The energy transition has entered a new phase. Over the past 36 months, the global energy landscape has evolved significantly.

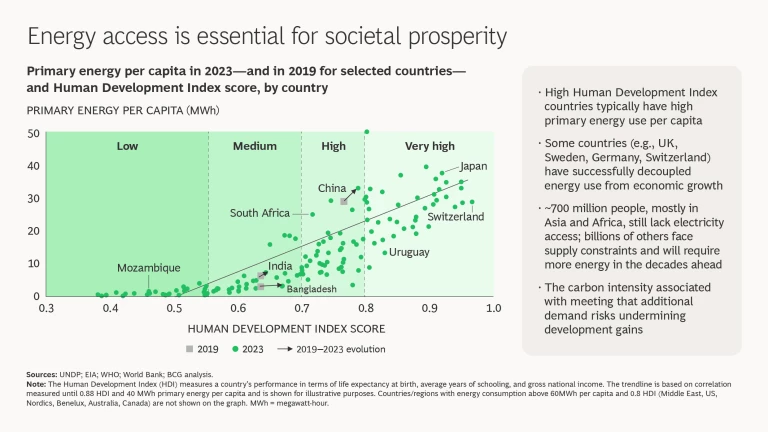

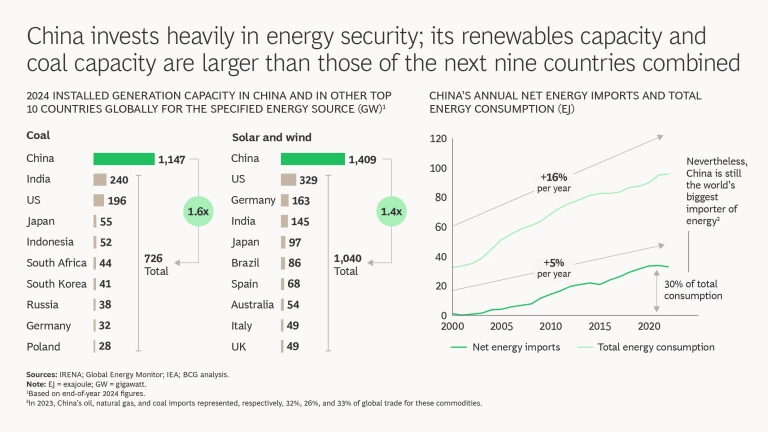

Among the most notable developments is the increasing emphasis on energy security and affordability. This reflects the fact that access to energy underpins economic vitality and human prosperity. Yet the increased carbon emissions associated with meeting the world’s energy needs risk undermining those very gains. Failing to price in the externalities of CO2 emissions doesn’t make them disappear.

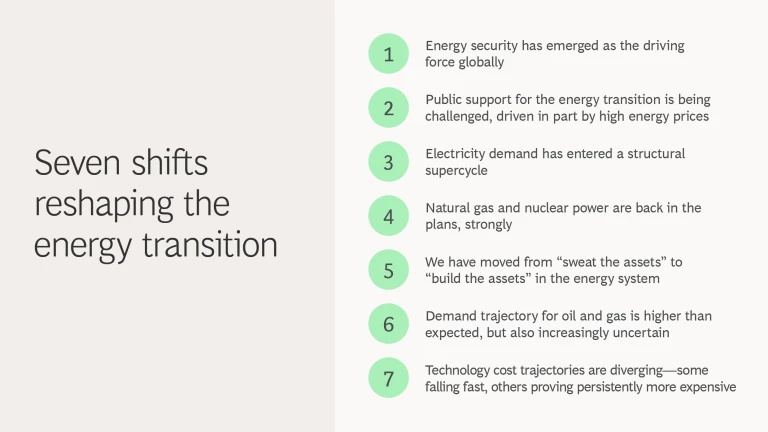

That said, the energy transition remains a fundamental secular shift. It is, however, unlikely to be a linear one—with the road ahead marked by uneven progress and occasional setbacks. It is also important to note that there is no single transition, but multiple country and regional transitions unfolding with differences in pace and technology choices. Still, the evolving and complex environment we observe today does not signal a retreat from the energy transition overall: in many cases, energy security and affordability can be aligned with decarbonization goals.

