Introduction

As health systems around the world strive to improve health care value, one of the biggest obstacles they face is the way that individual clinicians and provider organizations are paid for the care they deliver.

Value in health care is generated by delivering better health outcomes for the same, or a lower, cost. Yet, providers have typically been paid for the activities they perform—irrespective of whether those activities deliver value to patients. In many countries, most physicians are still paid according to the traditional fee-for-service model. And even where clinicians are salaried, their employers are reimbursed for the tests and procedures that their salaried clinicians collectively perform, regardless of the outcomes those activities produce.

The problem is not only that activity-based payment models lack incentives for improving health care value but also that they create powerful disincentives for doing so. To cite one dramatic example, an analysis of more than 34,000 in-patient surgical procedures at a major US hospital system found that privately insured surgical patients with one or more complications provided the hospitals with a profit margin that was 330% higher—an additional $39,000 per patient, on average—than the margin from similarly insured patients who had no complications.

To address these disincentives, health systems around the world are experimenting with new value-based payment models. They are paying performance bonuses to reward providers for meeting predefined thresholds for quality care. They are designing bundled payments that reimburse providers for all the activities associated with discrete episodes of care (for example, joint replacement), both to encourage more innovative and cost-effective treatments for the full cycle of care and to hold providers accountable for the ultimate health outcomes delivered to patients. And in some cases, they are paying lump sums that cover all of the expected costs to serve certain patient populations, creating incentives for providers to invest in prevention, early diagnosis, and proactive treatment in order to minimize total costs to the system.

The amount of experimentation and innovation in designing new value-based payment models is impressive. To give just one example, in a recent survey of US health care executives and clinical leaders, respondents reported that, on average, value-based payments constitute about a quarter of their organization’s revenues, and 42% said they believe that value-based payment will eventually become the primary revenue model in US health care.

But it’s fair to say that the results of all this innovation have, so far, been decidedly mixed. Not all value-based payment initiatives have resulted in improvements in health care value, and it is unclear why some programs have worked while others have not. Meanwhile, much of the discussion about value-based payment focuses on the relative merits of various payment models.

When it comes to value-based payment, perhaps the greatest challenge that health systems face today is how to implement value-based payment models at the level of an entire health system. Even when individual payment initiatives demonstrate improved health care value, it is not immediately obvious how to knit them together into a comprehensive and coherent system-wide payment regime. For example, what is the best way to organize payment for a patient with comorbidities who may use multiple parts of the health system—primary and acute care, or elective and emergency procedures—often concurrently? So far, the global health care sector lacks clear, actionable strategies for health systems that want to implement value-based payment models at regional or national levels.

The global health care sector lacks clear strategies for health systems that want to implement value-based payment.

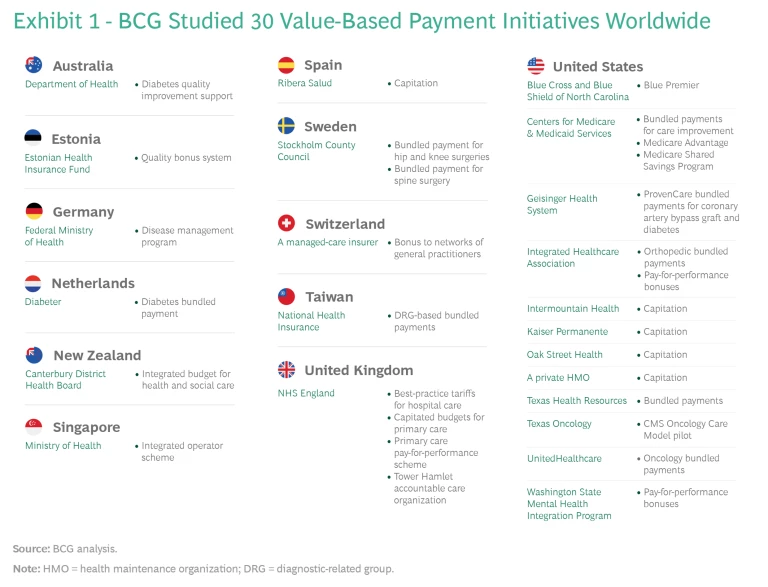

That system-wide level is the focus of this report. During the past year, BCG studied 30 value-based payment initiatives worldwide and reviewed the growing scientific literature about payment models. We looked at programs initiated by public and private payers covering single provider organizations and multiple organizations, and by governments that are leaders in value-based health care as well as others that are just beginning to focus on value. (For a list of initiatives studied, see Exhibit 1.)

In addition to creating a clear and consistent taxonomy of value-based payment models, we identified best practices both within and across models and analyzed how various models can be linked together into a coherent system-wide design. Our research led to three high-level conclusions:

- Value-based payment isn’t an end in and of itself but, rather, a means to an end: creating a new organizational context in which improving health care value becomes a rational behavior for all stakeholders.

- When it comes to changing behavior, financial incentives matter—but so do organizational cultures, norms, practices, and data and analytics. Therefore, it is critical not to conceive of value-based payment in isolation but, instead, to see it as just one element in a broad system transformation that will require considerable investment and long-term institutional commitment. If initiatives are conceived narrowly as a way to achieve immediate short-term cost-savings, they are likely to fail.

- No single value-based payment model is appropriate for all situations or all patient groups; rather, the challenge is to choose the right type of model for a given situation or patient group and to link different models together into a comprehensive value-based payment system.

