The North American midstream sector is at an inflection point, one akin to the advent of shale in the 2000s. Over the past decade, surging oil and gas production drove broad-based growth in energy infrastructure across basins and commodities. In response, midstreamers deployed their tried-and-true playbook: build infrastructure ahead of production, secure long-term contracts, and capitalize on attractive commercial dynamics.

The next ten years, however, are going to look very different. Capital is flowing from liquids to gas, down the value chain, and into fewer basins. For some companies, this change will bring opportunities; for others, it will call for a very different playbook. By taking action in four areas, North American midstreamers can bolster their resilience and position themselves to drive shareholder returns in a rapidly changing macro environment.

A Winning Formula Under Threat

Like other infrastructure players, midstreamers grow by deploying capital underwritten by long-term offtake agreements that secure steady base returns, then incrementally add value to that fixed asset base. In other words, they are valued in large part based on their ability to deploy capital at attractive rates and grow free cash flow over time. In this way, they can be thought of as the “first derivative” of energy production: their performance is influenced more by the growth in oil and gas production (which necessitates new infrastructure) than by the absolute value of production itself. Accordingly, widespread shale growth over the past few years has allowed midstreamers to enjoy strong EBITDA-per-share growth and outperform broader market indices.

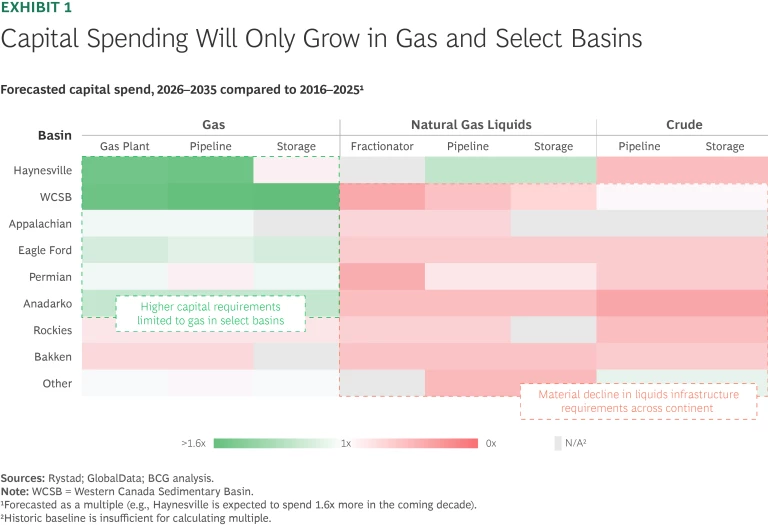

But an emerging shift has put this formula in jeopardy. Over the next decade, two-thirds of midstream capital is projected to flow into gas infrastructure, versus 50% over the previous ten years. Meanwhile, 80% will be allocated farther down the value chain in inter-basin infrastructure, as opposed to 65% in the past decade. Only one out of eight major basins will see increased capital requirements, versus five out of eight in the past ten years. (See Exhibit 1.)

Over the next decade, two-thirds of midstream capital is projected to flow into gas infrastructure, versus 50% over the previous ten years.

This development is partly a function of the growing role of gas in shale production (a natural geological phenomenon as basins mature). But it’s also a demand story. BCG analysis suggests that total gas demand across the US and Canada will increase by around 40% over the next decade, thanks chiefly to rising LNG exports and domestic power generation needs. Alongside oil’s projected anemic production growth from 2026–2030 and then slow decline from 2031–2035, this trend will result in a “gas-first” midstream environment. For midstreamers, the business implication is clear: little investment is required to maintain liquids volumes, while considerable investment is required to grow gas volumes.

This shift will create clear winners and losers.