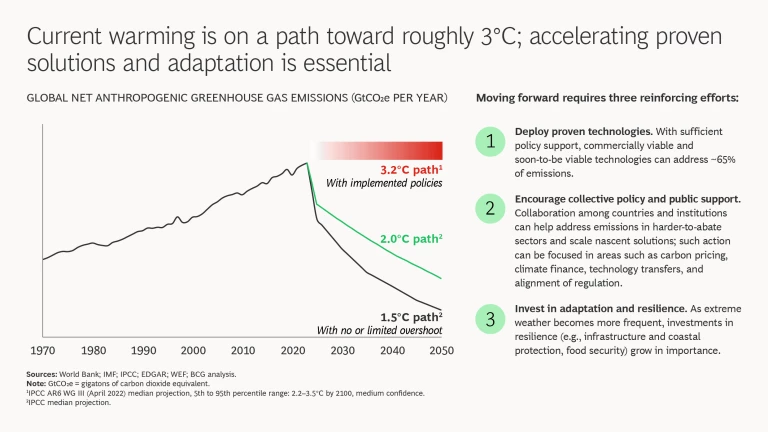

The question now is not whether these transitions will continue, but how and at what pace. Accelerating progress remains essential. The world is on track to reach a level of warming that significantly exceeds 2°C above preindustrial levels, and momentum on climate action is weakening in some countries. Multilateral alignment is proving harder, even as strong business cases for action persist. Moving forward at pace therefore requires three reinforcing efforts: accelerated deployment of commercially viable decarbonization technologies (which can address approximately 65% of energy-related emissions), encouragement of collective policy and public support, and preparation for a warmer world through smarter adaptation.

This publication, developed by BCG’s Center for Energy Impact as a follow-up to our 2023 report, is intended to help stakeholders make sense of the profound shifts underway in the global energy system and navigate its ongoing transition. In an environment filled with conflicting signals and information, our fact-based analysis seeks to bring greater clarity to the path forward.

Our report is structured in three parts. The first section takes stock of where we stand by exploring seven shifts that are reshaping the transition. Some of these changes create headwinds for the transition, while others produce tailwinds. Our assessment is based not on subjective judgments, but on observations of current trajectories. The second section explores four major implications of these shifts. The third section offers targeted recommendations for different stakeholder groups.

This report aims to cut through the noise with realism—providing a clear-eyed view of the path ahead based on fact and action.

The following summary, based on the full publication developed by BCG’s Center for Energy Impact, helps stakeholders make sense of four profound implications stemming from major shifts in the global energy system.

