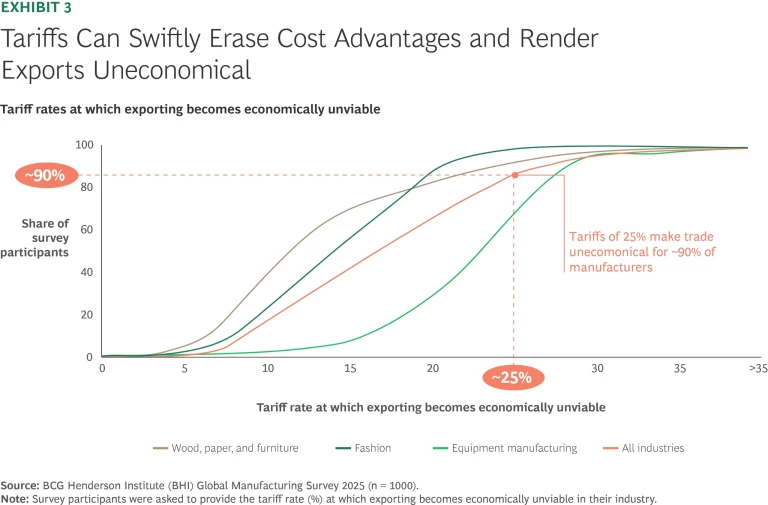

In today’s fractured trade environment, tariffs of 10% to 25%—realistic scenarios during trade wars—can quickly erase those cost advantages. Among respondents overall, 90% say that tariffs above 25% would make exports uneconomical. However, the threshold varies by industry—fashion firms feel the pressure with tariffs below 20%, while equipment manufacturers can absorb tariffs closer to 30%. (See Exhibit 3.)

Even when tariffs exceed the threshold where exporting becomes uneconomical, they do not automatically trigger localization. Production typically shifts first to other low-cost countries with more favorable trade terms that can still offer cost advantages over local manufacturing.

For example, if apparel exports from China to the US become unviable due to tariffs, production is more likely to move to Vietnam, Bangladesh, or India—not to the US, where labor costs would still be too high for a company to be competitive. Only if tariffs were broadly applied across all import sources would local manufacturing in the US become attractive—and even then, likely at tariff levels well above 20%. However, such localization would likely lead to significantly higher prices for consumers.

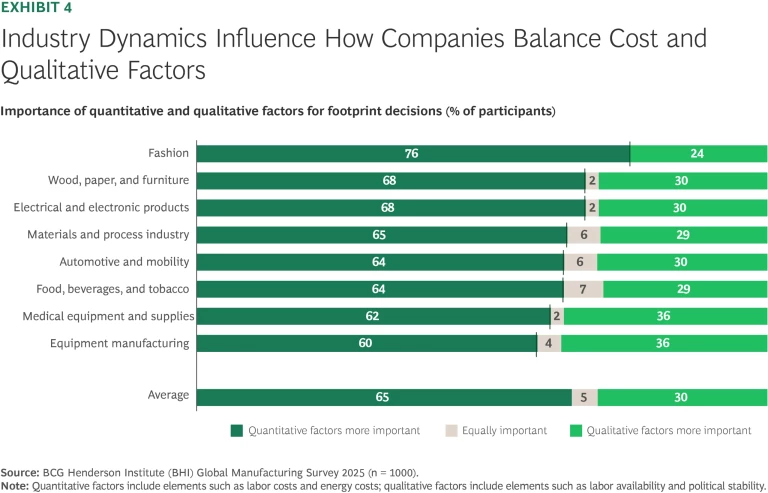

Qualitative Factors Can Tip the Scale in Some Industries

A striking 30% of our survey respondents report that qualitative factors—like labor quality and political stability—are more important than cost for footprint decisions. (See Exhibit 4.) The weighting depends heavily on the sector. Among executives in fashion, a cost-driven sector with high competition, 76% of manufacturing executives still prioritize low costs over other considerations. In contrast, in sectors where product reliability is crucial for customers who are less price-sensitive—such as equipment manufacturing or medical equipment and supplies—executives are more likely to cite qualitative factors as more important (36% for both sectors).