Disparate Impacts in a Bifurcated Sector

Based on their business models and characteristics, we have defined two broad segments in the midstream sector: “basin players” and “market connectors.” The impending shift to downstream and gas makes this segmentation more relevant, as it underscores the disparate impacts we expect across the sector. The classification isn’t rigid, and some midstreamers straddle both segments. But as a framework, it’s analytically useful because it not only highlights companies’ different business characteristics but also reflects how their risk–reward profiles are evolving and what their future playbooks might look like.

- Basin players operate “production push” networks that capture molecules early in the value chain and carry them across multiple revenue-generating steps, from gathering and processing to intra-basin transport to fractionation. On average, 20% to 40% of their EBITDA is derived from marketing—roughly twice as much as market connectors. Their more volatile cash flow compels them to take on less debt; accordingly, they often trade at lower valuation multiples.

- Market connectors operate on a “demand pull” model, managing high-throughput corridor infrastructure that connects basins to end-use markets. Their assets are often large-scale and capital-intensive, underwritten by long-term contracts or regulated rate structures. Market connectors often have higher gas exposure. Typically, less than 10% of their EBITDA comes from marketing. Because of their more stable cash flows, investors tend to tolerate higher debt ratios. They also typically trade at a premium relative to basin players.

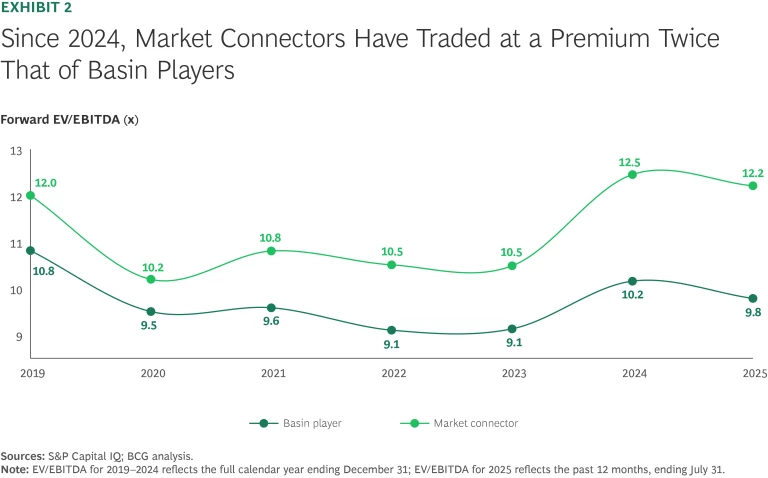

Recognizing market connectors’ earnings stability, the market has historically priced them at a modest premium (1.0 times EV/EBITDA above basin players). Over the past two years, however, that premium has effectively doubled. (See Exhibit 2.)

This valuation gap points to a structural divergence in growth potential between the two segments. The flow of capital toward gas and downstream and into fewer growth corridors is precisely where the market connectors sit. Basin players, on the other hand (especially those based in maturing liquids basins such as the Bakken and the Rockies), are increasingly outside the action. Understanding this divergence is critical for envisioning the prospects for North American midstream companies over the next decade.

It’s important to note that just because market connectors appear better positioned doesn’t mean their future is assured. They face consequential strategic decisions: How to invest in 20-year assets when policies change so much from administration to administration? How will geopolitical shifts affect global energy flows, and which types of infrastructure will be most resilient in different scenarios? How will diverging basin outlooks (e.g., Haynesville strong; Niobrara weak) and different demand drivers (e.g., LNG versus data centers) affect inter-basin infrastructure?

For basin players, given the softening demand for existing infrastructure and their flagging organic growth opportunities, the decisions are starker: How can they improve their fate? The traditional playbook is no longer sufficient.

