For the CEO

A message from our editor on this critical topic.

Just when you thought the job of leading a multinational corporation couldn’t get any harder, tariffs have roiled the global economy.

Whatever new normal may settle over the business landscape in the months and years ahead, CEOs are in the meantime likely to face a protracted period of uncertainty—and sudden upheavals—that will perpetually alter the calculus for dealmaking. But leaders must forge ahead if they are going to access new markets, acquire new capabilities, and build resilience against future shocks.

While M&A will continue to make sense in some instances, joint ventures and alliances offer CEOs a more flexible option for driving growth and hedging against risk, especially during periods of heightened uncertainty.

“The reality is, joint ventures will come back much faster than M&A,” says Edward Gore-Randall, a BCG managing director and partner and global leader of the firm’s work in joint ventures. “While most investors expected some tariffs, almost 90% were surprised by the scale and scope—and the current uncertainty means joint ventures, which are much more nimble than traditional M&A, will come back faster.”

But realizing significant value from joint ventures can be tricky. No two are the same, failure rates are high, and they are often more complex to structure and manage than an outright merger or acquisition.

Still, there are steps CEOs can take during the structuring and management phase to avoid the common mistakes that can undermine a joint venture. The right actions can even help businesses thrive through uncertainty by forging a value-creating partnership that brings the capabilities of two strong companies together—while leaving space to pivot as business conditions change.

The Enduring Allure of Alliances

Joint ventures can take many forms, from contractual arrangements or licensing agreements to complex nonequity partnerships and consortia all the way to incorporated joint ventures.

Whatever the shape and size, such alliances have proven remarkably resilient over the last two decades—particularly during periods of economic stress. In 2020, for example, the pandemic-induced global recession spurred a 6% increase in joint venture activity while M&A saw an 8% to 10% percent drop.

Current economic conditions suggest this trend will continue. While joint venture and M&A activity both have slowed in recent months, joint venture formation is expected to rebound faster—thanks to the greater degree of nimbleness and risk mitigation that can be baked into the deals.

“The very fact that there’s so many joint ventures and alliances tells us that it’s an attractive proposition, compared to putting all your eggs into a 100-percent-owned subsidiary,” says Farok Contractor, distinguished professor in the Management and Global Business department at Rutgers Business School. “If you have x billion or x million dollars to invest, would you rather invest in two fully owned operations, or would you rather invest in six alliances, spreading the same amount of money but significantly spreading the risk?”

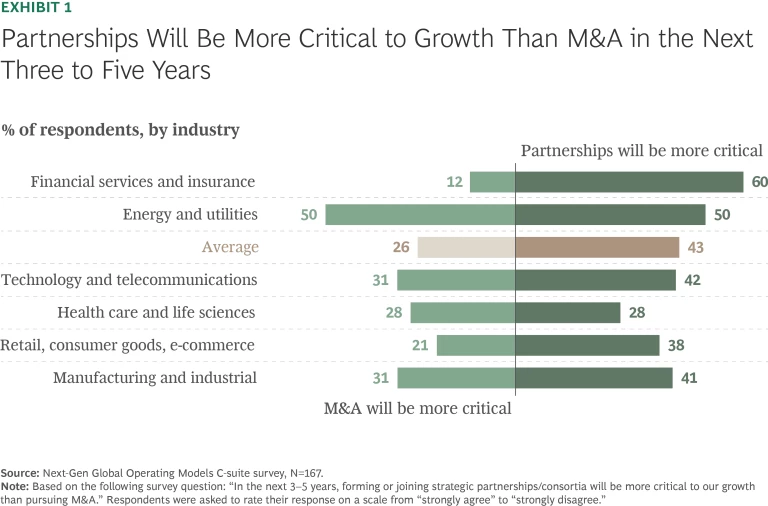

Indeed, 60% of business leaders recently surveyed by BCG said forming joint ventures and partnerships will be more critical to growth over the next three to five years than pursuing M&A. (See Exhibit 1.)

“In this environment in particular, with greater uncertainty, I think there are certainly situations where joint ventures will be beneficial or superior to a full acquisition,” says Daniel Friedman, a BCG managing director and senior partner and global leader of its transactions and integrations business.

When CEOs Get Joint Ventures Wrong

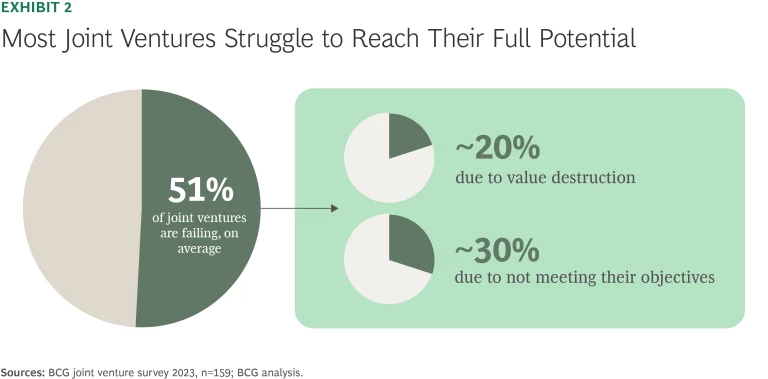

For all their many virtues, joint ventures are hard to get right. BCG’s analysis of public research and its own surveys shows that 51% of joint ventures fail to reach their full potential. (See Exhibit 2.)

