Nigeria boasts abundant assets—most notably, vast natural resources, arable land, and a young, entrepreneurial population. After a decade of steady growth, promarket reforms, and increased political stability—as demonstrated by a successful democratic change in leadership—the country could be poised to enter a period of sustainable inclusive growth.

But major challenges stand in the way of such progress. Low oil prices have sent the naira plummeting and could lead to a serious economic slowdown. And the country has yet to make meaningful advances against some long-standing problems, including poor governance, corruption, widespread poverty, and inadequate infrastructure.

To understand the actions that could effect real change in Nigeria, we studied the country using The Boston Consulting Group’s Sustainable Economic Development Assessment (SEDA)

On the basis of our SEDA analysis and interviews with Nigerian executives in all key sectors of the economy, including energy, banking, consumer goods, and telecommunications, we propose focused, market-oriented interventions in five critical areas: civil society, governance, infrastructure, education, and health. Infrastructure should be the top priority—weakness there limits progress in a number of other areas, including health and education.

The Economic Challenges

Nigeria, the largest economy in Africa, grew at a compound annual rate of 7.5% from 2000 through 2015. However, Nigerians overall are still very poor—82% of the population lives on less than $2 per day, compared with 26% in South Africa. One factor is the dearth of value-added manufacturing. As a result, there has been little job creation or poverty reduction despite a decade of strong GDP growth.

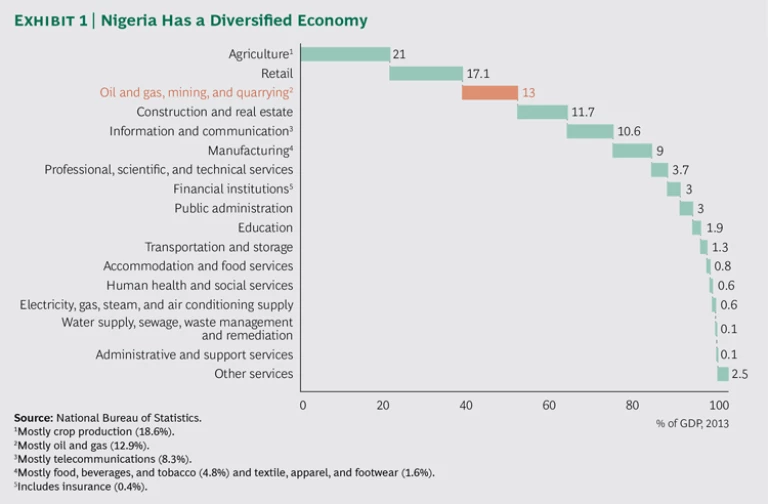

Today, the country's reliance on the oil and gas sector is creating major economic headwinds. Certainly, the domestic economy is quite diversified, with energy representing only 13% of GDP. (See Exhibit 1.) But energy is the only significant export, making it the country's primary source of foreign exchange, and it accounts for 70% of total government income. And falling oil prices are contributing to an economic slump—GDP growth in 2015 slowed to an estimated 2.8%.

SEDA Insights

BCG's SEDA allows us to understand how Nigeria's economic performance affects the lives of the country's citizens. SEDA defines well-being through ten dimensions: income, economic stability, employment, health, education, infrastructure, income equality, civil society, governance, and environment. SEDA examines each dimension along two time frames:

- The current-level score uses the most recent available data to offer a snapshot of well-being on a scale of 0 (the lowest) to 100 (the highest).

- The recent-progress score uses data from the most recent seven-year period for which data is available to examine changes in well-being. This metric also uses a scale of 0 to 100.

SEDA also examines the connection between wealth and well-being through two coefficients:

- The wealth-to-well-being coefficient compares a country’s current level of well-being with the level that would be expected given its GDP per capita (based on purchasing-power parity). The expected level is represented by a coefficient of 1.0, which is based on global averages.

- The growth-to-well-being coefficient compares a country's recent progress in well-being with the level that would be expected given its GDP growth rate. Again, the expected level is represented by a coefficient of 1.0, based on global averages.