In this report, we review the existing value-based payment models and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each. We then identify seven characteristics of successful value-based payment initiatives. We also propose three pragmatic interventions that leaders can use today to build coherent value-based payment systems—regardless of their organizations’ starting points or existing capabilities. Finally, we discuss some common system challenges that leaders will encounter.

Varieties of Value-Based Payment

Most health care providers want to do the best for their patients. But, too often, traditional activity-based payment models create disincentives to engage in the kind of clinical behaviors that improve health care value. The purpose of value-based payment is to eliminate these obstacles and create financial incentives to encourage provider behaviors that improve the value delivered to patients. (See the sidebar “Five Provider Behaviors That Boost Health Care Value.”)

Five Provider Behaviors That Boost Health Care Value

Five Provider Behaviors That Boost Health Care Value

In recent years, a growing consensus has emerged among health care leaders about the specific provider behaviors that reinforce health care value.4 Five behavioral imperatives are especially important:

- Engage patients so that they play a more active role in the choices and decisions that shape their health.

- Prioritize wellness and disease prevention in order to maximize overall population health and minimize total health-system costs.

- Deliver high-quality, appropriate treatment, with an emphasis on early intervention in order to shift care upstream to lower cost points on the care-delivery pathway.

- Embrace continuous improvement and clinical innovation in care delivery through increased collaboration across the health system and sharing of best practices.

- Do all this while also managing the total costs of the system.

(For an illustration of these behaviors, see the exhibit below.)

The precise form that these behaviors take will vary by patient group. With relatively healthy patients, for instance, the primary emphasis will be on getting individuals to take responsibility for their own health and making healthy lifestyle choices. That means supplementing traditional medical interventions (vaccinations, routine screenings, and the like) with broader behavioral and socioeconomic interventions that can have a major impact on an individual’s health. Examples include increasing awareness about the importance of diet and nutrition and regular exercise as well as addressing such issues as lack of food security and homelessness.5

For the chronically ill, the emphasis will be on early detection and intervention in order to slow disease progression, avoid the development of acute complications and comorbidities, and also minimize the long-term costs of treatment. Early detection and intervention are critical because they are perhaps the most important drivers of cost containment in today’s health systems. A key focus for this patient group is for primary care providers to direct patients to the relevant specialists and work closely with them to ensure holistic disease management across the full cycle of care.

For patients facing an acute illness or condition, a top priority will be to take time to understand the specific health outcomes that matter to patients in any individual case, so that those preferences are factored into treatment choices. Providers also need to adopt a team-based approach to care that is characterized by increased collaboration with other providers in inpatient specialties, such as surgery and oncology, as well as experts in rehabilitation and community and social care.

Across all patient groups, these activities need to be pursued in an environment of continuous improvement in which providers are encouraged to identify and adopt innovations in care delivery—for example, the routine tracking and analysis of health outcomes by patient group and the regular sharing of best practices with colleagues and peers.

Finally, providers need to do all this while also paying close attention to managing the total costs of the health system. In an environment characterized by limited budgets, every dollar wasted is a dollar that cannot be spent on innovations that improve the health outcomes delivered to patients. Therefore, it is critical for a value-based health system to create mechanisms to improve the allocation of scarce resources so that they generate the most impact.

Notes

4. For more on the behavioral dimension of value-based health care, see Stefan Larsson and Peter Tollman, “Health Care’s Value Problem—and How to Fix It,” BCG article, October 23, 2017, and Value in Healthcare: Mobilizing Cooperation for Health System Transformation, World Economic Forum Insight Report, January 2018.

5. For an excellent discussion of the critical importance of social and behavioral determinants of health, see Robert M. Kaplan, More Than Medicine: The Broken Promise of American Health (Harvard University Press, 2019).

In the past, most health systems have relied on a typical division of labor. Payers were responsible for managing the costs to health systems, while providers were responsible for the quality of care delivered to patients (although often lacking the information to effectively measure it). A core principle of value-based health care is that payers and providers should share accountability for and jointly manage costs and quality. Payers have a key role to play because they have visibility across health systems and, therefore, are well positioned to monitor outcomes and costs for full cycles of care. However, providers are on the frontline of care delivery making the day-to-day decisions that affect patient care. Therefore, they are in the best position not only to make informed tradeoffs about how best to deliver quality care in the most cost-effective way but also to innovate clinically to transcend those tradeoffs and deliver the same or better quality at a lower cost. Three value-based payment models—pay-for-performance bonuses, bundled payments, and population-based payments—help create incentives for providers to achieve these goals.

Pay-for-Performance Bonuses

The simplest form of value-based payment is to pay a bonus to providers when they achieve a predetermined performance goal—for example, when they meet a defined threshold for quality care, effectively manage costs, follow clinical guidelines, or track and report health outcomes.

Bonuses can be used to introduce a value-based component to a traditional fee-for-service payment system. They can be used in combination with other value-based payment models. They can be designed as a pure upside incentive to base compensation in order to limit provider risk, or some portion of that base compensation can be put at risk if providers do not achieve their performance targets.

More and more evidence suggests that small but meaningful financial bonuses can influence provider behavior in ways that improve quality.

Small but meaningful bonuses can influence provider behavior in ways that improve quality.

Less common, however, is the use of pay-for-performance bonuses to reward providers for managing the total cost of care. One recent approach is the shared savings model used at many accountable care organizations (ACOs). ACOs emerged in the US as a result of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which took effect in 2010.

