In a port city, dock workers unloading ships are paid partly in cash; then they give back a quarter of it to their boss. At the end of the month, some goods aren’t recorded. Some apartment owners in the city don’t pay taxes on them.

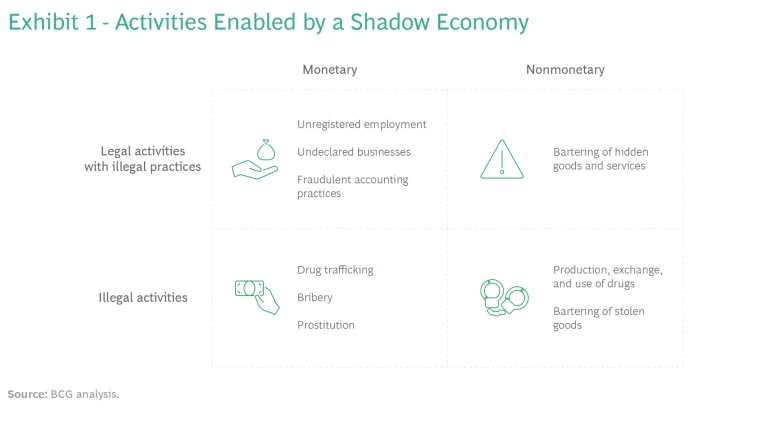

This so-called “shadow economy”—also known as the black market or the informal or underground economy—is the body of economic activities operating without official government regulation or record keeping and deliberately concealed from regulatory authorities. In practice, these activities encompass a broad spectrum of misconduct. Some are illegal: the production and exchange of illicit goods, or transactions such as extortion and bribery. Others include commonplace everyday events like providing unreported cash payments to employees or exchanging goods and services informally. These transactions exist in a legal gray area, falling outside the realm of established laws, and are typically not subject to government regulations, taxation, or surveillance.

Some form of shadow economy is thus inevitably present in most societies. Often, marginalized communities and small businesses depend on it as a source of jobs and income. The formal economy also often interacts with it directly. Economic research and observation from the past two decades, including IMF studies, have found that about two-thirds of money spent through the shadow economy is immediately circulated back to more conventional transactions like retail store purchases, thus providing an ongoing stimulus to the formal economy.

Governments are increasingly recognizing the need to constrain the shadow economy given its connection to issues such as loss of tax revenues, reduced productivity, and threat to national security. However, because these economic activities are so well concealed, it is often a struggle to identify them, track their extent, and address this issue effectively. Managing the shadow economy is crucial for governments seeking to uphold transparency, accountability, and public trust while promoting overall societal well-being in the economic landscape.

Hidden Harmful Effects

Institutions such as the IMF and the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) have identified many harmful effects of the shadow economy. There are seven broad categories of concern:

- Tax Revenue Loss. Unreported income and transactions lead to lower tax revenues, impeding the government’s ability to fund public services and essential infrastructure.

- Reduced Productivity. Many activities within the shadow economy operate without proper legal recognition or registration. These activities thus miss out on the benefits formal sectors offer, such as access to financing and government grants, which play a crucial role in enhancing productivity by enabling the development of skills and technology.

- Lack of Employee Protection. Workers engaged in the shadow economy typically lack legal protections such as minimum wages, safety standards, and social security benefits, exposing them to the risks of exploitation and unfair treatment.

- Unfair Competition. Without conventional taxes and regulation, informal businesses have an unfair advantage over formally registered companies, resulting in skewed competition.

- Distortion of Economic Indicators. A significant shadow economy can distort official economic indicators and statistics, which are crucial for policymaking, economic planning, and assessing the country’s overall economic health.

- Undermined Institutional Confidence. A widespread shadow economy signifies a general lack of fairness, transparency, and effective governance. This can erode public trust, as the government is seen as less able to manage the economy and the nation.

- National Security and Crime. The underground economy is used for criminal activity, including money laundering, tax evasion, and the funding of terrorism. This poses significant risks to national security.

All shadow economy activities are considered illegal due to their concealment from authorities. However, in practice, these activities encompass a broad spectrum of misconduct. (See Exhibit 1).

