Yesterday, the CO2 concentration at Baring Head near Wellington was 415 parts per million – the highest recorded ever in New Zealand. At a CO2 concentration of 430 parts per million, global warming of 1.5°C is forecast to occur.

Reflecting the gravity and speed of climate change, New Zealand has committed to meaningful action and is relatively well-placed to rapidly decarbonise its economy. We have analysed New Zealand’s emissions profile and ambitious transition plans to identify ten ways New Zealand can accelerate this transition.

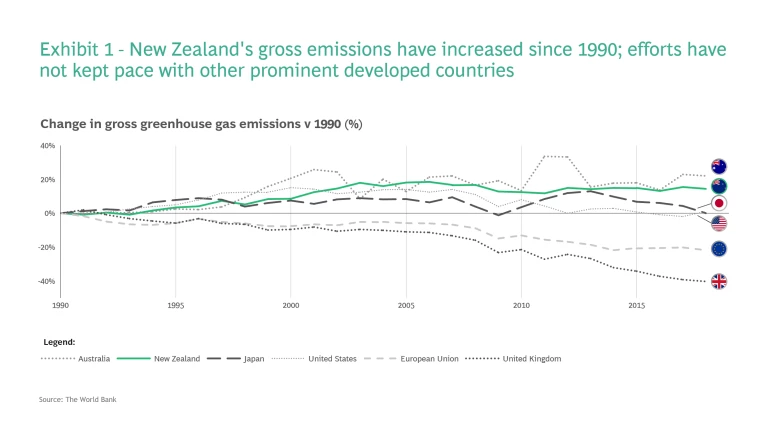

This action is needed because New Zealand’s greenhouse gas emissions have increased by 14% since 1990, in contrast to its clean, green, and 100% pure image. By comparison, emissions have decreased by 22% across the European Union and 40% in the United Kingdom over the same period.

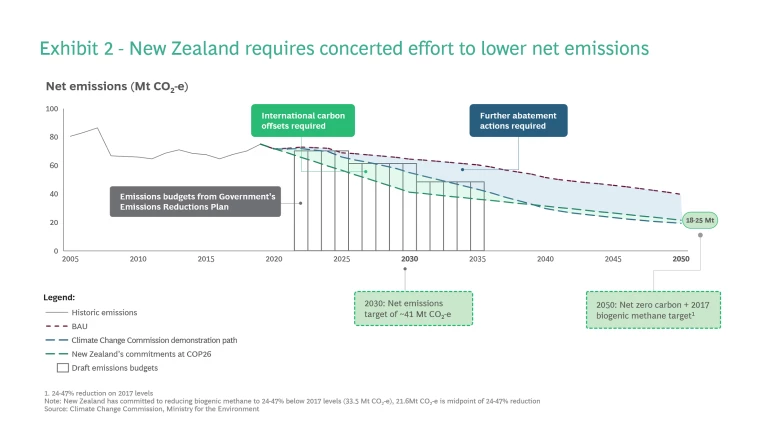

New Zealand has committed to reducing net emissions (gross emissions minus new carbon absorbing activity, such as trees planted) in half by 2030 from a 2005 gross emissions baseline, and achieving net zero emissions by 2050. Both targets exclude biogenic methane which has its own reduction targets of 10% by 2030, and 24-47% by 2050, both from a 2017 baseline.

To reach these targets, the Government recently set emissions budgets to 2035, as part of its Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP). The ERP also outlines a number of actions targeting emissions reductions over the next five years. Our analysis of the Climate Change Commission's Demonstration Path identifies that a cumulative 430 Mt CO2-e (megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent) of domestic emissions abatement is needed by 2050 to achieve our targets (see the blue area in Exhibit 2). A further cumulative 100 Mt CO2-e of international offsets likely need to be purchased through to 2037 (see the green area in Exhibit 2).