The early results have been mixed. ACOs that participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) of the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) typically outperform non-ACO providers on the quality measures tracked by CMS.

The jury is still out as to whether the ACO model, developed in the context of the US health insurance system, is relevant to other national health systems.

Using a Bonus to Manage Total Cost and Quality

Using a Bonus to Manage Total Cost and Quality

The Swiss General-Practitioner Networks

In Switzerland, most providers are paid on a fee-for-service basis, and most patients can freely choose which providers they use for their health care. In recent years, however, a variety of managed-care options have been introduced into the national health system. One such managed-care model brings primary care providers (known as general practitioners, or GPs) together in networks that manage the total cost and quality of the care delivered to their aggregate patient population. GPs receive a base compensation that is a combination of a per-patient subscription fee and fee-for-service payments. But GPs have the potential to earn a bonus when their network’s quality-of-care score is above a predefined threshold and the total cost of care for the pooled patient population is below risk-adjusted expectations.

The design of the bonus in the Swiss GP networks has some distinctive characteristics. First, the bonus rewards improved performance in two areas: quality and cost. Second, it is relatively modest: a maximum of 10% of base compensation—big enough to focus providers’ attention on optimizing the quality and cost impacts of their decisions but not so big that it encourages providers to game the system. Third, the bonus has only an upside; providers have no downside risk. This approach was taken to build trust between payers and providers and to encourage providers to opt in to the voluntary network model. Fourth, the program defines quality by a few simple metrics that are tracked through a routine patient survey. Meanwhile, the program uses predictive analytics to estimate the total costs for the aggregated patient population on the basis of demographic data, diagnostic categories, and other information. Finally, the bonus is collective, calculated for the network as a whole and shared equally among the doctors in the network, to avoid intrateam competition and to encourage collaboration and best-practice sharing.

Just as important as the design of the bonus are a series of parallel nonfinancial features of the GP network model. For example, GPs play a gatekeeper role in the model, responsible for referring patients to specialists for care. As a result, GPs have the power to manage the total costs of the system on which their bonuses partly depend through referrals to high-value specialists.

What’s more, payers share extensive data on quality and costs with the teams. This data includes the performance of individual GPs, compared with their peers, and the performance of the local hospitals and specialist clinics to which the GPs refer their patients. GPs also participate in weekly quality circles, facilitated by the payer, to share knowledge and best practices.

The combination of the modest bonus, gatekeeper role, and data-driven approach to continuous improvement has led to a variety of beneficial effects: more focus on prevention, especially for chronic conditions; more attention to patient preferences; more cooperation and teamwork between primary and secondary care providers; and increased referrals to the hospitals and specialists that provide the best care in the most cost-effective manner. The program has also led GPs to embrace some simple but powerful changes, such as extending their clinic hours to reduce unnecessary visits to emergency rooms and hospitals, which have more expensive services.

These changes have had a significant impact on the total costs of the system. An internal study found that the Swiss primary-care networks reduced their costs by 17%, compared with a control group, while maintaining the overall quality of care.

Bundled Payments

Another model that health systems are implementing to shift the focus to health care value is to establish a comprehensive fee for a clearly defined episode of care, rather than paying providers for each discrete service delivered in the care cycle. Known as bundled payments, this model also typically makes a portion of provider compensation conditional on the ultimate health outcomes of patients well after the initial surgery or treatment. This creates incentives for providers to factor in the downstream effect of their clinical decisions, strive to minimize complications and avoid medically unnecessary care, and make informed tradeoffs (such as whether to recommend expensive hospitalization or cost-effective outpatient care) at various points in the care cycle.

As health systems gain experience with bundled payments, they are developing increasingly sophisticated ways of designing and implementing them and spreading them across the entire health system. In Sweden, for example, a single pilot project that started in the Stockholm metropolitan area has spread to other regions over the past decade and, in some situations, delivered double-digit improvements in both health outcomes and costs. (See the sidebar “Sweden’s Expanding Program of Bundled Payments.”)

Sweden’s Expanding Program of Bundled Payments

Sweden’s Expanding Program of Bundled Payments

Sweden’s national health system is systematically expanding bundled payments. In 2009, the Stockholm County Council (the public entity responsible for funding health care for the roughly 2 million residents of the greater Stockholm metropolitan area and commonly known by its Swedish acronym, SLL) piloted a bundled payment program for cataract surgery and hip and knee replacement.14

This early initiative had a relatively simple design. For example, in order to minimize the need for risk adjustment, the hip-and-knee-replacement bundle was limited to a focused group of patients: those without comorbidities that caused functional impairment. The bundle sets a single base price that covers the entire care-delivery value chain, including diagnostics, the cost of the implant, surgery, postoperative care, rehabilitation, and follow-up visits. Patients choose either public or private providers in the region on the basis of publicly available information about waiting times, quality metrics, and health outcomes, all posted on the SLL website. Providers are responsible for all complications up to two years after surgery, including all diagnostics and any nonacute complications related to the primary surgery. For each calendar year, providers also receive either a bonus or a penalty of up to 3% of the total bundled-payment reimbursement for the year. The bonus or penalty is based on whether providers meet defined thresholds for reporting health outcomes and for delivering specific outcomes to patients.