Underlying Causes

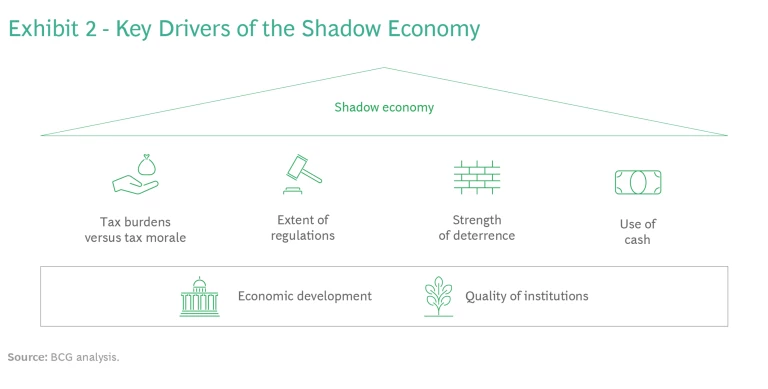

Exhibit 2 shows the six key drivers of the shadow economy, organized according to the way they bolster one another’s influence. Every country has its own mix of these factors, and this framework can be used to decide how to focus a government’s efforts.

Economic Development. The most sweeping underlying factor is the level of economic development. This refers to a nation’s progress in enhancing living standards, reducing poverty, and promoting overall well-being.

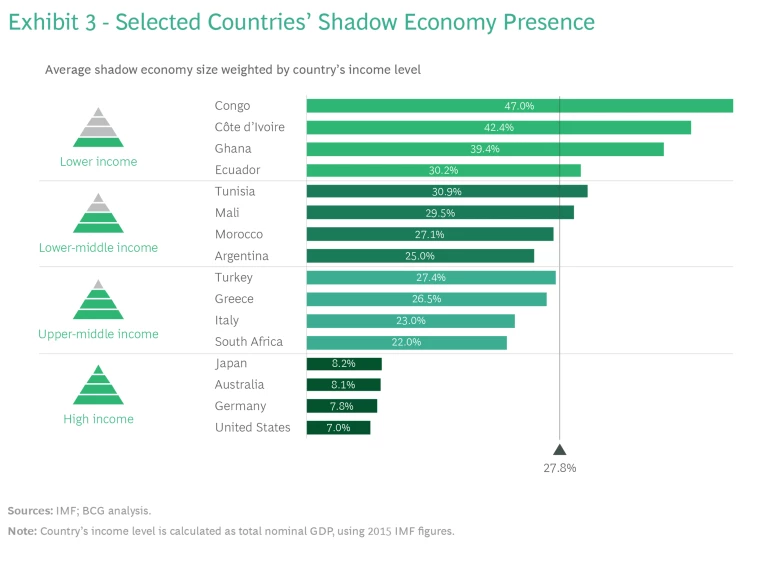

BCG analysis, based on IMF data covering more than 150 countries, has found that, on average, countries with lower GDP per capita have larger shadow economies—typically accounting for more than 30% of GDP per capita. In these countries, high poverty and unemployment rates, along with endemic income inequality, impose financial difficulties on low-income individuals, who turn to the shadow economy for their livelihood. By contrast, higher-income countries have shadow economies that hover at around 7% to 8% of the formal GDP per capita. (See Exhibit 3.)

Quality of Institutions. Another underlying factor is the quality of a country’s institutions. Research studies demonstrate that there is a negative correlation between the Transparency International corruption index and the size of shadow economy across countries. This is because when government agencies lack transparency or tolerate corruption, public trust in them erodes. Individuals are thus more skeptical of government in general and more prone to engage in informal economic activities, such as working without proper permits or evading taxes. They believe that their tax contributions would be misused and also that tax evasion will be unnoticed or unpunished. On the other hand, when people trust government institutions, they are more likely to pay taxes and use public services.

Tax Burdens Versus Tax Morale. Low economic development and poor institutional quality support four other crucial drivers for the shadow economy. A country’s tax burden, including income, sales, property taxes, and social security contributions, along with other levies imposed by the government, influences peoples’ behavior and economic decisions. When the following two conditions are in place—taxes are excessively high, and governments offer little in the way of benefits—individuals or businesses may turn to informal economic practices like off-the-books transactions to minimize their tax liabilities and increase their take-home income.

The felt impact of the tax burden can be reduced through robust tax morale. Global macroeconomic research shows that when people have higher trust (as reflected by their affirmative responses to the World Values Survey question regarding whether they believe most people can be trusted, using a binary scale), tax collection increases. This is because when people believe that their tax money is being used to benefit the community and that they will receive quality services in return, they move away from shadow economies. For instance, Scandinavian nations impose substantial tax rates but tend to have smaller shadow economies, while other countries, even when they have lower tax rates, grapple with larger shadow economies.