The Sustainable Advantage: Build lasting impact through sustainability

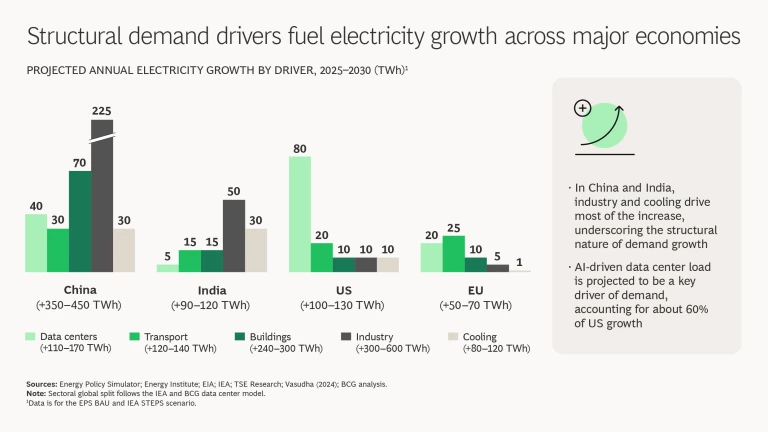

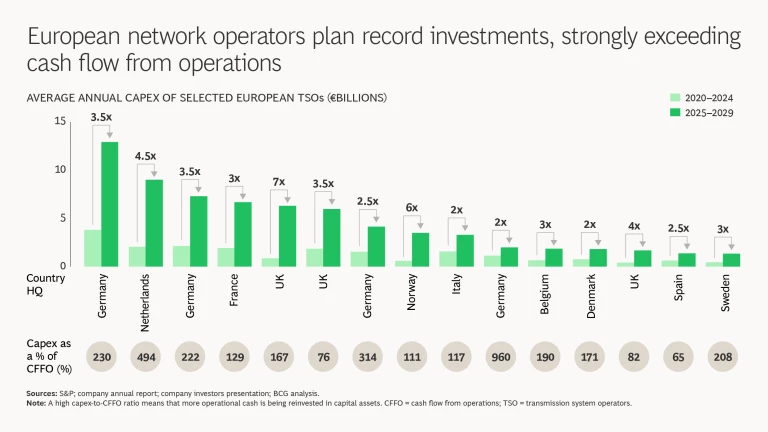

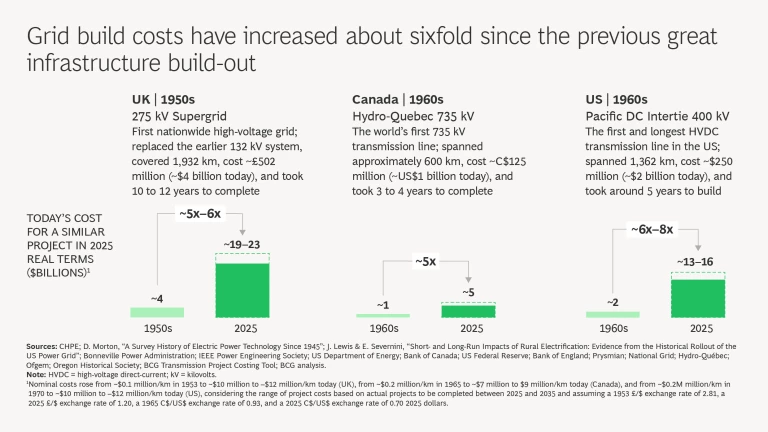

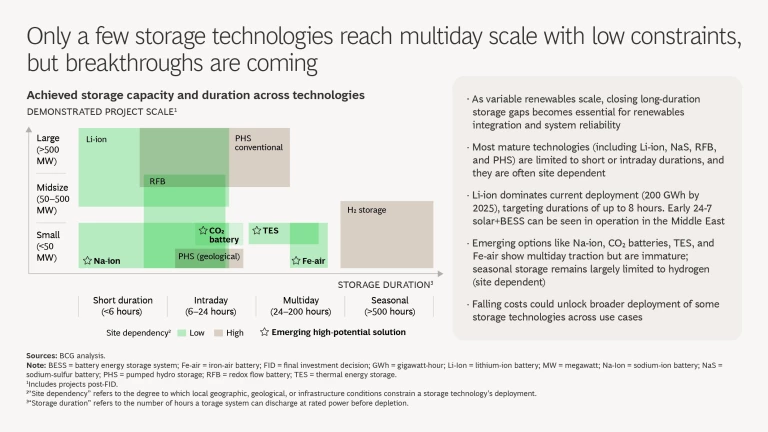

Implication 1: We need to reduce the overall cost and accelerate the build-out of enabling infrastructure