The new payment model has been the catalyst for a shift in patient volumes from acute-care hospitals to less expensive specialty clinics. It has also led to process improvements in hospitals that have resulted in fewer physician visits per case, hospitalizations, and inpatient days. Most important, the introduction of the hip-and-knee-replacement bundled payment has had a major positive impact on both health outcomes and costs. In the first two years of the program, complications decreased by 18%, reoperations by 23%, and revisions by 19%. What’s more, costs per patient declined by 14% in terms of resources used by providers and 20% in terms of money paid out by SLL.

In 2013, the success of the hip-and-knee-replacement bundle led SLL to introduce a parallel bundle for spine surgery at the three clinics that provide 70% of all spine care in Stockholm County. Given the variety of diagnoses and types of spine surgery, the design of the spine surgery bundle is considerably more complex. Working in collaboration with the Swedish Society of Spinal Surgeons and the Swedish digital health company Ivbar, SLL developed a system in which, unlike the joint replacement bundle, the price of the spine bundle varies depending on the specific diagnosis and risk profile of the patient. The system uses advanced analytics and predictive models to set the precise reimbursement level for an individual patient on the basis of the patient’s medical history and diagnosis, socio-demographic profile, historical costs per patient, and other factors.

Like the joint replacement bundle, the spine bundle includes a warranty of up to two years, depending on the type of complication under consideration. But a larger portion of the total reimbursement is based on the ultimate health outcomes and includes both upside and downside risk. Initially, a 10% bonus on top of the base price is paid out prospectively for the performance-based component of the bundle. This payment is later adjusted either positively by as much 37% or negatively by as much as 24%, depending on the patient-reported health outcomes relative to average outcomes for the patient group and expected outcomes for the individual patient. Finally, the reporting of health outcomes to Sweden’s National Quality Registry for Spine Surgery is mandatory for participating providers. If a provider does not report outcomes or reports inaccurate outcomes, 50% of the pay-for-performance bonus must be paid back; if patients do not report their patient-reported-outcome measures, the 10% bonus remains unadjusted.

In the three years after the spine surgery bundle was introduced, the total length of stay for lumbar spinal stenosis (representing about 50% of all spinal surgeries) declined by 28% at participating clinics, compared with only 1% at clinics not participating in the program. Reoperation rates declined by 28%, compared with a 44% increase at nonparticipating clinics in Stockholm County and an 18% increase in four other Swedish counties with no bundled payment program during that same period. The average cost per episode decreased by 9%, and the average cost per surgery declined by 7%.

The initial success of the Stockholm County bundled-payment program was a key factor in launching a national program for value-based performance monitoring and payment (known by the Swedish acronym SVEUS). Inaugurated in 2013, the program currently has 40 participating organizations in five regions and counties and provides continuous monitoring of risk-adjusted outcomes and cost data covering 70% of the Swedish population and seven key patient groups: joint replacement, spine surgery, bariatric surgery, birth care, diabetes, stroke, and breast cancer. Currently, the SVEUS analytics platform is being used to calculate bundled payments for spine surgery in the Stockholm region and for spine surgery, bariatric surgery, and hip and knee surgery in the county of Västra Götaland.

Note

14. In January 2019, SLL changed its name to Region Stockholm.

Population-Based Payments

A third value-based payment model pays a predetermined fee to cover all the health needs of each person in a given patient population. The classic example is capitation. Capitation gives providers a powerful financial incentive to manage total system costs. In effect, providers take on the financial risk of delivering cost-effective care. To the degree that they can keep costs under the capitated payment, providers benefit financially; to the degree that they cannot, providers suffer losses (although most capitated systems insure providers against extreme outlier cases). In order to deliver improved health care value, however, capitation must be combined with systematic tracking of health outcomes for specific patient groups or paired with a bonus for delivering high-quality care. This ensures that cost savings are not achieved through rationing or other practices that come at the expense of patient health outcomes.

Capitation has long been in place (often in combination with other forms of value-based payment models, such as bonuses or bundled payments) at US integrated payer-providers, such as Kaiser Permanente and Intermountain Healthcare, both of which are acknowledged as leaders in value-based health care.

Given this complexity, many health systems are experimenting with other ways to focus providers on population-wide quality and costs. One approach is to use proxies for total population quality and costs, such as the ACO shared-savings program discussed above. Another is to create targeted capitation payments for specific population groups (for example, healthy newborns or all patients suffering from diabetes). Capitation is used in New Zealand for primary care, in the UK for mental health, and in the US by Medicare Advantage programs (which are offered to Medicare patients by US private insurers). The latter have been shown to deliver better health outcomes than traditional fee-for-service Medicare programs at nearly one-third the cost.