The seeds of poor outcomes are usually sown during the predeal phase, says Friedman. “You must have a very clear articulation of why we are doing this and how this creates value,” he says. “If that’s not in place, nothing else works.”

The deal also needs to be a good one for all parties involved.

“One of the most common errors CEOs make is to negotiate a JV or partnership like they would an M&A transaction,” says Gore-Randall. “A partnership needs to be designed and built collaboratively to deliver value for both parties.”

One of the most common errors CEOs make is to negotiate a JV or partnership like they would an M&A transaction.

—Edward Gore-Randall, Managing Director and Partner

For this reason, says Marc van Grondelle, a BCG partner and director, it is critical to have specialist advisors who can think beyond a traditional M&A transaction and work to achieve the objectives of both parties.

“JVs and partnerships often struggle when designed by generalists, however talented,” he says. “To do it well, it is essential to know all the practical pitfalls and causes for underperformance—to have witnessed others struggle and captured the lessons from it.”

And with uncertainty in the global economy fast becoming the rule rather than the exception, it is imperative that CEOs establish an operating procedure and an exit strategy built for fast-changing times.

“Scenario planning together, agreeing on ‘How do we work together, how do we unlock value? And under which scenarios does it no longer make sense for you and for me to continue?’ These are an absolute must-have from my perspective,” says van Grondelle.

Both companies also need to recognize that contributions and success come in many forms.

“We often see discontent sown when parties fail to recognize contributions beyond tangible assets or profit today,” says Gore-Randall. “Likewise, judging success by just the profits within the JV—and ignoring the value delivered directly in the shareholder’s P&L or in the IP, know-how, or optionality it creates—will greatly understate the JV’s true contributions.”

Another factor that can spell the difference between success and failure is governance. How decisions will be made, how often shareholders will meet, what decision-making rights each party will have, and how conflicts will be resolved all need to be agreed upon in advance, says Friedman.

Joint ventures only thrive when they are supported by shareholders.

Failing to maintain an investor mindset when managing the joint venture is another common error. All parties must recognize that joint ventures only thrive when they are supported by shareholders—for example, by providing access to resources and capabilities, says Gore-Randall. At the same time, he adds, they must not suffocate the joint venture with red tape or micromanagement.

Finally, differences in culture—both corporate and social—can have a significant bearing on outcomes.

Rosabeth Moss Kanter, a professor at Harvard Business School, recalls how a set of Japanese and US firms approached a potential US-based alliance in very different ways.

“The Japanese companies were really interesting because they were very patient, and in many cases they were using the fact of an alliance to begin to build a relationship,” says Kanter. “But the US companies on the other side were very eager to make a deal. They were not comfortable with the ambiguity of an alliance. They wanted to be in total control, and that was a cultural difference.”

The CEO’s Joint Venture Checklist

In addition to avoiding common mistakes, CEOs also need to proactively lay the foundations for a successful joint venture. The following five actions can help guide their efforts.

1. Cocreate rather than negotiate. Joint ventures are not singular undertakings. They involve two or more parties that come to the table with their own agendas. The key is to build a partnership together that delivers value for all involved.

Using experts who specialize in designing and structuring joint ventures can help set the right tone for the overall process and help ensure the partnership is mutually beneficial.

“It’s critical to recognize [that] a joint venture needs to be successful for both parties. And that really starts from the outset, where it’s key to work together to design a partnership that meets the strategic objectives of everyone,” says Gore-Randall.

This includes having candid conversations from the very beginning to fully assess the extent to which each partners’ goals can align and complement each other.

It’s also important to determine how much optionality each party wants the joint venture to have to respond to changing business conditions. Establishing a stringent path forward can be as much a valid avenue as setting guardrails and leaving space to flex. But whatever the approach, it should be proactively determined in advance.

2. Invest sufficient time upfront to align with your partner(s) on all aspects of the joint venture. It cannot be overstated how important it is for all parties to invest enough time in the early stages to get genuine alignment on the joint venture’s strategy, business plan, governance, and operating model.

“Determining the governance and operating design up front—so there’re no surprises later on, when it becomes much more complicated to address—is very important,” says Friedman.

When all parties decide in advance how they will work together to best leverage the capabilities of the parent companies, a joint venture becomes greater than the sum of its parts, says Gore-Randall.

“The worst thing for the early days of a joint venture is to lack clarity and alignment over the strategy and to not resolve disagreements about the business plan,” says Gore-Randall. “These things need to be nailed down before a joint venture is launched to give it the best chance of success.”

Joint ventures that start out on the right footing can stumble due to a lack of discipline and communication between the parent companies.

Deciding who should run the joint venture largely depends on its purpose and how closely the parent companies manage it. Once the leaders of a joint venture are plucked from their parent companies, giving them measurable milestones to meet—and a career path back to the parent—is important for maintaining performance and morale.