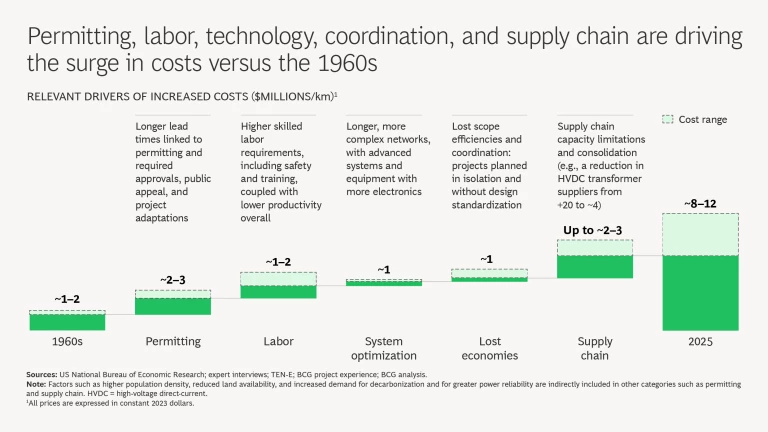

The cost of delivering large-scale grid infrastructure has increased about sixfold since the last major build-out, driven primarily by permitting delays, labor constraints, rising technical complexity, and supply chain bottlenecks. This is the case not only for electricity grids, but more broadly across all energy infrastructure. These pressure now risk slowing the energy transition and raising end-user costs. Reducing cost and accelerating delivery will require a combination of five levers:

- Stress-test current demand and supply scenarios to ensure that we build the infrastructure truly needed in a changing energy landscape.

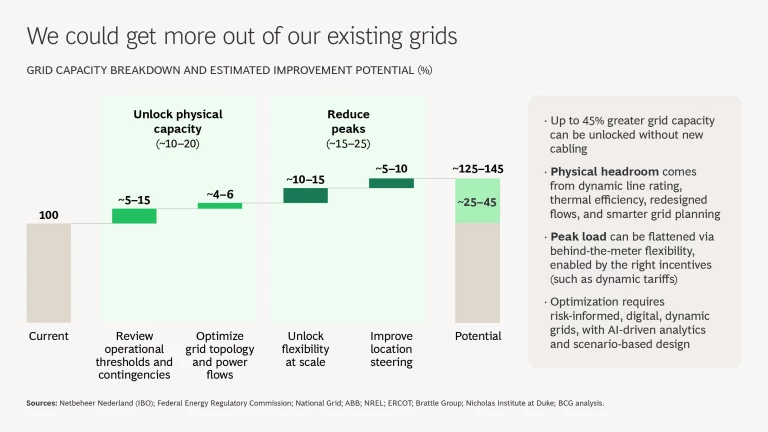

- Unlock more capacity from existing assets by applying advanced analytics, modernized risk frameworks, and dynamic operations, while making smart tradeoffs between performing targeted upgrades and deferring large-scale overhauls.

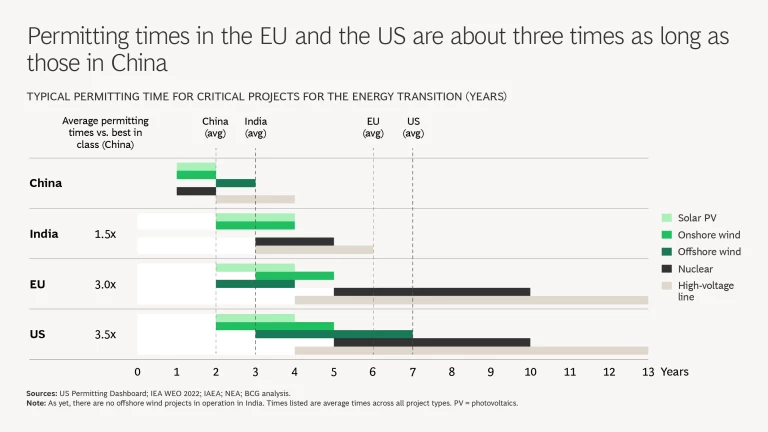

- Urgently accelerate permitting to help lower risk premiums while ensuring robust public engagement and environmental safeguards.

- Improve capital project execution through more standardized design, tighter project controls, and greater strategic engagement between customers and suppliers to scale reliable supply chains for items with long lead times.

- Reevaluate prior design choices (such as underground cable versus overhead line, and DC versus AC configurations) in light of recent cost escalations, to ensure that legacy decisions still make economic and operational sense.