Characteristics of Successful Payment Initiatives

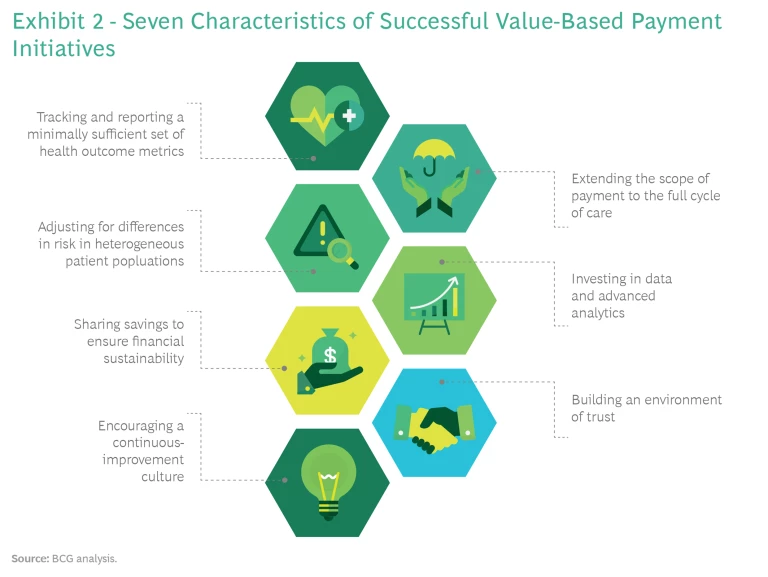

Of the 30 value-based payment initiatives we studied, about half reported quantified improvements in both quality and costs, a quarter reported improvements but without rigorous assessment, and another quarter reported mixed results or no improvement in health care value. When we looked closely at these case studies, we identified seven characteristics that were common to successful value-based payment initiatives—regardless of the payment model—and that distinguished them from the rest. (See Exhibit 2.)

Tracking and Reporting a Minimally Sufficient Set of Health Outcome Metrics

Value-based health care is all about delivering better health outcomes for the same, or a lower, cost. Therefore, measuring and reporting the health outcomes that matter to patients is a prerequisite for achieving sustainable value-based payment reform. The most successful initiatives that we studied supplement their traditional metrics—such as adherence to process standards and compliance with treatment guidelines—with metrics that reflect the health outcomes delivered to patients. Indeed, some of the most successful initiatives include financial incentives for providers to report outcomes; others mandate reporting outcomes as part of a national health policy.

When tracking health outcomes, it’s important to strike the right balance between too many metrics and too few. Too many, and the metrics will provide weak signals that have minimal impact on provider behavior; too few, and they risk missing relevant outcomes.

When tracking health outcomes, it’s important to strike the right balance between too many metrics and too few.

Consider the example of prostate cancer. If a health system tracks only long-term mortality (say, five-year survival rates), then the system is likely to miss large variations in outcomes that matter to patients—for instance, whether or not they suffer from incontinence or severe erectile dysfunction a year after surgery. Organizations such as the International Consortium of Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) have made significant progress in defining minimally sufficient sets of the relevant health outcomes for specific diseases and conditions.

When outcomes tracking and transparency are in place, should a health system link provider compensation to outcomes achieved—for example, in the form of a bonus? Not necessarily. In more market-driven health systems or in systems where value-based health care is in the early stages of development, creating such a link may be effective in jump-starting the behavior changes needed to improve health care value. But there is considerable evidence to suggest that the act of making outcomes transparent can, in and of itself, drive significant improvements in health care value.

Extending the Scope of Payment to the Full Cycle of Care

For many of the initiatives we studied, the effort to improve health care value failed because value-based payments were limited to only a subset of the care required to achieve desired patient outcomes. In such situations, the payment model did not create incentives for providers to innovate across the full chain of care delivery or manage the total cost of care. By contrast, successful initiatives extended the scope of value-based payments to the full cycle of care (for example, expanding payments to include diagnostics, surgery, and physical therapy), so that providers have an incentive to share information, cooperate with one another to redesign care pathways, and provide the highest-quality care in the most cost-effective manner.

Adjusting for Differences in Risk in Heterogeneous Patient Populations

One of the unintended consequences that designers of value-based payment models need to guard against is inadvertantly creating incentives that encourage providers to cherry-pick only the healthiest patients. Effective value-based payment systems include robust risk adjustment in order to account for patient mix, eliminate adverse selection, and set prices that are fair to all providers, including those managing the most complex and expensive-to-treat cases. Although risk adjustment has historically been prohibitively complex, it is now more accurate and easier to implement, given the advances in computing power, the increasing availability of large data sets, and improvements in predictive analytics.

Investing in Data and Advanced Analytics

To meet the growing need for more comprehensive tracking of outcomes and costs, to have value-based payments cover the full cycle of care, and to implement multiple types of payments at scale, successful initiatives develop advanced-analytics platforms. These platforms integrate data from several sources and continuously feed information to all stakeholders on how they are performing on value. Typically, individual providers do not have either the data or the analytics capabilities to develop such systems on their own. In contrast, because payers have visibility across the entire system, they are usually better positioned to develop the data and analytics platform and then provide it as a shared service to providers. Sweden’s SVEUS program, which provides comprehensive and nearly real-time data with sophisticated risk management, is one example of how these analytics platforms are developing.

Sharing Savings to Ensure Financial Sustainability

Another pattern we observed is that, too often, value-based payment models are implemented by payers as a means to reduce costs in the face of immediate budget pressure. Not enough attention is given to the long-term financial sustainability of the programs. Providers may share in the savings in the short term, but those near-term savings then become the justification for budget reductions in subsequent years. When this happens, it is difficult for providers to see a long-term path to success. For example, a chief criticism of the ACO model in the US is that since the cost benchmarks are based on the previous year’s spending, any savings an ACO achieves are immediately factored in to the subsequent year’s benchmark.

An alternative approach was recently announced for the Blue Premier program, a collaboration of Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina (the largest payer in the state) and five major provider systems. Blue Premier has built in mechanisms that protect long-term financial sustainability by ensuring that providers are not penalized in subsequent years for cost improvements in previous years.