In addition to looking at Nigeria's overall performance relative to all the other countries in our data set, we compared Nigeria to three groups:

- Sub-Saharan peers: other sub-Saharan countries with economic and social foundations similar to Nigeria's, including democratic governments, and GDP per capita (based on purchasing-power-parity) of more than $2,000 (Nigeria's is $5,423). Includes Angola, Botswana, Côte d´Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Namibia, South Africa, and Zambia.

- Oil and gas peers: countries that rely heavily on the oil and gas sector, as Nigeria does, and have GDP per capita that is 75% to 225% of Nigeria's. Includes Algeria, Colombia, Ecuador, Egypt, Indonesia, Thailand, Uzbekistan, and Vietnam.

- Aspirational countries: advanced countries with robust recent growth and strong performance in converting wealth into well-being. Includes Brazil, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Poland, and Turkey.

Overall, Nigeria ranks 142nd of the 149 countries in our data set in the ability to convert wealth into well being, just ahead of Libya and Angola and behind Swaziland and Pakistan. The country also trails those in the sub-Saharan peer group—which have many of the same challenges—in this measure.

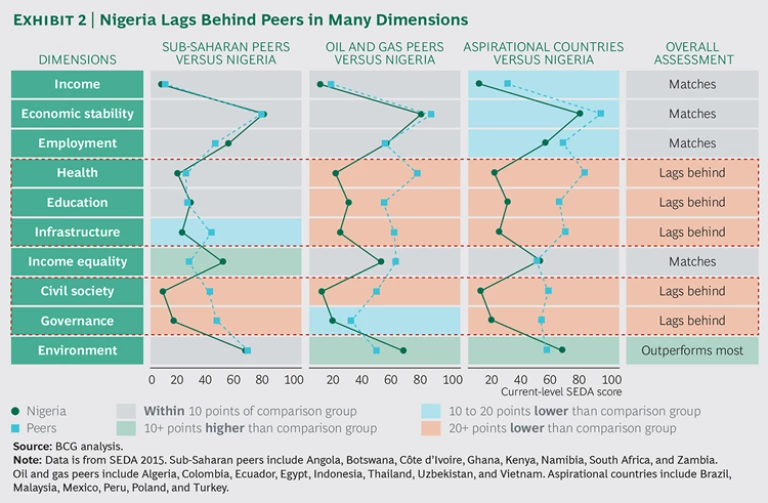

Comparing Nigeria's performance on the ten SEDA dimensions with that of the comparison groups reveals gaps in five areas: governance, civil society, infrastructure, education, and health. (See Exhibit 2.) Certainly, the root causes of Nigeria's challenges in these areas are complex and varied. But in the areas of infrastructure, education, and health, in particular, fragmented governance, poor coordination, and a lack of accountability are major factors.

Strengthening Governance and Civil Society

Our SEDA work shows a strong correlation between governance and civil society. That is hardly surprising: strength in civil society—which includes factors such as civic activism and personal safety—is likely to have a positive impact on some elements of governance, such as political stability and the rule of law.

Improvements in both areas can be challenging to achieve and take years to become evident, but two powerful levers can drive near-term progress:

1. Improve government regulations. The impact of well-crafted and enforceable regulations, particularly those that harness market forces, can be powerful. One potential area for reform is Nigeria's oil subsidy scheme. Currently, the Nigerian government is not making oil subsidy payments, because low oil prices have driven the price Nigerians pay for petrol below the subsidy price. The government should take advantage of this period of low prices to formally end the subsidy system.

2. Deploy digital technologies in government. Digital tools reduce the number of points at which government employees provide services personally or make decisions, cutting down on leakage (the inappropriate diversion of funds through gaps in the system) and enhancing citizens' trust in and engagement with government. The transformation of Nigeria's national pension fund system highlights the power of digital government. Under the old system, it often took years for retired employees to receive their pensions—if they received them at all. The new digital system gives Nigerians increased visibility into and control of their pensions.

Infrastructure: Building the Foundation for Success

Nigeria's anemic infrastructure is in many ways the country's greatest challenge. Only 56% of Nigerians have access to electricity, well below the average of 80% for all three comparison groups. Power outages are widespread, and three-quarters of companies report that the lack of reliable energy is a major constraint. The country's road network is also weak, with 0.21 kilometers of roads per square kilometer, compared with an average of 0.33 for the three comparison groups. And only about 30% of the population has access to "improved sanitation facilities" (those that meet certain hygiene standards), and just 64% has access to drinkable water (compared with an average of 88% for the three groups). These major infrastructure gaps create health challenges and limit job creation and economic diversification.