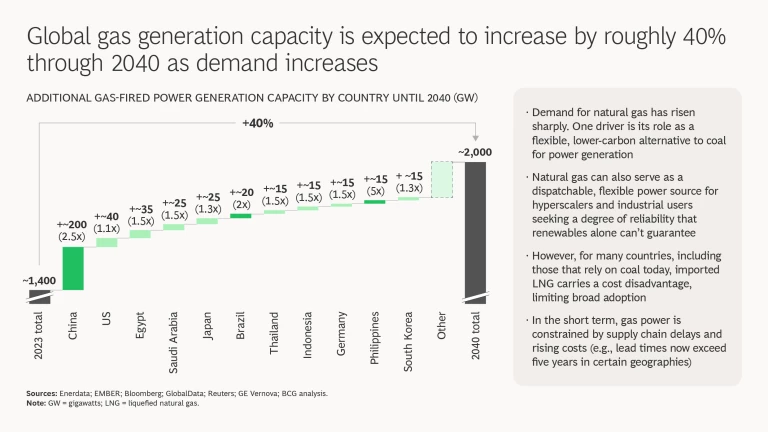

Implication 2: We can accelerate progress by doubling down on proven technologies and placing strategic bets

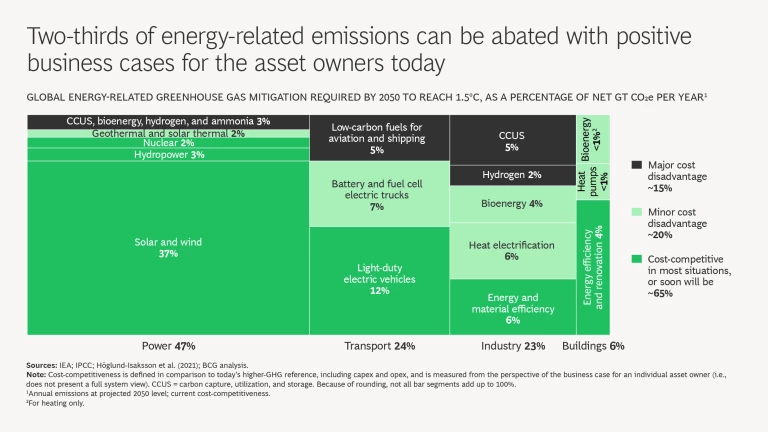

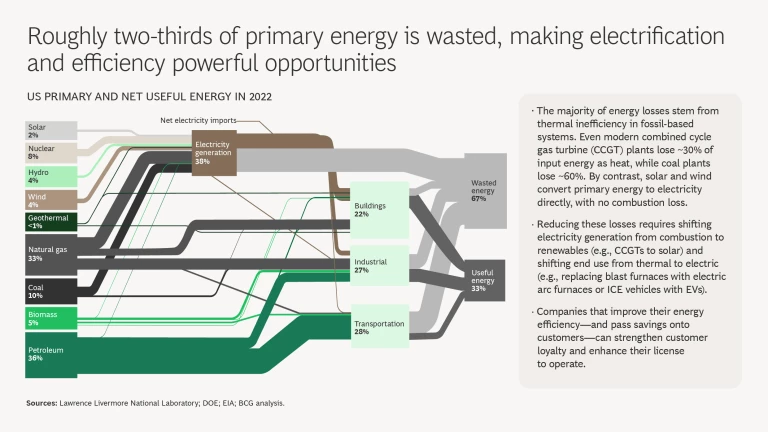

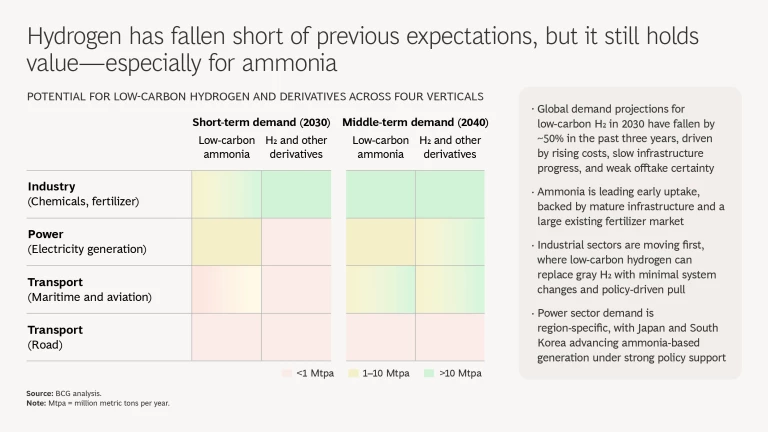

Roughly two-thirds of energy-related emissions can be addressed using commercially available technologies, especially in parts of power generation and in electrifying certain end uses. In many cases, deployment still depends on structural support—whether through contracts for difference, tax credits, or policy mandates. The transition’s success will hinge on what is already “in the money” and on which business cases that are not yet “in the money” can be strengthened through clear and stable policy frameworks. Technologies like wind, solar, and EVs have benefited from this kind of support for decades, and largely still do.

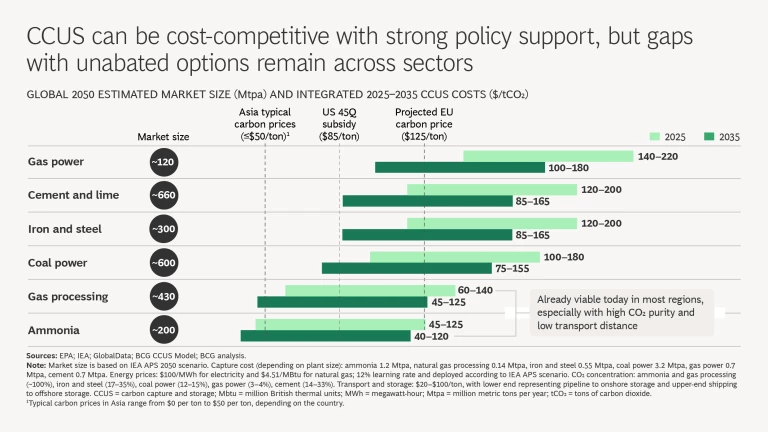

The impact can be material: gasoline demand falls by 19,000 barrels/day (or diesel demand by 24,000 barrels/day) for every one million EVs that take to the road. BCG modeling shows that as the EV market expands, CO₂ emissions from light-duty vehicles could drop by nearly one-third by 2035. There is a similar opportunity to facilitate the development of solutions for harder-to-abate parts of our emissions. Gas power with CCUS, for instance, is projected to be economically viable by 2035 under a carbon price of $125/ton, a gap that can be closed today through carbon contracts for difference.

First CCUS projects, from gas turbines to cement kilns, are being sanctioned across power and industry. These are not moonshots, but bankable with the right underwriting. Rather than separating technologies by cost alone, we must differentiate by system role, substitutability, and maturity, and design support accordingly. A strong deployment pipeline depends on treating cost-effective scaling and strategic bets as part of the same strategy.