Building an Environment of Trust

In order for value-based payment models to drive changes in clinical practice, they need to be introduced in an environment of trust among providers, payers, and patients. That may sound like a tall order given the long history of adversarial relations between payers and providers due to the misaligned incentives of fee-for-service reimbursement models. Still, health systems can take a number of steps to build that trust and ensure sufficient buy-in for value-based payment reform. For example, payers can make clear that the focus of initiatives is not just cost containment but also improvement in outcomes. And providers should be heavily involved in the design, implementation, and refinement of payment models, including defining outcomes and reviewing performance bonus criteria. Furthermore, shadow budgets can be employed for a predefined period of time before the implementation of a new payment model to gather feedback, optimize the approach to risk adjustment and claims management, and increase confidence in and understanding of the payment model to ensure a smooth transition.

Encouraging a Continuous-Improvement Culture

Finally, successful health systems recognize that implementing value-based payments is not a one-time event. Rather, it is part of an ongoing transformation of clinical practice. The successful implementation of value-based payments benefits from a learning mindset in which organizations commit to experimentation, innovation, and continuous improvement over time. Indeed, in some situations, it may even involve eliminating value-based payments when the norms and practices of a genuinely value-based organizational culture are firmly entrenched. (For an example, see the sidebar “Why Geisinger Got Rid of Its Value-Based Bonus.”)

Why Geisinger Got Rid of Its Value-Based Bonus

Why Geisinger Got Rid of Its Value-Based Bonus

Geisinger Health System is a $6.3 billion regional US not-for-profit, integrated, delivery system that has been a pioneer in value-based health care. The organization’s ProvenCare methodology, an evidence-based continuous-improvement cycle for standardizing care pathways, emphasizes strict adherence to clinical best practices and systematic measurement of health outcomes by means of a patient’s electronic health record.

Over the years, Geisinger has experimented with a variety of alternative payment models. For example, the system is well known for its groundbreaking bundled payment program. And in 2002, Geisinger became one of the first provider organizations in the US to tie its physicians’ compensation to performance using a set of quality and efficiency measures.

And yet, in 2016, the company eliminated its pay-for-performance bonus and moved to a pure salary model of physician compensation. The goal of the move was to radically simplify the Geisinger compensation system. “At the end of the day, there’s never any perfect system to incent exactly the right things,” said Jaewon Ryu, Geisinger’s former chief medical officer and recently appointed CEO. “You’re either missing something that should be in the measurement pool or maybe some things in there aren’t exactly the right things.”18

Instead of relying on financial incentives to drive individual provider behavior, Geisinger chose to rely on the system’s strong institutional norms, commitment to outcomes transparency, and intrinsic provider motivation to deliver high-value care.

The Geisinger culture includes mandatory adherence to a social contract that encourages the best patient care, multidisciplinary collaboration, and innovation. Strong norms allow Geisinger to give physicians the autonomy to make complex care decisions without worrying about how each decision will affect their income and to put their individual autonomy to the service of the shared goal of maximizing value delivered to patients.

The Geisinger story demonstrates that nonfinancial norms and culture can be as—if not more—important than financial incentives in encouraging the kind of provider behaviors that are important to value-based health care.

Note

18. See Lola Butcher, “Geisinger Scraps Physician Pay-for-Performance,” Leadership +, Healthcare Financial Management Association, June 9, 2017.

Building a Value-Based Payment System

Although the specific approach will, of course, vary depending on the starting point and organization of a given health system, we recommend that health system leaders begin building a value-based payment system by focusing on three strategic interventions. These include creating incentives to:

- Manage the total cost and quality of the health system, which is critical for encouraging providers to prioritize wellness and disease prevention

- Optimize the value of routine specialist care, which are a predictable and relatively high-cost component of any health system, and

- Optimize the value of complex, acute, inpatient care, which is a major source of fixed costs for any health system

Incentives to Manage Total Cost and Quality

A critical component of payment reform is to create incentives that encourage providers to manage the total cost and quality of care delivered to the patients they serve. When providers have an incentive to take a system perspective on cost and quality, they are more likely to prioritize wellness and prevention for healthy patients and to invest in the ongoing management of complex and costly illnesses for the chronically ill. Providers are also more likely to embrace innovations in care delivery (for example, digital health solutions) that have been demonstrated to have a material impact on cost and quality.

Providers are more likely to embrace innovations when they have an incentive to manage the total cost and quality of care.

Ideally, there should be a single actor in the system that has chief responsibility for managing total cost and quality for a given population of patients. For most patient groups, that will be the primary care provider. Primary care providers are best positioned to encourage wellness and prevention and to intervene early for a chronic disease, managing it over time in order to slow its progression. And when patients require more specialized care, primary care providers are a key interface with the rest of the health system, both in determining when patients need such care and in referring them to the most appropriate specialists. Given their multifaceted role, primary care providers play a central role in influencing the overall costs and quality of the health system. However, for select patient groups suffering from especially severe or complex conditions, it may make more sense for a specialist provider to manage total cost and quality.

Before health systems adopt complex value-based payment models, such as capitation, to manage total cost and quality, we recommend that they introduce simpler models to achieve this goal—for example, the approach taken by the Swiss GP networks.

Incentives to Optimize the Value of Routine Specialist Care

At any moment in time, a subset of a health system’s patients require specialized care. And in every system, certain episodes of care happen frequently and are among the most costly in the system’s budget. Examples include joint replacement, perinatal care, cancer treatment, and certain chronic conditions such as chronic renal failure.

