The 2019 M&A Report examines how dealmakers should think about M&A activity in a downturn. Our recommendations are based on a study of the returns of dealmaking throughout the economic cycle. Simply put, our research shows that downturns can be excellent times for dealmaking. But success requires careful preparation, thorough execution, and, especially, bold decision making.

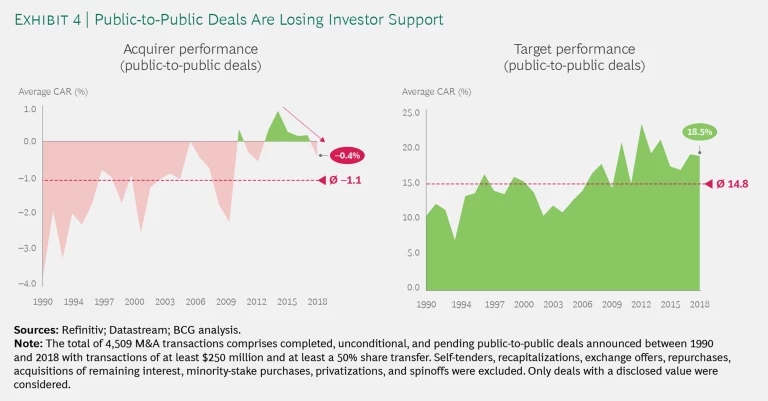

2018 might be remembered as the year that foreshadowed more challenging times ahead for dealmakers. The year got off to a strong start, but overall M&A activity fell sharply over the course of the year. Dealmakers coped with increased volatility in equity markets, decreasing valuations, and macroeconomic and political uncertainty. This turmoil carried over into the first half of 2019 and affected dealmaking around the world. Perhaps most alarming, for the first time since 2011, cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) were negative for acquirers of public targets—an indication that investor sentiment toward M&A is returning to the historical norm.

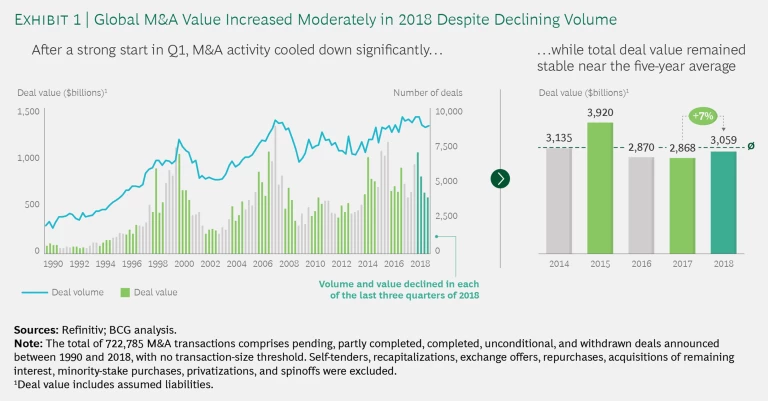

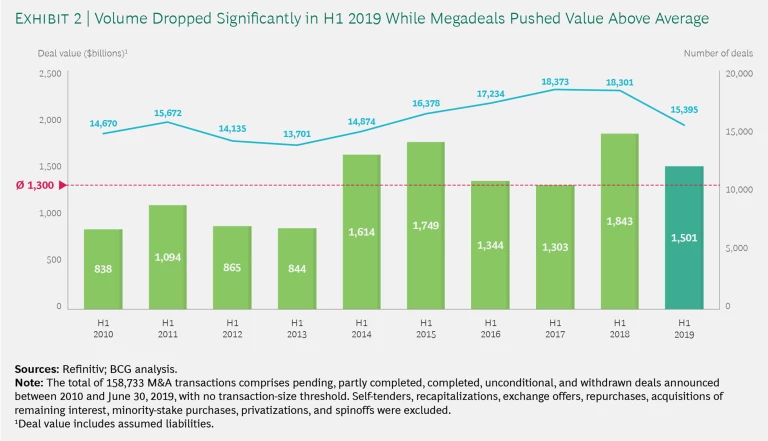

The net result for 2018, though, was a largely stable year in which global M&A value increased moderately despite declining volume. A 7% uptick left the global value near the five-year average. But after a strong first quarter, deal value declined steadily throughout the rest of the year. The fast start was attributable to a flood of megadeals (deals valued at $10 billion or more)—17 in the first three months versus 14 thereafter. In the first half of 2019, M&A value stabilized near the long-term average while volume dropped significantly. The rebound in value was propelled by strong levels of North American dealmaking, supported by several megadeals, especially in the second quarter.