Studies show that Nigeria will need to invest about $3 trillion in infrastructure over the next 30 years, or roughly $100 billion a year. That is equal to nearly 20% of current GDP annually. The upshot: it will be critical to attract substantial outside investment in the form of public-private partnerships. We recommend five actions for addressing Nigeria's infrastructure crisis:

- Create a central body that is empowered to oversee the life cycle of infrastructure investments. The infrastructure effort must start with the creation of a central governing body with representatives from multiple stakeholders, including state and federal government. This body should appoint an executive group to manage infrastructure projects throughout their life cycle.

- Identify ten high-priority, high-impact projects. The governing body should select ten landmark infrastructure projects that can be executed rapidly in order to generate early wins. The projects should offer a measurable short-term economic boost and long-term positive spillover effects, and, if possible, they should be geographically dispersed.

- Conduct an international road show to line up private funding and establish public-private partnerships

2 2 See the report by BCG and the World Economic Forum <a href="/d/linkresolver/tcm8-133693" title="Strategic Infrastructure: Steps to Prepare and Accelerate Public-Private Partnerships - MA"><em>Strategic Infrastructure: Steps to Prepare and Accelerate Public-Private Partnerships</em></a>, May 2013. . The executive group should take an aggressive role in building connections with private investors. This includes developing a list of potential investors, such as sovereign funds, development finance institutions, and institutional investors. The government should organize a road show to brief investors on the projects. Deals should include some level of sovereign guarantee so that the risk-return tradeoff for investors is adequate but not overly generous. - Focus on flawless execution. The government must develop the skills and talent to ensure excellence throughout a project—from the conception of the idea to the business plan to engineering, design, construction, and maintenance. It must also institute an effective and balanced negotiation process between the private-sector companies that operate the assets and the regulatory bodies that oversee them, guaranteeing full enforcement of tariffs and agreements.

- Leverage momentum to create a sustained infrastructure-building drive. With the ten initial projects under way, the governing body should develop a long-range plan involving another 50 or so projects. Given the dire state of Nigeria's infrastructure, the push for investment must continue for at least a decade.

Education: Bolstering the Workforce

Nigeria trails both the oil and gas peer group and the aspirational countries comparison group in its SEDA education score. Its quality of education score, as measured by the World Economic Forum, has fallen or remained the same for the past four years for which data is available and is below the average for the sub-Saharan peer group. In addition, enrollment rates are low, and armed conflicts in some parts of the country prevent many children from attending school.

Nigeria's education challenges call for smart, well-designed policies. We recommend three critical actions:

- Establish a national curriculum and track results. A standard curriculum should be developed for all Nigerian primary and secondary schools, both public and private. Setting clear, measurable goals and tracking results are crucial. The government must develop objective systems for collecting granular data on performance at the national, state, and individual teacher and student levels, for both public and private institutions. That information should be monitored closely by a review body and should provide the basis for rewards and incentives for top-performing teachers and schools and for teachers working in low-income and rural areas.

- Increase enrollment, bolster the teaching corps, and harness technology and private-sector innovation. The government can boost enrollment by creating financial incentives for low-income families to take their children to school. Initiatives to expand the size and quality of the teaching workforce could include increasing teacher pay and launching a national campaign that trumpets the "Teacher as Nigerian Hero." Technology developed by private-sector players can be a powerful driver of education improvements. The Bridge International Academies, for example, educate more than 100,000 students in over 400 schools in Kenya by creating lessons centrally and distributing them on tablets to teachers. That sort of scalable network can be coupled with high-quality web-based content such as that offered by Khan Academy, a free online education platform.

- Build stronger connections between the education system and the job market. Creating an education system that meets the demands of the job market must entail increasing the supply of workers with vocational and technical training. Government can involve large employers in the development of vocational curricula. And programs should be established to train vocational instructors for both public and private institutions.