Therefore, a second important intervention should focus on optimizing the cost and quality of these clinical episodes from initial diagnosis through appropriate referral, treatment, and, when possible, recovery. The best approach is to develop bundled payments that cover all the providers in the care pathway for the given clinical episode and create incentives for a collaborative, team-based approach to care. In developing a system-wide approach to bundled payments, it’s best to begin with situations that meet the following criteria:

- The episode of care has a clear profile or a clinically defined start point and end point. Specific inclusion criteria are important to avoid creating an incentive for up-coding and overtreatment (for example, approving a patient for joint replacement who would be better served by physical therapy).

- The care pathway has significant variation in outcomes and costs across patients, and established protocols exist for reducing that variation. Therefore, the episode of care is a promising candidate for improved value through innovation and process redesign.

- Providers are able to control the setting of care and, therefore, influence the care pathway. Some episodes of care, such as trauma care, may be sources of high cost and considerable practice and outcome variation, but the wide variety of patient situations where trauma care is required and the inability of providers to manage the setting of care or standardize the care pathway makes trauma a poor candidate for bundled payments.

- The episode of care represents a significant expense to the health system as a whole (to make it worth the investment of time and effort on the part of payers) and significant volume (to make it worth the investment of providers).

In health systems with multiple payers, a key challenge will be to create common definitions for a given episode. Otherwise, providers will have to adapt to multiple bundled-payment models, adding to system complexity. We believe that there is a great deal that health systems can learn from the leaders in the field. Over time, we expect that the bundled payment model will be standardized for specific clinical episodes and patient groups and adopted by health systems around the world.

Incentives to Optimize the Value of Complex, Acute, Inpatient Care

Whether in a metropolitan area, a region, or across an entire nation, any health system has to fund an extensive fixed-cost infrastructure of hospitals and other facilities to deal with complex cases and acute emergency care. Planning for this infrastructure has two main challenges: estimating the likely needs of the patient population and treating patients in the setting that is best both for patient health and system costs.

Typically, the cost of complex and acute inpatient care has been covered through some combination of activity-based payments and block funding, which is determined on the basis of the hospital’s historical capacity, the size of the population it serves, and its specific role in the health system (for example, an academic medical center with special responsibility to train doctors and innovate experimental types of treatment, or a rural hospital with a mission to deliver acute care in underpopulated regions).

These traditional funding approaches have not typically focused on value. Activity-based payments reimburse hospitals for the procedures performed, rewarding for volume. And population-based or role-based block funding has typically been linked to the number of beds in the facility, rather than a true estimate of the health needs of the population that the hospital serves. Further, traditional payment approaches are rarely tied to patient outcomes, and as a result, are ineffective incentives for value-based care. In fact, they can contribute to a system that relies excessively on expensive hospital care and maintains excess capacity.

With careful design, however, block funding can be transformed into a strategic intervention for building a value-based payment system. First, instead of assigning funding levels by facility size, health systems should employ predictive analytics to estimate likely usage levels on the basis of the demographic, disease, and risk profiles of a region’s population. (Safeguards can also be put in place to protect provider budgets against unusually high costs associated with specialized care that is difficult to predict—for example, major trauma.) A forward-looking rather than historical estimate of demand in critical patient populations can be an effective way to manage capacity; plan for scheduling, training, and clinical education; and adjust to new innovations in care delivery.

Block funding can be transformed into a strategic intervention for building a value-based payment system.

Second, instead of conceiving of block funding as limited to the hospital setting, health systems should extend the scope of such funding to settings across the entire network of care. Taking this step creates an incentive for providers to direct demand to the most appropriate and cost-effective site of care—for example, outpatient clinics, community-care facilities, or in-home care with remote monitoring. In this approach, regional hospitals function less as the main site of care and more as a hub in a network. And hospital-based specialist providers become, in effect, general contractors who are responsible for finding the most cost-effective and highest-quality site of care across the entire value chain, contracting with outpatient facilities and working with specialists—such as discharge nurses, visiting nurses, and home health aides—to minimize the total cost of care. Block funding is the approach taken, for example, by Kaiser Permanente, to fund its infrastructure of 38 hospitals in ten states. (See the sidebar “Strategic Block Funding at Kaiser Permanente.”)

Strategic Block Funding at Kaiser Permanente

Strategic Block Funding at Kaiser Permanente

Kaiser Permanente (KP), an integrated payer-provider with more than 12 million members, is the largest nonprofit health plan in the US. Over the years, KP has created an integrated model of care delivery that promotes collaboration among care providers, emphasizes preventive care and the active management of chronic disease, and includes incentives that simultaneously promote excellent clinical outcomes and resource efficiency. As a result, KP has been able to provide employers with health benefits that are, on average, 10% to 20% more cost-effective than traditional managed-care plans, while delivering outstanding quality.

To achieve these goals, KP uses the full panoply of value-based payment approaches, including population-based capitation and provider bonuses tied to quality of care and system financial performance—all supported by systematic outcomes measurement, sophisticated risk adjustment, and an integrated approach to improving the value delivered to patients across the entire cycle of care. But perhaps the approach that other health systems can most easily adopt is KP’s approach to funding the network’s infrastructure of 38 hospitals in ten states.