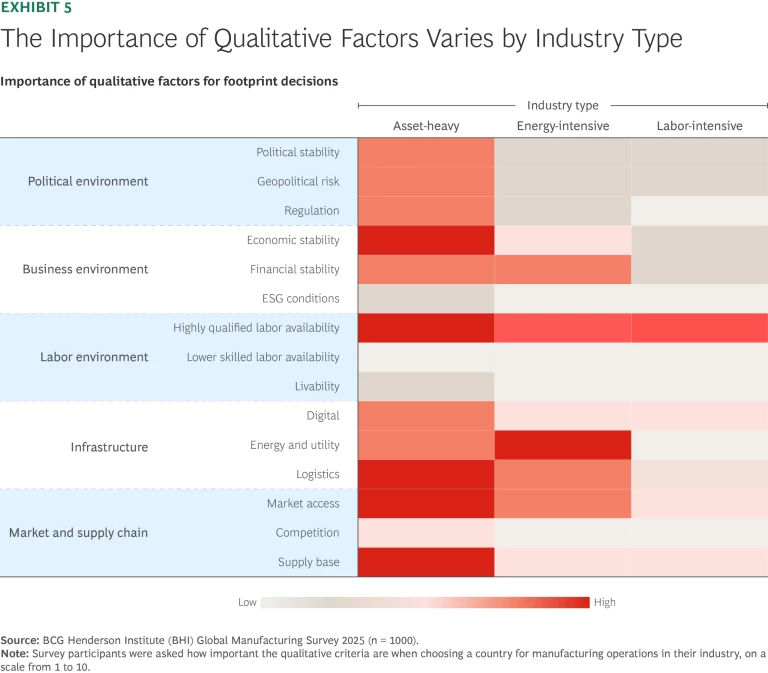

Drilling down one level, we considered five sets of qualitative clusters that can tip the scales in site selection for manufacturers, including the political and business environment, labor environment, infrastructure, and market and supply chain access. Across all companies, the availability of highly qualified labor is the most important dimension. But as Exhibit 5 shows, the relative importance of these clusters varies by industry.

Asset-heavy industries require stable markets for their production facilities (such as a semiconductor plant or a battery cell factory). These plants are expensive to build and need to run for many years. As a result, companies in these industries are more likely to say that all five clusters are important. Conversely, production facilities in labor-intensive industries (such as a wiring harness plant or an apparel factory) are easier to relocate to gain a cost advantage. For that reason, companies in these industries rely less on qualitative factors like political or economic stability.

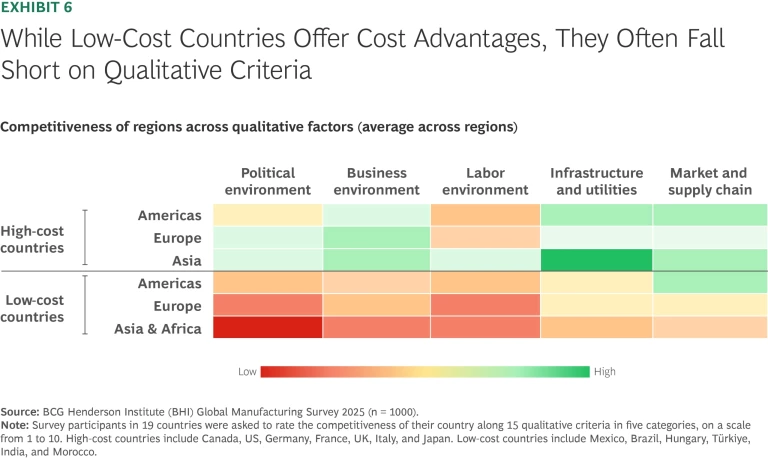

There’s No Universal “Best” Factory Location

Countries perform differently on qualitative criteria, and there is no clear winner that excels across all dimensions. Here, the results are not surprising. In general, low-cost countries have advantages in production costs but often lag on critical qualitative dimensions such as political stability, infrastructure, and highly qualified labor. In contrast, high-cost markets tend to offer greater reliability and ecosystem maturity. (See Exhibit 6.)

But the impact of these findings on decision making is less clear cut. Companies must weigh cost advantages against qualitative gaps, aligning choices with their risk appetite and business model. Ultimately, there is no universal “best” location for production. A country like Germany may seem expensive by cost measures but ranks high on talent, reliability, and ecosystem maturity—making it competitive for firms that prize qualitative factors. For example, US biopharma company Eli Lilly recently started construction on a $2.5 billion factory in Germany (scheduled to open in 2027) to benefit from the country’s pharmaceutical infrastructure and skilled labor.