What will happen next? Several trends are likely to promote M&A activity. Corporations have ramped up sell-side activities, in some cases seeking to placate activist investors. Similarly, private equity firms are exiting investments to cash in on the returns achieved in the recent positive environment. At the same time, high levels of liquidity and low interest rates are motivating buy-side activities. In many industries, digitization and the emergence of new business models are driving M&A-enabled transformations.

So far, so good. But the wild card here is the macroeconomic environment. Through several years of persistent political uncertainty and market volatility, the M&A market has remained resilient. Today, however, dealmakers must come to terms with the fact that the global economy is most likely in the later stages of the cycle. Trade wars, Brexit, weakness in China’s economy, forecasts of slower growth, and ominous leading economic indicators are among the issues weighing down sentiment in capital markets. With storm clouds building, what can forward-looking dealmakers do to get ready for a recession?

We analyzed a unique data set totaling more than 51,600 deals made over the past 40 years that met our study criteria (out of our total M&A database of more than 750,000 deals). We found that, two years after a transaction, deals made in a weak economy created more value for buyers than those made in a strong economy. Boldness pays off—the outperformance is largely driven by acquisitions outside the buyer’s core business segments. And, although occasional buyers create value through acquisitions in weak economies, experienced buyers outperform by a wide margin.

To prepare for dealmaking in a downturn, a company must carefully assess which types of acquisitions will set the foundation for strong growth in the recovery. To emulate experienced dealmakers, it must build the capabilities required to identify critical assets—both within and outside its core business segments—as well as those needed to execute transactions and integrate new businesses effectively.

Global M&A Activity Takes A Breather

Taken as a whole, 2018 continued the streak of good years for M&A activity dating back to 2014. Global M&A value increased by about 7%, which is close to the five-year average. Deal volume declined slightly (by 3%), with about 35,800 deals announced during the year. (See Exhibit 1.)

But the annual figures mask a significant development: both deal value and volume declined sharply in the second half of the year. The first quarter of 2018 was especially strong. The number of megadeals (those valued at $10 billion or higher) announced in the first three months soared to 17, compared with a quarterly average of six in each of the previous ten years. In contrast, only 14 megadeals were announced in the remainder of 2018. The slowdown in the second half of the year can be blamed on a number of factors, including increased volatility in equity markets, decreasing valuations, and macroeconomic uncertainty.

The 2019 M&A Report

The 2019 M&A Report

- Downturns Are a Better Time for Deal Hunting

- Dealmakers Do Well in Downturns

- How to Master M&A in a Downturn

Europe and North America drove the global increase in deal value in 2018 with growth rates of 7% and 5%, respectively. Deal volume declined in all regions. Europe (–11%) and North America (–13%) were largely responsible for the overall global decline.

The value of global cross-border M&A grew by 45% in 2018, while volume followed the overall trend and declined by 6%. The same trend was seen, to varying degrees, on a regional level. Most notably, compared with the peak reached in 2016, outbound M&A from China experienced sharp reversals in both value (–78%) and volume (–31%).

In 2018, some industries posted increases in deal value, owing to outlier effects from a few large deals. However, nearly every industry saw a decline in overall M&A volume. The leader in deal value was the media and entertainment sector, with a 42% increase in 2018 (although volume was actually down by 4%) resulting from large-scale industry consolidation. Two noteworthy deals were US cable company Comcast’s $40 billion bid for Sky and Vodafone’s $22 billion acquisition of German cable operator Unitymedia. The health care industry posted the second-biggest increase, driven by large-scale deals such as the $60 billion takeover of UK-based biopharmaceutical specialist Shire by Takeda, Asia’s largest pharmaceutical company.

Alarming Trends Persisted in the First Half of 2019

In the first half of 2019, M&A value stabilized near the long-term average. However, some alarming trends persisted. M&A volume dropped to 15,400 deals, approximately 3,000 fewer than in the first half of 2018—possibly indicating an end to the current M&A cycle. (See Exhibit 2.)