How Basin Players Can Improve Their Prospects

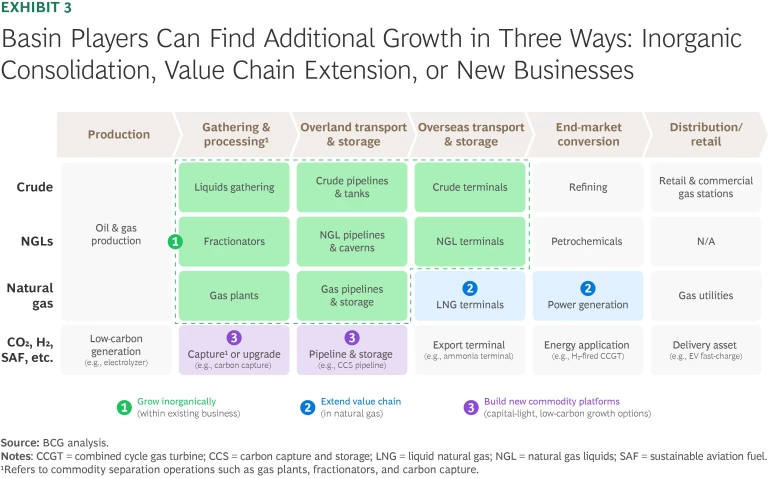

Basin players will need to be bolder in their pursuit of growth, looking beyond their core organic growth model. We see three viable options. (See Exhibit 3.)

Consolidate in-basin—or, do more of what you’re doing. Given today’s valuation environment—where gas-weighted and downstream platforms are trading at a significant premium—acquiring gas-growth platforms is likely to be dilutive for basin players. In-basin consolidation, however, remains a proven strategy. Such deals offer a variety of clear synergies, including cost takeout (overhead as well as operational), removing network bottlenecks, and marketing optionality. In-basin acquisitions also boast a strong track record; historically, they have outperformed peer total shareholder return by about 10% in the six months following the deal. We have also seen the inverse: investors penalizing out-of-basin acquisitions, which have underperformed by roughly 11% over the same period.

Extend down the value chain opportunistically. In the past, midstreamers looking for opportunity downstream often considered petrochemical investments. But the combination of mixed returns and a global petrochemical supply glut mean that this strategy is not viable. Today, the most compelling opportunities lie in the gas value chain for LNG and power generation. Operators can extend downstream by pursuing one of two approaches:

Today, the most compelling opportunities lie in the gas value chain for LNG and power generation.

- Supply Commitment. Here, the company commits to delivering molecules rather than selling capacity (the traditional commercial model). While this approach entails additional risk/reward considerations (namely, the commitment to deliver molecules, with penalties for breaches), some midstreamers are well positioned to manage them. Optionality—including access to storage, swing capacity, and multiple supply routes—is built into their infrastructure. Midstreamers can thus uniquely capture the reward upside while limiting the risk downside.

- Direct Ownership. Alternatively, the company can use its capital to support the development of liquefaction or power-generation facilities through equity stakes. Again, this model brings additional risk, as the company must develop and operate new assets beyond its core capabilities.

Value chain extension, with its associated risks, is justifiable under one of two conditions: if it captures incremental upside or if it enables the company to draw on upstream infrastructure to utilize (and thus monetize) otherwise unused capacity. In the former case, some data center users have shown a willingness to pay a substantial premium for power (10%–20% in $/megawatt hours) in the near term. Midstreamers can capture this premium by serving as a one-stop-shop for data centers—pairing gas supply with power generation—thus simplifying and accelerating project timelines. In the latter, we’ve seen project ROICs improve by up to 4% through such extensions, which fill spare capacity upstream from a new demand source, thanks to incremental EBITDA generated across an existing asset base.

Enter new (low-carbon) value chains—with caution. As decarbonization policy vacillates, low-carbon plays are unlikely to spark material EBITDA in the near term. But companies should keep their options open, as policy shifts can easily happen over the mid- to longer term (for example, following the 2026 US midterms or the 2028 general election).

Midstreamers should pursue immediate, capital-light measures that can improve competitiveness; examples include compressor tuning, leak detection, flare gas recovery, and other operational upgrades. In addition to lowering emissions, these often high-ROI, low-risk moves can also reduce operating expenses—a benefit of particular importance where shippers have multiple infrastructure alternatives. Such a scenario will become increasingly relevant in slowing liquids-rich basins.