Extent of Regulations. Burdensome regulations on the labor market, businesses, and trade lead to a larger shadow economy, since they typically increase the cost of doing business and wages. For instance, countries that enforce stringent regulations on particular businesses create incentives for business owners to circumvent the rules by operating unregistered businesses or submitting inaccurate information.

Moreover, stringent regulations introduce administrative burdens. They require regular reporting, meticulous record keeping, and compliance verification. Intricate bureaucratic procedures, extensive paperwork, and lengthy approval processes only amplify these effects and can further deter enterprises from engaging in formal sector activities.

Strength of Deterrence. The size of the shadow economy is strongly linked to the perceived likelihood of being caught, the severity of penalties and fines upon discovery, and the level of public awareness. In the US, the Internal Revenue Service employs advanced monitoring and detection mechanisms such as advanced data analytics, matching programs, and information sharing with other government agencies to identify instances of tax evasion and unreported income. People know there is a high likelihood of being caught, and the penalties for tax evasion can be substantial. This strength of deterrence is one of the factors contributing to the lower rates of shadow activities in the US, where it accounts for only 7% of total GDP, compared with the global average of 28%, according to the IMF’s 2015 report.

Use of Cash. The prevalence of cash transactions also contributes to the expansion of the shadow economy. It is challenging for authorities to effectively monitor and trace cash-based financial activities. By contrast, digital transactions—including credit cards, online banking, and mobile payments—leave an electronic trail that allows authorities to monitor and track financial activities more effectively. The shift toward digital transactions since 2000 has played a pivotal role in diminishing the magnitude of the shadow economy. (See “Access to Bank Transactions in Australia.”)

Access to Bank Transactions in Australia

These factors reinforce one another in ways that can set off a chain reaction: a vicious cycle of dependence, impoverishment, and mistrust. When the economy is weak and distrust of the public sector is high, governments struggle to gather taxes. The funds available for public services diminish. As funds for public services erode, governments often respond by increasing tax rates and regulations to bolster their revenues. This, in turn, pushes more individuals into informal employment as their confidence in formal institutions diminishes further, leading to still more skepticism and corruption, along with lower tax morale. This cycle, once underway, is hard to reverse. It takes a long time for governments to regain people’s trust so that they pay taxes and use its services effectively.

By using our framework on the fundamental drivers of shadow economy, government entities could evaluate which drivers are the most significant enablers of such activity in their country. For example, in developing countries, addressing economic hurdles and directly confronting corruption can yield notable results. The shadow economy often thrives in environments where formal economic opportunities are limited. Improving economic conditions and promoting transparency, integrity, and entrepreneurship can create an environment less conducive to informal economic markets.

Measuring the Shadow Economy

Unlike conventional transactions that are documented and accounted for, the shadow economy comprises a range of informal, unreported, and often illegal activities that evade traditional methods of measurement. Therefore, to gauge its impact, researchers and economists must look past official records and established business channels to other data sources. There are three main strategies for doing this, each with its own merits, drawbacks, and constraints.

Direct Approach. This approach uses representative household micro-surveys to investigate public opinion of the shadow economy, along with actual participation. The findings are then extrapolated to a larger scale.

- Pros. Surveys provide detailed insights into the shadow economy’s structure. They are particularly useful when other data is not available.

- Cons. Surveys draw information from only a fraction of the population. They are susceptible to design flaws and response bias—for instance, people tend to avoid reporting their own shadow activities. The surveys may thus underestimate the informal economy’s size. Language and social disparities may make it difficult to compare results across surveys.

Indirect Approach. The indirect approach deploys macroeconomic indicators and models, using various economic indicators such as discrepancies between national expenditure and income statistics, disparities between electricity consumption and reported economic activity, and the demand for currency in cash to estimate the size of informal economic activities.

- Pros. This approach typically leverages readily available data, making it relatively cost-effective.

- Cons. Each analysis measures a single aspect of the shadow economy instead of encompassing its complexity.

Multiple Indicators. This approach uses a model called statistical multiple indicators and multiple causes (MIMIC). By analyzing the rise and fall of key variables over time, MIMIC can explore the evolving relationship between the shadow economy and its enablers. Variables include tax burdens, self-employment levels, and unemployment data. This model yields relative estimates of shadow economy activity, often applied to groups of countries.