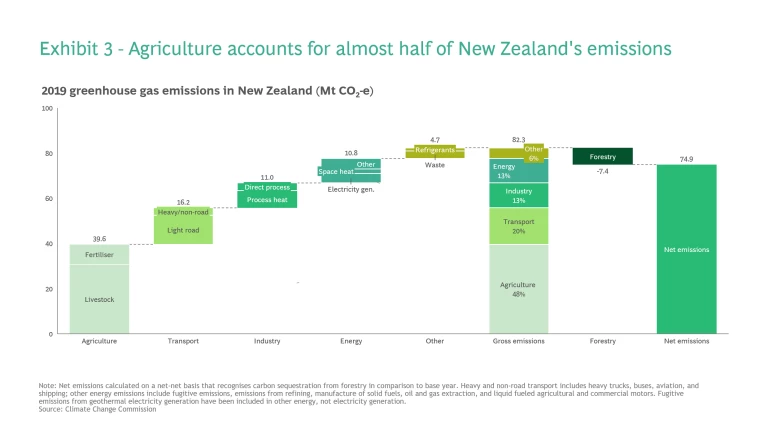

To determine our ten climate actions, we split New Zealand’s emissions profile into six categories [Exhibit 3]:

- Agriculture accounts for 48% of emissions today, primarily methane from livestock and nitrous oxide from fertiliser in the dairy and meat industries

- Transport accounts for 20% of emissions, primarily from cars and trucks

- Industry accounts for 13% of emissions, primarily from process heat for manufacturing

- Energy accounts for 13% of emissions, primarily from heating buildings and generating electricity

- Other sources of emissions account for the remaining 6%, mostly refrigerants and the disposal of waste

- Forestry accounts for a 8% reduction in gross emissions, removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere

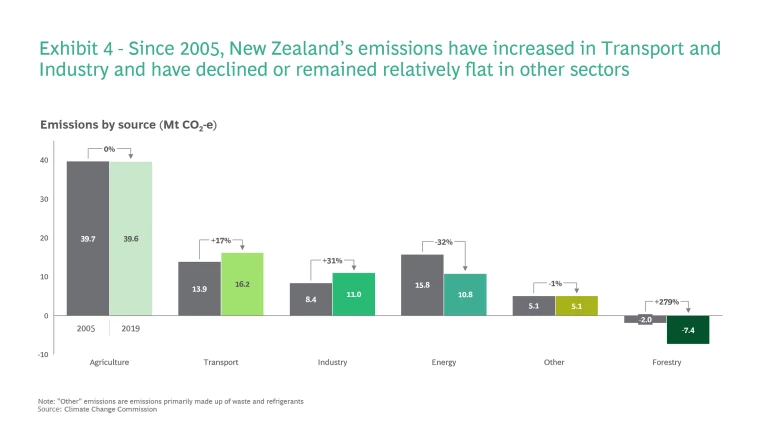

Between 2005 and 2019, transport emissions increased by 17% and industry emissions by 31%. Energy sector emissions reduced by 32%, driven largely by reduction efforts in the sector; emissions sequestered through forestry increased significantly [Exhibit 4].

Ten actions to accelerate New Zealand’s net zero transition

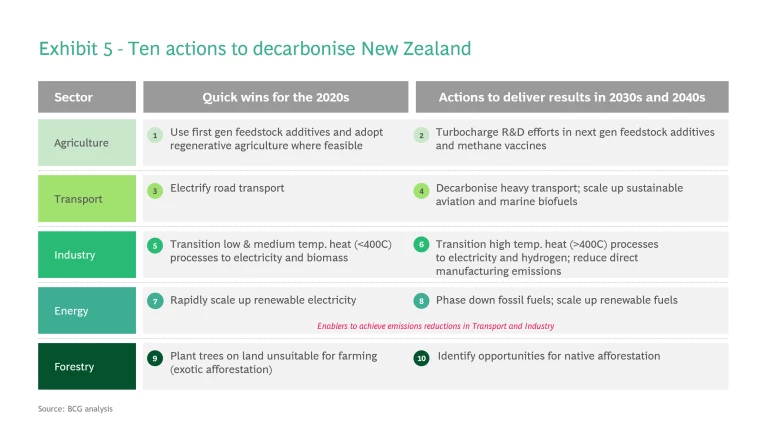

We believe New Zealand should take ten actions to accelerate the transition to net zero. Five of these actions will deliver material emissions reductions from the 2020s onwards, while the other five actions, provided the foundations are laid in the 2020s, can significantly reduce emissions in the 2030s and 2040s [Exhibit 5].