In parallel, midstreamers can begin building capital-light optionality in emerging carbon markets. Carbon capture and storage is the most likely near-term candidate. Many such projects may not be NPV-positive today, but the possibility of future policy shifts makes it prudent to prepare now. Tactical moves could include forging joint ventures with buy-up rights. While such optionality isn’t free, the goal is to build a differentiated position if the economic or policy environment changes, while minimizing near-term ROIC dilution.

Stay ahead with BCG insights on energy

With New Context, New Capabilities

As gas becomes increasingly dominant and operators begin to reposition themselves, there is a set of no-regret capabilities that market connectors and basin players alike should begin building now. For the basin players that need to change their fate, these actions are musts.

Conventional wisdom points to two areas:

Commercial and Marketing. We expect North American gas markets to experience greater volatility over the next ten years. Continental gas supply has increased by around 30% in the past decade, while storage and transmission infrastructure has not expanded measurably. In addition, as LNG production capacity expands (potentially accounting for up to 25% of demand by 2035), periods of underutilization may occur, resulting in dynamic moves between the power and LNG markets. We estimate that daily swings of up to 5 billion cubic feet per day will not be uncommon as gas flows to the highest returning market, whether domestic power or LNG feedgas.

We believe that this environment (along with seasonal fluctuations in natural gas demand) will feature frequent dislocations in price and flow. Accordingly, commercial and marketing capabilities are becoming increasingly important as a means of managing—and capitalizing on—this demand volatility. Critically, midstreamers can navigate such conditions without introducing earnings volatility (and risking associated valuation compression) by monetizing dislocations through ratable term sales, rather than through more intensive speculative trading activity. This opportunity comes with the added benefit of being a near-term, capital-light way to drive EBITDA growth.

- Advanced Analytics and Simulations. The volatility we anticipate will also cause netback variability, so the ability to model, simulate, and anticipate flow and pricing will be critical. Simulation tools can also help operators steer molecules toward destinations offering the highest netback, unlike the limited (or siloed) visibility into netback opportunities many have today.

Less obvious are actions in these two areas:

- Customer Experience. In the past, midstreamers in basins with strong volume growth benefited from attractive commercial dynamics. But in a world where this growth is slowing (or volumes are in outright decline) and where pipe competes with pipe, buyers can be choosier. The quality of service to shippers becomes more important. Rather than flat tariffs, customers will increasingly expect commercial flexibility, responsiveness, and clear value in exchange for their volumes. While commercial flexibility often leads to lower per-molecule margins, this trade-off might be worthwhile if it helps midstreamers capture interruptible flow and keep assets full.

Joint Venture Structuring and Partner Management. Midstreamers have long pursued partnerships and joint ventures, often retaining operating control while using institutional capital to manage exposure to large projects. Increasingly, they will need to forge partnerships to build operational capabilities, whether downstream into power or LNG or laterally into low-carbon infrastructure.

These agreements will inevitably be more complex. Partnerships in value chain extensions, for example, will require midstreamers to work with counterparties with different risk profiles and commercial norms—such as commodity exposure, merchant dynamics, or shorter planning cycles. In low-carbon ventures, midstreamers may want to contribute land or rights-of-way and preserve the right to buy out partners at trailing EBITDA while minimizing upfront capital. Such terms present unique structuring challenges; midstreamers will need a clear internal playbook for joint venture structuring that identifies the operational and commercial adaptations they are willing to tolerate in exchange for partner know-how and opportunity option value.

It’s clear: the next decade will not offer the same across-the-board growth for the midstream sector. Companies should expect considerable volume variability across commodities, the value chain, and basins. An evolving landscape with considerable market and policy uncertainty will create distinct winners and losers. Whether market connectors or basin players, midstream companies should take action now to build resilience, differentiate from peers, and position themselves for a profitable future.