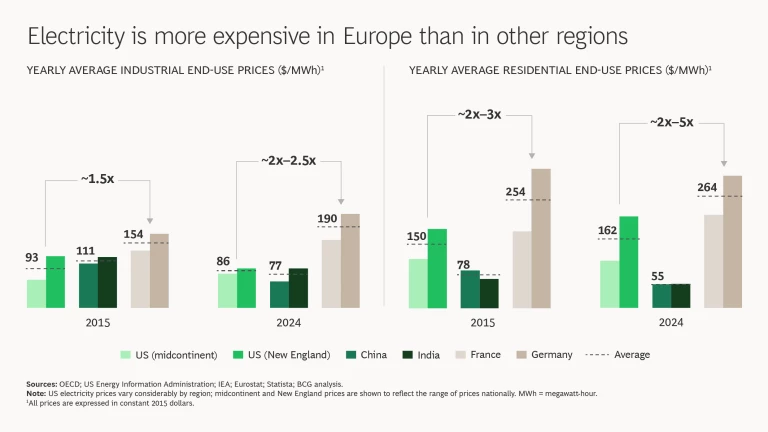

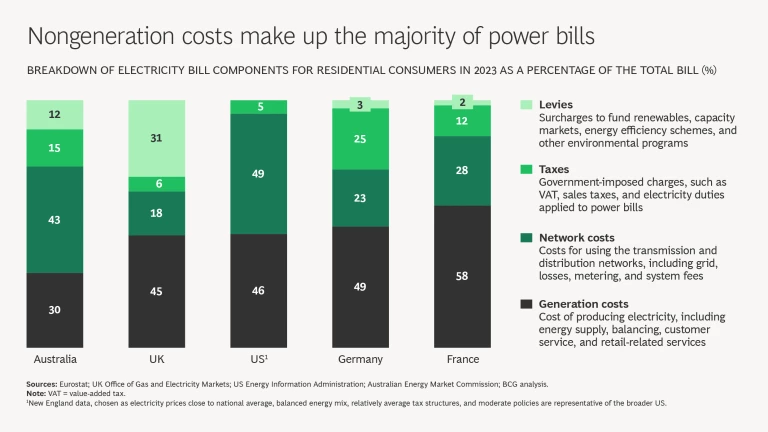

Implication 3: Energy affordability and customer agency are essential to sustain public support for the transition

The credibility of the energy transition depends not only on cost reductions, but also on who pays, and how. In many countries, nongeneration costs such as grid charges, levies, and taxes make up more than half of residential electricity bills. When these costs are passed through via flat-rate or regressive structures, they disproportionately burden lower-income households and small businesses. That erodes political support and fuels resistance.

But affordability isn’t just a constraint to manage, it’s also a lever for change. When consumers are empowered to shape their energy use—through flexible pricing, rooftop solar, community energy, or participation in demand-side markets—they become allies in the transition. This is even more likely in a process of change that carries other consumer benefits such as reduced air pollution. Demand-side activation is not an optional add-on, but core infrastructure for transition success.

A new generation of customer-facing energy models is emerging: communal storage platforms, public utilities that reduce pass-through costs, and digital tools that allow households to optimize consumption in real time. These are not just ways to lower bills; they are ways to build enduring support for the transition.

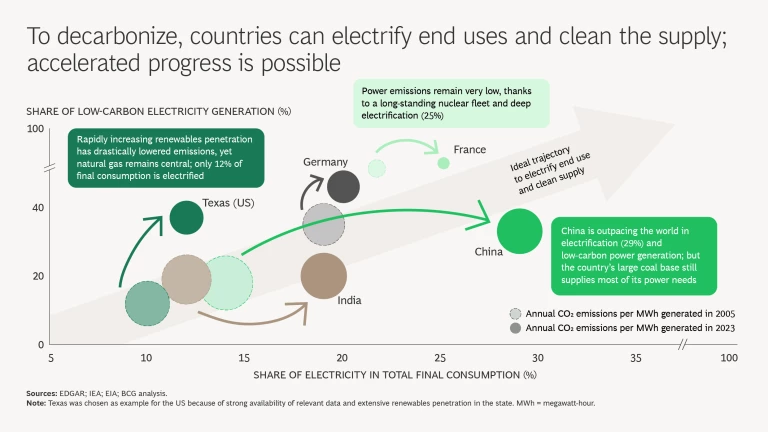

Implication 4: The transition will vary across countries and regions—and strategies must follow suit