The annual budgeting process consists of a bottom-up view of budget requirements developed by each KP hospital and its affiliated providers and a top-down view developed by the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan (KP’s internal health plan) and the regional Permanente Medical Group. The approach uses predictive analytics to evaluate the requirements and to forecast likely usage on the basis of historical data, population trends, and the disease burden of the population the hospital covers. A committee of representatives from the health plan and the hospitals reviews the funding proposal, negotiates any disagreements or disputes, and comes to a consensus around the forthcoming year’s budget. The agreed-upon budget includes the expected use of community care, discharge nurses, and any other outpatient services that minimize costly hospital stays and help achieve desired clinical outcomes. The hospitals handle payment for patients who received treatment outside their home region through transfer pricing.

When a hospital’s total block-funding budget is set, a hospital’s managers and providers have the freedom to determine the best way to allocate the funds in order to achieve the desired patient outcomes. There are quality metrics for the hospital as a whole and for individual providers within the hospital, with quality bonuses awarded to service lines on the basis of a balanced scorecard.

The KP block-funding approach incorporates incentives for high-value care. For example, it has metrics for the shortest appropriate length of stay by condition or disease and a triage system that uses in-home care and outpatient facilities as appropriate to avoid unnecessary admissions. Care pathways are organized to provide effective treatment and to avoid complications or readmission and unnecessary care.

It’s the rare health system that can replicate KP’s entire value-based health system from scratch. But the system’s strategic use of block funding to support its infrastructure is one discrete intervention that can be adopted directly by other health systems that are building value-based payment systems.

Some Common System Challenges

As health systems pursue these interventions, they will also face at least three system-wide challenges. The first is defining the necessary linkages among the payment models. The second is developing measurement systems for tracking health outcomes and costs and building the advanced analytics platform necessary both to feed data to providers and use it as a basis for value-based payments. The third is creating systems to manage risk, both in terms of patient mix and providers’ financial exposure.

In the course of a lifetime, patients will have different needs covered by different value-based payment models. Health system leaders will need to design systems for managing these models across different patient populations and different types of providers. These systems will need to be sufficiently comprehensive but not so complex that they become unmanageable. The principal should be to make the system as simple as possible for patients and providers, while managing complexity through back-end IT systems. Critical choices and tradeoffs will also need to be made around issues such as deciding where to focus a health system’s bundled payment initiatives, how to organize provider payments for patients suffering from multiple morbidities, and what kind of data and advanced-analytics platforms and visualization tools will be necessary to provide the insights necessary to drive continuous improvement of patient value.

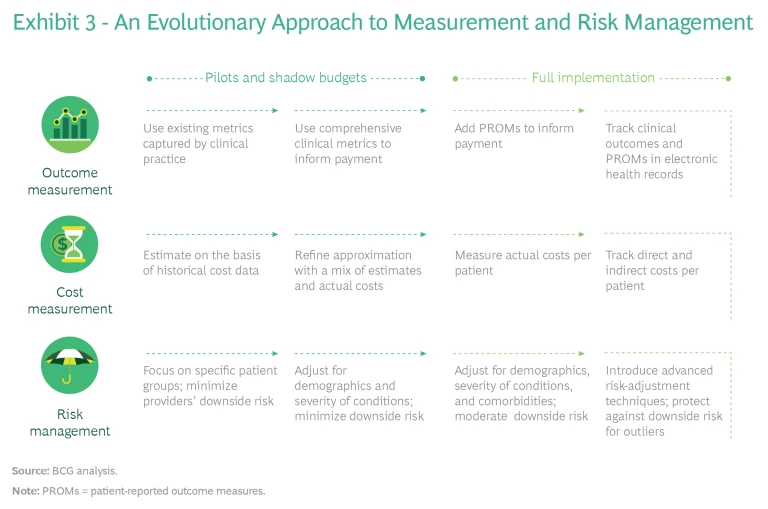

When it comes to measuring outcomes and cost and managing risk, we recommend an evolutionary approach. Health systems don’t have to wait until they have advanced-measurement and risk-adjustment systems in place to get started. Rather, they can begin by using the metrics and methodologies they have, investing in and learning from pilots, and then refining their current systems before implementing payment models system-wide.

For example, to measure health outcomes, start by using existing metrics that are already captured in clinical practice; then, over time, develop advanced information systems in order to routinely capture metrics for both clinical and patient-reported outcomes that are in patients’ electronic health records. To track costs, start with estimates that are based on historical data; then, over time, develop systems that track actual direct and indirect costs per patient. In parallel, start piloting the data and analytics platforms that are necessary to collect the data and share it across the system. To manage risk, initially focus value-based payment models on clearly defined patient groups and exclude downside risk to minimize providers’ financial exposure. Then, over time, gradually introduce more advanced risk-adjustment techniques that allow value-based payment models to be expanded to more complex patient groups (for instance, those with multiple morbidities). And as providers develop the capabilities to manage costs, exclude downside risk only for extreme outlier cases. (See Exhibit 3.)

The appropriate balance between financial and nonfinancial incentives for value-based health care is also likely to evolve over time. In some situations, value-based payments will be the primary catalyst for the long-term reorientation of health systems around value delivered to patients. But as value-based norms and cultures develop in provider organizations, and health systems put in place the analytics to make outcomes and costs transparent, financial incentives may play a less central role.

The point: implementing a value-based payment system is likely to be a dynamic process with considerable experimentation, learning, and adaption. Health system leaders need to be pragmatic and action-oriented. In addition, rather than treat value-based payment in isolation, leaders need to recognize it as one element in a broader set of system-wide changes, designed to align patient, provider, and payer behaviors around the shared goal of improving health care value.