Health: A Strategy for Leapfrogging

Nigeria has made progress in health in recent years: from 2000 to 2015, life expectancy increased by eight years, child mortality decreased by 40%, and DTP immunization rates jumped 30 percentage points. But because efforts to improve health issues have tended to be reactive rather than proactive, the country faces serious challenges in a number of critical areas. For example, child and infant mortality rates are still among the highest in the world: 5% of births globally are in Nigeria, but 10% of infant deaths occur there. And life expectancy in Nigeria is just 52 years, compared with 75 years in the group of aspirational countries. In addition, health inequity is a deep-rooted problem, with access and outcomes varying widely in different parts of the country.

Health spending is 5% of the federal budget, far short of the 15% target set by members of the African Union in their 2001 Abuja Declaration. But the bigger issue is the impact—or lack thereof—of the money that is spent. Nigeria can improve its health system through two sets of actions:

Transform the health ecosystem, strengthen the primary health system, and expand health insurance coverage. The initiative should start by addressing the basics. In Nigeria, this means zeroing in on critical issues in the broader health ecosystem, such as sanitation, access to clean water, nutrition, and road and work safety. The country should also develop a system of primary health care centers that focus on disease prevention, early diagnosis, and treatment, thus easing the pressure on crowded hospitals. Such a system can make a big difference in maternal and child populations and in addressing the management of increasingly common noncommunicable diseases such as diabetes. Nigeria must also expand health insurance coverage, potentially through a vibrant health insurance market. This will help alleviate health inequities and lower the often catastrophic out-of-pocket costs for patients, making them more likely to seek preventive or early treatment.

- Take steps to allow Nigeria to leapfrog in the development of the health system. The government should focus on improving the infrastructure, investment environment, skills, and regulations that will allow Nigeria's health system to leapfrog, or skip one or more traditional development stages. The first step is to embrace innovative technological solutions. This includes deploying telemedicine technology and mobile health units in order to expand access to health services cost effectively. Second, the country should train more nurses and frontline community health workers and promote the shifting of tasks from physicians to these other workers. Third, Nigeria should tap its vibrant private sector to strengthen the health system by, among other things, accelerating the development of the nascent insurance market. Focused efforts to drive leapfrogging in health are already producing tangible results in Nigeria's Ogun State.

Getting It Done

Making meaningful progress can be particularly daunting in developing countries like Nigeria, where there are constraints such as a lack of expertise in project implementation, patchy or ambiguous laws and weak enforcement, and a lack of accountability among ministries and agencies. In Nigeria, the challenges are compounded by the federal system, in which policies and plans are developed at the federal level but need to be implemented at the state level.

With those issues in mind, we have identified eight actions that are critical to ensuring maximum impact.

- Set clear priorities, move quickly, and keep it simple. Leaders can squander their political capital by taking on too many projects at once. Instead, it makes sense to focus on a few significant problems and show results quickly.

- Focus resources on those priorities. Once priorities are established, leaders should direct their best teams as well as their financial resources and budgets toward those goals.

- Develop detailed action plans and monitor execution closely. This means establishing rigorous plans with specific targets and milestones, clarifying responsibilities, and monitoring progress.

- Create links between implementers and decision makers. People leading change efforts need to report directly and have access to decision makers. In Nigeria, these links must be forged within the states and the federal government, and between the two levels.

- Lead from the front. This requires being hands-on while inspiring and empowering people.

- Go for early wins—but keep an eye on the long term. Some initial, well-publicized successes are critical to creating momentum for reform. But leaders should keep in mind that the most successful long-term solutions generally develop over time, through learning and adaptation.

- Communicate, communicate, communicate. Leaders of reform need to make sure that their message is clear and unequivocal, and is communicated effectively to government workers and private citizens.

- Leverage partnerships. The government needs to develop strategic partnerships with the private sector, donor organizations, and development finance institutions.

Addressing the current economic challenges in Nigeria and unleashing the energy and drive of its people will require action by the government—most notably in infrastructure, health, and education. Improvements in those areas will create sizable, positive ripple effects throughout the economy, including possibly a surge in foreign direct investment. Focused and sustained effort can yield real progress—and raise the well-being of all Nigerians.