The rebound in deal value was propelled largely by megadeal activity in North America, especially in the second quarter. Among the 21 megadeals announced in the first half of 2019, the following were the top five in value:

- United Technologies’ bid for Raytheon ($87 billion)

- Bristol-Myers Squibb’s takeover of rival drug maker Celgene ($79 billion)

- Saudi Aramco’s majority-stake acquisition of petrochemicals group Sabic ($69 billion)

- AbbVie’s bid for Allergan ($62 billion)

- Occidental Petroleum Corporation’s outbidding of Chevron for Anadarko ($38 billion)

Comparing the first half of 2019 with the first half of 2018, deal value declined sharply in Europe (–60%) and Asia-Pacific (–45%). Only North America saw an uptick in deal value (16%), with US megadeals fueling the global rebound in M&A. Each of these regions saw relative declines in deal volume. The sharpest decline occurred in North America (–22%).

The first half of 2019 brought relatively few announced cross-border megadeals, possibly because of increased trade tensions and other geopolitical factors. Newmont Mining Corporation, a US company, acquired Goldcorp, a Canadian competitor, in a stock-for-stock transaction valued at $10 billion. Barrick Gold Corp’s hostile takeover offer for Newmont Mining, valued at about $23 billion, was announced in the first half of 2019 as well, but later withdrawn.

Most industries experienced a decline in deal value compared with the first half of 2018. However, two industries stood out with double-digit increases (partly driven by larger deals on average): energy and power (11.2%) and industrial companies (22.6%). For example, among industrial companies, United Technologies’ bid for Raytheon was responsible for a significant increase in the deal value of acquisitions of aerospace and defense companies. Deal value also increased in high tech (2.8%) and health care (6.1%). All industries saw a decline in deal volume compared with the first half of 2018.

Buyers of Public Targets Lose Investor Support

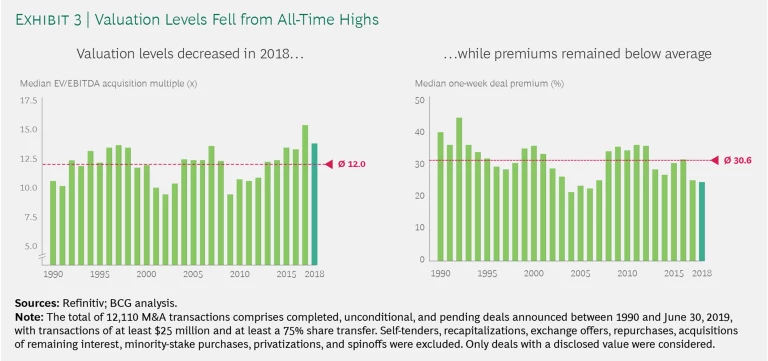

In terms of valuation, deal multiples—enterprise value divided by EBITDA—declined slightly in 2018, to a median of 13.7x. In the first half of 2019, multiples declined further to 13x. That is lower than the all-time high of 15x set in 2017 but still above the long-term average of 12x. The continued decline in the first half of 2019 was driven, in part, by decreasing multiples in cyclical industries, such as industrial companies and consumer-related businesses. However, the average multiple paid for high-tech companies increased significantly. Acquisition premiums, on average, held steady (24.1% in 2018 versus 24.6% in 2017). In the first half of 2019, they rose to 31.2%—slightly above the long-term average of 30.6%. (See Exhibit 3.)

The past ten years have been relatively good times for dealmakers. Our analysis shows that, from 2009 through 2018, about half of all public-to-public M&A deals created value in terms of announcement returns and longer-term performance. For previous time periods, research and studies (including our own) have typically found that significantly less than half of deals achieve such success.

Traditionally, investors have reacted to the announcement of a public-to-public deal by pricing the target’s shares somewhere near the bid price, while the acquirer’s stock fell on concerns of earnings dilution, poor fit, excessive diversification, or some other factor. From 2012 through 2017, however, cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) of both targets and acquirers were positive, indicating that investors were placing their bets on dealmakers.

In what may be a sign of more difficult times ahead for acquirers, 2018 saw a reversal of the recent trend. As shown in Exhibit 4, acquirers’ CARs centered on the announcement date fell to an average of –0.4%. Although it is well above the historical (since 1990) average of –1.1%, this negative figure indicates that investors are growing skeptical about companies’ ability to create value by acquiring public targets. Targets saw their CARs dip slightly to 18.5% in 2018, still above the average of 14.8%.

The shift in investor sentiment toward acquirers is attributable to several factors. With concerns mounting that a downturn may be near, shareholders are losing their appetite for risk and are scrutinizing more carefully an acquisition’s potential to create value. This is consistent with our finding in the 2018 M&A Report that investors have become more skeptical about buyers’ ability to deliver on the bold promises in their synergy announcements.