1. Agriculture: Use first-gen feedstock additives and adopt regenerative agriculture where feasible

2. Agriculture: Turbocharge (R&D) efforts in next-gen feedstock additives and methane vaccines

3. Transport: Electrify road transport

4. Transport: Decarbonise heavy transport; scale sustainable aviation fuels and marine biofuels

5. Industry: Transition low and medium-temperature heat (below 400°C) processes to electricity and biomass

6. Industry: Transition high-temperature heat (above 400°C) processes to electricity and hydrogen; reduce direct manufacturing emissions

7. Energy: Rapidly scale renewable electricity

8. Energy: Phase down fossil fuels; scale renewable fuels

9. Forestry: Plant trees on land unsuitable for farming (exotic afforestation)

10. Forestry: Identify opportunities for native afforestation

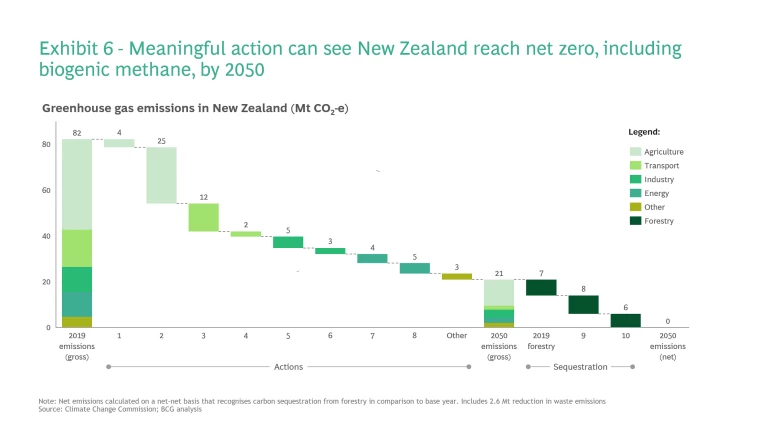

In total, these actions can reduce New Zealand’s gross emissions by 75% in 2050, from a 2019 baseline [Exhibit 6]. The remaining 21 Mt CO2-e emitted annually could be offset through further afforestation, bringing New Zealand to net zero across all greenhouse gases by 2050 – including biogenic methane, which is an improvement on the Government’s target.

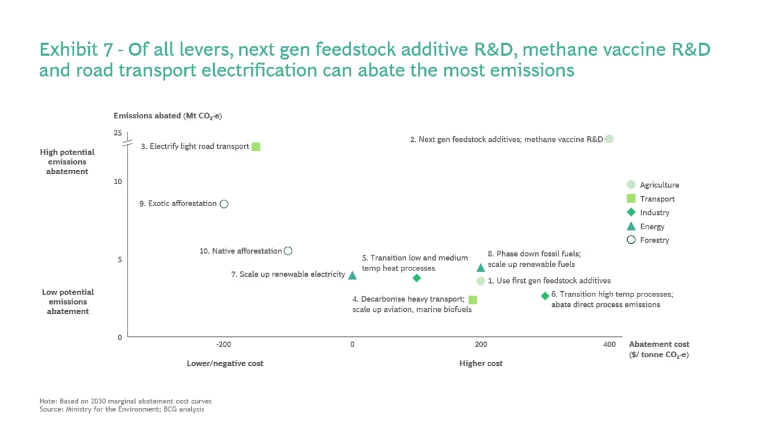

In Exhibit 7, we have evaluated the emissions abatement potential and marginal cost per tonne of CO2-e for our ten actions. In the near term, electrifying light road transport (#3), exotic afforestation (#9 and #10), scaling up renewable electricity (#7) and transitioning low and medium temperature processes (#5) are the quickest wins with the lowest marginal abatement costs. In the longer-term, next-gen feedstock additives and methane vaccines (#2) offer the greatest potential for reducing gross emissions. While the associated marginal abatement costs are forecast to be high in 2030 (~$400/tonne CO2-e), investment in R&D could reduce these costs significantly.

Achieving net zero inclusive of biogenic methane requires a concerted effort from the public sector, the private sector, and communities across the country. While there is a lot of work to do, there is also a lot of potential. Action on climate change could be a source of great competitive advantage for New Zealand, through world-leading agricultural emissions reduction technology exports, ultra-low carbon food production, sustainable tourism, renewable energy, and clean industry.

This analysis only scratches the surface of this dynamic and complex issue. We welcome the opportunity to discuss how your company can succeed while contributing to New Zealand’s emissions reduction efforts. If you are interested in BCG’s climate change and sustainability work in New Zealand, reach out to one of our authors.

The authors would like to thank the following colleagues for their support and assistance: Janelle Cook, Anna Leonedas, James Meland, Matthew Santos, Paul Sutherland, Chris Wheeler, and Liz Zhu.