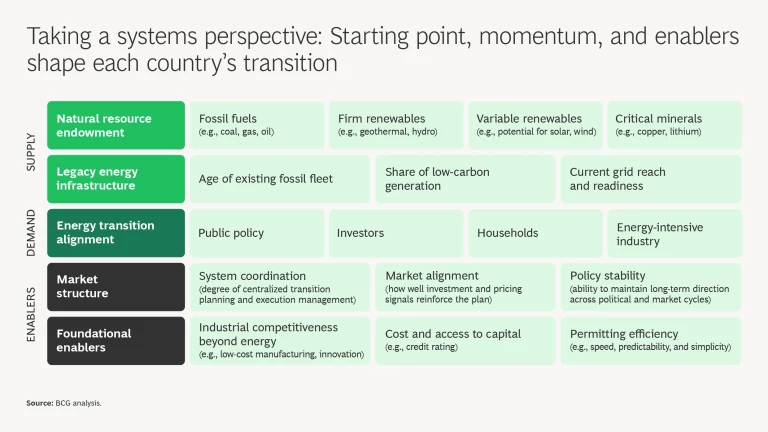

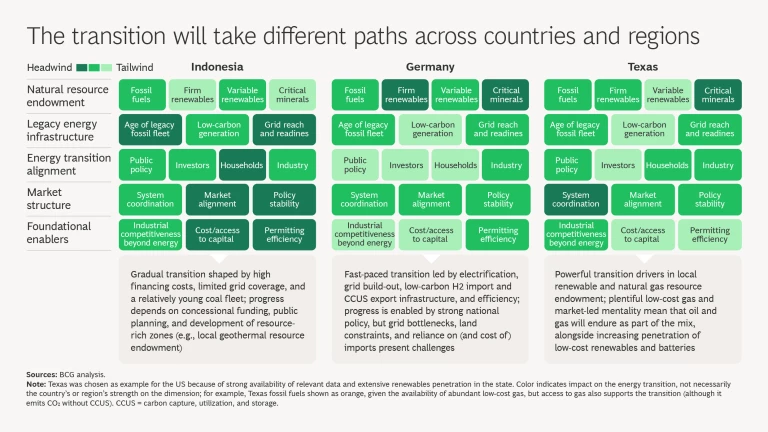

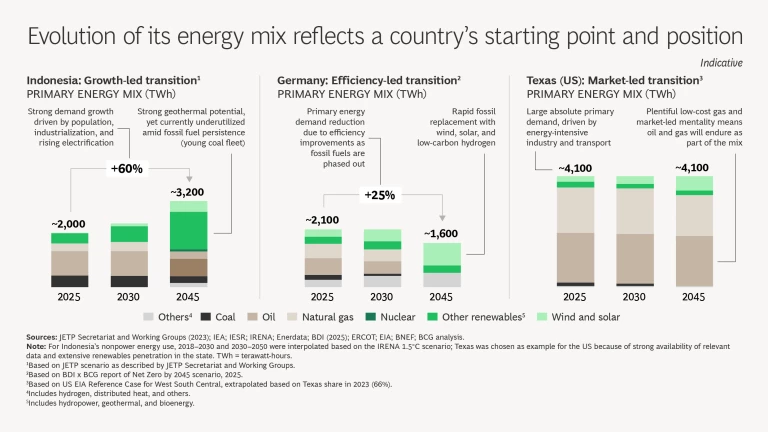

The core pillars of the energy transition are universal: maximize energy efficiency; scale renewables; deploy low-carbon firm power; build grids; decarbonize industry through electrification, CCUS, and low-carbon fuels; and capture or offset residual emissions.

But the sequence, pace, and mechanisms for delivering these goals will vary widely—shaped by each country’s starting point, resource endowment, industrial base, institutional capacity, and market structure. Consequently, strategies must be tailored—not just at the national level, but in many cases regionally and locally. What works in Germany may not work in Indonesia or Texas. For policymakers, this means designing systems that are feasible for the specific context, not the conceptually perfect system.

For companies and investors, it means segmenting markets by technology fit, policy maturity, and bankability—and timing bets accordingly. For multilateral actors, it means focusing on alignment where it matters most: industrialization of common technologies, shared standards, finance mechanisms, and interoperable infrastructure.

Learn more about the critical shifts powering the energy transition, the resulting implications, and what this means for businesses, consumers, and policymakers by downloading the full report below.