- Pros. MIMIC offers a more sophisticated analysis than other methods by considering multiple causes and indicators concurrently.

- Cons. The model generates relative estimated coefficients that require additional calibration. It cannot be exclusively applied to individual countries.

Given the complexity of measurement, only a limited number of studies have been published that compare the size of shadow economy across multiple countries using consistent methodologies. One ongoing database, released by the World Bank in 2018, covers shadow economy sizes and trends for 158 countries from 1991 through 2015. Remarkably, it shows a distinctive decline in the global average share of shadow activities by 6.7 percentage points—from 34.5% of total nominal GDP to 27.8%—over a span of 24 years. This decline can be attributed to factors such as economic growth and development, improved government regulation and enforcement, increased technology adoption and digitalization, and enhanced access to formal financial services. Nonetheless, there is still a long way to go for some countries that need to improve their government effectiveness in constraining shadow economy. Moreover, new technologies such as blockchain-based digital currencies and generative AI may also have profound impact on the shadow economy.

Methods for Mitigation

Assessing and mitigating the shadow economy in any country is a challenging endeavor. Nonetheless, it’s critical for governments to undertake the effort, starting with measuring the size and impact. As the saying goes, you can’t manage what you can’t measure.

We recommend a three-step process:

- Define Activities. Clearly identify the scope of activities encompassed within the shadow economy (e.g., informal activities, illicit activities, or household-based activity).

- Choose a Preferred Calculation Approach. Select a direct, indirect, or MIMIC approach as your primary analytic tool, based on the desired level of detail, available data, and available expertise.

- Cross-Check the Results. Employ an alternative calculation approach to cross-validate your findings. Present a range of shadow economy estimates rather than a single precise value. Different approaches will yield varying results. Use these findings, in consultation with international organizations, other governments, and experts, to design a course of action.

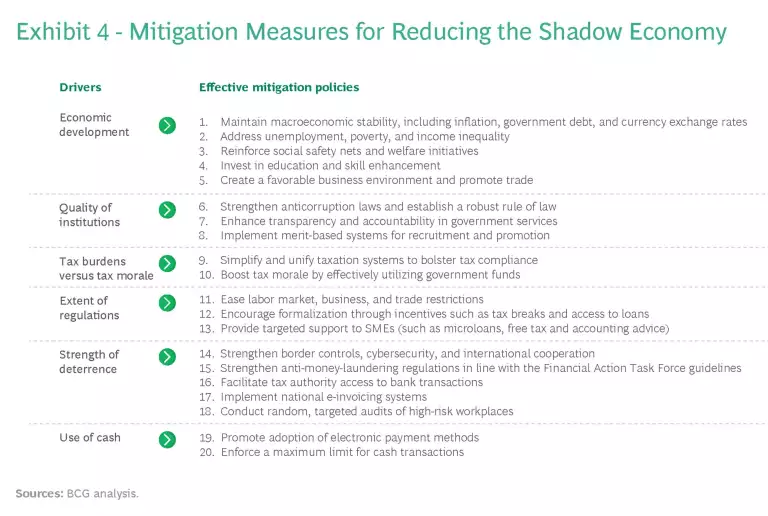

Governments worldwide have adopted diverse strategies to combat their shadow economies—from easing labor market restrictions to enhancing surveillance and imposing stricter penalties. There is no universal solution. Each approach should be tailored to the specific country context. Exhibit 4 provides a non-exhaustive list of effective policies that have successfully reduced the shadow economy, correlated with the six main drivers. It provides a starting point for identifying suitable measures for addressing particular drivers.

Conclusion

Government leaders in many countries are taking the problems of the shadow economy more seriously than they have before because of shadow economy’s profoundly negative effects on tax revenues, productivity, labor rights, institutional trust, and national security. We cannot eradicate the shadow economy completely—nor would we want to, because so many aspects of the formal economy are connected to it. Nonetheless, however expedient it may be to support it in the short term, constraints and limits are critically important for a country’s medium- and long-term economic growth.

By fostering economic stability, bolstering transparent and accountable institutions, and alleviating stringent regulatory restrictions, governments can unveil on the shadow economy. It can be tamed to become a more constructive aspect of society. The specifics will vary based on the circumstances for each country, but all these efforts have one thing in common: they are needed to pave the way for an economic landscape characterized by transparency and sustainable advancement.