Similarly, trade-friendly cost hubs like Morocco and the Middle East are becoming attractive alternatives to established “legacy” manufacturing nations that might be more exposed to tariffs. Gotion, a manufacturer of electric vehicle batteries, recently announced that it will build a $1.3 billion factory in Morocco. Lenovo closed a deal in early 2025 with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to build a new manufacturing hub in Riyadh, investing $2 billion and starting production in 2026.

Countries Are at Different Stages in Implementing AI

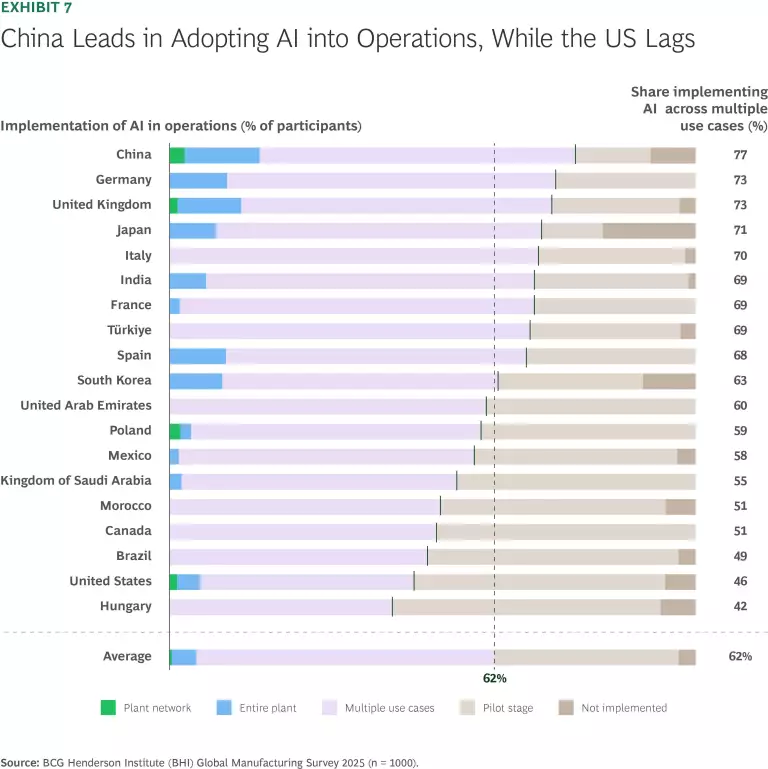

Although most of our survey results relate to the manufacturing network level, several findings within the factory walls are noteworthy—namely the state of AI in operations. Manufacturers see AI as a new source of productivity, but some have struggled to capture the technology’s full potential. Among respondents, 85% recognize the importance of AI in operations, and 62% have implemented more than one AI use case, but just 8% have achieved all targets from their AI initiatives. (See Exhibit 7.)

More surprising is that the US is far behind other advanced economies in terms of AI implementation. China leads in this category, with 77% of respondents saying they now have the technology across their plant network, comprehensively in a single plant, or across multiple use cases. Germany, the UK, and Japan also outperform in terms of AI implementation, potentially because business leaders there see it as a means of closing the cost gap with lower-cost countries. In the US, by contrast, just 46% of manufacturing executives report that level of implementation, ahead of only Hungary.

How Manufacturers Can Respond

Although costs remain the primary challenge for manufacturers in light of geopolitical disruptions, leaders must act to optimize their costs on two levels: network and factory.

At the network level, tariffs can reduce—or in some cases eliminate—the advantages of production in low-cost countries. However, tariffs are also highly unpredictable in terms of both magnitude and duration. For that reason, manufacturers must build stronger scenario-planning capabilities that allow them to weigh quantitative and qualitative criteria carefully across a range of potential future conditions. They should also understand the cost implications of changing the production network.

At the factory level, manufacturers should be relentless about controlling what they can control: costs. That includes increasing productivity within individual factories, for example, through the use of AI and other technologies. These are no-regret moves that will help manufacturers— regardless of the macroeconomic environment.