A review of several deals announced in the first half of 2019 demonstrates that investors are more carefully scrutinizing acquisitions’ potential to create value. On the positive side for dealmakers, Danaher’s stock jumped 8.5% after it agreed to buy General Electric’s life sciences unit for $21 billion. Shares in BB&T rose 4.5% after the company announced its $28 billion merger with SunTrust. And investors welcomed logistics player DSV’s acquisition of its competitor Panalpina, pushing shares higher by almost 6% on the day of the announcement.

But such positive reactions are no longer the norm. Bristol-Myers Squibb’s shares plummeted 15% after the company announced a deal to acquire Celgene for $90 billion. Although some shareholders (especially the activist investor Starboard Value) wanted to stop the deal, it ultimately received shareholder approval. Two large financial data and technology deals—FIS’s takeover of Worldpay for $43 billion and Fiserv’s acquisition of First Data for $39 billion—similarly resulted in sharp drops in the acquirer’s stock after the announcement. In the tech sector,

Salesforce’s shares dropped by more than 5% in reaction to an announced deal to acquire Tableau Software for $17 billion. European investors are increasingly skeptical about M&A moves. For example, Sunrise Communications Group’s stock price declined by more than 8% after it announced the acquisition of UPC Switzerland, a Switzerland-based cable operator, from Liberty Global.

Four Major Trends

Where does the M&A market go from here? The market is being shaped by trends that influence both the sell side and the buy side, as well as by topics affecting the broader business environment.

Corporate divestitures and spinoffs, as well as private equity exits, support supply. Divestitures by corporations and private equity (PE) firms are on the rise, as these organizations seek to cash in on high valuations or sell assets that are at risk of underperforming before the next recession.

Although the volume of corporate divestitures fell slightly in 2018, total deal value rebounded to near the recent highs reached in 2014 and 2015. Some of the selling has been in response to, or in anticipation of, activists’ demands. The need to address antitrust concerns in the merger-approval process, especially for megadeals, has also fueled sell-side activity. The volume and value of PE exits are also slightly off their peaks of 2017, though still at moderate to high levels.

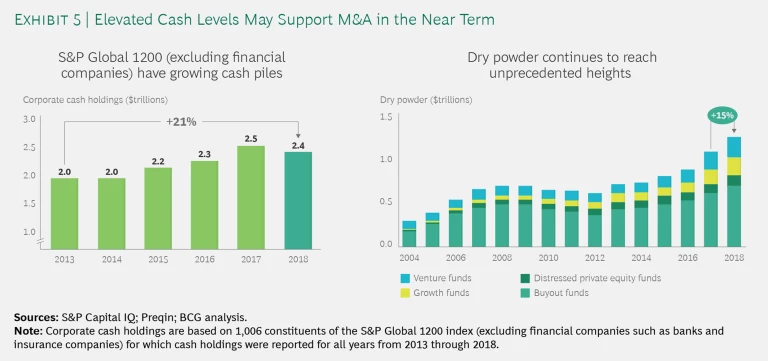

High cash levels drive demand. Elevated levels of cash holdings, for both corporations and PE firms, will continue to support dealmaking in the near term. Among the S&P Global 1200 (excluding financial institutions and insurance companies), cash holdings totaled $2.4 trillion in 2018, down slightly from 2017 but still 21% above the level in 2013. Over the medium term, the fact that corporate cash holdings appear to have peaked may mean that some companies will choose to forgo M&A activity and instead hold onto their cash in anticipation of an economic downturn. Among PE firms, reserves of dry powder increased by 15%, up by a staggering 74% since 2013 and continuing the streak of annual records. (See Exhibit 5.)

Assets under management by activist investors reached $384 billion in 2018, a 34% increase since 2013. Activists’ interventions, whether actual or feared, serve as a catalyst for dealmaking and divestitures.

In addition, the interest rate environment is still favorable for dealmaking. Central banks plan on keeping rates low for an extended period and are even considering new rounds of rate reductions. There are nuances, however. While yields in Europe and Japan are still close to historic lows, yields for corporate bonds have recovered a bit in response to quantitative tightening in the US last year. However, it remains to be seen how the July interest rate cut by the US Federal Reserve will affect capital markets in the coming months.