“They need to know how their performance is assessed, who will be managing them while they are with the JV, and how their journey back to the parent company will be managed,” says van Grondelle. “Otherwise, people become very uncertain and start looking over their shoulder.”

Finally, even joint ventures that start out on the right footing can stumble due to a lack of discipline and communication between the parent companies, says Friedman. So hold monthly or quarterly meetings to ensure key targets are met. And during periods of heightened unpredictability, keep the lines of communication open.

3. Leverage the flexibility of the joint venture to find win-wins for the shareholders. A joint venture’s long-term success ultimately depends on whether all shareholders are benefiting from it. The parent companies can contribute to the partnership in a broad variety of ways, from intellectual property (IP) and know-how to physical assets, capital, customer relationships, and market access.

How these contributions support long-term objectives can help all parties remain open-minded when valuing assets.

“There are times when you have to value assets that are actually incredibly difficult to value today,” says Gore-Randall. “And that’s where you can explore a plethora of variable valuation techniques, such as royalties, preference shares, and milestone payments.”

It’s important to agree on what comprises IP during the design phase. For example, a production process may not have much in the way of patentable technology or knowledge, but could require “good operators explaining how to run the plant,” says van Grondelle. In fact, he says, 90% to 95% of intellectual capital is nonpatentable know-how.

You can absolutely structure JVs and partnerships where revenue, dividends, and controls are not in proportion to the equity.

—Marc van Grondelle, a BCG partner and director

How profits from the joint venture are shared needs to be crystal clear from the beginning. In many cases, the split is guided by how much each partner is contributing to the venture and how risks are distributed. It is important to bear in mind, though, that each partner’s profit share does not have to align with its equity participation.

“You can absolutely structure JVs and partnerships where revenue, dividends, and controls are not in proportion to the equity,” says van Grondelle.

He cites the example of a joint venture in which one partner has 75% equity and the other has 55% of the profits and 100% of material control. “In a case such as this, it is vital to ensure protection of key brands and enable the exercise of control without the optic of dominance,” he says.

4. Have an exit strategy from day one—and stress-test it under different scenarios. Joint ventures, alliances, and consortia are frequently put together for a specific project, such as drilling a new oil field or operating a toll-road concession in a public-private partnership. While some have a defined lifetime, many don’t. So having open, frank discussions about how the joint venture might end can avoid serious headaches down the road.

“The successful exit really starts at the inception of the joint venture,” says Gore-Randall.

Agreeing up front how the exit can be triggered, what the shareholders’ rights are, how valuations are assigned, and what mechanisms would be employed can all make for a smoother exit—especially if the shareholders are no longer on good terms.

It should also be determined from the outset how any IP generated by the venture is used once the partnership ceases.

An open dialogue from the beginning about exit scenarios can also build trust.

For example, the IP generated by the partnership can be jointly owned by the parent companies. Or if one party brings IP into the joint venture and the other provides market access, then the former may look to own the rights to any new intellectual property developed by the partnership. A third option might be for one partner to take ownership of joint IP but allow the other to use it under a licensing agreement.

An open dialogue from the beginning about exit scenarios can also build trust. “The moment you start talking to your partner about ‘How do we deliver success?’ you can also say: ‘What does failure look like under different scenarios?’” says van Grondelle.

Finally, if a joint venture is terminated earlier than scheduled, CEOs should not see it entirely as a failure—because both parties likely learned valuable lessons from the alliance, says Rutgers’ Contractor.

“There are benefits that go beyond the capture of money in terms of insights into a technology area or insights into a market,” he says.

5. Take an investment mindset and remember the role culture plays in success. Building a successful joint venture takes investment and cooperation by all parties concerned—but the parties also need to give the venture sufficient space and separation to be successful in the marketplace.

“Finding the balance between micromanagement and disinterest is key to a successful governance model,” says Gore-Randall. “It’s important to support and invest behind a joint venture and take the perspective that you aren’t reducing your stake in your contributions but rather investing behind the combination.”

Approaching the alliance with a spirit of humility and a desire to learn about a particular market is also important for bridging cultural differences between parties. Kanter cites an example of an auto alliance in which one company was keen to learn more about the industry while the other wanted to push the first company around.

“When the whole thing fell apart, it was the first company that was good at learning that managed to carry forward that set of products in the auto industry,” says Kanter.

BCG’s van Grondelle also cautions against letting a joint venture’s culture grow organically as opposed to proactively shaping it.

“You choose which one of the [parent] cultures is dominant, or whether you create a separate, standalone culture,” he says. “You should not let the culture just happen. You should consciously create it,” he says.

Structuring and managing a joint venture can be harder than acquiring a company with complementary technology or market access.

But with global economic uncertainty at its worst since the COVID pandemic, collaborating with another company through a joint venture can help test unfamiliar waters before taking the plunge and committing capital for an undefined period. It also allows CEOs to invest the same capital across several bets—which can prove very attractive when the global macroeconomic outlook is unclear.