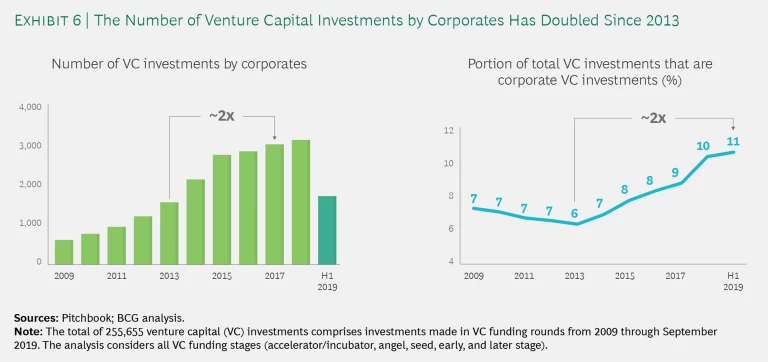

Industry convergence and the rise of ecosystems encourage unconventional deals. The absolute number of venture capital (VC) investments by corporate investors and the relative share in all VC investments (by volume) has doubled since 2013. (See Exhibit 6.) Increasingly, the objective of deals is not to take control of a company but rather to gain access to specific capabilities, talent, or technology or to establish partnerships. Two related developments are promoting the shift in emphasis.

First, the increasing prevalence of tech-enabled business models is blurring the boundaries between industries and leading to the convergence of previously distinct business sectors. For example, the distinction between mobility companies and technology companies has blurred, as ride-hailing apps (such as Uber, Lyft, and Didi) and developers of self-driving vehicles (such as Waymo, a subsidiary of Alphabet) enter the sphere of automakers and other traditional mobility players. Similarly, traditional banks and insurers face increased competition from “fintechs” and “insurtechs” as well as digital payment providers. Industry convergence is also occurring between the telecommunications and media industries, as evidenced by AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner.

Second, as companies increasingly integrate technology into their products and services, complex ecosystems are emerging throughout the business landscape and across industries. To bring together all the required elements of technology-enabled offerings, companies must work with a far wider range of partners than in the past. Traditional bilateral partnerships within a single industry are giving way to multilateral cross-industry partnerships, potentially involving dozens of players. Because such ecosystems are fluid and dynamic, and not perfectly controllable, dealmakers will need to utilize a wider range of deal types and consider different depths of integration.

These two developments are giving rise to more cross-industry transactions. In this context, nontraditional deals—including joint ventures and alliances, corporate venture capital investments, and the purchase of minority stakes—are gaining importance. Several recent announcements illustrate the growing role of alliances:

- In January 2018, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JPMorgan Chase announced that they would form an independent health care company to provide services to their employees in the US.

- In September 2018, Netflix and numerous camera equipment, editing, color correction, and encoding companies created the Post Technology Alliance. The objective is to ensure that participating companies’ products comply with Netflix’s content specifications.

- In May 2019, Toyota participated in a funding round for Uber’s self-driving car unit, Uber Advanced Technologies. Other participants included Softbank’s Vision Fund and automotive components manufacturer Denso.

- Some companies are beginning to build their entire business around ecosystems. For example, Japan’s Softbank Group is building a comprehensive system of subsidiaries and making other investments in sectors such as telecommunications and technology.

To succeed in nontraditional transactions, dealmakers need new skills related to scouting and negotiation. Post-deal collaboration, governance, and integration efforts are also getting more complex.

Resilience supports M&A activity. In recent years, dealmakers have generally shrugged off the political and economic uncertainty. This runs counter to the historical trend in which deal volume declined as uncertainty increased (as measured by the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index). However, the cooldown in the second half of 2018 showed that dealmakers will not maintain a “keep calm and carry on” mindset indefinitely. Even in recent years, deal volume has slumped in response to market volatility (as measured by the VIX Index).

The overall resilience of the M&A market reflects the fact that dealmakers focus more on the fundamentals of the macroeconomic environment (such as economic growth, forecasts, and megatrends) than on the latest headlines or market gyrations. Despite a multitude of risks—including Brexit, trade wars, the slowdown of China’s economy, and fraying international alliances—these fundamentals have remained strong enough to support a healthy level of M&A activity.

However, the arrival of the next recession is a matter of when, not if. A global economic downturn will eventually occur—whether triggered by a specific shock or the long-overdue end of the current recovery. Recent downward revisions in the GDP growth forecasts for many regions and countries, as well as generally declining growth rates, could be the first indicators of a looming downturn. When the recession arrives, should dealmakers pull back from their core pursuit? Our research indicates that the answer is no. In fact, pursuing M&A deals during an economic downturn can create value for buyers, as we discuss in the related article from the 2019 M&A report, “The 2019 M&A Report: Dealmakers Do Well in Downturns.”